10-Bearez 1073 [Cybium 2018, 423]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Political Biogeography of Migratory Marine Predators

1 The political biogeography of migratory marine predators 2 Authors: Autumn-Lynn Harrison1, 2*, Daniel P. Costa1, Arliss J. Winship3,4, Scott R. Benson5,6, 3 Steven J. Bograd7, Michelle Antolos1, Aaron B. Carlisle8,9, Heidi Dewar10, Peter H. Dutton11, Sal 4 J. Jorgensen12, Suzanne Kohin10, Bruce R. Mate13, Patrick W. Robinson1, Kurt M. Schaefer14, 5 Scott A. Shaffer15, George L. Shillinger16,17,8, Samantha E. Simmons18, Kevin C. Weng19, 6 Kristina M. Gjerde20, Barbara A. Block8 7 1University of California, Santa Cruz, Department of Ecology & Evolutionary Biology, Long 8 Marine Laboratory, Santa Cruz, California 95060, USA. 9 2 Migratory Bird Center, Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute, National Zoological Park, 10 Washington, D.C. 20008, USA. 11 3NOAA/NOS/NCCOS/Marine Spatial Ecology Division/Biogeography Branch, 1305 East 12 West Highway, Silver Spring, Maryland, 20910, USA. 13 4CSS Inc., 10301 Democracy Lane, Suite 300, Fairfax, VA 22030, USA. 14 5Marine Mammal and Turtle Division, Southwest Fisheries Science Center, National Marine 15 Fisheries Service, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Moss Landing, 16 California 95039, USA. 17 6Moss Landing Marine Laboratories, Moss Landing, CA 95039 USA 18 7Environmental Research Division, Southwest Fisheries Science Center, National Marine 19 Fisheries Service, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, 99 Pacific Street, 20 Monterey, California 93940, USA. 21 8Hopkins Marine Station, Department of Biology, Stanford University, 120 Oceanview 22 Boulevard, Pacific Grove, California 93950 USA. 23 9University of Delaware, School of Marine Science and Policy, 700 Pilottown Rd, Lewes, 24 Delaware, 19958 USA. 25 10Fisheries Resources Division, Southwest Fisheries Science Center, National Marine 26 Fisheries Service, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, La Jolla, CA 92037, 27 USA. -

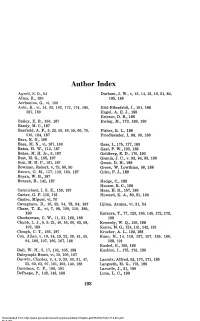

Author Index

Author Index Agrell, S. 0., 54 Durham, J. W., v, 13, 14, 15, 16, 51, 84, Allen, R., 190 105, 188 Arrhenius, G., vi, 169 Aoki, K, vi, 14, 52, 162, 172, 174, 185, Eibl-Eibesfeldt, I., 101, 188 187, 189 Engel, A. E. J., 188 Ericson, D. B., 188 Bailey, E. B., 166, 187 Ewing, M., 170, 188, 189 Bandy, M. C., 187 Banfield, A. F., 5, 22, 55, 56, 59, 60, 70, Fisher, R. L., 188 110, 124, 187 Friedlaender, I, 98, 99, 188 Barr, K. G., 190 Bass, M. N., vi, 167, 169 Gass, I., 175, 177, 189 Bates, H. W., 113, 187 Gast, P. W., 133, 188 Behre, M. H. Jr., 5, 187 Goldberg, E. D., 170, 190 Best, M. G„ 165, 187 Granja, J. C., v, 83, 84, 85, 188 Bott, M. H. P., 181, 187 Green, D. H., 188 Bowman, Robert, v, 79, 80, 90 Green, W. Lowthian, 98, 188 Brown, G. M., 157, 159, 160, 187 Grim, P. J., 189 Bryan, W. B., 187 Bunsen, R., 141, 187 Hedge, C., 188 Heezen, B. C., 188 Carmichael, I. S. E., 159, 187 Hess, H. H„ 157, 188 Carter, G. F. 115, 191 Howard, K. A., 80, 81,190 Castro, Miguel, vi, 76 Cavagnaro, D., 16, 33, 34, 78, 94, 187 Iljima, Azuma, vi, 31, 54 Chase, T. E., vi, 7, 98, 109, 110, 189, 190 Katsura, T., 77, 125, 136, 145, 172, 173, Chesterman, C. W., 11, 31, 168, 188 189 Chubb, L. J., 5, 9, 21, 46, 55, 60, 63, 98, Kennedy, W. -

