Annex 10: (Draft) Final Reports Template

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mannréttindaskrifstofa Íslands the Icelandic Human Rights Center

MANNRÉTTINDASKRIFSTOFA ÍSLANDS THE ICELANDIC HUMAN RIGHTS CENTER NOTES ON ICELAND’S COMBINED SEVENTEENTH AND EIGHTEENTH PERIODIC REPORTS ON IMPLEMENTATION OF THE INTERNATIONAL CONVENTION ON THE ELIMINATION OF ALL FORMS OF RACIAL DISCRIMINATION JUNE 2005 The Icelandic Human Rights Center Laugavegi 7, 3 hæð – 101 Reykjavik - Iceland Símar/Phone + 354 552 27 20 – Fax + 354 552 27 21 Netfang/ E-mail [email protected] INTRODUCTION In light of the CERD Committee’s review of Iceland’s Combined Seventeenth and Eighteenth Periodic Reports on the Implementation of the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination, which will be considered at the 67rt Session in Geneva, on 10 and 11 August 2005, the Icelandic Human Rights Center has undertaken to provide the following insights regarding Iceland’s implementation of the Convention, in co-operation with Icelandic NGOs and human rights experts. Before delving into the issues, certain factors of vital concern to the Icelandic Human Rights Center itself will be introduced. An abstract from the Center’s Report of Activities 2004 may be found in Addendum I. The Imperilled Existence of the Icelandic Human Rights Center In its Fourteenth Periodic Report on the Implementation of the Convention, the Government of Iceland referred to the establishment in 1994 of the Icelandic Human Rights Office (now Human Rights Center). The Report stated: 25. Two organizations have been established in the past two years specifically dealing with human rights. Firstly, the Human Rights Office was established in Reykjavik in the spring of 1994, similar to those which have existed in the Scandinavian countries for some time. -

Og Félagsvísindasvið Háskólinn Á Akureyri 2020

Policing Rural and Remote Areas of Iceland: Challenges and Realities of Working Outside of the Urban Centres Birta Dögg Svansdóttir Michelsen Félagsvísindadeild Hug- og félagsvísindasvið Háskólinn á Akureyri 2020 < Policing Rural and Remote Areas of Iceland: Challenges and Realities of Working Outside of the Urban Centres Birta Dögg Svansdóttir Michelsen 12 eininga lokaverkefni sem er hluti af Bachelor of Arts-prófi í lögreglu- og löggæslufræði Leiðbeinandi Andrew Paul Hill Félagsvísindadeild Hug- og félagsvísindasvið Háskólinn á Akureyri Akureyri, Maí 2020 Titill: Policing Rural and Remote Areas of Iceland Stuttur titill: Challenges and Realities of Working Outside of the Urban Centres 12 eininga lokaverkefni sem er hluti af Bachelor of Arts-prófi í lögreglu- og löggæslufræði Höfundarréttur © 2020 Birta Dögg Svansdóttir Michelsen Öll réttindi áskilin Félagsvísindadeild Hug- og félagsvísindasvið Háskólinn á Akureyri Sólborg, Norðurslóð 2 600 Akureyri Sími: 460 8000 Skráningarupplýsingar: Birta Dögg Svansdóttir Michelsen, 2020, BA-verkefni, félagsvísindadeild, hug- og félagsvísindasvið, Háskólinn á Akureyri, 39 bls. Abstract With very few exceptions, factual and fictionalized the portrayals of the police and law enforcement are almost always situated in urban settings. Only ‘real’ police work occurs in the cities while policing in rural and remote areas is often depicted as less critical, or in some cases non-existent. In a similar fashion, much of the current academic literature has focused on police work in urban environments. It is only in the past five years that the academic focus has turned its attention to the experiences of police officers who live and work in rural and remote areas. To date, no such studies have yet examined the work of police officers in rural and remote areas of Iceland. -

