The Gift of Moving: Intergenerational Consequences of a Mobility Shock

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Oaklands School Geography Department - Iceland Trip 2019

Oaklands School Geography Department - Iceland Trip 2019 Skogafoss Waterfall Name: __________________________________ Tutor Group: _____________________________ 1 Part A: Where is Iceland? Iceland is an island formerly belonging to Denmark. It has been a Republic since 1944 and is found in the middle of the North Atlantic Ocean. We will fly to Keflavik and stay near Hvolsvollur in the SW of the island. The map above is an enlargement of the box drawn on the map of Iceland below left. Map area on next Clearly, we are only visiting a small section of page the island, but in this small area you will be blown away by what you will see. Perhaps your visit to the island will prompt you to come back to explore further in the future? 2 Part B: History of Iceland Iceland is only about 20 million years old! It was formed by a series of volcanic eruptions at the Mid- Atlantic ridge. In fact the plume of magma called the Iceland ‘Hot Spot’ is responsible for its continued existence and almost continuous volcanic activity. Exact dates for first human occupancy is uncertain, but the accepted date is 874 for the first permanent settlers from Scandinavia. They settled near Reykjavik (which means ‘smokey cove’ – due to the Geothermal heat). Settlers continued to come from Norway, Scotland and Ireland. The first parliament was held at Thingvellir (pictured right), where chieftains met and agreed laws and rules for the country. The country converted to Christianity in the 11th Century, but pagan worship was tolerated if it was in secret. Civil war followed and the end result was that Iceland accepted Norwegian sovereignty and were ruled by the Norwegian kings. -

COURSE NOTES V0

Sheep in the Land of Fire and Ice Sauðfé í landi elds og ísa COURSE NOTES v0 Sheep in the land of Fire and Ice COURSE NOTES v0 Contents PART 1. COURSE INTRODUCTION SECTION 1.1 SHEEP IN THE LAND OF FIRE AND ICE About this course Meet the experts Navigating the course PART 2. SHEEP GRAZING IN THE NORTH SECTION 2.1 SHEEP GRAZING IN THE NORTH Grazing in Nordic regions Studying herbivory in the North – the need for coordinated research efforts SECTION 2.2 SHEEP GRAZING IN ICELAND Environmental conditions in Iceland How do these conditions influence the impacts of grazing? SECTION 2.3 SHEEP GRAZING CAN LEAD TO SOIL EROSION PART 3. HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE OF SHEEP GRAZING IN ICELAND SECTION 3.1 ICELAND BEFORE SHEEP What Iceland could have looked like before human settlement SECTION 3.2 MODELLING THE ECOSYSTEM State and transition models SECTION 3.3 THEN, SHEEP ARRIVED Sheep over time: from landnám to our days SECTION 3.4 EFFORTS TO MITIGATE ENVIRONMENTAL DEGRADATION PART 4. THE PRESENT AND THE FUTURE OF SHEEP GRAZING IN ICELAND SECTION 4.1 SHEEP IN ICELAND TODAY Current grazing systems in Iceland SECTION 4.2 CURRENT EFFORTS IN ECOLOGICAL RESEARCH Grazing research SECTION 4.3 SUSTAINABLE SHEEP GRAZING? The future of sheep grazing PART 5. SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS SECTION 5.1 SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS USEFUL LINKS REFERENCES 2 Sheep in the land of Fire and Ice COURSE NOTES v0 Part 1. Course introduction Section 1.1 Sheep in the Land of Fire and Ice About this course Sheep in the Land of Fire and Ice is a short Massive Open Online Course (MOOC) about sheep grazing in Iceland. -

