State, Culture, and Avant-Gardism in India (Ca

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Complete List of Books in Library Acc No Author Title of Book Subject Publisher Year R.No

Complete List of Books in Library Acc No Author Title of book Subject Publisher Year R.No. 1 Satkari Mookerjee The Jaina Philosophy of PHIL Bharat Jaina Parisat 8/A1 Non-Absolutism 3 Swami Nikilananda Ramakrishna PER/BIO Rider & Co. 17/B2 4 Selwyn Gurney Champion Readings From World ECO `Watts & Co., London 14/B2 & Dorothy Short Religion 6 Bhupendra Datta Swami Vivekananda PER/BIO Nababharat Pub., 17/A3 Calcutta 7 H.D. Lewis The Principal Upanisads PHIL George Allen & Unwin 8/A1 14 Jawaherlal Nehru Buddhist Texts PHIL Bruno Cassirer 8/A1 15 Bhagwat Saran Women In Rgveda PHIL Nada Kishore & Bros., 8/A1 Benares. 15 Bhagwat Saran Upadhya Women in Rgveda LIT 9/B1 16 A.P. Karmarkar The Religions of India PHIL Mira Publishing Lonavla 8/A1 House 17 Shri Krishna Menon Atma-Darshan PHIL Sri Vidya Samiti 8/A1 Atmananda 20 Henri de Lubac S.J. Aspects of Budhism PHIL sheed & ward 8/A1 21 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad Bhagabatam PHIL Dhirendra Nath Bose 8/A2 22 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam VolI 23 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam Vo.l III 24 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad Bhagabatam PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 25 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam Vol.V 26 Mahadev Desai The Gospel of Selfless G/REL Navijvan Press 14/B2 Action 28 Shankar Shankar's Children Art FIC/NOV Yamuna Shankar 2/A2 Number Volume 28 29 Nil The Adyar Library Bulletin LIT The Adyar Library and 9/B2 Research Centre 30 Fraser & Edwards Life And Teaching of PER/BIO Christian Literature 17/A3 Tukaram Society for India 40 Monier Williams Hinduism PHIL Susil Gupta (India) Ltd. -

FINAL COMBINED SENIORITY LIST of Asis (DISTRICT and PAP) AS PER CONFIRMATION

FINAL COMBINED SENIORITY LIST OF ASIs (DISTRICT AND PAP) AS PER CONFIRMATION Sr No. RANK, NAME & NO/ RANGE DOB DOE CASTE/ LIST C-I LIST C-II ACTUAL LIST D-I LIST D-II MERIT ACTUAL DATE OF ACTUAL DATE OF DATE OF DOP AS S.I REMARKS CATEGORY DOP AS HC NO. AS DOP AS ASI CONF AS CONF DATE LIST E LIST E-II (ACTUAL) P/ASI ASI OF ASI 1 DALBIR SINGH, 292/J BR 13-10-1944 14-06-1963 GC 20-08-1968 01-01-1971 01-09-1980 13-05-1982 01-01-1987 01-01-1987 01-04-1989 16-04-1992 RETD ON 31/10/2002 2 MOHINDER SINGH, 233/PR CP-LDH 29-10-1948 07-11-1969 SC 28-04-1973 19-11-1974 01-04-1982 27-11-1982 01-07-1988 01-07-1988 01-04-1989 14-05-1992 Retd/ on 31/10/06 3 SWARN DASS, 111/PR, 2/R PR 10-04-1951 29-07-1971 SC 02-11-1976 10-11-1976 27-11-1982 01-07-1988 01-07-1988 01-04-1989 14-05-1992 RETD ON 30/04/2009 4 DSP BALDEV SINGH 35/BR BR 16-03-1957 20-02-1976 JAT SIKH 18-12-1981 06-10-1986 05-10-1988 05-10-1988 01-01-1993 19-04-1993 5 SI MOHINDER SINGH 97/FR FR 11-12-1941 12-12-1960 RAMGARIHA 11-03-1971 05-06-1974 01-09-1983 10-11-1984 01-04-1989 06-09-1990 01-04-1991 20-03-1992 RETD ON 31.12.99 6 INSP PRITPAL SINGH PR/CP- 23-02-1964 09-04-1986 - - - - P/ASI 09-04-1986 21-04-1989 21-04-1989 01-10-1990 18-06-1991 266/PR LDH 7 RETD SI BAKHSHISH SINGH JR 01-12-1940 27-11-1962 GC 09-10-1968 02-05-1971 01-04-1982 09-01-1983 01-07-1989 01-07-1989 01-10-1991 28-04-1992 Died on 30.01.94 38/GSP 380/J 8 Insp Ram Singh NO. -