Expansion of Lophius Piscatorius Distribution in Iceland

Master‘s Thesis Expansion of Lophius piscatorius Distribution in Iceland: Exploring the Ecological and Economic Viability for Establishing Sustainable Monkfish Fisheries in Northwestern Iceland Rikab Rajudeen Advisor: Bjarni Jónsson University of Akureyri Faculty of Business and Science University Centre of the Westfjords Master of Resource Management: Coastal and Marine Management Ísafjörður, May 2013 Supervisory Committee Advisor: Bjarni Jónsson, MSc. Reader: Scott Heppell, Ph.D. Program Director: Dagný Arnarsdóttir, MSc. Rikab Rajudeen Expansion of Lophius piscatorius Distribution in Iceland: Exploring the Ecological and Economic Viability for Establishing Sustainable Monkfish Fisheries in Northwestern Iceland 45 ECTS thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of a Master of Resource Management degree in Coastal and Marine Management at the University Centre of the Westfjords, Suðurgata 12, 400 Ísafjörður, Iceland Degree accredited by the University of Akureyri, Faculty of Business and Science, Borgir, 600 Akureyri, Iceland Copyright © 2013 Rikab Rajudeen All rights reserved Printing: Háskólaprent, Reykjavík, June 2013 ii Declaration I hereby confirm that I am the sole author of this thesis and it is a product of my own academic research. __________________________________________ Rikab Rajudeen iii Abstract Global climate change has had profound impacts on marine ecosystems by altering physical parameters such as: ocean temperature; salinity; and hydrographic features, which largely govern species richness and distribution of fish populations. -

Conclusions of the 2020 Moving Iceland Forward Initiative

Conclusions of the 2020 – Moving Iceland Forward initiative November 2010 Conclusions of the 2020 Moving Iceland Forward initiative Compiled by the Steering Committee of the 2020 – Moving Iceland Forward Initiative Introduction Dear recipient, This report presents the principal conclusions of the vast work that has been conducted throughout the country within the framework of the 2020 - Moving Iceland Forward initiative. More than a thousand people have contributed to this project, which involved inhabitants from all over the country, representatives from independent non-profit organisations, the economy and labour market, as well as personnel from ministries and institutions, municipal authorities, regional associations, members of parliament and ministers. The workshops that were run throughout the country focused on the development of employment and economic activity and tapping the opportunities that are to be found in each region as well as the country as a whole. These meetings and the volunteer work that so many people put into them are a reflection of one of Iceland’s greatest resources and one that that will certainly prove the most effective in pulling us safely out of the recession: the people themselves. The processes and accompanying proposals contain a clear vision of the future and effective methodologies for their implementation, as well as recommendations on the key tasks to be tackled immediately. The Iceland 2020 Policy Statement and proposals have been annexed to this document as a separate file. Nothing needs to be -

Creating Institutions for Survival: Games Against Nature in Premodern Iceland

Version 1 February, 1994 Creating Institutions for Survival: Games Against Nature in Premodern Iceland I. Introduction II. Risk and institutions for survival in poor agrarian economies i. general and specific risks ii. labor contracts and risk iii. tenancy contracts iv. unexplained institutional diversity III. The choice set and sources of risk in premodern Iceland IV. Institutions for survival i. coping with specific risk: kinship and communes ii. protecting the system: population control iii. protecting the system: restricting specialization iv. system failures: drifters and beggars v. land contracts and the insurance system vi. livestock contracts and the insurance system vii. coping with general risk: the storage of food V. Storage of fodder: Institutional failure? i. background ii. centralized or decentralized storage? iii. attenuated property rights in hay reserves and livestock VI. Conclusions i. the storage puzzle ii. the system as a whole Thrainn Eggertsson Workshop in Political Theory and Policy Analysis Indiana University 513 North Park Avenue Bloomington, Indiana 47408-3895 U.S.A. Telephone: (812)855-0441 Fax: (812)855-3150 Email: [email protected] Thrainn Eggertsson February 1994 CREATING INSTITUTIONS FOR SURVIVAL: GAMES AGAINST NATURE IN PREMODERN ICELAND I. Introduction We are concerned here with the creation of non-market institutions for reducing the cost of risk in poor agrarian societies that operate at low levels of technology without the benefits of insurance, credit and other intertemporal markets. 1 Institutions, -