Mannréttindaskrifstofa Íslands the Icelandic Human Rights Center

MANNRÉTTINDASKRIFSTOFA ÍSLANDS THE ICELANDIC HUMAN RIGHTS CENTER NOTES ON ICELAND’S COMBINED SEVENTEENTH AND EIGHTEENTH PERIODIC REPORTS ON IMPLEMENTATION OF THE INTERNATIONAL CONVENTION ON THE ELIMINATION OF ALL FORMS OF RACIAL DISCRIMINATION JUNE 2005 The Icelandic Human Rights Center Laugavegi 7, 3 hæð – 101 Reykjavik - Iceland Símar/Phone + 354 552 27 20 – Fax + 354 552 27 21 Netfang/ E-mail [email protected] INTRODUCTION In light of the CERD Committee’s review of Iceland’s Combined Seventeenth and Eighteenth Periodic Reports on the Implementation of the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination, which will be considered at the 67rt Session in Geneva, on 10 and 11 August 2005, the Icelandic Human Rights Center has undertaken to provide the following insights regarding Iceland’s implementation of the Convention, in co-operation with Icelandic NGOs and human rights experts. Before delving into the issues, certain factors of vital concern to the Icelandic Human Rights Center itself will be introduced. An abstract from the Center’s Report of Activities 2004 may be found in Addendum I. The Imperilled Existence of the Icelandic Human Rights Center In its Fourteenth Periodic Report on the Implementation of the Convention, the Government of Iceland referred to the establishment in 1994 of the Icelandic Human Rights Office (now Human Rights Center). The Report stated: 25. Two organizations have been established in the past two years specifically dealing with human rights. Firstly, the Human Rights Office was established in Reykjavik in the spring of 1994, similar to those which have existed in the Scandinavian countries for some time. -

Og Félagsvísindasvið Háskólinn Á Akureyri 2020

Policing Rural and Remote Areas of Iceland: Challenges and Realities of Working Outside of the Urban Centres Birta Dögg Svansdóttir Michelsen Félagsvísindadeild Hug- og félagsvísindasvið Háskólinn á Akureyri 2020 < Policing Rural and Remote Areas of Iceland: Challenges and Realities of Working Outside of the Urban Centres Birta Dögg Svansdóttir Michelsen 12 eininga lokaverkefni sem er hluti af Bachelor of Arts-prófi í lögreglu- og löggæslufræði Leiðbeinandi Andrew Paul Hill Félagsvísindadeild Hug- og félagsvísindasvið Háskólinn á Akureyri Akureyri, Maí 2020 Titill: Policing Rural and Remote Areas of Iceland Stuttur titill: Challenges and Realities of Working Outside of the Urban Centres 12 eininga lokaverkefni sem er hluti af Bachelor of Arts-prófi í lögreglu- og löggæslufræði Höfundarréttur © 2020 Birta Dögg Svansdóttir Michelsen Öll réttindi áskilin Félagsvísindadeild Hug- og félagsvísindasvið Háskólinn á Akureyri Sólborg, Norðurslóð 2 600 Akureyri Sími: 460 8000 Skráningarupplýsingar: Birta Dögg Svansdóttir Michelsen, 2020, BA-verkefni, félagsvísindadeild, hug- og félagsvísindasvið, Háskólinn á Akureyri, 39 bls. Abstract With very few exceptions, factual and fictionalized the portrayals of the police and law enforcement are almost always situated in urban settings. Only ‘real’ police work occurs in the cities while policing in rural and remote areas is often depicted as less critical, or in some cases non-existent. In a similar fashion, much of the current academic literature has focused on police work in urban environments. It is only in the past five years that the academic focus has turned its attention to the experiences of police officers who live and work in rural and remote areas. To date, no such studies have yet examined the work of police officers in rural and remote areas of Iceland. -

Expansion of Lophius Piscatorius Distribution in Iceland

Master‘s Thesis Expansion of Lophius piscatorius Distribution in Iceland: Exploring the Ecological and Economic Viability for Establishing Sustainable Monkfish Fisheries in Northwestern Iceland Rikab Rajudeen Advisor: Bjarni Jónsson University of Akureyri Faculty of Business and Science University Centre of the Westfjords Master of Resource Management: Coastal and Marine Management Ísafjörður, May 2013 Supervisory Committee Advisor: Bjarni Jónsson, MSc. Reader: Scott Heppell, Ph.D. Program Director: Dagný Arnarsdóttir, MSc. Rikab Rajudeen Expansion of Lophius piscatorius Distribution in Iceland: Exploring the Ecological and Economic Viability for Establishing Sustainable Monkfish Fisheries in Northwestern Iceland 45 ECTS thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of a Master of Resource Management degree in Coastal and Marine Management at the University Centre of the Westfjords, Suðurgata 12, 400 Ísafjörður, Iceland Degree accredited by the University of Akureyri, Faculty of Business and Science, Borgir, 600 Akureyri, Iceland Copyright © 2013 Rikab Rajudeen All rights reserved Printing: Háskólaprent, Reykjavík, June 2013 ii Declaration I hereby confirm that I am the sole author of this thesis and it is a product of my own academic research. __________________________________________ Rikab Rajudeen iii Abstract Global climate change has had profound impacts on marine ecosystems by altering physical parameters such as: ocean temperature; salinity; and hydrographic features, which largely govern species richness and distribution of fish populations. -