How Modern India Reinvented Classical Dance

ESSAY espite considerable material progress, they have had to dispense with many aspects of the the world still views India as an glorious tradition that had been built up over several ancient land steeped in spirituality, centuries. The arrival of the Western proscenium stage with a culture that stretches back to in India and the setting up of modern auditoria altered a hoary, unfathomable past. Indians, the landscape of the performing arts so radically that too, subscribe to this glorification of all forms had to revamp their presentation protocols to its timelessness and have been encouraged, especially survive. The stone or tiled floor of temples and palaces Din the last few years, to take an obsessive pride in this was, for instance, replaced by the wooden floor of tryst with eternity. Thus, we can hardly be faulted in the proscenium stage, and those that had an element subscribing to very marketable propositions, like the of cushioning gave an ‘extra bounce’, which dancers one that claims our classical dance forms represent learnt to utilise. Dancers also had to reorient their steps an unbroken tradition for several millennia and all of and postures as their audience was no more seated all them go back to the venerable sage, Bharata Muni, who around them, as in temples or palaces of the past, but in composed Natyashastra. No one, however, is sure when front, in much larger numbers than ever before. Similarly, he lived or wrote this treatise on dance and theatre. while microphones and better acoustics management, Estimates range from 500 BC to 500 AD, which is a coupled with new lighting technologies, did help rather long stretch of time, though pragmatists often classical music and dance a lot, they also demanded re- settle for a shorter time band, 200 BC to 200 AD. -

NAVJOT ALTAF Selected Biography

1260 Carillion Point nyb@nybgallery Kirkland, WA 98033, USA +1 425 466 1776 NAVJOT ALTAF Selected biography From Meerut, India. Education Fine and Applied Arts, Sir J.J. School of Arts, Mumbai, India Graphics, Garhi Studios, New Delhi, India Solo Exhibitions 2018 Lost Text, The Guild Gallery, Alibaug, India. Lost Text, Special Project, Art Fair, New Delhi, The Guild Gallery, India. 2016 How Perfect Perfection Can Be Installation with drawings, sculptures, soil, rice grain, and video, Chemould Prescott Road Art Gallery, Mumbai, India. Catalogue. 2015 How Perfect Perfection Can Be Installation with drawings, sculptures, soil, rice grain, and video, The Guild Gallery Alibaug, India. 2013 Horn in the Head, Sculpture Installation with audio and video, Talwar Gallery, New Delhi, India. 2010 TOUCH IV22 monitors video installation, Talwar Gallery, New Delhi, The Guild, Bombay, India. A place in NY, Photomontage, The Guild Gallery, Bombay and NY, USA. Catalogue. 2009 Lacuna in Testimony - Patricia and Phillip Frost Art Museum, Florida, USA. 2008 Touch 4 projection video installation and interactive sculptures, Sakshi Gallery, Bombay, India. Bombay Shots- Photomontage, The Guild Gallery, Bombay, India. Catalogue. 2006 Jagar Multimedia Installation, and Water Weaving, video Installation, Sakshi Gallery, Bombay, India. Junctions 1 – 2 – 3 Photo installation with sound, The Guild Gallery, Bombay, India. Catalogue. 2005 Water Weaving, Video Installation, Talwar Gallery, NY, USA. Catalogue. 2004 Bombay Meri Jaan and 'Lacuna in Testimony', video Installation, Sakshi Gallery, Bombay, India. Catalogue. 2003 In Response To, sculpture installation with photographs by Ravi Agarwal, Talwar Gallery, NY, USA. Catalogue. Displaced Self, Interactive project with artists from Israel and Ireland, Sakshi gallery, Bombay, India. -

