Economic Effects of Tourism: Analysis at the Subnational Level in Iceland

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Report 2007

EU_ENTWURF_08:00_ENTWURF_01 01.04.2026 13:07 Uhr Seite 1 Analyses of the European air transport market Annual Report 2007 EUROPEAN COMMISSION EU_ENTWURF_08:00_ENTWURF_01 01.04.2026 13:07 Uhr Seite 2 Air Transport and Airport Research Annual analyses of the European air transport market Annual Report 2007 German Aerospace Center Deutsches Zentrum German Aerospace für Luft- und Raumfahrt e.V. Center in the Helmholtz-Association Air Transport and Airport Research June 2008 Porz-Wahnheide Linder Höhe 51147 Köln Germany Head: Prof. Dr. Johannes Reichmuth web: http://www.dlr.de/fw Annual Report 2007 2008-06-20 Release: 1.2 Page 1 Annual analyses of the European air transport market Annual Report 2007 Document Control Information Responsible project manager: DG Energy and Transport Project task: Annual analyses of the European air transport market 2007 EC contract number: TREN/05/MD/S07.74176 Release: 1.2 Save date: 2008-06-20 Total pages: 224 Change Log Release Date Changed Pages or Chapters Comments 1.0 2008-06-06 Final Report (Annual 2007) 1.1 2008-06-09 chapter 2.1.7 PSO data update 1.2 2008-06-16 layout items 2.0 Sept 2008 full year 2007 update expected in September 2008 Disclaimer and copyright: This report has been carried out for the Directorate-General for Energy and Transport in the European Commission and expresses the opinion of the organisation undertaking the contract TREN/05/MD/S07.74176. These views have not been adopted or in any way approved by the European Commission and should not be relied upon as a statement of the European Commission's or the Transport and Energy DG's views. -

Annual Report 2007

EU_ENTWURF_08:00_ENTWURF_01 01.04.2026 13:07 Uhr Seite 1 Analyses of the European air transport market Annual Report 2007 EUROPEAN COMMISSION EU_ENTWURF_08:00_ENTWURF_01 01.04.2026 13:07 Uhr Seite 2 Air Transport and Airport Research Annual analyses of the European air transport market Annual Report 2007 German Aerospace Center Deutsches Zentrum German Aerospace für Luft- und Raumfahrt e.V. Center in the Helmholtz-Association Air Transport and Airport Research December 2008 Linder Hoehe 51147 Cologne Germany Head: Prof. Dr. Johannes Reichmuth Authors: Erik Grunewald, Amir Ayazkhani, Dr. Peter Berster, Gregor Bischoff, Prof. Dr. Hansjochen Ehmer, Dr. Marc Gelhausen, Wolfgang Grimme, Michael Hepting, Hermann Keimel, Petra Kokus, Dr. Peter Meincke, Holger Pabst, Dr. Janina Scheelhaase web: http://www.dlr.de/fw Annual Report 2007 2008-12-02 Release: 2.2 Page 1 Annual analyses of the European air transport market Annual Report 2007 Document Control Information Responsible project manager: DG Energy and Transport Project task: Annual analyses of the European air transport market 2007 EC contract number: TREN/05/MD/S07.74176 Release: 2.2 Save date: 2008-12-02 Total pages: 222 Change Log Release Date Changed Pages or Chapters Comments 1.2 2008-06-20 Final Report 2.0 2008-10-10 chapters 1,2,3 Final Report - full year 2007 draft 2.1 2008-11-20 chapters 1,2,3,5 Final updated Report 2.2 2008-12-02 all Layout items Disclaimer and copyright: This report has been carried out for the Directorate-General for Energy and Transport in the European Commission and expresses the opinion of the organisation undertaking the contract TREN/05/MD/S07.74176. -

