Notes on the Nominal System of Bashkardi Agnes Korn

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Iran's Sunnis Resist Extremism, but for How Long?

Atlantic Council SOUTH ASIA CENTER ISSUE BRIEF Iran’s Sunnis Resist Extremism, but for How Long? APRIL 2018 SCHEHEREZADE FARAMARZI ome fifteen million of Iran’s eighty million people are Sunni Muslims, the country’s largest religious minority. Politically and economically disadvantaged, these Sunnis receive relatively lit- tle attention compared with other minorities and are concen- Strated in border areas from Baluchistan in the southeast, to Kurdistan in the northwest, to the Persian Gulf in the south. The flare up of tensions between regional rivals Saudi Arabia and Iran over Lebanon, Syria, Iraq, and Yemen would seem to encourage interest in the state of Iranian Sunnis, if only because the Saudis present them- selves as defenders of the world’s Sunnis, and Iran the self-appointed champion of the Shia cause. So how do Iran’s Sunnis fare in a state where Shia theology governs al- most every aspect of life? How have they been affected by this regional rivalry? Are they stuck between jihadist and other extreme regional Sunni movements on the one hand, and the Shia regime’s aggres- sive policies on the other? Is there a danger that these policies could push some disgruntled Iranian Sunnis toward militancy and terrorism? A tour of Turkmen Sahra in the northeast of Iran near the Caspian Sea, and in Hormozgan on the Persian Gulf in 2015 and 2016 revealed some of the answers. More recent interviews were conducted by phone and in person in the United Arab Emirates (UAE) and with European-based experts. “Being a Sunni in Iran means pain, fear, anxiety, restrictions,”1 said a young The Atlantic Council’s South woman in a southern Hormozgan village. -

Thesis Development of an Optimum Framework For

THESIS DEVELOPMENT OF AN OPTIMUM FRAMEWORK FOR LARGE DAMS IMPACT ON POVERTY ALLEVIATION IN ARID REGIONS THROUGH SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT Submitted By ALI ASGHAR IRAJPOOR (2004-Ph.D-CEWRE-01) For The Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN WATER RESORECES ENGINEERING CENTRE OF EXCELLENCE IN WATER RESOURCES ENGINEERING University of Engineering & Technology, Lahore 2010 i DEVELOPMENT OF AN OPTIMUM FRAMEWORK FOR LARGE DAMS IMPACTS ON POVERTY ALLEVIATION IN ARID REGIONS THROUGH SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT By: Ali Asghar Irajpoor (2004-Ph.D-CEWRE-01) A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN WATER RESOURCES ENGINEERING Thesis Examination Date: February 6, 2010 Prof. Dr. Muhammad Latif Dr. Muhammad Munir Babar Research Advisor/ External Examiner / Professor Internal Examiner Department of Civil Engineering, Mehran University of Engineering and Technology, Jamshoro ______________________ (Prof. Dr. Muhammad Latif) DIRECTOR Thesis submitted on:____________________ CENTRE OF EXCELLENCE IN WATER RESOURCES ENGINEERING University of Engineering and Technology, Lahore 2010 ii This thesis was evaluated by the following Examiners: External Examiners: From Abroad: i) Dr. Sebastian Palt, Senior Project Manager, International Development, Ludmillastrasse 4, 84034 Landshut, Germany Ph.No. +49-871-4303279 E-mail:[email protected] ii) Dr. Riasat Ali, Group Leader, Groundwater Hydrology, Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organization (CSIRO), Land and Water, Private Bag 5 Wembley WA6913, Australia Ph. No. 08-9333-6329 E-mail: [email protected] From Pakistan: Dr. M. Munir Babar, Professor, Institute of Irrigation & Drainage Engineering, Deptt. Of Civil Engineering, Mehran University of Engineering and Technology, Jamshoro Ph. No. 0222-771226 E-mail: [email protected] Internal Examiner: Prof. -