New Regn.Pdf

LIST OF NEWLY REGISTERED DEALERS FOR THE PERIOD FROM 01-DECEMBER-08 TO 16-DECEMBER-08 CHARGE NAME VAT NO. CST NO. TRADE NAME ADDRESS ALIPUR 19604024078 19604024272 BAHAR COMMODEAL PVT. LTD. 16 BELVEDRE ROAD KOLKATA 700027 19604028055 MAHAVIR LOGISTICS 541/B, BLOCK 'N NW ALIPORE KOLKATA 700053 19604027085 P. S. ENTERPRISE 100 DIAMOND HARBOUR ROAD KOLKATA 700023 19604031062 19604031256 PULKIT HOLDINGS PVT. LTD. 16F JUDGES COURT ROAD KOLKATA 700027 19604030092 19604030286 R. S. INDUSTRIES (INDIA) 26E, TURF ROAD KALIGHAT 700025 19604026018 19604026212 RAJ LAXMI JEWELLERS 49/1 CIRCULAR GARDEN ROAD KOLKATA 700023 19604025048 19604025242 SAPNA HERBALS & COSMETICS PVT. LTD. 12/5 MOMINPUR ROAD KOLKATA 700023 19604029025 19604029219 SOOKERATING TEA ESTATE PVT. LTD. P-115, BLOCK-F NEW ALIPORE KOLKATA 700053 19604023011 SURFRAJ & CO. F-79 GARDENREACH ROAD KOLKATA 700024 ARMENIAN STREET 19521285018 19521285212 M/S. TEXPERTS INDIA PRIVATE LIMITED, 21, ROOPCHAND ROY STREET, 3RD FLOOR, KOLKATA 700007 19521286085 19521286279 TIRUPATI ENTERPRISES IST FLOOR, 153, RABINDRA SARANI, KOLKATA 700007 ASANSOL 19747189094 ARCHANA PEARLS 8, ELITE PLAZA G.C. MITRA ROAD ASANSOL 713301 19747194041 ASANSOL REFRIGERATOR MART 46 G.T. ROAD, DURGA MARKET, GIRIJA MOR ASANSOL 713301 19747182013 AUTO GARAGE FARI ROAD BARAKAR, ASANSOL 713324 19747178036 BADAL RUIDAS VIA- ASANSOL KALLA VILLAGE, RUIDAS PAR KALLA (C.H) 713340 19747175029 19747175223 BALBIR ENTERPRISES STATION ROAD BARAKAR 713324 19747179006 19747179297 BAZAR 24 24 G.T. ROAD (WEST) RANIGANJ SEARSOL RAJBARI 713358 -

Advances in Molecular Electronics: a Brief Review

Open Access Global Journal of Arts and Social Sciences Volume 2 Issue 1 ISSN: 2694-3832 Review Article Twentieth Century Bengali Society through Gaganendranath Tagore’s Cartoons Mondal D* English Literature, Visva-Bharati University, Santiniketan, West-Bengal, India Article Info Abstract Article History: Gaganendranath Tagore is known as the first cartoonist in early twentieth century colonial India. His Received: 05 May, 2020 cartoons were markedly different from the ones that preceded him. He brought about a distinct Accepted: 07 May, 2020 modernity with his play of light and shade, depth and volume in his cartoons, something that is Published: 12 May, 2020 comparable with the trends that were popular in Europe then. This is not all. To give a professional edge *Corresponding author: Mondal D, to his cartoons, Gaganendranath started using the lithograph for printing them. Inspired by this trend of M.A., English Literature, Visva- printing them. This genre of drawing has not been highlighted enough, though they have been Bharati University, Santiniketan, instrumental in creating political rhetoric for long. However, the works by Gaganendranath were West-Bengal, India; DOI: neglected. May be for he was ahead of his time, his works were mostly experimental. He took up https://doi.org/10.36266/GJASS/120 caricature to satirize the westernized middle class of urban Bengal. The rise of nationalist sentiment and Swadeshi movement had also influenced his cartoons. This paper will try to look back and analyze the social condition of Bengal through Gaganendranath’s caricatures. Keywords: Caricature; Babu; Satire; Art Copyright: © 2020 Mondal D. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. -

