Bilateral Ossification of the Stylohyoid Ligament

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Eagle's Syndrome, Elongated Styloid Process and New

Musculoskeletal Science and Practice 50 (2020) 102219 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Musculoskeletal Science and Practice journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/msksp Masterclass Eagle’s syndrome, elongated styloid process and new evidence for pre-manipulative precautions for potential cervical arterial dysfunction Andrea M. Westbrook a,*, Vincent J. Kabbaz b, Christopher R. Showalter c a Method Manual Physical Therapy & Wellness, Raleigh, NC, 27617, USA b HEAL Physical Therapy, Monona, WI, USA c Program Director, MAPS Accredited Fellowship in Orthopedic Manual Therapy, Cutchogue, NY, 11935, USA ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: Introduction: Safety with upper cervical interventions is a frequently discussed and updated concern for physical Eagle’s syndrome therapists, chiropractors and osteopaths. IFOMPT developed the framework for safety assessment of the cervical Styloid spine, and this topic has been discussed in-depth with past masterclasses characterizing carotid artery dissection CAD and cervical arterial dysfunction. Our masterclass will expand on this information with knowledge of specific Carotid anatomical anomalies found to produce Eagle’s syndrome, and cause carotid artery dissection, stroke and even Autonomic Manipulation death. Eagle’s syndrome is an underdiagnosed, multi-mechanism symptom assortment produced by provocation of the sensitive carotid space structures by styloid process anomalies. As the styloid traverses between the internal and external carotid arteries, provocation of the vessels and periarterial sympathetic nerve fiberscan lead to various neural, vascular and autonomic symptoms. Eagle’s syndrome commonly presents as neck, facial and jaw pain, headache and arm paresthesias; problems physical therapists frequently evaluate and treat. Purpose: This masterclass aims to outline the safety concerns, assessment and management of patients with Eagle’s syndrome and styloid anomalies. -

Deep Neck Infections 55

Deep Neck Infections 55 Behrad B. Aynehchi Gady Har-El Deep neck space infections (DNSIs) are a relatively penetrating trauma, surgical instrument trauma, spread infrequent entity in the postpenicillin era. Their occur- from superfi cial infections, necrotic malignant nodes, rence, however, poses considerable challenges in diagnosis mastoiditis with resultant Bezold abscess, and unknown and treatment and they may result in potentially serious causes (3–5). In inner cities, where intravenous drug or even fatal complications in the absence of timely rec- abuse (IVDA) is more common, there is a higher preva- ognition. The advent of antibiotics has led to a continu- lence of infections of the jugular vein and carotid sheath ing evolution in etiology, presentation, clinical course, and from contaminated needles (6–8). The emerging practice antimicrobial resistance patterns. These trends combined of “shotgunning” crack cocaine has been associated with with the complex anatomy of the head and neck under- retropharyngeal abscesses as well (9). These purulent col- score the importance of clinical suspicion and thorough lections from direct inoculation, however, seem to have a diagnostic evaluation. Proper management of a recog- more benign clinical course compared to those spreading nized DNSI begins with securing the airway. Despite recent from infl amed tissue (10). Congenital anomalies includ- advances in imaging and conservative medical manage- ing thyroglossal duct cysts and branchial cleft anomalies ment, surgical drainage remains a mainstay in the treat- must also be considered, particularly in cases where no ment in many cases. apparent source can be readily identifi ed. Regardless of the etiology, infection and infl ammation can spread through- Q1 ETIOLOGY out the various regions via arteries, veins, lymphatics, or direct extension along fascial planes. -

Morfofunctional Structure of the Skull

N.L. Svintsytska V.H. Hryn Morfofunctional structure of the skull Study guide Poltava 2016 Ministry of Public Health of Ukraine Public Institution «Central Methodological Office for Higher Medical Education of MPH of Ukraine» Higher State Educational Establishment of Ukraine «Ukranian Medical Stomatological Academy» N.L. Svintsytska, V.H. Hryn Morfofunctional structure of the skull Study guide Poltava 2016 2 LBC 28.706 UDC 611.714/716 S 24 «Recommended by the Ministry of Health of Ukraine as textbook for English- speaking students of higher educational institutions of the MPH of Ukraine» (minutes of the meeting of the Commission for the organization of training and methodical literature for the persons enrolled in higher medical (pharmaceutical) educational establishments of postgraduate education MPH of Ukraine, from 02.06.2016 №2). Letter of the MPH of Ukraine of 11.07.2016 № 08.01-30/17321 Composed by: N.L. Svintsytska, Associate Professor at the Department of Human Anatomy of Higher State Educational Establishment of Ukraine «Ukrainian Medical Stomatological Academy», PhD in Medicine, Associate Professor V.H. Hryn, Associate Professor at the Department of Human Anatomy of Higher State Educational Establishment of Ukraine «Ukrainian Medical Stomatological Academy», PhD in Medicine, Associate Professor This textbook is intended for undergraduate, postgraduate students and continuing education of health care professionals in a variety of clinical disciplines (medicine, pediatrics, dentistry) as it includes the basic concepts of human anatomy of the skull in adults and newborns. Rewiewed by: O.M. Slobodian, Head of the Department of Anatomy, Topographic Anatomy and Operative Surgery of Higher State Educational Establishment of Ukraine «Bukovinian State Medical University», Doctor of Medical Sciences, Professor M.V. -

