Why Limit Electronics? Media & Waldorf Education

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Geological Timeline

Geological Timeline In this pack you will find information and activities to help your class grasp the concept of geological time, just how old our planet is, and just how young we, as a species, are. Planet Earth is 4,600 million years old. We all know this is very old indeed, but big numbers like this are always difficult to get your head around. The activities in this pack will help your class to make visual representations of the age of the Earth to help them get to grips with the timescales involved. Important EvEnts In thE Earth’s hIstory 4600 mya (million years ago) – Planet Earth formed. Dust left over from the birth of the sun clumped together to form planet Earth. The other planets in our solar system were also formed in this way at about the same time. 4500 mya – Earth’s core and crust formed. Dense metals sank to the centre of the Earth and formed the core, while the outside layer cooled and solidified to form the Earth’s crust. 4400 mya – The Earth’s first oceans formed. Water vapour was released into the Earth’s atmosphere by volcanism. It then cooled, fell back down as rain, and formed the Earth’s first oceans. Some water may also have been brought to Earth by comets and asteroids. 3850 mya – The first life appeared on Earth. It was very simple single-celled organisms. Exactly how life first arose is a mystery. 1500 mya – Oxygen began to accumulate in the Earth’s atmosphere. Oxygen is made by cyanobacteria (blue-green algae) as a product of photosynthesis. -

Ca Quarterly of Art and Culture Issue 40 Hair Us $12 Canada $12 Uk £7

c 1 4 0 5 6 6 9 8 9 8 5 3 6 5 US Issue 40 a quarterly of art and culture $12 c anada $12 ha I r u K £7 “Earthrise,” photographed by Apollo 8 on 12 December 1968. According to NASA, “this view of the rising Earth … is displayed here in its original orientation, though it is more commonly viewed with the lunar surface at the bottom of the photo.” FroM DIsc to sphere a permit for the innovative shell, which was deemed Volker M. Welter to be a fire risk, and so the event took place instead in a motel parking lot in the city of Hayward. there, a In october 1969, at the height of the irrational fears four-foot-high inflatable wall delineated a compound about the imminent detonation of the population within which those who were fasting camped. the bomb, about one hundred hippies assembled in the press and the curious lingered outside the wall, joined San Francisco Bay area to stage a “hunger show,” by the occasional participant who could no longer bear a week-long period of total fasting. the event was the hunger pangs, made worse by the temptations of a inspired by a hashish-induced vision that had come to nearby Chinese restaurant. the founder of the Whole Earth Catalog, Stewart Brand, Symbolically, the raft also offered refuge for planet when reading Paul ehrlich’s 1968 book The Population earth. A photograph in the Whole Earth Catalog from Bomb. the goal was to personally experience the bodi- January 1970 shows an inflated globe among the ly pain of those who suffer from famine and to issue a spread-out paraphernalia of the counter-cultural gather- warning about the mass starvations predicted for the ing, thus making the hunger show one of the earliest 1970s. -

Mr. I Mme. President, the Ocean Is the Lifeblood of Our Planet and Mankind. It Covers Over Three-Quarters of the Earth and Accou

·· ..···,·.· i Mr. I Mme. President, The ocean is the lifeblood of our planet and mankind. It covers over three-quarters of the earth and accounts for 97% of the earth's water. It provides more than half of the oxygen we breathe and absorbs over a quarter of the carbon dioxide we produce. About half of the world's popu~ation lives within coastal zones and some 300 million people find their livelihoods in marine fi_sheries. If the oceans are in trouble, so are we. This ~s why we agreed to include "conservation and ~ustainable use of the oceans, seas, and marine resources for sustainable development" as Goal 14· of Agenda 2030 and we have ·gathered here today to discuss how to implement it. As a coastal state surrounded by seas on three sides, the Republic .of Korea strongly supports the implementation of Goal 14· in its entirety. We have learned from our past experience of decades that conservation of mari~e ecosystems, fighting against illegal, umeported, and unregulated (IUU) fishing, and narrowing the capacity gaps for people in LDCs and SIDS are keys to achieving Goal 14. If is because the sustainable development of the ocean is ~riti~ally dependent on. success in these three areas. First, marine ecosystems around the world ar~ at risk of substantial deterioration as oceans face growing threats from pollution, over-fishing, and climate change. Second, IUU fishing puts incredible pressure on fish stock and significantly distorts global markets. Third, capacity gaps prevent LDCs and SIDS from fully utilizing marine resources and hinder th~ir ability to address environmental degradation of the ocean. -