Syllabus of Arts Education

SYLLABUS OF ARTS EDUCATION 2008 National Council of Educational Research and Training Sri Aurobindo Marg, New Delhi - 110016 Contents Introduction Primary • Objectives • Content and Methods • Assessment Visual arts • Upper Primary • Secondary • Higher Secondary Theatre • Upper Primary • Secondary • Higher Secondary Music • Upper Primary • Secondary • Higher Secondary Dance • Upper Primary • Secondary • Higher Secondary Heritage Crafts • Higher Secondary Graphic Design • Higher Secondary Introduction The need to integrate art s education in the formal schooling of our students now requires urgent attention if we are to retain our unique cultural identity in all its diversity and richness. For decades now, the need to integrate arts in the education system has been repeatedly debated, discussed and recommended and yet, today we stand at a point in time when we face the danger of lo osing our unique cultural identity. One of the reasons for this is the growing distance between the arts and the people at large. Far from encouraging the pursuit of arts, our education system has steadily discouraged young students and creative minds from taking to the arts or at best, permits them to consider the arts to be ‘useful hobbies’ and ‘leisure activities’. Arts are therefore, tools for enhancing the prestige of the school on occasions like Independence Day, Founder’s Day, Annual Day or during an inspection of the school’s progress and working etc. Before or after that, the arts are abandoned for the better part of a child’s school life and the student is herded towards subjects that are perceived as being more worthy of attention. General awareness of the arts is also ebbing steadily among not just students, but their guardians, teachers and even among policy makers and educationalists. -

Odisha Review

ODISHA REVIEW VOL. LXXI NO. 2-3 SEPTEMBER-OCTOBER - 2014 MADHUSUDAN PADHI, I.A.S. Commissioner-cum-Secretary BHAGABAN NANDA, O.A.S, ( SAG) Special Secretary DR. LENIN MOHANTY Editor Editorial Assistance Production Assistance Bibhu Chandra Mishra Debasis Pattnaik Bikram Maharana Sadhana Mishra Cover Design & Illustration D.T.P. & Design Manas Ranjan Nayak Hemanta Kumar Sahoo Photo Raju Singh Manoranjan Mohanty The Odisha Review aims at disseminating knowledge and information concerning Odisha’s socio-economic development, art and culture. Views, records, statistics and information published in the Odisha Review are not necessarily those of the Government of Odisha. Published by Information & Public Relations Department, Government of Odisha, Bhubaneswar - 751001 and Printed at Odisha Government Press, Cuttack - 753010. For subscription and trade inquiry, please contact : Manager, Publications, Information & Public Relations Department, Loksampark Bhawan, Bhubaneswar - 751001. Five Rupees / Copy E-mail : [email protected] Visit : http://odisha.gov.in Contact : 9937057528(M) CONTENTS Nabakalebar Bhagaban Mahapatra ... 1 Good Governance ... 5 The Concept of Sakti and Its Appearance in Odisha Sanjaya Kumar Mahapatra ... 8 Siva and Shakti Cult in Parlakhemundi : Some Reflections Dr. N.P. Panigrahi ... 11 Durga Temple at Ambapara : A Study on Art and Architecture Dr. Ratnakar Mohapatra ... 20 Perspective of a Teacher as Nation Builder Dr. Manoranjan Pradhan ... 22 A Macroscopic View of Indian Education System Lopamudra Pradhan ... 27 Abhaya Kumar Panda The Immortal Star of Suando Parikshit Mishra ... 42 Consumer is the King Under the Consumer Protection Law Prof. Hrudaya Ballav Das ... 45 Paradigm of Socio-Economic-Cultural Notion in Colonial Odisha : Contemplation of Gopabandhu Das Snigdha Acharya ... 48 Raghunath Panigrahy : The Genius Bhaskar Parichha .. -