Tenderness Over the Hyoid Bone Can Indicate Epiglottitis in Adults

J Am Board Fam Med: first published as 10.3122/jabfm.19.5.517 on 1 September 2006. Downloaded from Tenderness Over the Hyoid Bone Can Indicate Epiglottitis in Adults Hiroshi Ehara, MD Adult acute epiglottitis is a rare but life-threatening disease caused by obstruction of the airway. The symptoms and signs of this disease may be nonspecific without apparent airway compromise. We en- countered 3 consecutive cases of adult patients with this disease in a single 5-month period in one phy- sician’s office. In all cases, physical examination revealed tenderness of the anterior neck over the hyoid bone. These observations assisted us in identifying this rare disease quickly. We suggest that tenderness over the hyoid bone should raise suspicion of adult acute epiglottitis. (J Am Board Fam Med 2006;19: 517–20.) Adult acute epiglottitis is an inflammatory disease power, and talking aggravated her sore throat. At of the epiglottis and adjacent structures resulting admission, the patient did not seem to be critically from infection. It can be a rapidly fatal condition ill. Her voice was neither muffled nor hoarse. The because of the potential for sudden upper airway vital signs indicating the nature of her condition obstruction. Early recognition of acute epiglottitis were as follows: body temperature, 37.0°C (axil- is therefore of the utmost importance in minimiz- lary); blood pressure, 90/64 mm Hg; pulse, 64/min; ing morbidity and mortality. respirations, 24/min; peripheral oxygen saturation, Unfortunately, misdiagnosis occurs in 23% to 97%. At this point, these findings were not suffi- 1–3 31% of the cases of adult acute epiglottitis. -

Parts of the Body 1) Head – Caput, Capitus 2) Skull- Cranium Cephalic- Toward the Skull Caudal- Toward the Tail Rostral- Toward the Nose 3) Collum (Pl

BIO 3330 Advanced Human Cadaver Anatomy Instructor: Dr. Jeff Simpson Department of Biology Metropolitan State College of Denver 1 PARTS OF THE BODY 1) HEAD – CAPUT, CAPITUS 2) SKULL- CRANIUM CEPHALIC- TOWARD THE SKULL CAUDAL- TOWARD THE TAIL ROSTRAL- TOWARD THE NOSE 3) COLLUM (PL. COLLI), CERVIX 4) TRUNK- THORAX, CHEST 5) ABDOMEN- AREA BETWEEN THE DIAPHRAGM AND THE HIP BONES 6) PELVIS- AREA BETWEEN OS COXAS EXTREMITIES -UPPER 1) SHOULDER GIRDLE - SCAPULA, CLAVICLE 2) BRACHIUM - ARM 3) ANTEBRACHIUM -FOREARM 4) CUBITAL FOSSA 6) METACARPALS 7) PHALANGES 2 Lower Extremities Pelvis Os Coxae (2) Inominant Bones Sacrum Coccyx Terms of Position and Direction Anatomical Position Body Erect, head, eyes and toes facing forward. Limbs at side, palms facing forward Anterior-ventral Posterior-dorsal Superficial Deep Internal/external Vertical & horizontal- refer to the body in the standing position Lateral/ medial Superior/inferior Ipsilateral Contralateral Planes of the Body Median-cuts the body into left and right halves Sagittal- parallel to median Frontal (Coronal)- divides the body into front and back halves 3 Horizontal(transverse)- cuts the body into upper and lower portions Positions of the Body Proximal Distal Limbs Radial Ulnar Tibial Fibular Foot Dorsum Plantar Hallicus HAND Dorsum- back of hand Palmar (volar)- palm side Pollicus Index finger Middle finger Ring finger Pinky finger TERMS OF MOVEMENT 1) FLEXION: DECREASE ANGLE BETWEEN TWO BONES OF A JOINT 2) EXTENSION: INCREASE ANGLE BETWEEN TWO BONES OF A JOINT 3) ADDUCTION: TOWARDS MIDLINE -