Article 515337 3Ff1818c4e1e8d

ﻓﺼﻠﻨﺎﻣﻪ ﺗﺨﺼﺼﻲ ﺗﺤﻘﻴﻘﺎت ﺣﺸﺮه ﺷﻨﺎﺳﻲ ﺟﻠﺪ 1 ، ﺷﻤﺎره 3 ، ﺳﺎل 1388 (، -185 195 ) داﻧﺸﮕﺎه آزاد اﺳﻼﻣﻲ، واﺣﺪ اراك ﻓﺼﻠﻨﺎﻣﻪ ﺗﺨ ﺼﺼﻲ ﺗﺤﻘﻴﻘﺎت ﺣﺸﺮه ﺷﻨﺎﺳﻲ ﺷﺎﭘﺎ -4668 2008 http://jer.entomology.ir ﺟﻠﺪ 1 ، ﺷﻤﺎره 3 ، ﺳﺎل 1388 (، -185 195) ﺷﻨﺎﺳﺎﻳﻲ دﺷﻤﻨﺎن ﻃﺒﻴﻌﻲ ﭘﺴﻴﻞ آﺳﻴﺎﻳﻲ ﻣﺮﻛﺒﺎت Diaphorina citri Kuwayama (Hem., Psyllidae) در اﺳﺘﺎن ﻫﺮﻣﺰﮔﺎن ٢ ٣ ﻣﺎﻫﺮخ ﺣﺴﻦ ﭘﻮر1* ، ﻋﻠﻲ اﺻﻐﺮ ﻃﺎﻟﺒﻲ ، اﺣﺴﺎن رﺧﺸﺎﻧﻲ ، ﻋﻠﻲ ﻋﺎﻣﺮي ﺳﻴﺎﻫﻮﻳﻲ4 -1 ﺳﺎزﻣﺎن ﺟﻬﺎد ﻛﺸﺎورزي، ﻗﺮﻧﻄﻴﻨﻪ ﻧﺒﺎﺗﻲ ﺑﻨﺪر ﻟﻨﮕﻪ ، ﺑﻨﺪ ر ﻟﻨﮕﻪ -2 ﮔﺮوه ﮔﻴﺎه ﭘﺰﺷﻜﻲ، داﻧ ﺸﻜﺪه ﻛﺸﺎورزي، داﻧﺸﮕﺎه ﺗﺮﺑﻴﺖ ﻣﺪرس، ﺗﻬﺮان -3 ﮔﺮوه ﮔﻴﺎه ﭘﺰﺷﻜﻲ، داﻧﺸﻜﺪه ﻛﺸﺎورزي، داﻧﺸﮕﺎه زاﺑﻞ ، زاﺑﻞ -4 ﺳﺎزﻣﺎن ﺟﻬﺎد ﻛﺸﺎورزي ﻫﺮﻣﺰﮔﺎن، اداره ﺣﻔﻆ ﻧﺒﺎﺗﺎت ، ﻫﺮﻣﺰﮔﺎن ﭼﻜﻴﺪه ﭘﺴﻴﻞ آﺳﻴﺎﻳﻲ ﻣﺮﻛﺒﺎت، Diaphorina citri ﻳﻜﻲ از ﻣﻬﻢ ﺗﺮﻳﻦ آﻓﺎت ﻣﺮﻛﺒﺎت در ﻛﺸﻮرﻫﺎي ﺟﻨﻮب آﺳﻴﺎ اﺳﺖ . در اﻳﺮان، اﻳﻦ آﻓﺖ در اﺳﺘﺎن ﻫﺎي ﻫﺮﻣﺰﮔﺎن، ﺳﻴﺴﺘﺎنو ﺑﻠﻮﭼﺴﺘﺎن و ﻛﺮﻣﺎن ﮔﺴﺘﺮش داﺷﺘﻪ و از ﻃﺮﻳﻖ ﻣﻜﻴﺪن ﺷﻴﺮه ﮔﻴﺎﻫﻲ ﻗﺎدر ﺑﻪ اﻧﺘﻘﺎل ﺑﺎﻛﺘﺮي Liberobacter asiaticum ﻋﺎﻣﻞ ﺑﻴﻤﺎري ﺧﻄﺮﻧﺎك ﮔﺮﻳﻨﻴﻨﮓ ﻣﺮﻛﺒﺎت اﺳﺖ . در اﻳﻦ ﺗﺤﻘﻴﻖ ﻓﻮن دﺷﻤﻨﺎن ﻃﺒﻴﻌﻲ ﭘﺴﻴﻞ آﺳﻴﺎﻳﻲ D. citri در اﺳﺘﺎن ﻫﺮﻣﺰﮔﺎن ﻣﻮرد ﺑﺮرﺳﻲ ﻗﺮار ﮔﺮﻓﺖ . در اﻳﻦ ﻣﻄﺎﻟﻌﻪ دو ﮔﻮﻧﻪ زﻧﺒﻮر ﭘﺎرازﻳﺘﻮﻳﻴﺪ از ﺧﺎﻧﻮاده ﻫﺎي Encyrtidae و Eulophidae ، ﻳﻚ ﮔﻮﻧﻪ ﺑﺎﻟﺘﻮري از ﺧﺎﻧﻮاده Chrysopidae ، ﭘﻨﺞ ﮔﻮﻧﻪ ﻛﻔﺸﺪوزك ﺷﻜﺎرﮔﺮ و دو ﮔﻮﻧﻪ ﻋﻨﻜﺒﻮت از ﺧﺎﻧﻮاده ﻫﺎي Salticidae و Linyphidae ﺟﻤﻊ آوري و ﺷﻨﺎﺳﺎﻳﻲ ﺷﺪﻧﺪ . در ﺑﻴﻦ د ﺷﻤﻨﺎن ﻃﺒﻴﻌﻲ ﭘﺴﻴﻞ آﺳﻴﺎﻳﻲ ﻣﺮﻛﺒﺎت، زﻧﺒﻮر ﭘﺎرازﻳﺘﻮﻳﻴﺪ Tamarixia radiata از ﺧﺎﻧﻮاده Eulophidae ﺑﺮاي اوﻟﻴﻦ ﺑﺎر از اﻳﺮان ﮔﺰارش ﻣﻲ ﺷﻮد ﻛﻪ ﻛﻪ وﻳﮋﮔﻲ ﻫﺎي ﻣﺮﻓﻮﻟﻮژﻳﻚ آن اراﻳ ﻪ ﺷﺪه اﺳﺖ. واژه ﻫﺎي ﻛﻠﻴﺪي : Diaphorna citri ، دﺷﻤﻨﺎن ﻃﺒﻴﻌﻲ، اﺳﺘﺎن ﻫﺮﻣﺰﮔﺎن ﻣﻘﺪﻣﻪ ﺷﻨﺎﺧﺖ دﺷﻤﻨﺎن ﻃﺒﻴﻌﻲ (Diaphorina citri Kuwayama (Hem., Psyllidae ﮔﺎم ﻣﻬﻢ و ﺿﺮوري ﺟﻬﺖ ﻣﺪﻳﺮﻳﺖ ﺗﻠﻔﻴﻘﻲ اﻳﻦ آﻓﺖ در ﺑﺎﻏﺎت ﻣﺮﻛﺒﺎت ﻣﻲ ﺑﺎﺷﺪ . -