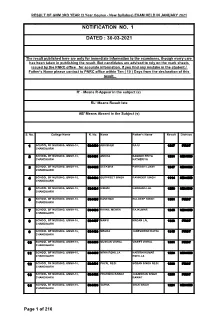

Notification No. 1 Dated : 30-03-2021

RESULT OF GNM 3RD YEAR (3 Year Course - New Syllabus) EXAM HELD IN JANUARY 2021 NOTIFICATION NO. 1 DATED : 30-03-2021 The result published here are only for immediate information to the examinees, though every care has been taken in publishing the result. But candidates are advised to rely on the mark sheets issued by the PNRC office for accurate information. If you find any mistake in the student / Father's Name please contact to PNRC office within Ten ( 10 ) Days from the declaration of this result. R' - Means R-Appear in the subject (s) RL' Means Result late AB' Means Absent in the Subject (s) S. No. College Name R. No. Name Father's Name Result Division 1 SCHOOL OF NURSING, GMSH-16, 534480 ABHISHEK RAJU 1287 FIRST CHANDIGARH 2 SCHOOL OF NURSING, GMSH-16, 534481 ANKITA BAUDDH PRIYA 1231 SECOND CHANDIGARH KATHERIYA 3 SCHOOL OF NURSING, GMSH-16, 534482 DEEKSHA PARKASH LUXMI 1247 SECOND CHANDIGARH 4 SCHOOL OF NURSING, GMSH-16, 534483 GURPREET SINGH RAVINDER SINGH 1114 SECOND CHANDIGARH 5 SCHOOL OF NURSING, GMSH-16, 534484 HIMANI HARBANS LAL 1250 SECOND CHANDIGARH 6 SCHOOL OF NURSING, GMSH-16, 534485 KANCHAN KULDEEP SINGH 1381 FIRST CHANDIGARH 7 SCHOOL OF NURSING, GMSH-16, 534486 KHANIL MEHRA RAJKUMAR 1245 SECOND CHANDIGARH 8 SCHOOL OF NURSING, GMSH-16, 534487 MANSI MADAN LAL 1338 FIRST CHANDIGARH 9 SCHOOL OF NURSING, GMSH-16, 534488 MEGHA JANESHWAR DAYAL 1315 FIRST CHANDIGARH 10 SCHOOL OF NURSING, GMSH-16, 534489 MUSKAN VISHAL VINEET VISHAL 1301 FIRST CHANDIGARH 11 SCHOOL OF NURSING, GMSH-16, 534490 NEHA ROHILLA NARESH KUMAR 1223 SECOND CHANDIGARH ROHILLA 12 SCHOOL OF NURSING, GMSH-16, 534491 PAYAL NEGI SOBAN SINGH NEGI 1296 FIRST CHANDIGARH 13 SCHOOL OF NURSING, GMSH-16, 534492 PRATIBHA RAWAT JAGMOHAN SINGH 1266 FIRST CHANDIGARH RAWAT 14 SCHOOL OF NURSING, GMSH-16, 534493 SAPNA SHER SINGH 1221 SECOND CHANDIGARH Page 1 of 216 RESULT OF GNM 3RD YEAR (3 Year Course - New Syllabus) EXAM HELD IN JANUARY 2021 S. -