Calcio, Fósforo Y Vitamina D) Con Las Alteraciones Del Complejo Estilohioideo

TESIS DOCTORAL ANÁLISIS DE LA RELACIÓN ENTRE LOS PARÁMETROS ANALÍTICOS SÉRICOS DEL METABOLISMO ÓSEO (CALCIO, FÓSFORO Y VITAMINA D) CON LAS ALTERACIONES DEL COMPLEJO ESTILOHIOIDEO CARLOS MIGUEL SALVADOR RAMÍREZ Directores: Ana Sánchez del Rey y Agustín Martínez Ibargüen Facultad de Medicina y Enfermería 2018 (c)2018 CARLOS MIGUEL SALVADOR RAMIREZ “No tienes que ser grande para comenzar, pero tienes que comenzar para ser grande”. Zig Ziglar AGRADECIMIENTOS La elaboración del presente trabajo ha significado el resultado de un gran esfuerzo personal; pero deseo señalar, ya con la satisfacción de haber alcanzado el objetivo, la valiosa implicación y colaboración de todos quienes me ayudaron y animaron en esta labor. El inicio de mi interés por el estudio del complejo estilohioideo se dio desde mi etapa como residente ORL y como docente de prácticas universitarias, por lo que destaco la colaboración de parte del servicio de Otorrinolaringología del Hospital Universitario Basurto-Bilbao y de la cátedra de Anatomía y Embriología Humana UPV/EHU (Dra. Concepción Reblet López). A cada uno de los pacientes, quienes prestaron su tiempo y buena disposición a participar en el presente estudio. A los compañeros del Hospital Medina del Campo, en especial al equipo del servicio de Otorrinolaríngología, servicio de Laboratorio Clínico, servicio de Medicina Preventiva (Dra. María del Carmen Viña Simón), servicio de Radiodiagnóstico, residente: Dra. Jenny Dávalos Marín. A María Fé Muñoz Moreno, responsable de Metodología y Bioestadística de la Unidad de apoyo a la investigación del Hospital Clínico Universitario de Valladolid, cuya colaboración ha sido fundamental para el análisis de los resultados encontrados. A Lourdes Sáenz de Castillo, de la Biblioteca del Campus de Álava UPV/EHU, por la colaboración en la obtención de material bibliográfico. -

Atlas of the Facial Nerve and Related Structures

Rhoton Yoshioka Atlas of the Facial Nerve Unique Atlas Opens Window and Related Structures Into Facial Nerve Anatomy… Atlas of the Facial Nerve and Related Structures and Related Nerve Facial of the Atlas “His meticulous methods of anatomical dissection and microsurgical techniques helped transform the primitive specialty of neurosurgery into the magnificent surgical discipline that it is today.”— Nobutaka Yoshioka American Association of Neurological Surgeons. Albert L. Rhoton, Jr. Nobutaka Yoshioka, MD, PhD and Albert L. Rhoton, Jr., MD have created an anatomical atlas of astounding precision. An unparalleled teaching tool, this atlas opens a unique window into the anatomical intricacies of complex facial nerves and related structures. An internationally renowned author, educator, brain anatomist, and neurosurgeon, Dr. Rhoton is regarded by colleagues as one of the fathers of modern microscopic neurosurgery. Dr. Yoshioka, an esteemed craniofacial reconstructive surgeon in Japan, mastered this precise dissection technique while undertaking a fellowship at Dr. Rhoton’s microanatomy lab, writing in the preface that within such precision images lies potential for surgical innovation. Special Features • Exquisite color photographs, prepared from carefully dissected latex injected cadavers, reveal anatomy layer by layer with remarkable detail and clarity • An added highlight, 3-D versions of these extraordinary images, are available online in the Thieme MediaCenter • Major sections include intracranial region and skull, upper facial and midfacial region, and lower facial and posterolateral neck region Organized by region, each layered dissection elucidates specific nerves and structures with pinpoint accuracy, providing the clinician with in-depth anatomical insights. Precise clinical explanations accompany each photograph. In tandem, the images and text provide an excellent foundation for understanding the nerves and structures impacted by neurosurgical-related pathologies as well as other conditions and injuries. -

Evaluation of the Elongation and Calcification Patterns of the Styloid Process with Digital Panoramic Radiography