Marine Biodiversity in Juan Fernández and Desventuradas Islands, Chile: Global Endemism Hotspots

RESEARCH ARTICLE Marine Biodiversity in Juan Fernández and Desventuradas Islands, Chile: Global Endemism Hotspots Alan M. Friedlander1,2,3*, Enric Ballesteros4, Jennifer E. Caselle5, Carlos F. Gaymer3,6,7,8, Alvaro T. Palma9, Ignacio Petit6, Eduardo Varas9, Alex Muñoz Wilson10, Enric Sala1 1 Pristine Seas, National Geographic Society, Washington, District of Columbia, United States of America, 2 Fisheries Ecology Research Lab, University of Hawaii, Honolulu, Hawaii, United States of America, 3 Millennium Nucleus for Ecology and Sustainable Management of Oceanic Islands (ESMOI), Coquimbo, Chile, 4 Centre d'Estudis Avançats (CEAB-CSIC), Blanes, Spain, 5 Marine Science Institute, University of California Santa Barbara, Santa Barbara, California, United States of America, 6 Universidad Católica del Norte, Coquimbo, Chile, 7 Centro de Estudios Avanzados en Zonas Áridas, Coquimbo, Chile, 8 Instituto de Ecología y Biodiversidad, Coquimbo, Chile, 9 FisioAqua, Santiago, Chile, 10 OCEANA, SA, Santiago, Chile * [email protected] OPEN ACCESS Abstract Citation: Friedlander AM, Ballesteros E, Caselle JE, Gaymer CF, Palma AT, Petit I, et al. (2016) Marine The Juan Fernández and Desventuradas islands are among the few oceanic islands Biodiversity in Juan Fernández and Desventuradas belonging to Chile. They possess a unique mix of tropical, subtropical, and temperate Islands, Chile: Global Endemism Hotspots. PLoS marine species, and although close to continental South America, elements of the biota ONE 11(1): e0145059. doi:10.1371/journal. pone.0145059 have greater affinities with the central and south Pacific owing to the Humboldt Current, which creates a strong biogeographic barrier between these islands and the continent. The Editor: Christopher J Fulton, The Australian National University, AUSTRALIA Juan Fernández Archipelago has ~700 people, with the major industry being the fishery for the endemic lobster, Jasus frontalis. -

Bryozoa De La Placa De Nazca Con Énfasis En Las Islas Desventuradas

Cienc. Tecnol. Mar, 28 (1): 75-90, 2005 Bryozoa de la Placa de Nazca 75 BRYOZOA DE LA PLACA DE NAZCA CON ÉNFASIS EN LAS ISLAS DESVENTURADAS ON THE NAZCA PLATE BRYOZOANS WITH EMPHASIS ON DESVENTURADAS ISLANDS HUGO I. MOYANO G. Departamento de Zoología Universidad de Concepción Casilla 160-C Concepción Recepción: 27 de abril de 2004 – Versión corregida aceptada: 1 de octubre de 2004. RESUMEN Esta es una revisión parcial de las faunas de briozoos conocidas hasta ahora provenientes de la Placa de Nazca. A partir de las publicaciones preexistentes y del examen de algunas muestras se compa- raron zoogeográficamente Pascua (PAS), Salas y Gómez (SG), Juan Fernández (JF), Desventuradas (DES) y Galápagos (GAL). Para la comparación se utilizaron tres conjuntos de 115, 140 y 170 géneros de los territorios insulares ya indicados, los que incluyen también aquellos de las costas chileno-peruanas influi- das por la corriente de Humboldt (CHP) y los de las islas Kermadec (KE). Los dendrogramas resultantes demuestran que los territorios insulares más afines son los de Juan Fernández y las Desventuradas en términos de afinidad genérica briozoológica. El dendrograma basado en 170 géneros de los órdenes Ctenostomatida y Cheilostomatida muestra dos conjuntos principales a saber: a) JF, DES y CHP y b) PAS, GA y KE a los cuales se une solitariamente SG. Sobre la base de la comparación a nivel genérico indicada más arriba, para las islas Desventura- das no se justifica un status zoogeográfico separado de nivel de provincia tropical sino que debería integrarse a la provincia temperado-cálida de Juan Fernández. -

