A Study of the Role of Krisa in the Mycenaean Era

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

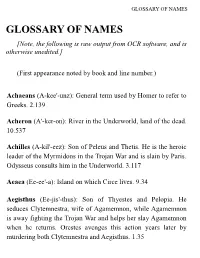

Odyssey Glossary of Names

GLOSSARY OF NAMES GLOSSARY OF NAMES [Note, the following is raw output from OCR software, and is otherwise unedited.] (First appearance noted by book and line number.) Achaeans (A-kee'-unz): General term used by Homer to reFer to Greeks. 2.139 Acheron (A'-ker-on): River in the Underworld, land of the dead. 10.537 Achilles (A-kil'-eez): Son of Peleus and Thetis. He is the heroic leader of the Myrmidons in the Trojan War and is slain by Paris. Odysseus consults him in the Underworld. 3.117 Aeaea (Ee-ee'-a): Island on which Circe lives. 9.34 Aegisthus (Ee-jis'-thus): Son of Thyestes and Pelopia. He seduces Clytemnestra, wife of Agamemnon, while Agamemnon is away fighting the Trojan War and helps her slay Agamemnon when he returns. Orestes avenges this action years later by murdering both Clytemnestra and Aegisthus. 1.35 GLOSSARY OF NAMES Aegyptus (Ee-jip'-tus): The Nile River. 4.511 Aeolus (Ee'-oh-lus): King of the island Aeolia and keeper of the winds. 10.2 Aeson (Ee'-son): Son oF Cretheus and Tyro; father of Jason, leader oF the Argonauts. 11.262 Aethon (Ee'-thon): One oF Odysseus' aliases used in his conversation with Penelope. 19.199 Agamemnon (A-ga-mem'-non): Son oF Atreus and Aerope; brother of Menelaus; husband oF Clytemnestra. He commands the Greek Forces in the Trojan War. He is killed by his wiFe and her lover when he returns home; his son, Orestes, avenges this murder. 1.36 Agelaus (A-je-lay'-us): One oF Penelope's suitors; son oF Damastor; killed by Odysseus. -

The Apotheosis of He#Rakle#S on Olympus and the Mythological Origins of the Olympics

The apotheosis of He#rakle#s on Olympus and the mythological origins of the Olympics The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Nagy, Gregory. 2019.07.12. "The apotheosis of He#rakle#s on Olympus and the mythological origins of the Olympics." Classical Inquiries. http://nrs.harvard.edu/ urn-3:hul.eresource:Classical_Inquiries. Published Version https://classical-inquiries.chs.harvard.edu/the-apotheosis-of- herakles-on-olympus-and-the-mythological-origins-of-the- olympics/ Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:41364811 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA Classical Inquiries Editors: Angelia Hanhardt and Keith Stone Consultant for Images: Jill Curry Robbins Online Consultant: Noel Spencer About Classical Inquiries (CI ) is an online, rapid-publication project of Harvard’s Center for Hellenic Studies, devoted to sharing some of the latest thinking on the ancient world with researchers and the general public. While articles archived in DASH represent the original Classical Inquiries posts, CI is intended to be an evolving project, providing a platform for public dialogue between authors and readers. Please visit http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:hul.eresource:Classical_Inquiries for the latest version of this article, which may include corrections, updates, or comments and author responses. Additionally, many of the studies published in CI will be incorporated into future CHS pub- lications. -

The Nature of Hellenistic Domestic Sculpture in Its Cultural and Spatial Contexts

THE NATURE OF HELLENISTIC DOMESTIC SCULPTURE IN ITS CULTURAL AND SPATIAL CONTEXTS DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for The Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Craig I. Hardiman, B.Comm., B.A., M.A. ***** The Ohio State University 2005 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Dr. Mark D. Fullerton, Advisor Dr. Timothy J. McNiven _______________________________ Advisor Dr. Stephen V. Tracy Graduate Program in the History of Art Copyright by Craig I. Hardiman 2005 ABSTRACT This dissertation marks the first synthetic and contextual analysis of domestic sculpture for the whole of the Hellenistic period (323 BCE – 31 BCE). Prior to this study, Hellenistic domestic sculpture had been examined from a broadly literary perspective or had been the focus of smaller regional or site-specific studies. Rather than taking any one approach, this dissertation examines both the literary testimonia and the material record in order to develop as full a picture as possible for the location, function and meaning(s) of these pieces. The study begins with a reconsideration of the literary evidence. The testimonia deal chiefly with the residences of the Hellenistic kings and their conspicuous displays of wealth in the most public rooms in the home, namely courtyards and dining rooms. Following this, the material evidence from the Greek mainland and Asia Minor is considered. The general evidence supports the literary testimonia’s location for these sculptures. In addition, several individual examples offer insights into the sophistication of domestic decorative programs among the Greeks, something usually associated with the Romans. -