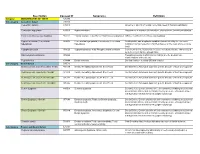

Evaluation of the Elongation and Calcification Patterns of the Styloid Process with Digital Panoramic Radiography Abstract Original Article Introdouction: typeThe styloid your textprocess(SP) ....... has the potential for cal- Khojastepour Leila 1, Dastan Farivar2, Ezoddini-Arda- cification and ossification. The aim of this study kani Fatemeh 3 was to investigate the prevalence of different pat- terns of elongation and calcification of the SP. Materials and methods: typeIn this your cross-sectional text ....... study, 400 digital pano- ramic radiographs taken for routine dental exam- ination in the dental school of Shiraz University were evaluated for the radiographic features of an elongated styloid process (ESP). The appar- 1 Professor, Department of Oral and Maxillofacial ent length of SP was measured with Scanora Radiology, Faculty of Dentistry, Shiraz University of software on panoramic of 350 patient who met Medial Science, Shiraz, Iran. the study criteria, ( 204 females and 146 males). 2 Dental student. Department of Oral and Maxillofa- Lengths greater than 30mm were consider as ESP. cial Radiology Faculty of Dentisty, Shiraz University ESP were also classified into three types based of Medical Sciences, Shiraz, Iran. on Langlais classification (elongated, pseudo -ar 3 Professor. Department of Oral and Maxillofacial ticulated; and segmented ). Data were analyzed Radiology Faculty of Dentisty, Shahid Sadough Uni- Results: versity of Medical Sciences Yazd, Iran . typeby the your Chi squaredtext ....... tests and Student’s t-tests . Results: Received:Received:17 May 2015 ESP was confirmed in 153 patients including 78 Accepted: 25 Jun 2015 males and 75 females (43.7%). The prevalence of ESP was significantly higher in males. -

The Axial Skeleton – Hyoid Bone

Marieb’s Human Anatomy and Physiology Ninth Edition Marieb Hoehn Chapter 7 The Axial and Appendicular Skeleton Lecture 14 1 Lecture Overview • Axial Skeleton – Hyoid bone – Bones of the orbit – Paranasal sinuses – Infantile skull – Vertebral column • Curves • Intervertebral disks –Ribs 2 The Axial Skeleton – Hyoid Bone Figure from: Saladin, Anatomy & Physiology, McGraw Hill, 2007 Suspended from the styloid processes of the temporal bones by ligaments and muscles The hyoid bone supports the larynx and is the site of attachment for the muscles of the larynx, pharynx, and tongue 3 1 Axial Skeleton – the Orbit See Fig. 7.6.1 in Martini and Fig. 7.20 in Figure: Martini, Right Hole’s Textbook Anatomy & Physiology, Optic canal – Optic nerve; Prentice Hall, 2001 opthalmic artery Superior orbital fissure – Oculomotor nerve, trochlear nerve, opthalmic branch of trigeminal nerve, abducens nerve; opthalmic vein F Inferior orbital fissure – Maxillary branch of trigeminal nerve E Z S L Infraorbital groove – M N Infraorbital nerve, maxillary branch of trigeminal nerve, M infraorbital artery Lacrimal sulcus – Lacrimal sac and tearduct *Be able to label a diagram of the orbit for lecture exam 4 Nasal Cavities and Sinuses Paranasal sinuses are air-filled, Figure: Martini, mucous membrane-lined Anatomy & Physiology, chambers connected to the nasal Prentice Hall, 2001 cavity. Superior wall of nasal cavities is formed by frontal, ethmoid, and sphenoid bones Lateral wall of nasal cavities formed by maxillary and lacrimal bones and the conchae Functions of conchae are to create swirls, turbulence, and eddies that: - direct particles against mucus - slow air movement so it can be warmed and humidified - direct air to superior nasal cavity to olfactory receptors 5 Axial Skeleton - Sinuses Sinuses are lined with mucus membranes. -