Assessing Landscape Change of Minab Delta Morphs Before and After Dam Construction

Natural Environment Change, Vol. 1, No. 1, Summer & Autumn 2015, pp. 21-29 Assessing landscape change of Minab delta morphs before and after dam construction Manuchehr Farajzadeh; Professor, Department of Remote Sensing & GIS, Tarbiat Modares University, Tehran, Iran. Mohammad Kamangar; M.Sc. Remote Sensing & GIS, department of natural resources, Hormozgan University, Bandar-e-Abbas, Iran. Fahimeh Bahrami; M.Sc. Watershed Management, Department of Natural Resources, Hormozgan University, Bandar-e-Abbas, Iran. Received: April 18, 2015 - Accepted: October 5, 2015 Abstract As special depositional environments which are adjacent to the seas, deltas have provided a field for human habitat establishment. Geomorphic features of deltas are in constant transformation due to their dynamic features. Constructing dams on rivers can intensify these changes and cause either negative or positive consequences. Minab delta in Hormozgan Province of Iran is a round or crescent- shaped delta which has Esteghlal Dam constructed on its creating river. Minab Dam is constructed upstream of Minab Delta in Hormozgan Province. The research aimed to derive landscape metrics of delta and assess their changes before and after the construction of dams. Landsat Satellite images of 1983 and 2013 provided the four classes as abandoned delta, active delta, subaqueous deltaic plain and aquatic environment, using maximum likelihood method, with a Kappa Coefficient accuracy of 86.55 and 88.42 for revealing changes quantitatively. To quantify landscape metrics, percentage of landscape (PLAND), Number of Patch (NP) and Mean Patch Size (MPS) metrics were computed. As indicated by the results, the NP metric increased in all the classes except active delta, and all classes showed a reduction in MPS metric. -