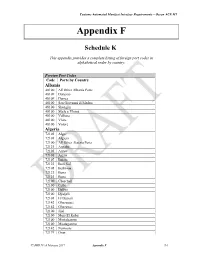

Appendix F – Schedule K

Customs Automated Manifest Interface Requirements – Ocean ACE M1 Appendix F Schedule K This appendix provides a complete listing of foreign port codes in alphabetical order by country. Foreign Port Codes Code Ports by Country Albania 48100 All Other Albania Ports 48109 Durazzo 48109 Durres 48100 San Giovanni di Medua 48100 Shengjin 48100 Skele e Vlores 48100 Vallona 48100 Vlore 48100 Volore Algeria 72101 Alger 72101 Algiers 72100 All Other Algeria Ports 72123 Annaba 72105 Arzew 72105 Arziw 72107 Bejaia 72123 Beni Saf 72105 Bethioua 72123 Bona 72123 Bone 72100 Cherchell 72100 Collo 72100 Dellys 72100 Djidjelli 72101 El Djazair 72142 Ghazaouet 72142 Ghazawet 72100 Jijel 72100 Mers El Kebir 72100 Mestghanem 72100 Mostaganem 72142 Nemours 72179 Oran CAMIR V1.4 February 2017 Appendix F F-1 Customs Automated Manifest Interface Requirements – Ocean ACE M1 72189 Skikda 72100 Tenes 72179 Wahran American Samoa 95101 Pago Pago Harbor Angola 76299 All Other Angola Ports 76299 Ambriz 76299 Benguela 76231 Cabinda 76299 Cuio 76274 Lobito 76288 Lombo 76288 Lombo Terminal 76278 Luanda 76282 Malongo Oil Terminal 76279 Namibe 76299 Novo Redondo 76283 Palanca Terminal 76288 Port Lombo 76299 Porto Alexandre 76299 Porto Amboim 76281 Soyo Oil Terminal 76281 Soyo-Quinfuquena term. 76284 Takula 76284 Takula Terminal 76299 Tombua Anguilla 24821 Anguilla 24823 Sombrero Island Antigua 24831 Parham Harbour, Antigua 24831 St. John's, Antigua Argentina 35700 Acevedo 35700 All Other Argentina Ports 35710 Bagual 35701 Bahia Blanca 35705 Buenos Aires 35703 Caleta Cordova 35703 Caleta Olivares 35703 Caleta Olivia 35711 Campana 35702 Comodoro Rivadavia 35700 Concepcion del Uruguay 35700 Diamante 35700 Ibicuy CAMIR V1.4 February 2017 Appendix F F-2 Customs Automated Manifest Interface Requirements – Ocean ACE M1 35737 La Plata 35740 Madryn 35739 Mar del Plata 35741 Necochea 35779 Pto. -

The Iceland Palaeomagnetism Database (ICEPMAG V1.0)

The Iceland Palaeomagnetism Database (ICEPMAG v1.0) Justin A. D. Tonti-Filippini FacultyFaculty of of Earth Earth Sciences Sciences UniversityUniversity of of Iceland Iceland 20182018 THE ICELAND PALAEOMAGNETISM DATABASE (ICEPMAG V1.0) Justin A. D. Tonti-Filippini 60 ECTS thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of a Magister Scientiarum degree in Geophysics Supervisor Maxwell Christopher Brown Faculty Coordinator Páll Einarsson Faculty of Earth Sciences School of Engineering and Natural Sciences University of Iceland Reykjavík, October 2018 The Iceland Palaeomagnetism Database (ICEPMAG v1.0) 60 ECTS thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of a M.Sc. degree in Geophysics Copyright © 2018 Justin A. D. Tonti-Filippini All rights reserved Faculty of Earth Sciences School of Engineering and Natural Sciences University of Iceland Sturlugata 7 101, Reykjavík, Reykjavík Iceland Telephone: 525 4000 Bibliographic information: Justin A. D. Tonti-Filippini, 2018, The Iceland Palaeomagnetism Database (ICEPMAG v1.0), M.Sc. thesis, Faculty of Earth Sciences, University of Iceland. Printing: Háskólaprent, Fálkagata 2, 107 Reykjavík Reykjavík, Iceland, October 2018 For Mary and Nicholas Abstract Iceland’s lavas preserve a unique record of Earth’s magnetic field for the past sixteen million years, and were used by early pioneers of palaeomagnetism to test several concepts which became crucial to modern geoscience. Iceland represents one of very few high latitude (>60◦) locations where long sequences of lavas suitable for palaeo- magnetic research are accessible. Since the early 1950s, research in Iceland has produced a large collection of palaeomagnetic data which has not previously been collected into a comprehensive database. ICEPMAG (http://icepmag.org/) com- piles palaeomagnetic data published in journal articles, academic theses and other databases from over 9,200 sampling sites in Iceland - one of the world’s largest col- lections of palaeomagnetic data from a single location. -