Bilateral Ossified Stylohyoid Chain

Published online: 2020-03-02 NUJHS Vol. 2, No.2, June 2012, ISSN 2249-7110 Nitte University Journal of Health Science Case Report BILATERAL OSSIFIED STYLOHYOID CHAIN - A CASE STUDY Shivarama C.H.1, Bhat Shivarama2, Radhakrishna Shetty K.3, Vikram S.4, Avadhani R.5 1PG /Tutor, 2Associate Professor, 5Professor, 3Assistant Professor, 4Assistant Professor, Department of Anatomy, Yenepoya Medical College, Yenepoya University, Mangalore - 575 018, India. Correspondence: Ramakrishna Avadhani, Mobile : 98452 53560, E-mail : [email protected] Abstract : The styloid process is a slender bony projection that arises from the inferior surface of the temporal bone just beneath the external auditory meatus and closely related to the stylomastoid foramen. The normal length of SP in an adult is considered to be 20to 30mm however, it is very variably developed, ranging in length from a few millimetres to a few centimetres. The styloid process is developed at the cranial end of cartilage in the second visceral or hyoid arch by two centers: a proximal, for the tympanohyal, appearing before birth; the other, for the distal stylohyal, after birth. But sometimes the stylohyoid chain may form, that extends between the temporal and hyoid bones which are divided into 4 sections: tympanohyal, stylohyal, ceratohyal and hypohyal. Cartilage that is embryo logically located at the stylohyoid ligament may undergo calcification of varying degrees, which causes variations. Ossified stylohyal ligament parts may merge or leave gaps in between. The anatomy of styloid process has immense embryological, clinical, surgical importance. Keywords : Styloid process, Stylohyoid chain, Reichert's cartilage, Eagle's syndrome. Introduction : crossing lateral to the process in the parotid The styloid process (SP), slender, pointed, about 2.5 cm in gland1.Normally the SP tapers toward its tip that lies in the 2 length, projects anteroinferiorly from the temporal bone's pharyngeal wall lateral to the tonsillar fossa . -

Hyoid Bone Fusion and Bone Density Across the Lifespan: Prediction of Age and Sex

Hyoid bone fusion and bone density across the lifespan: prediction of age and sex Ellie Fisher, Diane Austin, Helen M. Werner, Ying Ji Chuang, Edward Bersu & Houri K. Vorperian Forensic Science, Medicine, and Pathology ISSN 1547-769X Forensic Sci Med Pathol DOI 10.1007/s12024-016-9769-x 1 23 Your article is published under the Creative Commons Attribution license which allows users to read, copy, distribute and make derivative works, as long as the author of the original work is cited. You may self- archive this article on your own website, an institutional repository or funder’s repository and make it publicly available immediately. 1 23 Forensic Sci Med Pathol DOI 10.1007/s12024-016-9769-x ORIGINAL ARTICLE Hyoid bone fusion and bone density across the lifespan: prediction of age and sex 1 1 1 1 Ellie Fisher • Diane Austin • Helen M. Werner • Ying Ji Chuang • 2 1 Edward Bersu • Houri K. Vorperian Accepted: 7 March 2016 Ó The Author(s) 2016. This article is published with open access at Springerlink.com Abstract The hyoid bone supports the important func- predictors of age group for adult females. This study pro- tions of swallowing and speech. At birth, the hyoid bone vides a developmental baseline for understanding hyoid consists of a central body and pairs of right and left lesser bone fusion and bone density in typically developing and greater cornua. Fusion of the greater cornua with the individuals. Findings have implications for the disciplines body normally occurs in adulthood, but may not occur at of forensics, anatomy, speech pathology, and anthropology. -

Description Concept ID Synonyms Definition

Description Concept ID Synonyms Definition Category ABNORMALITIES OF TEETH 426390 Subcategory Cementum Defect 399115 Cementum aplasia 346218 Absence or paucity of cellular cementum (seen in hypophosphatasia) Cementum hypoplasia 180000 Hypocementosis Disturbance in structure of cementum, often seen in Juvenile periodontitis Florid cemento-osseous dysplasia 958771 Familial multiple cementoma; Florid osseous dysplasia Diffuse, multifocal cementosseous dysplasia Hypercementosis (Cementation 901056 Cementation hyperplasia; Cementosis; Cementum An idiopathic, non-neoplastic condition characterized by the excessive hyperplasia) hyperplasia buildup of normal cementum (calcified tissue) on the roots of one or more teeth Hypophosphatasia 976620 Hypophosphatasia mild; Phosphoethanol-aminuria Cementum defect; Autosomal recessive hereditary disease characterized by deficiency of alkaline phosphatase Odontohypophosphatasia 976622 Hypophosphatasia in which dental findings are the predominant manifestations of the disease Pulp sclerosis 179199 Dentin sclerosis Dentinal reaction to aging OR mild irritation Subcategory Dentin Defect 515523 Dentinogenesis imperfecta (Shell Teeth) 856459 Dentin, Hereditary Opalescent; Shell Teeth Dentin Defect; Autosomal dominant genetic disorder of tooth development Dentinogenesis Imperfecta - Shield I 977473 Dentin, Hereditary Opalescent; Shell Teeth Dentin Defect; Autosomal dominant genetic disorder of tooth development Dentinogenesis Imperfecta - Shield II 976722 Dentin, Hereditary Opalescent; Shell Teeth Dentin Defect;