The 2010 Eyjafjallajökull Summit Eruption: Nature of the Explosive Activity in the Initial Phase

The 2010 Eyjafjallajökull summit eruption: Nature of the explosive activity in the initial phase Elísabet Pálmadóttir Faculty of Earth science University of Iceland 2016 The 2010 Eyjafjallajökull summit eruption: Nature of the explosive activity in the initial phase Elísabet Pálmadóttir 60 ECTS thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of a Magister Scientiarum degree in Geology Advisor Professor Þorvaldur Þórðarson External Examiner Lucia Gurioli M.Sc. committee Professor Þorvaldur Þórðarson Professor Bruce F. Houghton Faculty of Earth Sciences School of Engineering and Natural Sciences University of Iceland Reykjavík, 29 May 2016 The 2010 Eyjafjallajökull summit eruption: Nature of explosive activity in the initial phase Explosive activity in Eyjafjallajökull 2010 event 60 ECTS thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of a Magister Scientiarum degree in Geology Copyright © 2016 Elísabet Pálmadóttir All rights reserved Faculty of Earth Sciences School of Engineering and Natural Sciences University of Iceland Sturlugata 7. Askja 101, Reykjavik Iceland Telephone: 525 4000 Bibliographic information: Elísabet Pálmadóttir, 2016, The 2010 Eyjafjallajökull summit eruption: Nature of explosive activity in the initial phase, Master’s thesis, Faculty of Earth Sciences, University of Iceland. ISBN Printing: Háskólaprent, Fálkagata 2, 107 Reykjavík Reykjavík, Iceland, 6th month 2016 Abstract On 14 April 2010 the summit of Eyjafjallajökull started to erupt, following an effusive eruption at the volcanoes flank. This was a hybrid eruption that featured pulsating explosive activity along with lava effusion. On 17 April 2010, which is the focus of this study, the magma discharge rate was estimated around 6.0 x 105 kg s-1 with a plume reaching over 9 km. Plume monitoring covering seven hours of the afternoon on the 17th, revealed eight distinct pulsating periods of dark explosive plume pulses, following periods of little or no activity. -

Conclusions of the 2020 Moving Iceland Forward Initiative

Conclusions of the 2020 – Moving Iceland Forward initiative November 2010 Conclusions of the 2020 Moving Iceland Forward initiative Compiled by the Steering Committee of the 2020 – Moving Iceland Forward Initiative Introduction Dear recipient, This report presents the principal conclusions of the vast work that has been conducted throughout the country within the framework of the 2020 - Moving Iceland Forward initiative. More than a thousand people have contributed to this project, which involved inhabitants from all over the country, representatives from independent non-profit organisations, the economy and labour market, as well as personnel from ministries and institutions, municipal authorities, regional associations, members of parliament and ministers. The workshops that were run throughout the country focused on the development of employment and economic activity and tapping the opportunities that are to be found in each region as well as the country as a whole. These meetings and the volunteer work that so many people put into them are a reflection of one of Iceland’s greatest resources and one that that will certainly prove the most effective in pulling us safely out of the recession: the people themselves. The processes and accompanying proposals contain a clear vision of the future and effective methodologies for their implementation, as well as recommendations on the key tasks to be tackled immediately. The Iceland 2020 Policy Statement and proposals have been annexed to this document as a separate file. Nothing needs to be -