The Political Economy of Northern Regional Development

The Political Economy of Northern Regional Development Vol. I Gorm Winther, Gérard Duhaime, Jack Kruse, Chris Southcott, Hans Aage, Ivar Jonsson, Lyudmila Zalkind, Iulie Aslaksen, Solveig Glomsröd, Anne Ingeborg Myhr, Hugo Reinert, Svein Mathiesen, Erik Reinert, Joan Nymand Larsen, Rasmus Ole Rasmussen, Andrée Caron, Birger Poppel, Jón Haukur Ingimundarson (in order of appearance) TemaNord 2010:521 The Political Economy of Northern Regional Development Vol. I TemaNord 2010:521 © Nordic Council of Ministers, Copenhagen 2010 ISBN 978-92-893-2016-0 Print: Scanprint as Cover photo: Gorm Winther Copies: 430 Printed on environmentally friendly paper .This publication can be ordered on www.norden.org/order. Other Nordic publications are available at www.norden.org/publications This publication has been published with financial support by the Nordic Council of Ministers. But the con- tents of this publication do not necessarily reflect the views, policies or recommendations of the Nordic Council of Ministers. “This project was conducted as part of the International Polar Year 2007–2008, which was sponsored by the International Council for Science and the World. Meteorological Organisation. The project was cofinanced by the Commission for Social Scientific Research in Greenland, the Department for Planning, Innovation and Management, Denmarks Technical University, the Department for Environmental, Social and Spatial Change, University of Roskilde and the Department of Development and Planning, University of Aalborg.” Printed in Denmark Nordic Council of Ministers Nordic Council Store Strandstræde 18 Store Strandstræde 18 DK-1255 Copenhagen K DK-1255 Copenhagen K Phone (+45) 3396 0200 Phone (+45) 3396 0400 Fax (+45) 3396 0202 Fax (+45) 3311 1870 www.norden.org Nordic co-operation Nordic co-operation is one of the world’s most extensive forms of regional collaboration, involv- ing Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, Sweden, and three autonomous areas: the Faroe Islands, Greenland, and Åland. -

Climate Change East Iceland

Borgir v/ Norðurslóð 600 Akureyri Sími 460-8900 [email protected] http://www.rha.is Social impacts of climate change and adaptation strategies in the region of East Iceland A case study report from the ESPON project: BRIDGES – Territories with geographical specificities Hjalti Jóhannesson Senior Researcher, University of Akureyri Research Centre Grétar Þór Eyþórsson Professor in Government, University of Akureyri August 2019 R17-037-BYG © RHA-University of Akureyri Research Centre 2019 RHA-S-17-2019 ISSN 1670-8873 (web version) L-ISSN 1670-8873 (printed version) 2 1 The BRIDGES project In late 2017 the project BRIDGES – Territories with geographical specificities was granted support from the ESPON program (European Territorial Observatory Network). The final report was delivered to ESPON in April 2019 (https://www.espon.eu/geographical-specifities). The BRIDGES focuses on regions with specific territorial features who have received increasing attention in recent years, most notably in article 174 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU). The main purpose of this project is to address the opportunities and challenges of specific types of territories implies that these territories need to be considered in context rather than ‘singled out’. These types of territories constitute the main focus for this project: sparsely populated regions; mountain regions; Islands, including island- states and coastal areas. A central question is: “How can place-based, smart and integrated approaches support the challenges encountered by territories with geographic specificities”? In the project there are 15 different case study areas in Europe working with different tasks as examples of territories with geographical specificities: 1. -