A Bronze Pail of Athena Alalkomenia

A BRONZE PAIL OF ATHENA ALALKOMENIA (PLATES 31-34) T HE remarkable archaic Greek bronze vessel published here (P1. 31, a) was l.4 purchased in Mantinea in Arcadia in the spring of 1957 and donated to the Museum in Tegea where other antiquities from the same region have their abode. It had been found by a local shepherd some distance to the north of the ruins of Man- tinea but, unfortunately, the exact location of the discovery could not be ascertained.' The major part of the vessel is preserved, including about half of its upper profiled edge and one attachment for the handle which passed through its upper ring. The whole of this ring is still filled with iron and it is evident that the missing handle was made of this material. The carefully proportioned body has a height of 0.241 m. to the upper edge of the lip. Its largest diameter, 0.215 m., is slightly smaller than the total height and exactly the same both at the outer edge of the lip and at the greatest width of the body which, in turn, occurs precisely half way between that edge and the bottom of the vessel, 0.12 m. distant from both. The upper face of the lip inclines outward slightly to allow overspilling liquid to run off, as it were, from an architectural cornice. The proportion of diameter to height, the rounded bottom and the contraction of the width under the lip combine to give the impression of an elastic curvilinear rhythm to the generally ovoid form. -

Oracle of Apollo Near Oroviai (Northern Evia Island, Greece) Viewed in Its Geοlogical and Geomorphological Context, Βull

Mariolakos, E., Nicolopoulos, E., Bantekas, I., Palyvos, N., 2010, Oracles on faults: a probable location of a “lost” oracle of Apollo near Oroviai (Northern Evia Island, Greece) viewed in its geοlogical and geomorphological context, Βull. Geol. Soc. of Greece, XLIII (2), 829-844. Δελτίο της Ελληνικής Γεωλογικής Εταιρίας, 2010 Bulletin of the Geological Society of Greece, 2010 Πρακτικά 12ου Διεθνούς Συνεδρίου, Πάτρα, Μάιος 2010 Proceedings of the 12th International Congress, Patras, May, 2010 ORACLES ON FAULTS: A PROBABLE LOCATION OF A “LOST” ORACLE OF APOLLO NEAR OROVIAI (NORTHERN EUBOEA ISLAND, GREECE) VIEWED IN ITS GEOLOGICAL AND GEOMORPHOLOGICAL CONTEXT I. Mariolakos1, V. Nikolopoulos2, I. Bantekas1, N. Palyvos3 1 University of Athens, Faculty of Geology, Dynamic, Tectonic and Applied Geology Department, Panepistimioupolis Zografou, 157 84, Athens, Greece, [email protected], [email protected] 2 Ministry of Culture, 2nd Ephorate of Prehistoric and Classical Antiquities, L. Syggrou 98-100, 117 41 Athens, Greece, [email protected] 3 Harokopio university, Department of Geography, El. Venizelou 70 (part-time) / Freelance Geologist, Navarinou 21, 152 32 Halandri, Athens, Greece, [email protected] Abstract At a newly discovered archaeological site at Aghios Taxiarches in Northern Euboea, two vo- tive inscribed stelae were found in 2001 together with hellenistic pottery next to ancient wall ruins on a steep and high rocky slope. Based on the inscriptions and the geographical location of the site we propose the hypothesis that this is quite probably the spot where the oracle of “Apollo Seli- nountios” (mentioned by Strabo) would stand in antiquity. The wall ruins of the site are found on a very steep bedrock escarpment of an active fault zone, next to a hanging valley, a high waterfall and a cave. -

Download The

THE CONCEPT OF SACRED WAR IN ANCIENT GREECE By FRANCES ANNE SKOCZYLAS B.A., McGill University, 1985 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES (Department of Classics) We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA August 1987 ® Frances Anne Skoczylas, 1987 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the head of my department or by his or her representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department of CLASSICS The University of British Columbia 1956 Main Mall Vancouver, Canada V6T 1Y3 Date AUtt-UST 5r 1Q87 ii ABSTRACT This thesis will trace the origin and development of the term "Sacred War" in the corpus of extant Greek literature. This term has been commonly applied by modern scholars to four wars which took place in ancient Greece between- the sixth and fourth centuries B. C. The modern use of "the attribute "Sacred War" to refer to these four wars in particular raises two questions. First, did the ancient historians give all four of these wars the title "Sacred War?" And second, what justified the use of this title only for certain conflicts? In order to resolve the first of these questions, it is necessary to examine in what terms the ancient historians referred to these wars. -

