The Communist Party in Moscow 1925-1932

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscrit has been reproduced from the microSm master. UMI films the text directly &om the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from aiy type of conq>uter printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photogr^hs, print bleedthrough, substandard margin»;, and inqnoperalignment can adversety affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed,w l Q indicate a note the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sectionssmall overlaps.with Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for aity photographs or illustrations ^>peaiing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI A Bell & Howell Information Company 300 Nonn 2eeb Road. Ann Arbor. Ml 48106-1346 USA 313.'761-4700 800.'521-0600 Order Number 9517097 Russia’s revolutionary underground: The construction of the Moscow subway, 1931—1935 Wolf, William Kenneth, Ph.D. The Ohio State University, 1994 UMI 300N.ZeebRd. -

THE GENES of HYENAS Second Revised Edition

Arif Mansourov THE GENES OF HYENAS Second Revised Edition BAKU 1994 1 Translated into English by Zia K. Neymatoulin A. Mansourov "The Genes of Hyenas" B. Sharg-Garb, 1994, 80 p. The names of those acting in this play-pamphlet are, beyond any doubt, well-known to the readers. The pro-armenian intrigues and plots carried on by its heroes against the Azerbaijani people at different times are not the author's artistic invention, but real historical facts based on documents It is very likely that having read this small-volume play-pamphlet, the reader may find it not difficult to rightly guess who pursued, when and what kind of policy against us, and probably will draw for himself an appropriate conclusion. ISBN 5-565-00135-8 © Sharg-Garb, 1994 2 The author of this play-pamphlet is Arif Enver ogly Mansourov, one of the renowned public figures, representatives of intelligentsia, who enjoys well-deserved respect and authority in our republic. While holding important managerial and public offices, he, at the same time, is actively involved in scientific, social and political journalism. He is the author of ten scientific works, as well as the book "White Spots of History and Peristroika" which was published in several languages and had a wide public response in the republic and far beyond its borders, as also of many splendid articles on social and political affairs which were taken in by the readers with great interest. Remaining true to the noble traditions of his ancestors, Arif Mansourov, one may say, occupies the first place among contemporary patrons of art in the republic. -

Iakov Chernikhov and His Time

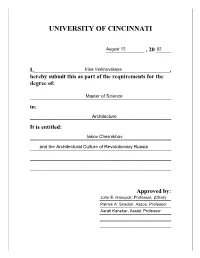

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI _____________ , 20 _____ I,______________________________________________, hereby submit this as part of the requirements for the degree of: ________________________________________________ in: ________________________________________________ It is entitled: ________________________________________________ ________________________________________________ ________________________________________________ ________________________________________________ Approved by: ________________________ ________________________ ________________________ ________________________ ________________________ IAKOV CHERNIKHOV AND THE ARCHITECTURAL CULTURE OF REVOLUTIONARY RUSSIA A thesis submitted to the Division of Research and Advanced Studies of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE IN ARCHITECTURE in the School of Architecture and Interior Design of the college of Design, Architecture, Art, and Planning 2002 by Irina Verkhovskaya Diploma in Architecture, Moscow Architectural Institute, Moscow, Russia 1999 Committee: John E. Hancock, Professor, M.Arch, Committee Chair Patrick A. Snadon, Associate Professor, Ph.D. Aarati Kanekar, Assistant Professor, Ph.D. ABSTRACT The subject of this research is the Constructivist movement that appeared in Soviet Russia in the 1920s. I will pursue the investigation by analyzing the work of the architect Iakov Chernikhov. About fifty public and industrial developments were built according to his designs during the 1920s and 1930s -