Mannréttindaskrifstofa Íslands the Icelandic Human Rights Center

MANNRÉTTINDASKRIFSTOFA ÍSLANDS THE ICELANDIC HUMAN RIGHTS CENTER NOTES ON ICELAND’S COMBINED SEVENTEENTH AND EIGHTEENTH PERIODIC REPORTS ON IMPLEMENTATION OF THE INTERNATIONAL CONVENTION ON THE ELIMINATION OF ALL FORMS OF RACIAL DISCRIMINATION JUNE 2005 The Icelandic Human Rights Center Laugavegi 7, 3 hæð – 101 Reykjavik - Iceland Símar/Phone + 354 552 27 20 – Fax + 354 552 27 21 Netfang/ E-mail [email protected] INTRODUCTION In light of the CERD Committee’s review of Iceland’s Combined Seventeenth and Eighteenth Periodic Reports on the Implementation of the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination, which will be considered at the 67rt Session in Geneva, on 10 and 11 August 2005, the Icelandic Human Rights Center has undertaken to provide the following insights regarding Iceland’s implementation of the Convention, in co-operation with Icelandic NGOs and human rights experts. Before delving into the issues, certain factors of vital concern to the Icelandic Human Rights Center itself will be introduced. An abstract from the Center’s Report of Activities 2004 may be found in Addendum I. The Imperilled Existence of the Icelandic Human Rights Center In its Fourteenth Periodic Report on the Implementation of the Convention, the Government of Iceland referred to the establishment in 1994 of the Icelandic Human Rights Office (now Human Rights Center). The Report stated: 25. Two organizations have been established in the past two years specifically dealing with human rights. Firstly, the Human Rights Office was established in Reykjavik in the spring of 1994, similar to those which have existed in the Scandinavian countries for some time. -

Og Félagsvísindasvið Háskólinn Á Akureyri 2020

Policing Rural and Remote Areas of Iceland: Challenges and Realities of Working Outside of the Urban Centres Birta Dögg Svansdóttir Michelsen Félagsvísindadeild Hug- og félagsvísindasvið Háskólinn á Akureyri 2020 < Policing Rural and Remote Areas of Iceland: Challenges and Realities of Working Outside of the Urban Centres Birta Dögg Svansdóttir Michelsen 12 eininga lokaverkefni sem er hluti af Bachelor of Arts-prófi í lögreglu- og löggæslufræði Leiðbeinandi Andrew Paul Hill Félagsvísindadeild Hug- og félagsvísindasvið Háskólinn á Akureyri Akureyri, Maí 2020 Titill: Policing Rural and Remote Areas of Iceland Stuttur titill: Challenges and Realities of Working Outside of the Urban Centres 12 eininga lokaverkefni sem er hluti af Bachelor of Arts-prófi í lögreglu- og löggæslufræði Höfundarréttur © 2020 Birta Dögg Svansdóttir Michelsen Öll réttindi áskilin Félagsvísindadeild Hug- og félagsvísindasvið Háskólinn á Akureyri Sólborg, Norðurslóð 2 600 Akureyri Sími: 460 8000 Skráningarupplýsingar: Birta Dögg Svansdóttir Michelsen, 2020, BA-verkefni, félagsvísindadeild, hug- og félagsvísindasvið, Háskólinn á Akureyri, 39 bls. Abstract With very few exceptions, factual and fictionalized the portrayals of the police and law enforcement are almost always situated in urban settings. Only ‘real’ police work occurs in the cities while policing in rural and remote areas is often depicted as less critical, or in some cases non-existent. In a similar fashion, much of the current academic literature has focused on police work in urban environments. It is only in the past five years that the academic focus has turned its attention to the experiences of police officers who live and work in rural and remote areas. To date, no such studies have yet examined the work of police officers in rural and remote areas of Iceland. -

Expansion of Lophius Piscatorius Distribution in Iceland

Master‘s Thesis Expansion of Lophius piscatorius Distribution in Iceland: Exploring the Ecological and Economic Viability for Establishing Sustainable Monkfish Fisheries in Northwestern Iceland Rikab Rajudeen Advisor: Bjarni Jónsson University of Akureyri Faculty of Business and Science University Centre of the Westfjords Master of Resource Management: Coastal and Marine Management Ísafjörður, May 2013 Supervisory Committee Advisor: Bjarni Jónsson, MSc. Reader: Scott Heppell, Ph.D. Program Director: Dagný Arnarsdóttir, MSc. Rikab Rajudeen Expansion of Lophius piscatorius Distribution in Iceland: Exploring the Ecological and Economic Viability for Establishing Sustainable Monkfish Fisheries in Northwestern Iceland 45 ECTS thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of a Master of Resource Management degree in Coastal and Marine Management at the University Centre of the Westfjords, Suðurgata 12, 400 Ísafjörður, Iceland Degree accredited by the University of Akureyri, Faculty of Business and Science, Borgir, 600 Akureyri, Iceland Copyright © 2013 Rikab Rajudeen All rights reserved Printing: Háskólaprent, Reykjavík, June 2013 ii Declaration I hereby confirm that I am the sole author of this thesis and it is a product of my own academic research. __________________________________________ Rikab Rajudeen iii Abstract Global climate change has had profound impacts on marine ecosystems by altering physical parameters such as: ocean temperature; salinity; and hydrographic features, which largely govern species richness and distribution of fish populations. -