Redalyc.Initial Assessment of Coastal Benthic Communities in the Marine Parks at Robinson Crusoe Island

Latin American Journal of Aquatic Research E-ISSN: 0718-560X [email protected] Pontificia Universidad Católica de Valparaíso Chile Rodríguez-Ruiz, Montserrat C.; Andreu-Cazenave, Miguel; Ruz, Catalina S.; Ruano- Chamorro, Cristina; Ramírez, Fabián; González, Catherine; Carrasco, Sergio A.; Pérez- Matus, Alejandro; Fernández, Miriam Initial assessment of coastal benthic communities in the Marine Parks at Robinson Crusoe Island Latin American Journal of Aquatic Research, vol. 42, núm. 4, octubre, 2014, pp. 918-936 Pontificia Universidad Católica de Valparaíso Valparaíso, Chile Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=175032366016 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative Lat. Am. J. Aquat. Res., 42(4): 918-936, 2014 Marine parks at Robinson Crusoe Island 918889 “Oceanography and Marine Resources of Oceanic Islands of Southeastern Pacific ” M. Fernández & S. Hormazábal (Guest Editors) DOI: 10.3856/vol42-issue4-fulltext-16 Research Article Initial assessment of coastal benthic communities in the Marine Parks at Robinson Crusoe Island Montserrat C. Rodríguez-Ruiz1, Miguel Andreu-Cazenave1, Catalina S. Ruz2 Cristina Ruano-Chamorro1, Fabián Ramírez2, Catherine González1, Sergio A. Carrasco2 Alejandro Pérez-Matus2 & Miriam Fernández1 1Estación Costera de Investigaciones Marinas and Center for Marine Conservation, Facultad de Ciencias Biológicas, Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile, P.O. Box 114-D, Santiago, Chile 2Subtidal Ecology Laboratory and Center for Marine Conservation, Estación Costera de Investigaciones Marinas, Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile, P.O. Box 114-D, Santiago, Chile ABSTRACT. -

Research Opportunities in Biomedical Sciences

STREAMS - Research Opportunities in Biomedical Sciences WSU Boonshoft School of Medicine 3640 Colonel Glenn Highway Dayton, OH 45435-0001 APPLICATION (please type or print legibly) *Required information *Name_____________________________________ Social Security #____________________________________ *Undergraduate Institution_______________________________________________________________________ *Date of Birth: Class: Freshman Sophomore Junior Senior Post-bac Major_____________________________________ Expected date of graduation___________________________ SAT (or ACT) scores: VERB_________MATH_________Test Date_________GPA__________ *Applicant’s Current Mailing Address *Mailing Address After ____________(Give date) _________________________________________ _________________________________________ _________________________________________ _________________________________________ _________________________________________ _________________________________________ Phone # : Day (____)_______________________ Phone # : Day (____)_______________________ Eve (____)_______________________ Eve (____)_______________________ *Email Address:_____________________________ FAX number: (____)_______________________ Where did you learn about this program?:__________________________________________________________ *Are you a U.S. citizen or permanent resident? Yes No (You must be a citizen or permanent resident to participate in this program) *Please indicate the group(s) in which you would include yourself: Native American/Alaskan Native Black/African-American -