Economic Effects of Tourism: Analysis at the Subnational Level in Iceland

Economic effects of tourism: Analysis at the subnational level in Iceland Lilja B. Rögnvaldsdóttir Faculty of Life and Environmental Sciences University of Iceland 2016 Economic effects of Tourism: Analysis at the sub-national level in Iceland Lilja B. Rögnvaldsdóttir 90 ECTS thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of a Magister Scientiarum degree in Tourism Studies Advisors: Cristi Frenţ Edward H. Huijbens Faculty Representative Anna Dóra Sæþórsdóttir Faculty of Life and Environmental Sciences School of Engineering and Natural Sciences University of Iceland Reykjavík, 1 June 2016 Economic Impacts of Tourism: Analysis at the sub-national level in Iceland 90 ECTS thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of a Magister Scientiarum degree in Tourism Studies Copyright © 2016 Lilja B. Rögnvaldsdóttir All rights reserved Faculty of Life and Environmental Sciences School of Engineering and Natural Sciences University of Iceland Askja Sturlugötu 7 101 Reykjavík Iceland Telephone: 525 4000 Bibliographic information: Lilja B. Rögnvaldsdóttir, 2016, Economic Impacts of Tourism: Analysis at the sub-national level in Iceland. Master’s thesis Faculty of Life and Environmental Sciences, University of Iceland, pp. 339. Reykjavík, Iceland, 1 June 2016 Abstract This study explores the availability of regional statistical data on the tourism industry in Iceland and analyses the economic effects of tourism in the Þingeyjarsýslur region. This was done by gathering regional data from fieldwork in situ consisting of company interviews and visitor surveys in Þingeyjarsýslur during the period of 2013-2015. The method used in this study considered the principles of the Nordic Model as well as the Tourism Satellite Account: Recommended Methodological Framework 2008 and its applicability at the regional level. -

Signature Redacted Institute for Data, Systems, and Society August 22, 2016

Electricity Security in a Hydro-Based Electric Power System: The Particular Case of Iceland by Shweta Mehta B.S. Civil & Environmental Engineering University of Michigan - Ann Arbor, 2009 M.S. Civil & Environmental Engineering Stanford University, 2011 SUBMITTED TO THE INSTITUTE FOR DATA, SYSTEMS, AND SOCIETY IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTERS OF SCIENCE IN TECHNOLOGY AND POLICY AT THE MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY SEPTEMBER 2016 201L6 Massachusetts Institute of Technology. All Rights Reserved. Signature of the Author: Signature redacted Institute for Data, Systems, and Society August 22, 2016 Certified By: Signature redact ed _ _ _ _ _ Ignacio Pdrez-Arriaga Visiting Professor, Sloan School of Management Thesis Co-Supervisor Certified By: - S ignature redacted Karen D Tapia-Ahumada Research Scientist, MIT Energy Initiative Thesis Co-Supervisor Certified By: Si gnature redacted Pablo Duenas-Martinez Research Scientist, MIT Energy Initiative ature redacted. Thesis Co-Supervisor Accepted By: Sigr Munther Dahleh William A. Coolidge Professor, Electrical Engineering and Computer Science Director, Institute for Data, Systems, and Society Acting Director, Technology and Policy Program MASSACHSTT ITIUTE OF TECHNOLOGY MAR 02 2017 LIBRARIES ARCHIVES 77 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02139 MITLibraries http://Iibraries.mit.edu/ask DISCLAIMER NOTICE This thesis was submitted to the Institute Archives and Special Collections without an abstract. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS These past two years at MIT have been astounding; filled with wonder, new learnings, and challenges. This is a special place, filled with even more special people who want to make the world a better place. My time here, more than ever, makes me believe that anything is possible if approached with hard work and honesty. -

Iceland IS Country Health Profile 2019 the Country Health Profile Series Contents

State of Health in the EU Iceland IS Country Health Profile 2019 The Country Health Profile series Contents The State of Health in the EU’s Country Health Profiles 1. HIGHLIGHTS 3 provide a concise and policy-relevant overview of 2. HEALTH IN ICELAND 4 health and health systems in the EU/European Economic 3. RISK FACTORS 7 Area. They emphasise the particular characteristics and challenges in each country against a backdrop of cross- 4. THE HEALTH SYSTEM 9 country comparisons. The aim is to support policymakers 5. PERFORMANCE OF THE HEALTH SYSTEM 12 and influencers with a means for mutual learning and 5.1. Effectiveness 12 voluntary exchange. 5.2. Accessibility 15 The profiles are the joint work of the OECD and the 5.3 Resilience 18 European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies, 6. KEY FINDINGS 23 in cooperation with the European Commission. The team is grateful for the valuable comments and suggestions provided by the Health Systems and Policy Monitor network, the OECD Health Committee and the EU Expert Group on Health Information. Data and information sources The calculated EU averages are weighted averages of the 28 Member States unless otherwise noted. These EU The data and information in the Country Health Profiles averages do not include Iceland and Norway. are based mainly on national official statistics provided to Eurostat and the OECD, which were validated to This profile was completed in August 2019, based on ensure the highest standards of data comparability. data available in July 2019. The sources and methods underlying these data are To download the Excel spreadsheet matching all the available in the Eurostat Database and the OECD health tables and graphs in this profile, just type the following database.