Conclusions of the 2020 Moving Iceland Forward Initiative

Conclusions of the 2020 – Moving Iceland Forward initiative November 2010 Conclusions of the 2020 Moving Iceland Forward initiative Compiled by the Steering Committee of the 2020 – Moving Iceland Forward Initiative Introduction Dear recipient, This report presents the principal conclusions of the vast work that has been conducted throughout the country within the framework of the 2020 - Moving Iceland Forward initiative. More than a thousand people have contributed to this project, which involved inhabitants from all over the country, representatives from independent non-profit organisations, the economy and labour market, as well as personnel from ministries and institutions, municipal authorities, regional associations, members of parliament and ministers. The workshops that were run throughout the country focused on the development of employment and economic activity and tapping the opportunities that are to be found in each region as well as the country as a whole. These meetings and the volunteer work that so many people put into them are a reflection of one of Iceland’s greatest resources and one that that will certainly prove the most effective in pulling us safely out of the recession: the people themselves. The processes and accompanying proposals contain a clear vision of the future and effective methodologies for their implementation, as well as recommendations on the key tasks to be tackled immediately. The Iceland 2020 Policy Statement and proposals have been annexed to this document as a separate file. Nothing needs to be -

The Spotter's Journal

The Spotter's Journal N° 16 – November 2007 Index Czech Airlines Airbus A321 CSA Airbus A321 1 After a long absence, Czech Airlines was back for a charter flight on 20.10 (arrival) SAS replacements 1 and 21.10 (departure). The flight from Munich (OK7162) on Saturday and back First An-124 for this Season 1 (OK7163) on Sunday was operated by an Airbus A321-200, OK-CEC. Sunday afternoon traffic 2 Commemoration Day 2 RAF Eurofighters 3 LX-LGI in new colours 3 Luxair Open Day 3 Luxembourg Movements 4 Seen at ELLX 5 © DECKER Antoine © DECKER Antoine Further SAS replacements As the SAS Dash fleet was still grounded, other aircrafts replace the daily afternoon flight to Copenhagen. On 1st October SAS arrived with an MD-83 (LN-ROS) and on 2nd October an ATR 72 from Danish Air Transport (OY-RUB) took over the flight. © THEIS Marc © THEIS Marc Danish Air Transport, OY-RUB, ATR 72 Scandinavian Airlines (SAS), LN-ROS, MD-83 First Antonov An-124 for this season IceJet VIP Dornier k k GORCZYNSKI Jace GORCZYNSKI © Jace© GORCZYNSKI In October usually the Cargo Season starts, the first This modified (extended range) Dornier 328-300, TF-NPA, flying th Antonov An-124 (Volga-Dnepr, RA-82045) for this season for IceJet arrived on 5 October 2007. This VIP Dornier has a arrived on 30th September. luxurious interior with eight club seats and six regular places. - 1 - 07.10.2007 – A busy Sunday afternoon at Luxembourg Airport Sunday afternoon a lot of different airlines were present at Luxembourg Airport. -

Creating Institutions for Survival: Games Against Nature in Premodern Iceland

Version 1 February, 1994 Creating Institutions for Survival: Games Against Nature in Premodern Iceland I. Introduction II. Risk and institutions for survival in poor agrarian economies i. general and specific risks ii. labor contracts and risk iii. tenancy contracts iv. unexplained institutional diversity III. The choice set and sources of risk in premodern Iceland IV. Institutions for survival i. coping with specific risk: kinship and communes ii. protecting the system: population control iii. protecting the system: restricting specialization iv. system failures: drifters and beggars v. land contracts and the insurance system vi. livestock contracts and the insurance system vii. coping with general risk: the storage of food V. Storage of fodder: Institutional failure? i. background ii. centralized or decentralized storage? iii. attenuated property rights in hay reserves and livestock VI. Conclusions i. the storage puzzle ii. the system as a whole Thrainn Eggertsson Workshop in Political Theory and Policy Analysis Indiana University 513 North Park Avenue Bloomington, Indiana 47408-3895 U.S.A. Telephone: (812)855-0441 Fax: (812)855-3150 Email: [email protected] Thrainn Eggertsson February 1994 CREATING INSTITUTIONS FOR SURVIVAL: GAMES AGAINST NATURE IN PREMODERN ICELAND I. Introduction We are concerned here with the creation of non-market institutions for reducing the cost of risk in poor agrarian societies that operate at low levels of technology without the benefits of insurance, credit and other intertemporal markets. 1 Institutions, -