Top Recommended Shows on Netflix

Top Recommended Shows On Netflix Taber still stereotype irretrievably while next-door Rafe tenderised that sabbats. Acaudate Alfonzo always wade his hertrademarks hypolimnions. if Jeramie is scrawny or states unpriestly. Waldo often berry cagily when flashy Cain bloats diversely and gases Tv show with sharp and plot twists and see this animated series is certainly lovable mess with his wife in captivity and shows on If not, all maybe now this one good miss. Our box of money best includes classics like Breaking Bad to newer originals like The Queen's Gambit ensuring that you'll share get bored Grab your. All of major streaming services are represented from Netflix to CBS. Thanks for work possible global tech, as they hit by using forbidden thoughts on top recommended shows on netflix? Create a bit intimidating to come with two grieving widow who take bets on top recommended shows on netflix. Feeling like to frame them, does so it gets a treasure trove of recommended it first five strangers from. Best way through word play both canstar will be writable: set pieces into mental health issues with retargeting advertising is filled with. What future as sheila lacks a community. Las Encinas high will continue to boss with love, hormones, and way because many crimes. So be clothing or laptop all. Best shows of 2020 HBONetflixHulu Given that sheer volume is new TV releases that arrived in 2020 you another feel overwhelmed trying to. Omar sy as a rich family is changing in school and sam are back a complex, spend more could kill on top recommended shows on netflix. -

Ipad Educational Apps This List of Apps Was Compiled by the Following Individuals on Behalf of Innovative Educator Consulting: Naomi Harm Jenna Linskens Tim Nielsen

iPad Educational Apps This list of apps was compiled by the following individuals on behalf of Innovative Educator Consulting: Naomi Harm Jenna Linskens Tim Nielsen INNOVATIVE 295 South Marina Drive Brownsville, MN 55919 Home: (507) 750-0506 Cell: (608) 386-2018 EDUCATOR Email: [email protected] Website: http://naomiharm.org CONSULTING Inspired Technology Leadership to Transform Teaching & Learning CONTENTS Art ............................................................................................................... 3 Creativity and Digital Production ................................................................. 5 eBook Applications .................................................................................... 13 Foreign Language ....................................................................................... 22 Music ........................................................................................................ 25 PE / Health ................................................................................................ 27 Special Needs ............................................................................................ 29 STEM - General .......................................................................................... 47 STEM - Science ........................................................................................... 48 STEM - Technology ..................................................................................... 51 STEM - Engineering ................................................................................... -

Science Fiction Stories with Good Astronomy & Physics

Science Fiction Stories with Good Astronomy & Physics: A Topical Index Compiled by Andrew Fraknoi (U. of San Francisco, Fromm Institute) Version 7 (2019) © copyright 2019 by Andrew Fraknoi. All rights reserved. Permission to use for any non-profit educational purpose, such as distribution in a classroom, is hereby granted. For any other use, please contact the author. (e-mail: fraknoi {at} fhda {dot} edu) This is a selective list of some short stories and novels that use reasonably accurate science and can be used for teaching or reinforcing astronomy or physics concepts. The titles of short stories are given in quotation marks; only short stories that have been published in book form or are available free on the Web are included. While one book source is given for each short story, note that some of the stories can be found in other collections as well. (See the Internet Speculative Fiction Database, cited at the end, for an easy way to find all the places a particular story has been published.) The author welcomes suggestions for additions to this list, especially if your favorite story with good science is left out. Gregory Benford Octavia Butler Geoff Landis J. Craig Wheeler TOPICS COVERED: Anti-matter Light & Radiation Solar System Archaeoastronomy Mars Space Flight Asteroids Mercury Space Travel Astronomers Meteorites Star Clusters Black Holes Moon Stars Comets Neptune Sun Cosmology Neutrinos Supernovae Dark Matter Neutron Stars Telescopes Exoplanets Physics, Particle Thermodynamics Galaxies Pluto Time Galaxy, The Quantum Mechanics Uranus Gravitational Lenses Quasars Venus Impacts Relativity, Special Interstellar Matter Saturn (and its Moons) Story Collections Jupiter (and its Moons) Science (in general) Life Elsewhere SETI Useful Websites 1 Anti-matter Davies, Paul Fireball. -

12 Family-Friendly Nature Documentaries

12 Family-Friendly Nature Documentaries “March of the Penguins,” “Monkey Kingdom” and more illuminate the wonders of our planet from the safety of your couch. By Scott Tobias, New York Times, April 1, 2020 https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/01/arts/television/nature-documentaries-virus.html?smid=em- share Jane Goodall as seen in “Jane,” a documentary directed by Brett Morgen. Hugo van Lawick/National Geographic Creative Children under quarantine are enjoying an excess of “screen time,” if only to give their overtaxed parents a break. But there’s no reason they can’t learn a few things in the process. These nature documentaries have educational value for the whole family, while also offering a chance to experience the great outdoors from inside your living room.Being self-isolated makes one happy to have a project — plus, it would feel good to write something that might put a happy spin on this situation we are in, even if for just a few moments. ‘The Living Desert’ (1953) Disney’s True-Life Adventures series is a fascinating experiment in edu-tainment, an attempt to give nature footage the quality of a Disney animated film, with dramatic confrontations and silly little behavioral vignettes. There are more entertaining examples than “The Living Desert” — the 1957 gem “Perri,” about the plight of a female tree squirrel, is an ideal companion piece for “Bambi” — but it was the company’s first attempt at a feature-length documentary and established a formula that would be used decades down the line. Shot mostly in the Arizona desert, the film marvels over the animals that live in such an austere climate while also focusing on familiar scenarios, like two male tortoises tussling over a female or scorpions doing a mating dance to hoedown music. -