Cq Dx Zones of the World

180 W 170 W 160 W 150 W 140 W 130 W 120 W 110 W 100 W 90 W 80 W 70 W 60 W 50 W 40 W 30 W 20 W 10 W 10 E 20 E 30 E 40 E 50 E 60 E 70 E 80 E 90 E 100 E 110 E 120 E 130 E 140 E 150 E 160 E 170 E 180 E -2 +4 CQ DX ZONES Franz Josef Land OF THE WORLD (Russia) ITU DX Zones of the world N can be viewed on the back. 80 Svalbard (Norway) -12 -11 -10 -9 -8 -7 -6 -5 -4 -3 +1 +2 +3 +5 +7 +9 +10 +11 +12 19 1 2 40 -1 Jan Mayen (Norway) +11 70 N 70 Greenland +1 +2 Finland Alaska, U.S. Iceland Faroe Island (Denmark) 14 Norway Sweden 15 16 17 18 19 International Date Line 60 N 60 Estonia Russia Canada Latvia Denmark Lithuania +7 Northern Ireland +3 +5 +6 +8 +9 +10 (UK) Russia/Kaliningrad -10 Ireland United Kingdom Belarus Netherlands Germany Poland Belgium Luxembourg 50 N 50 Guernsey Czech Republic Ukraine Jersey Slovakia St. Pierre and Miquelon Liechtenstein Kazakhstan Austria France Switzerland Hungary Moldova Slovenia Mongolia Croatia Romania Bosnia- Serbia Monaco Herzegovina 1 Corsica Bulgaria Montenegro Georgia Uzbekistan Andorra (France) Italy Macedonia Azores Albania Kyrgyzstan Portugal Spain Sardinia Armenia+4 Azerbaijan 40 N 40 3 4 5 (Portugal) (Italy) Turkmenistan North Korea Greece Turkey United States Balearic Is. Tajikistan +1 Day NOTES: (Spain) 20 23 South Korea Gibraltar Japan Tunisia Malta China Cyprus Syria Iran Madeira Lebanon +4.5 +8 This CQ DX zones map and the ITU zones map on the reverse side use (Portugal) Bermuda Iraq +3.5 Afghanistan an Albers Equal Area projection and is current as of July 2010. -

Diversity and Distribution of Chilean Benthic Marine Polychaetes: State of the Art

BULLETIN OF MARINE SCIENCE, 67(1): 359–372, 2000 DIVERSITY AND DISTRIBUTION OF CHILEAN BENTHIC MARINE POLYCHAETES: STATE OF THE ART Nicolás Rozbaczylo and Javier A. Simonetti ABSTRACT Current knowledge of Chilean benthic marine polychaetes is reviewed. The history of the studies, researchers involved, the rate and localities of species descriptions are pre- sented, as they relate to the assessment of biogeographic units along the Chilean coast. Taxonomic richness along the Chilean coast is associated with differential sampling ef- forts weakening the assessment of biogeographic units. Juan Ignacio Molina (1740–1829), in his pioneer work on the biological diversity of Chile, Saggio sulla storia naturale del Chili published in 1782, described numerous in- vertebrate species. However, he did not refer to polychaetes. The first descriptions of polychaetes from continental Chile were published in 1849. Based on specimens col- lected by the French naturalist Claudio Gay, all 15 species were described by Blanchard (1849) as new to science (Rozbaczylo, 1985). During the following years, the knowledge of Chilean polychaetes increased due principally to the activity of foreign expeditions and researchers who visited various places of Chile. In the last 30 yrs, the taxonomic knowledge of polychaetes has been increasing largely due to the work of Chilean scien- tists who have done studies on local faunas or reviewed specific groups of polychaetes. With almost 450 species known, this figure is considered an underestimate due to the overall scarcity of research carried out on Chilean polychaetes (Rozbaczylo and Carrasco, 1995). In this work we analyze the knowledge of benthic polychaetes along the Chilean conti- nental coast and oceanic islands, in terms of the taxonomic richness, the main expeditions that have collected specimens in these areas, the researchers who have studied this mate- rial, and location of the main collections containing type specimens of Chilean species, as they relate to the assessment of faunal provinces. -