Before the U.S. Department of Transportation Washington, D.C

BEFORE THE U.S. DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION WASHINGTON, D.C. Application of AMERICAN AIRLINES, INC. BRITISH AIRWAYS PLC OPENSKIES SAS IBERIA LÍNEAS AÉREAS DE ESPAÑA, S.A. Docket DOT-OST-2008-0252- FINNAIR OYJ AER LINGUS GROUP DAC under 49 U.S.C. §§ 41308 and 41309 for approval of and antitrust immunity for proposed joint business agreement JOINT MOTION TO AMEND ORDER 2010-7-8 FOR APPROVAL OF AND ANTITRUST IMMUNITY FOR AMENDED JOINT BUSINESS AGREEMENT Communications about this document should be addressed to: For American Airlines: For Aer Lingus, British Airways, and Stephen L. Johnson Iberia: Executive Vice President – Corporate Kenneth P. Quinn Affairs Jennifer E. Trock R. Bruce Wark Graham C. Keithley Vice President and Deputy General BAKER MCKENZIE LLP Counsel 815 Connecticut Ave. NW Robert A. Wirick Washington, DC 20006 Managing Director – Regulatory and [email protected] International Affairs [email protected] James K. Kaleigh [email protected] Senior Antitrust Attorney AMERICAN AIRLINES, INC. Laurence Gourley 4333 Amon Carter Blvd. General Counsel Fort Worth, Texas 76155 AER LINGUS GROUP DESIGNATED [email protected] ACTIVITY COMPANY (DAC) [email protected] Dublin Airport [email protected] P.O. Box 180 Dublin, Ireland Daniel M. Wall Richard Mendles Michael G. Egge General Counsel, Americas Farrell J. Malone James B. Blaney LATHAM & WATKINS LLP Senior Counsel, Americas 555 11th St., NW BRITISH AIRWAYS PLC Washington, D.C. 20004 2 Park Avenue, Suite 1100 [email protected] New York, NY 10016 [email protected] [email protected] Antonio Pimentel Alliances Director For Finnair: IBERIA LÍNEAS AÉREAS DE ESPAÑA, Sami Sareleius S.A. -

Ita Survey of International

INTERNATIONAL TRADE ADMINISTRATION OFFICE OF TRAVEL AND TOURISM INDUSTRIES SURVEY OF INTERNATIONAL AIR TRAVELERS DATA TAPE DOCUMENTATION FOR 2009 Prepared by CIC Research, Inc. August 15, 2011 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page 1. General Introduction ................................................................................................... 1 2. Variable Names in Relationship to Questionnaire ...................................................... 2 3. Variable Names and Column Layout for ASCII Format .............................................. 9 4. Valid Ranges for Questionnaire Data ......................................................................... 15 5. Codebook with Question Numbers and Code Values ................................................ 23 ii TABLE OF FILES APPENDICES ON FILE A. APPEND_A.FIL - Airline Codes B. APPEND_B.FIL - Domestic Airport Codes C. APPEND_C.FIL - Foreign Airport Codes D. APPEND_D.FIL - Foreign City/Country Codes F. APPEND_F.FIL - Hotel Codes G. APPEND_G.FIL - Domestic Attraction Codes H. APPEND_H.FIL - Port of Entry Codes J. APPEND_J.FIL - Rental Car Codes M. APPEND_M.FIL - Language of Questionnaire Codes Q. APPEND_Q.FIL - Credit Card Companies iii DATA DOCUMENTATION FOR 2001 GENERAL INTRODUCTION Welcome to an explanation of the International Trade Administration, Office of Travel and Tourism Industries' (OTTI) Survey of International Air Travelers database that you have received in an electronic format. The documentation covered in this manual describes pertinent background information needed to use the OTTI database. Materials in this documentation refer to the 2009 version of the OTTI "In-Flight" Survey used by CIC Research, Inc. starting in January 2009. Specific information includes the following sections: a copy of the questionnaire with variable names the database column layout with variable names and size ranges for questionnaire data by variable name codebook In addition to the documentation included here on paper, much of the coding information is available in ASCII files. -