Table of Contents

Table of Contents • Abbreviations & General Notes 2 - 3 • Photographs: Flat Box Index 4 • Flat Box 1- 43 5 - 61 Description of Content • Lever Arch Files Index 62 • Lever Arch File 1- 16 63 - 100 Description of Content • Slide Box 1- 7 101 - 117 Description of Content • Photographs in Index Box 1 - 6 118 - 122 • Index Box Description of Content • Framed Photographs 123 - 124 Description of Content • Other 125 Description of Content • Publications and Articles Box 126 Description of Content Second Accession – June 2008 (additional Catherine Cooke visual material found in UL) • Flat Box 44-56 129-136 Description of Content • Postcard Box 1-6 137-156 Description of Content • Unboxed Items 158 Description of Material Abbreviations & General Notes, 2 Abbreviations & General Notes People MG = MOISEI GINZBURG NAM = MILIUTIN AMR = RODCHENKO FS = FEDOR SHEKHTEL’ AVS = SHCHUSEV VNS = SEMIONOV VET = TATLIN GWC = Gillian Wise CIOBOTARU PE= Peter EISENMANN WW= WALCOT Publications • CA- Современная Архитектура, Sovremennaia Arkhitektura • Kom.Delo – Коммунальное Дело, Kommunal’noe Delo • Tekh. Stroi. Prom- Техника Строительство и Промышленность, Tekhnika Stroitel’stvo i Promyshlennost’ • KomKh- Коммунальное Хозяство, Kommunal’noe Khoziastvo • VKKh- • StrP- Строительная Промышленность, Stroitel’naia Promyshlennost’ • StrM- Строительство Москвы, Stroitel’stvo Moskvy • AJ- The Architect’s Journal • СоРеГор- За Социалистическую Реконструкцию Городов, SoReGor • PSG- Планировка и строительство городов • BD- Building Design • Khan-Mag book- Khan-Magomedov’s -

Social & Behavioural Sciences RPTSS 2017 International

The European Proceedings of Social & Behavioural Sciences EpSBS Future Academy ISSN: 2357-1330 http://dx.doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2018.02.90 RPTSS 2017 International Conference on Research Paradigsm Transformation in Social Sciences OCTOBER REVOLUTION: LESSONS FOR RUSSIA AND THE WORLD V.V. Moiseev (a)*, V.F. Nitsevich (b), V. Ch. Guzairov (c), Zh.N. Avilova (d) *Corresponding author (a) Shukhov Belgorod State Technological University, 46 Kostyukova St., Belgorod, 308012, Russia, [email protected] (b) Moscow Automobile and Road State Technical University MADI Moscow, Russia117997, Leningrad Prospect, 64. [email protected] (c) Shukhov Belgorod State Technological University, 46 Kostyukova St., Belgorod, 308012, Russia, [email protected] (d) Belgorod State University, Russia. , 308015, Belgorod, Pobedu str, 85. [email protected] Abstract The authors analyze lessons learned and implications of events of the revolutionary year of 1917 and note that the Russian people conducted a certain selection of positive and negative consequences of the October Socialist Revolution. Unfortunately, the Russian people did not have enough free and calm time for the global analysis because for most of the post-Revolutionary period the country was at either war, or preparing for a war. Despite extreme conditions of life and acuteness of perception and assessment of the past in the collective national conscience, the Russian society seems having been succeeded in understanding the main adages and general rules of life necessary for its continuing existence with the support of its whole preceding developmental experience. Most people in Russia believe that another Socialist Revolution for Russia is contraindicated. From the historical experience, people understand that new man-made catastrophes will lead the nation and the state to demise, while modern technogenic factors may extend this process to a global scale. -

Russian Politics and Society, Second Edition

Russian politics and society ‘It should be on the shelf of anyone seeking to make heads or tails of the…problems of Yeltsin’s Russia.’ Guardian ‘The most comprehensive and detailed analysis and assessment of post-Soviet Russian politics to be found in a single volume… No student can afford to miss it.’ Peter Shearman, Journal of Area Studies Richard Sakwa’s Russian Politics and Society is the most comprehensive study of Russia’s post- communist political development. It has, since its first publication in 1993, become an indispensable guide for all those who need to know about the current political scene in Russia, about the country’s political stability and about the future of democracy under its post-communist leadership. This is the ideal introductory textbook: it covers all the key issues; it is clearly written; and it includes the most up-to-date material currently available. For this second edition, Richard Sakwa has updated the text throughout and restructured its presentation so as to emphasize the ongoing struggle for stability in Russia over the last five years. This edition includes: – the full text of the constitution of 1993 – new material on recent elections, the new parliament (State Duma and Federation Council), the development of the presidency and an evaluation of the country’s political evolution during the 1990s – up-to-date details on the development of a federal system and on local government – a thoroughly updated bibliography This new and revised edition consolidates the reputation of Russian Politics and Society as the single most comprehensive standard textbook on post-Soviet Russia. -