Archaic Eretria

ARCHAIC ERETRIA This book presents for the first time a history of Eretria during the Archaic Era, the city’s most notable period of political importance. Keith Walker examines all the major elements of the city’s success. One of the key factors explored is Eretria’s role as a pioneer coloniser in both the Levant and the West— its early Aegean ‘island empire’ anticipates that of Athens by more than a century, and Eretrian shipping and trade was similarly widespread. We are shown how the strength of the navy conferred thalassocratic status on the city between 506 and 490 BC, and that the importance of its rowers (Eretria means ‘the rowing city’) probably explains the appearance of its democratic constitution. Walker dates this to the last decade of the sixth century; given the presence of Athenian political exiles there, this may well have provided a model for the later reforms of Kleisthenes in Athens. Eretria’s major, indeed dominant, role in the events of central Greece in the last half of the sixth century, and in the events of the Ionian Revolt to 490, is clearly demonstrated, and the tyranny of Diagoras (c. 538–509), perhaps the golden age of the city, is fully examined. Full documentation of literary, epigraphic and archaeological sources (most of which have previously been inaccessible to an English-speaking audience) is provided, creating a fascinating history and a valuable resource for the Greek historian. Keith Walker is a Research Associate in the Department of Classics, History and Religion at the University of New England, Armidale, Australia. -

Timeline Proposel 2013

Timeline & Games Proposal 2013 – 2016 in Greece In cooperation with Prof. Dr. Maria TZANI, Vice-President of the International Delphic Council (IDC- Berlin) for discussions with the respective Greek Ministers as well with the Greek Head of State. General Introduction Let’s meet in Greece It is the aim of the International Delphic Council to enlarge the worldwide acknowledgement of the Delphic Games of the Modern Era by restructuring the IDC in that way, that new countries have the opportunity to become a cultural hub within a region of the worldwide Delphic Games and the Delphic Movement as a whole. Summarizing the experience of the past 18 years it is of utmost importance to invite committed coun- tries protecting and strengthen (political, economical, diplomatically etc) the International Delphic Council and to support democratic development with its cultural, transparent structures. The turn around should be achieved through - moving the worldwide Delphic Head office from Germany towards Greece - establishing worldwide strong Delphic Councils at national level - the establishment of regional / continental IDC Branches, i.e. Europe, Asia, Africa, North America, South America, etc. to select appropriate and committed nations willing to set benchmarks in protecting the Delphic Games for the arts as equivalent to the Olympic Games for sports. Plans in Greece It is a target of the IDC that Greece should have a key function in the near future and that two destina- tions should be appointed in Greece for the IDC: - a larger centre in / close to Athens (reconstruction/revival of a site) - a newly constructed worldwide Delphic Centre in Delphi, at ancient times viewed as “navel of the world”, including a Temple of Fame, congress and education facilities constructed and out- lined in highest artistic architecture and art works reflecting its position as Cultural Crossroad of World Culture. -

The Thermopylae Line

CHAPTER 6 THE THERMOPYLAE LINE ENERAL Wavell arrived in Athens on the 19th April and immediately e Gheld a conference at General Wilson's quarters . Although an effectiv decision to embark the British force from Greece had been made on a higher level in London, the commanders on the spot now once agai n deeply considered the pros and cons . The Greek Government was unstable and had suggested that the British force should depart in order to avoid further devastation of the country. It was unlikely that the Greek Army of Epirus could be extricated and some of its senior officers were urging sur- render. General Wilson considered that his force could hold the Ther- mopylae line indefinitely once the troops were in position.l "The arguments in favour of fighting it out, which [it] is always better to do if possible, " wrote Wilson later,2 "were : the tying up of enemy forces, army and air , which would result therefrom ; the strain the evacuation would place o n the Navy and Merchant Marine ; the effect on the morale of the troops and the loss of equipment which would be incurred . In favour of with- drawal the arguments were : the question as to whether our forces in Greece could be reinforced as this was essential ; the question of the maintenance of our forces, plus the feeding of the civil population ; the weakness of our air forces with few airfields and little prospect of receiving reinforcements ; the little hope of the Greek Army being able to recover its morale . The decision was made to withdraw from Greece ." The British leaders con- sidered that it was unlikely that they would be able to take out any equip- ment except that which the troops carried, and that they would be lucky "to get away with 30 per cent of the force" . -