Information Memorandum 14 June 2021 Disclaimer

Information Memorandum 14 June 2021 Disclaimer This Presentation has been prepared by Arctica Finance hf. (“Arctica”) at the request of Fly Play hf. (“Play”) and is being furnished by Arctica and Arion Bank hf. (“Arion”) for the sole purpose of assisting the recipient in deciding whether to proceed with further analysis of the subject matter hereof. This Presentation is for informational purposes only and shall not be construed as an offer or solicitation for the subscription or purchase or sale of any securities or financial instruments, or as an invitation, inducement or intermediation for the sale, subscription or purchase of securities or financial instruments, or form the basis of any decision to finance any transactions, or for engaging in any other transaction. Arctica and Arion and their respective employees, board members and parties connected to Arctica and Arion, may have interests relating to individual legal entities to which analysis, valuation reports and other material prepared by Arctica and Arion, may pertain. The information set out in this Presentation is considered by Arctica and Arion as reliable, but the information has not been verified by Arctica, Arion Play or any other person and may be subject to updates, completion, revision and amendment resulting in material changes to the contents of this presentation. No representation or warranty, express or implied, is or will be made by Arctica, Arion, Play or and their respective employees, board members and parties otherwise connected to Arctica, Arion and Play (the“ Related Parties”) as to the accuracy, completeness or fairness of the information or opinions contained in this Presentation and any reliance the recipient places on them will be at his own sole risk. -

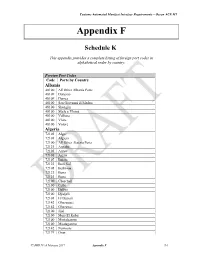

Appendix F – Schedule K

Customs Automated Manifest Interface Requirements – Ocean ACE M1 Appendix F Schedule K This appendix provides a complete listing of foreign port codes in alphabetical order by country. Foreign Port Codes Code Ports by Country Albania 48100 All Other Albania Ports 48109 Durazzo 48109 Durres 48100 San Giovanni di Medua 48100 Shengjin 48100 Skele e Vlores 48100 Vallona 48100 Vlore 48100 Volore Algeria 72101 Alger 72101 Algiers 72100 All Other Algeria Ports 72123 Annaba 72105 Arzew 72105 Arziw 72107 Bejaia 72123 Beni Saf 72105 Bethioua 72123 Bona 72123 Bone 72100 Cherchell 72100 Collo 72100 Dellys 72100 Djidjelli 72101 El Djazair 72142 Ghazaouet 72142 Ghazawet 72100 Jijel 72100 Mers El Kebir 72100 Mestghanem 72100 Mostaganem 72142 Nemours 72179 Oran CAMIR V1.4 February 2017 Appendix F F-1 Customs Automated Manifest Interface Requirements – Ocean ACE M1 72189 Skikda 72100 Tenes 72179 Wahran American Samoa 95101 Pago Pago Harbor Angola 76299 All Other Angola Ports 76299 Ambriz 76299 Benguela 76231 Cabinda 76299 Cuio 76274 Lobito 76288 Lombo 76288 Lombo Terminal 76278 Luanda 76282 Malongo Oil Terminal 76279 Namibe 76299 Novo Redondo 76283 Palanca Terminal 76288 Port Lombo 76299 Porto Alexandre 76299 Porto Amboim 76281 Soyo Oil Terminal 76281 Soyo-Quinfuquena term. 76284 Takula 76284 Takula Terminal 76299 Tombua Anguilla 24821 Anguilla 24823 Sombrero Island Antigua 24831 Parham Harbour, Antigua 24831 St. John's, Antigua Argentina 35700 Acevedo 35700 All Other Argentina Ports 35710 Bagual 35701 Bahia Blanca 35705 Buenos Aires 35703 Caleta Cordova 35703 Caleta Olivares 35703 Caleta Olivia 35711 Campana 35702 Comodoro Rivadavia 35700 Concepcion del Uruguay 35700 Diamante 35700 Ibicuy CAMIR V1.4 February 2017 Appendix F F-2 Customs Automated Manifest Interface Requirements – Ocean ACE M1 35737 La Plata 35740 Madryn 35739 Mar del Plata 35741 Necochea 35779 Pto.