Culture Et Propagande Au Goulag Soviétique (1929-1953) Le Cas De La République Des Komi

Ekaterina SHEPELEVA-BOUVARD THÈSE DE DOCTORAT Soutenue le 2 juillet 2007 CULTURE ET PROPAGANDE AU GOULAG SOVIÉTIQUE (1929-1953) LE CAS DE LA RÉPUBLIQUE DES KOMI Discipline : Civilisation russe Directrice de la thèse Co-directeur de la thèse Mme. Annie ALLAIN M. Heinz -Dietrich LÖWE Université Charles de Gaulle Université Ruprecht-Karl de Lille III, France Heidelbeg, Allemagne Université Charles de Gaulle – Lille III TABLE DES MATIÈRES REMERCIEMENTS……………………………………………………………....…..…..4 AVERTISSEMENT..………………………………………….…………….…....…….5-6 AVANT-PROPOS………………………………………………………………………7-8 INTRODUCTION………………………………………………….…………...…....9-16 PARTIE I – Les camps au cœur du pays des Komi 1. En guise de géopolitique ………………………………………….…....……....…17-30 2. L’expédition Oukhtinskaia de l’OGPOU……………………...………..……....…31-44 3. L’Oukhtpetchlag……………………………………...………………….….....…..45-54 4. Les géants concentrationnaires……………………………………………….........55-68 PARTIE II – La culture derrière les barbelés : hasard historique ou directivisme soviétique ? 1. Les milieux intellectuels sous la répression………………………………....….…69-80 2. Le « camp intelligentsia »………………………………………………….............81-99 3. La culture « centralisée » et la « Ejovchtchina »………………….…….……....100-122 4. La « Jdanovchtchina » et sa portée dans les camps………..………....…..…......123-138 2 PARTIE III – L’édification culturelle : l’élément essentiel du Goulag ? 1. La KVTch et la Section politique : les enjeux idéologiques et culturels……..…139-164 2. La rééducation au Goulag : l’exemple de La Grande Petchora de Kantorovitch………. ……………………………………………………………………………………..165-185 3. Les rudiments du travail « culturo-éducatif » de la KVTch…...………………..186-203 4. Les journaux à grand tirage de la Section politique………………………….....204-214 PARTIE IV – Le miracle en pleine neige : le théâtre des « serfs » 1. Comment la vie culturelle a-t-elle émergé de l’Oukhtpetchlag?..........................215-229 2. Le théâtre de la Comédie musicale et d’Art dramatique de l’Oukhtijemlag……230-246 3. -

Sources of a Radical Mission in the Early Soviet Profession: Aleksei

1 Sources of a radical mission in the early Soviet profession Alexei Gan and the Moscow Anarchists Catherine Cooke Ten years after the 1917 revolution, there were several clearly identifiable theories of a consciously ‘revolutionary’ and ‘socialist’ architecture being practised, taught and debated in the Soviet Union. Some were purely modernist; others sought some synthesis of modernity with classicism. As soon as these various approaches start to be formulated with any rigour and launched into the public domain, we can evaluate them as more or less subtle professional responses to certain dimensions of Bolshevik ideology.1 However, preceding that stage and underpinning it was a process of personal adjustment and collective refocussing whereby a relatively conservative capitalist profession faced up to a new context and started mentally defining its tasks or writing a new narrative for its practice. This earlier part of the process, during the Civil War, is infinitely less accessible than what happened once building activity revived in 1923–4. The earliest stages of the process were also being conducted in a political environment which was very different from that of the mid-1920s, an environment that was more fluid and more plural than mainstream accounts from either East or West have suggested. In the phrase of Paul Avrich, who is one of the few (besides survivors) to insist on documenting the minority radical groups of the revolution, both Eastern and Western orthodoxies have to differing degrees been written ‘from the viewpoint of the victors’, that is privileging the Bolsheviks.2 In reality, important voices were also coming from other directions.