University Microfilms International 300 N

VOLCANO-ICE INTERACTIONS ON THE EARTH AND MARS Item Type text; Dissertation-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Allen, Carlton Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 04/10/2021 05:22:59 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/298515 INFORMATION TO USERS This was produced from a copy of a document sent to us for microfilming. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting through an image and duplicating adjacent pages to assure you of complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a round black mark it is an indication that the film inspector noticed either blurred copy because of movement during exposure, or duplicate copy. Unless we meant to delete copyrighted materials that should not have been filmed, you will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. -

Creating Institutions for Survival: Games Against Nature in Premodern Iceland

Version 1 February, 1994 Creating Institutions for Survival: Games Against Nature in Premodern Iceland I. Introduction II. Risk and institutions for survival in poor agrarian economies i. general and specific risks ii. labor contracts and risk iii. tenancy contracts iv. unexplained institutional diversity III. The choice set and sources of risk in premodern Iceland IV. Institutions for survival i. coping with specific risk: kinship and communes ii. protecting the system: population control iii. protecting the system: restricting specialization iv. system failures: drifters and beggars v. land contracts and the insurance system vi. livestock contracts and the insurance system vii. coping with general risk: the storage of food V. Storage of fodder: Institutional failure? i. background ii. centralized or decentralized storage? iii. attenuated property rights in hay reserves and livestock VI. Conclusions i. the storage puzzle ii. the system as a whole Thrainn Eggertsson Workshop in Political Theory and Policy Analysis Indiana University 513 North Park Avenue Bloomington, Indiana 47408-3895 U.S.A. Telephone: (812)855-0441 Fax: (812)855-3150 Email: [email protected] Thrainn Eggertsson February 1994 CREATING INSTITUTIONS FOR SURVIVAL: GAMES AGAINST NATURE IN PREMODERN ICELAND I. Introduction We are concerned here with the creation of non-market institutions for reducing the cost of risk in poor agrarian societies that operate at low levels of technology without the benefits of insurance, credit and other intertemporal markets. 1 Institutions, -

Iceland - Land of Fire and Ice Wagner Days in Reykjavik

Iceland - Land of Fire and Ice Wagner Days in Reykjavik Day 1: Keflavik SERVICES: Individual flight to Keflavik and accomodation in the booked. Hotel. Dinner in a typical restaurant. Day 2: Day trip Golden Circle • 5xaccommodation/breakfast A day trip leads to the well-known attractions along the "Golden Circle". -buffet in 4-star hotel The first stop is in the Thingvellir National Park, a UNESCO World "Reykjavik Downtown" or in Heritage Site and a geologically unique place on Earth. We continue to the 3-star hotel "Fosshotel the geyser geothermal area, where the active spring source Strokkur Baron" hurls a column of steam and water into the sky. Not far away, the • Excursions and visits "golden waterfall" Gullfoss plunges impressively over two steps into a according to the program deep canyon. Through the fertile landscape of Southern Iceland we go • 1 first cat. ticket for back to Reykjavik. In the evening you will experience a piano concerto "The Valkyrie" • organized by the Richard Wagner Association Island. Participation in the Wagner Symposium Day 3: Wagner Lectures - City Tour • Piano Recital In the morning, he participated in the Richard Wagner Symposium • Concert in the church of organized by Wagner Verband Island. In the afternoon we start our city Reykholt tour in Reykjavik. Highlights include the new concert hall "Harpa", the • 2 dinners according to the old town, parliament, town hall, the port, the university and the two program landmarks of Reykjavik: the glass dome Perlan "the pearl" and the • English speaking local tour church Hallgrimskirkja.At 6.30 p.m. Visit to the semi-concert guide performance of Wagner's "Die Walküre" at the Harpa Concerthall. -