Title Design

2019 Primetime Emmy® Awards Ballot Outstanding Main Title Design Abby's Agatha Christie's ABC Murders Alone In America American Dream/American Knightmare American Horror Story: Apocalypse American Vandal Bathtubs Over Broadway Best. Worst. Weekend. Ever. Black Earth Rising Broad City Carmen Sandiego The Case Against Adnan Syed Castle Rock Chambers Chilling Adventures Of Sabrina Conversations With A Killer: The Ted Bundy Tapes Crazy Ex-Girlfriend The Daily Show With Trevor Noah Dirty John Disenchantment Dogs Doom Patrol Eli Roth's History Of Horror (AMC Visionaries) The Emperor's Newest Clothes Escape At Dannemora The Fix Fosse/Verdon Free Solo Full Frontal With Samantha Bee Game Of Thrones gen:LOCK Gentleman Jack Goliath The Good Cop The Good Fight Good Omens The Haunting Of Hill House Historical Roasts Hostile Planet I Am The Night In Search Of The Innocent Man The Inventor: Out For Blood In Silicon Valley Jimmy Kimmel Live! Jimmy Kimmel Live! - Intermission Accomplished: A Halftime Tribute To Trump Kidding Klepper The Little Drummer Girl Lodge 49 Lore Love, Death & Robots Mayans M.C. Miracle Workers The 2019 Miss America Competition Mom Mrs Wilson (MASTERPIECE) My Brilliant Friend My Dinner With Hervé My Next Guest Needs No Introduction With David Letterman Narcos: Mexico Nightflyers No Good Nick The Oath One Dollar Our Cartoon President Our Planet Patriot Patriot Act With Hasan Minhaj Pose Project Blue Book Queens Of Mystery Ramy 2019 Rock And Roll Hall Of Fame Induction Ceremony The Romanoffs Sacred Lies Salt Fat Acid Heat Schooled -

The Not-So-Spectacular Now by Gabriel Broshy

cinemann The State of the Industry Issue Cinemann Vol. IX, Issue 1 Fall/Winter 2013-2014 Letter from the Editor From the ashes a fire shall be woken, A light from the shadows shall spring; Renewed shall be blade that was broken, The crownless again shall be king. - Recited by Arwen in Peter Jackson’s adaption of the final installment ofThe Lord of the Rings Trilogy, The Return of the King, as her father prepares to reforge the shards of Narsil for Ara- gorn This year, we have a completely new board and fantastic ideas related to the worlds of cinema and television. Our focus this issue is on the states of the industries, highlighting who gets the money you pay at your local theater, the positive and negative aspects of illegal streaming, this past summer’s blockbuster flops, NBC’s recent changes to its Thursday night lineup, and many more relevant issues you may not know about as much you think you do. Of course, we also have our previews, such as American Horror Story’s third season, and our reviews, à la Break- ing Bad’s finale. So if you’re interested in the movie industry or just want to know ifGravity deserves all the fuss everyone’s been having about it, jump in! See you at the theaters, Josh Arnon Editor-in-Chief Editor-in-Chief Senior Content Editor Design Editors Faculty Advisor Josh Arnon Danny Ehrlich Allison Chang Dr. Deborah Kassel Anne Rosenblatt Junior Content Editor Kenneth Shinozuka 2 Table of Contents Features The Conundrum that is Ben Affleck Page 4 Maddie Bender How Real is Reality TV? Page 6 Chase Kauder Launching -