Training Module History and Environment

Training Module History and Environment Class X Planning and Development Expert Committee School Education Department West Bengal Board of School Education Department, Secondary Education Govt. of West Bengal Samagra Shiksha Abhiyan Printed at West Bengal Text Book Corporation Limited (Government of West Bengal Enterprise) Kolkata- 700 056 Training Module History and Environment Class X Planning and Development Expert Committee School Education Department West Bengal Board of School Education Department, Secondary Education Govt. of West Bengal Department of School Education, Government of West Bengal Bikash Bhavan, Kolkata- 700 091 West Bengal Board of Secondary Education 77/2, Park street, Kolkata- 700 016 Neither this book nor any keys, hints, comment, note, meaning, connotations, annotations, answers and solutions by way of questions and answers or otherwise should be printed, published or sold without the prior approval in writing of the Director of School Education, West Bengal. Any person infringing this condition shall be liable to penalty under the West Bengal Nationalised Text Books Act, 1977. July, 2020 The Teachers’ Training Programme under SSA will be conducted according to this module that has been developed by the Expert Committee on School Education and approved by the WBBSE. Printed at West Bengal Text Book Corporation Limited (Government of West Bengal Enterprise) Kolkata- 700 056 From the Board In 2011 the Honourable Chief Minister Smt. Mamata Banerjee constituted the Expert Committee on School Education of West Bengal. The Committee was entrusted upon to develop the curricula, syllabi and textbooks at the school level of West Bengal. The Committee therefore had developed school textbooks from Pre-Primary level, Class I to Class VIII based on the recommendations of National Curriculum Framework (NCF) 2005 and Right to Education (RTE) Act 2009. -

Result of Gnm 1St Year Exam Held in December - 2018

RESULT OF GNM 1ST YEAR EXAM HELD IN DECEMBER - 2018 NOTIFICATION NO. 1 DATED : 31-05-2019 The result published here are only for immediate information to the examinees, though every care has been taken in publishing the result. But candidates are advised to rely on the mark sheets issued by the PNRC office for accurate information. If you find any mistake in the student / Father's Name please contact to PNRC office within Ten ( 10 ) Days from the declaration of this result. R' - Means R-Appear in the subject,(s) RL' Means Result late AB' Means Absent S. College Name Roll No Name Father Name Result No. 1 SCHOOL OF NURSING, GMSH-16, 483001 ABHISHEK RAJU 354 CHANDIGARH 2 SCHOOL OF NURSING, GMSH-16, 483002 ANKITA BAUDDH PRIYA 315 CHANDIGARH KATHERIYA 3 SCHOOL OF NURSING, GMSH-16, 483003 DEEKSHA PARKASH LUXMI 334 CHANDIGARH 4 SCHOOL OF NURSING, GMSH-16, 483004 GURPREET SINGH RAVINDER SINGH 312 CHANDIGARH 5 SCHOOL OF NURSING, GMSH-16, 483005 HIMANI HARBANS LAL 332 CHANDIGARH 6 SCHOOL OF NURSING, GMSH-16, 483006 KANCHAN KULDEEP SINGH 366 CHANDIGARH 7 SCHOOL OF NURSING, GMSH-16, 483007 KHANIL MEHRA RAJKUMAR 328 CHANDIGARH 8 SCHOOL OF NURSING, GMSH-16, 483008 MANSI MADAN LAL 356 CHANDIGARH 9 SCHOOL OF NURSING, GMSH-16, 483009 MEGHA JANESHWAR DAYAL 347 CHANDIGARH 10 SCHOOL OF NURSING, GMSH-16, 483010 MUSKAN VISHAL VINEET VISHAL 355 CHANDIGARH 11 SCHOOL OF NURSING, GMSH-16, 483011 NEHA ROHILLA NARESH KUMAR 324 CHANDIGARH ROHILLA 12 SCHOOL OF NURSING, GMSH-16, 483012 PAYAL NEGI SOBAN SINGH NEGI 346 CHANDIGARH Page 1 of 304 RESULT OF GNM 1ST YEAR EXAM HELD IN DECEMBER - 2018 S. -

Sl No Roll App Name Fathername Dob 1 9206000285

PROVISIONALLY ADMITTED CANDIDATES LIST FOR RECRUITMENT OF SUB INSPECTORS IN CAPFs, AND ASSISTANT SUB INSPECTOR IN CISF ‐2012 TO BE HELD ON 27.05.