The Phocian Betrayal at Thermopylae

historia 68, 2019/4, 413–435 DOI 10.25162/historia-2019-0022 Jeffrey Rop The Phocian Betrayal at Thermopylae Abstract: This article makes three arguments regarding the Battle of Thermopylae. First, that the discovery of the Anopaea path was not dependent upon Ephialtes, but that the Persians were aware of it at their arrival and planned their attacks at Thermopylae, Artemisium, and against the Phocians accordingly. Second, that Herodotus’ claims that the failure of the Pho- cians was due to surprise, confusion, and incompetence are not convincing. And third, that the best explanation for the Phocian behavior is that they were from Delphi and betrayed their allies as part of a bid to restore local control over the sanctuary. Keywords: Thermopylae – Artemisium – Delphi – Phocis – Medism – Anopaea The courageous sacrifice of Leonidas and the Spartans is perhaps the central theme of Herodotus’ narrative and of many popular retellings of the Battle of Thermopylae in 480 BCE. Even as modern historians are appropriately more critical of this heroizing impulse, they have tended to focus their attention on issues that might explain why Leo- nidas and his men fought to the death. These include discussion of the broader strategic and tactical importance of Thermopylae, the inter-relationship and chronology of the Greek defense of the pass and the naval campaign at Artemisium, the actual number of Greeks who served under Leonidas and whether it was sufficient to hold the position, and so on. While this article inevitably touches upon some of these same topics, its main purpose is to reconsider the decisive yet often overlooked moment of the battle: the failure of the 1,000 Phocians on the Anopaea path. -

Of Greece, Its Islands

CHANDLERet al.: 255-314 - Studia dipterologica 12 (2005) Heft 2 ISSN 0945-3954 The Fungus Gnats (Diptera: Bolitophilidae, Diadocidiidae, Ditomyiidae , Keroplatidae and Mycetophilidae) of Greece, its islands and Cyprus [Die Pilzmiicken (Diptera: Bolitophilidae, Diadocidiidae, Ditomyiidae, Keroplatidae und Mycetophilidae) Griechenlands und seiner Inseln sowie Zypern4 1 by Peter J. CHANDLER, Dimitar N. BECHEV and Norbert CASPERS Mclksham (UK) Plovdiv (Bulgaria) Bechen (Gernlany) - - -. - ~ Abstract The spccics of fungu\ gnats (Bolitophilidae, Diadoc~dildae,Ditomyiidac. Keroplat~d:~eand Mycetophilidae) o~urringin Greece and Cyprus are reviewed. Altogether 201 species :Ire recorded, 189 for Greece and 69 for Cyprus. Of these 126 specie5 arc newly recorded fol. Greece and 36 arc newly recorded for Cyprus. The following new taxa arc described from Greece: Macrorrhyrtcha ibis spec. nov., M. pelargos spec. nov., M. laconica spec. nov., Macrocera critica spec. nov., Docosia cephaloniae spec. nov., D. enos spec. nov., D. pa- siphae spec. nov., Megophthalmidia illyrica spec. nov.. M. ionica spec. nov., M. pytho spec. nov., Mycomya thrakis spec. nov., Allocolocera scheria spec. nov., Sciophila pandora spec. nov., Ryrnosia labyrinthos spec. nov.; M. ill\,ric,cr is also recorded troln Croc~lia.The follow- ing ncw taa are described from Cyprus: Macrocera cypriaca spec. nov., Megophthalmidia alrzicola spec. nov., M. cedricola spec. nov. The following neu synonymies are propod: M!,c,c~r~iwrenuis I WXLKER,1856) = M. interniissa PL.ASSMA~N,l984 syn. nov., Plrror~rtr~1.illi.s- torri DLIFI>ZICKI,1889 = P rnciscr CASFERS,1991 syn. nov. A key is provided for thc western Palaearctic specie5 of M(ic-i.orrh~~~ic-IrciWI~~ERTZ. -

The Hercules Story Pdf, Epub, Ebook

THE HERCULES STORY PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Martin W. Bowman | 128 pages | 01 Aug 2009 | The History Press Ltd | 9780752450810 | English | Stroud, United Kingdom The Hercules Story PDF Book More From the Los Angeles Times. The god Apollo. Then she tried to kill the baby by sending snakes into his crib. Hercules was incredibly strong, even as a baby! When the tasks were completed, Apollo said, Hercules would become immortal. Deianira had a magic balm which a centaur had given to her. July 23, Hercules was able to drive the fearful boar into snow where he captured the boar in a net and brought the boar to Eurystheus. Greek Nyx: The Goddess of the Night. Eurystheus ordered Hercules to bring him the wild boar from the mountain of Erymanthos. Like many Greek gods, Poseidon was worshiped under many names that give insight into his importance Be on the lookout for your Britannica newsletter to get trusted stories delivered right to your inbox. Athena observed Heracles shrewdness and bravery and thus became an ally for life. The name Herakles means "glorious gift of Hera" in Greek, and that got Hera angrier still. Feb 14, Alexandra Dantzer. History at Home. Hercules was born a demi-god. On Wednesday afternoon, Sorbo retweeted a photo of some of the people who swarmed the U. Hercules could barely hear her, her whisper was that soft, yet somehow, and just as the Oracle had predicted to herself, Hera's spies discovered what the Oracle had told him. As he grew and his strength increased, Hera was evermore furious.