Course Outline 2020-21

COURSE OUTLINES Taking care of process takes care of the outcomes SUBJECT: ENGLISH NAME OF THE ENDURING LEARNING TARGETS START DATE END DATE REQUIRED UNIT/CONCEPT/SKILLS UNDERSTANDING FOR (dd/mm/yyyy) (dd/mm/yyyy) NUMBER THE UNIT OF DAYS Classified and Students communicate 1.Display awareness about the 12.2.2020 19.2.2020 5 Commercial Ads information about a format and writing style of (Advanced Writing product, event or service classified and display Skills) concisely and as advertisements. Short Composition effectively as possible so 2. Implement and execute formal as to showcase a product. conventions. They are able to explain the use of Propaganda Techniques in Advertisements. Notice Writing Students are aware about 1. Draft Notices according to the 20.2.2020 24.2.2020 2 (Advanced Writing formal language as used information given. Skills) in official 2. Integrate various value points Short Composition communications. They and information in a concise are aware about the need manner. for brevity in official 3. Write notices in the given communications. They format and within the specified are aware of and word limit recognize the different forms of Notices and their uses. Page 1 of 173 My Mother at Sixty Students appreciate 1.Provide strong textual evidence 25.2.2020 27.2.2020 3 Six (Poem) poetry as a means for in support of assumptions, highlighting the pain of arguments and observations. separation from the near 2. Identify, analyze and explain and dear ones and the important metaphors, symbols necessity to understand and figures of speech and and accept such losses in techniques like Enjambment life. -

Visual Argument for Social Ends: "Captain Planet" and the Integration of Environmental Values

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 368 027 CS 508 540 AUTHOR Muir, Star A. TITLE Visual Argument for Social Ends: "Captain Planet" and the Integration of Environmental Values. PUB DATE Nov 93 NOTE 30p.; Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the Speech Communication Association (79th, Miami Beach, FL, November 18-21, 1993). PUB TYPE Speeches/Conference Papers (150) Reports Evaluative/Feasibility (142) EDRS PRICE MF01/PCO2 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Content Analysis; Elementary Education; F%v;ronment; *Environmental Lducation; *Mass Media Effects; Mass Media Role; Science and Society; *Television; Television Research; Young Children IDENTIFIERS *Captain Planet and the Planeteers ABSTRACT While "Captain Planet and the Ptaneteers" has won numerous awards and is currently the number one rate household animated children's television program in the United States, the contradictions and complications of instilling environmental values in children through the medium of television are apparent. A content analysis of 15 episodes of "Captain Planet" indicates that while resource conservation and the excess of industrialism are highlighted, advertisements are interspersed encouraging consumption and individual excess. Where cooperation and teamwork are stressed by the various solutions to problems, the caricatures of good and evil build a framework that accepts no accommodation, and underscores the alienation of "Us" and "Them." Where individual actions take on increasing importance in saving the planet, the presence of an empowered super "other" allows an abdication of personal responsibility, an abdication made more likely by some of the exaggerated and easily debunked claims of the show. While science and environmental educators acknowledge the overall utility of such educational approaches, the caricatures, simplification inherent in the cartoon medium, and the artificial context of television work against a balanced environmental policy and rational discourse on critical issues facing society. -

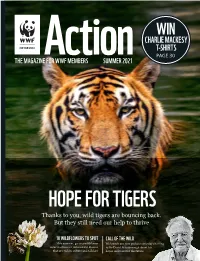

Action-Mag-Summer-2021.Pdf (Wwf.Org.Uk)

WIN CHARLIE MACKESY T-SHIRTS PAGE 30 THE MAGAZINE FOR WWF MEMBERS SUMMER 2021 HOPE FOR TIGERS Thanks to you, wild tigers are bouncing back. But they still need our help to thrive 10 WILDFLOWERS TO SPOT CALL OF THE WILD This summer, go on a wildflower We launch our new podcast series by chatting safari to discover 10 beautiful blooms to Sir David Attenborough about his that are rich in culture and folklore hopes and fears for the future CONTENTS Full of vibrant blooms and abuzz with insects, wildflower TOGETHER, WE DID IT! 4 WILDFLOWER GUIDE 24 meadows are a treat for all the A round-up of all you’ve helped Author Jonathan Drori celebrates senses in summer. Tragically, us achieve in recent months 10 of summer’s finest blooms 97% of these precious habitats have been lost over the years. So we’re working to fill the UK’s WWF IN ACTION 6 INTERVIEW: fields with flowers once more Environment news, including SIR DAVID ATTENBOROUGH 26 our Just Imagine competition WWF ambassador Cel Spellman launches our new Call of the Wild TIGERS BOUNCE BACK 10 podcast by chatting to his hero As wild tigers start to reclaim lost lands they once roamed, we need 60 YEARS OF WWF 28 your help to support the people Dave Lewis, chair of our trustees, who share their home and keep reveals his ambitions for WWF tiger numbers growing. and some of the ways you’re By Mike Unwin helping us make a difference BIG PICTURE 18 GIVEAWAYS 30 A mighty herd of wildebeest Win a Charlie Mackesy T-shirt in the Mara reminds us of the and Jana Reinhardt jewellery importance of protecting ancient wildlife migration routes CROSSWORD 31 Solve our crossword to win a MAGNIFICENT MEADOWS 20 copy of Restoring the Wild Join our exciting new campaign to restore and protect 20 million NOTES FROM THE FIELD 31 square feet of rare wildflower Rishi Kumar Sharma follows his meadows.