INTERNAL DOCUMENT IALUATION of WESTERN SPECULATIVE SEISMIC SURVEY OFF N. ICELAND (WESTERN GEOPHYSICAL) D.G. Roberts

INTERNAL DOCUMENT IALUATION OF WESTERN SPECULATIVE SEISMIC SURVEY OFF N. ICELAND (WESTERN GEOPHYSICAL) D.G. Roberts [This document should not be cited in a published bibliography, and is supplied for the use of the recipient only]. INSTITUTE OF OCEAN OCR APHIC SCIENCES INSTITUTE OF OCEANOGRAPHIC SCIENCES Wormley, Godalming, Surrey, GU8 SUB. (042-879-4141) (Director: Dr. A. S. Laughton) Bidston Observatory, Crossway, Birkenhead, Taunton, Merseyside, L43 7RA. Somerset, TA1 2DW. (051-652-2396) (0823-86211) (Assistant Director: Dr. D. E. Cartwright) (Assistant Director: M.J. Tucker) EVALUATION OF WESTERN SPECULATIVE SEISMIC SURVEY OFF N. ICELAND (WESTERN GEOPHYSICAL) D.G. Roberts Internal Document No. 69 1. Background During November 1976 Western Geophysical Corporation made a small (852 km) speculative seismic survey of the insular shelf and slope off Northern Iceland (Fig. 1). The Dept. of Energy had previously suggested that lOS investigate the survey with a view to purchase. This was done in August and Roberts subsequently reported verbally to Scott that there would be little point in purchasing the survey in view of its location astride the axis of the mid-ocean ridge north of Iceland. Subsequently papers have been circulated by Richard and Garthwaite of CIP to Shell, BNOC, BGC, BP and others reporting the views of Nordahl (Chairman, Central Bank of Iceland) that 'there is section and structure no great distance offshore.' G. Dodsworth of Western recently presented a short paper on the data at the Tromso meeting. No interpretation report exists, however. This report briefly evaluates the seismic survey and comments on its usefulness. 2. Data The data were acquired from M.V. -

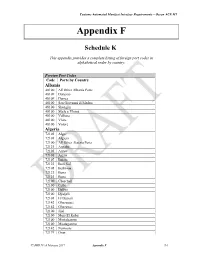

Appendix F – Schedule K

Customs Automated Manifest Interface Requirements – Ocean ACE M1 Appendix F Schedule K This appendix provides a complete listing of foreign port codes in alphabetical order by country. Foreign Port Codes Code Ports by Country Albania 48100 All Other Albania Ports 48109 Durazzo 48109 Durres 48100 San Giovanni di Medua 48100 Shengjin 48100 Skele e Vlores 48100 Vallona 48100 Vlore 48100 Volore Algeria 72101 Alger 72101 Algiers 72100 All Other Algeria Ports 72123 Annaba 72105 Arzew 72105 Arziw 72107 Bejaia 72123 Beni Saf 72105 Bethioua 72123 Bona 72123 Bone 72100 Cherchell 72100 Collo 72100 Dellys 72100 Djidjelli 72101 El Djazair 72142 Ghazaouet 72142 Ghazawet 72100 Jijel 72100 Mers El Kebir 72100 Mestghanem 72100 Mostaganem 72142 Nemours 72179 Oran CAMIR V1.4 February 2017 Appendix F F-1 Customs Automated Manifest Interface Requirements – Ocean ACE M1 72189 Skikda 72100 Tenes 72179 Wahran American Samoa 95101 Pago Pago Harbor Angola 76299 All Other Angola Ports 76299 Ambriz 76299 Benguela 76231 Cabinda 76299 Cuio 76274 Lobito 76288 Lombo 76288 Lombo Terminal 76278 Luanda 76282 Malongo Oil Terminal 76279 Namibe 76299 Novo Redondo 76283 Palanca Terminal 76288 Port Lombo 76299 Porto Alexandre 76299 Porto Amboim 76281 Soyo Oil Terminal 76281 Soyo-Quinfuquena term. 76284 Takula 76284 Takula Terminal 76299 Tombua Anguilla 24821 Anguilla 24823 Sombrero Island Antigua 24831 Parham Harbour, Antigua 24831 St. John's, Antigua Argentina 35700 Acevedo 35700 All Other Argentina Ports 35710 Bagual 35701 Bahia Blanca 35705 Buenos Aires 35703 Caleta Cordova 35703 Caleta Olivares 35703 Caleta Olivia 35711 Campana 35702 Comodoro Rivadavia 35700 Concepcion del Uruguay 35700 Diamante 35700 Ibicuy CAMIR V1.4 February 2017 Appendix F F-2 Customs Automated Manifest Interface Requirements – Ocean ACE M1 35737 La Plata 35740 Madryn 35739 Mar del Plata 35741 Necochea 35779 Pto.