Conservation, Restoration, and Development of the Juan Fernandez Islands, Chile"

Revista Chilena de Historia Natural 74:899-910, 2001 DOCUMENT Project "Conservation, Restoration, and Development of the Juan Fernandez islands, Chile" Proyecto conservaci6n, restauraci6n y desarrollo de las islas Juan Fernandez, Chile JAIME G. CUEVAS 1 & GART VAN LEERSUM 1Corresponding author: Corporaci6n Nacional Forestal, Parque Nacional Archipielago de Juan Fernandez, Vicente Gonzalez 130, Isla Robinson Crusoe, Chile ABSTRACT From a scientific point of view, the Juan Fernandez islands contain one of the most interesting floras of the planet. Although protected as a National Park and a World Biosphere Reserve, 400 years of human interference have left deep traces in the native plant communities. Repeated burning, overexploitation of species, and the introduction of animal and plant plagues have taken 75 % of the endemic vascular flora to the verge of extinction. In 1997, Chile's national forest service (Corporaci6n Nacional Forestal, CONAF) started an ambitious project, whose objective is the recovery of this highly complex ecosystem with a socio-ecological focus. Juan Fernandez makes an interesting case, as the local people (600 persons) practically live within the park, therefore impeding the exclusion of the people from any 2 conservation program. Secondly, the relatively small size of the archipelago (100 km ) permits the observation of the effects of whatever modification in the ecosystem on small scales in time and space. Thirdly, the native and introduced biota are interrelated in such a way that human-caused changes in one species population may provoke unexpected results amongst other, non-target species. The project mainly deals with the eradication or control of some animal and plant plagues, the active conservation and restoration of the flora and the inclusion of the local people in conservation planning. -

Humboldt Current and the Juan Fernández Archipelago November 2014

Expedition Research Report Humboldt Current and the Juan Fernández archipelago November 2014 Expedition Team Robert L. Flood, Angus C. Wilson, Kirk Zufelt Mike Danzenbaker, John Ryan & John Shemilt Juan Fernández Petrel KZ Stejneger’s Petrel AW First published August 2017 by www.scillypelagics.com © text: the authors © video clips: the copyright in the video clips shall remain with each individual videographer © photographs: the copyright in the photographs shall remain with each individual photographer, named in the caption of each photograph All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form or by any means – graphic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, taping or information storage and retrieval systems – without the prior permission in writing of the publishers. 2 CONTENTS Report Summary 4 Introduction 4 Itinerary and Conditions 5 Bird Species Accounts 6 Summary 6 Humboldt Current and Coquimbo Bay 7 Passages Humboldt Current to Juan Fernández and return 13 At sea off the Juan Fernández archipelago 18 Ashore on Robinson Crusoe Island 26 Cetaceans and Pinnipeds 28 Acknowledgements 29 References 29 Appendix: Alpha Codes 30 White-bellied Storm-petrel JR 3 REPORT SUMMARY This report summarises our observations of seabirds seen during an expedition from Chile to the Juan Fernández archipelago and return, with six days in the Humboldt Current. Observations are summarised by marine habitat – Humboldt Current, oceanic passages between the Humboldt Current and the Juan Fernández archipelago, and waters around the Juan Fernández archipelago. Also summarised are land bird observations in the Juan Fernández archipelago, and cetaceans and pinnipeds seen during the expedition. Points of interest are briefly discussed. -

Taxonomic Treatment of Cichorieae (Asteraceae) Endemic to the Juan Fernández and Desventuradas Islands (SE Pacific)

Ann. Bot. Fennici 49: 171–178 ISSN 0003-3847 (print) ISSN 1797-2442 (online) Helsinki 29 June 2012 © Finnish Zoological and Botanical Publishing Board 2012 Taxonomic treatment of Cichorieae (Asteraceae) endemic to the Juan Fernández and Desventuradas Islands (SE Pacific) José A. Mejías1,* & Seung-Chul Kim2 1) Department of Plant Biology and Ecology, University of Seville, Avda. Reina Mercedes 6, ES-41012 Seville, Spain (*corresponding author’s e-mail: [email protected]) 2) Department of Biological Sciences, Sungkyunkwan University, 2066 Seobu-ro, Jangan-Gu, Suwon, Korea 440-746 Received 29 June 2011, final version received 15 Nov. 2011, accepted 16 Nov. 2011 Mejías, J. A. & Kim, S. C. 2012: Taxonomic treatment of Cichorieae (Asteraceae) endemic to the Juan Fernández and Desventuradas Islands (SE Pacific). — Ann. Bot. Fennici 49: 171–178. The evolutionary origin and taxonomic position of Dendroseris and Thamnoseris (Cichorieae, Asteraceae) are discussed in the light of recent molecular systematic studies. Based on the previous development of a robust phylogenetic framework, we support the inclusion of the group as a subgenus integrated within a new and broad concept of the genus Sonchus. This approach retains information on the evolutionary relationships of the group which most likely originated from an adaptive radiation process; furthermore, it also promotes holophyly in the subtribe Hyoseridinae (for- merly Sonchinae). Consequently, all the former Dendroseris and Thamnoseris species must be transferred to Sonchus. A preliminary nomenclatural synopsis of the proposed subgenus is given here, including the new required combinations. Introduction Within the tribe Cichorieae, the most prominent cases occur on the Canary Islands Adaptive radiation on oceanic islands has (NE Atlantic Ocean), and on the Juan Fern- yielded spectacular and explosive in-situ diversi- ández Islands (SE Pacific Ocean) (Crawford fication of plants (Carlquist 1974: 22–23), which et al. -

Plant Geography of Chile PLANT and VEGETATION

Plant Geography of Chile PLANT AND VEGETATION Volume 5 Series Editor: M.J.A. Werger For further volumes: http://www.springer.com/series/7549 Plant Geography of Chile by Andrés Moreira-Muñoz Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile, Santiago, Chile 123 Dr. Andrés Moreira-Muñoz Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile Instituto de Geografia Av. Vicuña Mackenna 4860, Santiago Chile [email protected] ISSN 1875-1318 e-ISSN 1875-1326 ISBN 978-90-481-8747-8 e-ISBN 978-90-481-8748-5 DOI 10.1007/978-90-481-8748-5 Springer Dordrecht Heidelberg London New York © Springer Science+Business Media B.V. 2011 No part of this work may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, microfilming, recording or otherwise, without written permission from the Publisher, with the exception of any material supplied specifically for the purpose of being entered and executed on a computer system, for exclusive use by the purchaser of the work. ◦ ◦ Cover illustration: High-Andean vegetation at Laguna Miscanti (23 43 S, 67 47 W, 4350 m asl) Printed on acid-free paper Springer is part of Springer Science+Business Media (www.springer.com) Carlos Reiche (1860–1929) In Memoriam Foreword It is not just the brilliant and dramatic scenery that makes Chile such an attractive part of the world. No, that country has so very much more! And certainly it has a rich and beautiful flora. Chile’s plant world is strongly diversified and shows inter- esting geographical and evolutionary patterns. This is due to several factors: The geographical position of the country on the edge of a continental plate and stretch- ing along an extremely long latitudinal gradient from the tropics to the cold, barren rocks of Cape Horn, opposite Antarctica; the strong differences in altitude from sea level to the icy peaks of the Andes; the inclusion of distant islands in the country’s territory; the long geological and evolutionary history of the biota; and the mixture of tropical and temperate floras.