Application of Thermal Remote Sensing in Earthquake Precursor Studies

APPLICATION OF THERMAL REMOTE SENSING IN EARTHQUAKE PRECURSOR STUDIES A THESIS Submitted in partial fulfilment ofthe requirements for the award of the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in EARTH SCIENCES by VINEETA RAWAT DEPARTMENT OF EARTH SCIENCES INDIAN INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY ROORKEE ROORKEE-247 667 (INDIA) SEPTEMBER, 2010 ©INDIAN INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY ROORKEE, ROORKEE, 2010 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED INDIAN INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY ROORKEE ROORKEE CANDIDATE'S DECLARATION I hereby certify that the work which is being presented in the thesis entitled APPLICATION OF THERMAL REMOTE SENSING IN EARTHQUAKE PRECURSOR STUDIES, in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy and submitted in the Department of Earth Sciences of the Indian Institute of Technology Roorkee, Roorkee is an authentic record of my own work carried out during a period from July 2006 to August 2010 under the supervision of Dr. Arun K. Saraf, Professor, Department of Earth Sciences, Dr. Josodhir Das, Scientific Officer, Department of Earthquake Engineering, Indian Institute of Technology Roorkee, Roorkee. The matter presented in this thesis has not been submitted by me for the award of any other degree of this or any other Institute. b& (VINEETA RAWAT) This is to certify that the above statement made by the candidate is correct to the best of our knowledge. (Josodhir Das ) (ArtnTK. Saraff Supervisor Supervisor Date: o-2s SeJaJ-. 2.o1 o The PhD Viva-Voce Examination of Ms. Vineeta Rawat, Research Scholar, has been held on OZ Aterr/lC// Signature of Supervisors Signature of External Examiner ABSTRACT Earthquakes are the most unexpected and devastating natural phenomenon occurring on Earth. -

Studying the Most Important Effective Factors on Dispersion of Sohaerocoma Aucheri and Its Non-Dispersion in Hormozgan

J. Basic. Appl. Sci. Res., 3(5)601-605, 2013 ISSN 2090-4304 Journal of Basic and Applied © 2013, TextRoad Publication Scientific Research www.textroad.com Studying the Most Important Effective Factors on Dispersion of Sohaerocoma Aucheri and Its Non-Dispersion in Hormozgan *S. Ghiyasi 1, A. Godari2 and R .Asad Poor3 1Department of Environment, Faculty of Agriculture, Arak Branch, Islamic Azad University, Arak, Iran 2Department of Environment, Faculty of Agriculture, Bandarabbas Branch, Islamic Azad University, Bandarabbas, Iran 3Research Center of Agricultural and Natural Sources of Hormozgan ABSTRACT Sphaerocoma aucheri is one of the important types of coastal ranges of Hormozgan Province which plays a role in the production of coastal regions and a level of 23794 hectare was allocated to its growth in this province . Studying the most effective factors in the dispersion and non-dispersion of this type to the soil study in four regions within the dispersion region of this genus and the region of lack of witness type was done via profile digging and different parameters were analyzed .The results have been shown that the average of soil factors, EC, gypsum, sand, Ca and Mg, Na, S.A.R and K amount in each three depths and factors of clay percentage and K amount in two depths and percentage of saturation moisture in 2nd depth between regions of this genus and the regions in which this type was not available, there is a significant difference (level of Duncan Test= 95%).There is a significant difference between witness regions with the regions in which this genus exits for soil acidity and sand percentage in three depths. -

Assessment of Accuracy Predict the Concentration of Nitrate Groundwater by Spatial Distribution Model (Surface Kriging Map): Hasht Bandi of Minab, Iran

IOSR Journal of Environmental Science, Toxicology and Food Technology (IOSR-JESTFT) e-ISSN: 2319-2402,p- ISSN: 2319-2399.Volume 9, Issue 4 Ver. I (Apr. 2015), PP 86-90 www.iosrjournals.org Assessment of accuracy predict the concentration of nitrate groundwater by spatial distribution model (surface kriging map): Hasht Bandi of Minab, Iran Yadolah Fakhri1, Leila Rasouli Amirhajeloo2,Athena Rafieepour3, Ghazaleh Langarizadeh4, Bigard Moradi5, Yahya Zandsalimi6, Saeedeh Jafarzadeh7,Maryam Mirzaei8,* 1Social Determinants in Health Promotion Research Center, Hormozgan University of Medical Sciences, Bandar Abbas, Iran. 2Department of Environmental Health Engineering, School of Public Health, Qom University of Medical Sciences, Qom, Iran. 3Student's research committee, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical sciences, Tehran, Iran 4Food and Drugs Research Center, Bam University of Medical Sciences, Bam, Iran 5Department of health public, Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences, Kermanshah, Iran 6Environmental Health Research Center, Kurdistan University of Medical Science, Sanandaj, Iran 7Research Center for non-communicable disease, Fasa University of Medical Sciences, Fasa, Iran 8Research Center for non-communicable disease, Msc of critical care nursing, Jahrom University of Medical Sciences, Jahrom, Iran *Corresponding author, Email: [email protected] Abstract: Recently, the spatial distribution models, such as surface kriging map were used extensively in the Assessmentof environmental pollutants such as nitrate groundwater. Therefore the Assessment of the accuracy of the maps in predicting concentration ofnitrate were determined. In this research, 162 water samples from 27 wells in HashtBandi of Minab (17 main and 10 controlled wells) were collected. The concentration of nitrate was measured by spectrophotometry DR28000 according to ferrous sulfate 8153 method. Kriging map accuracy Assessed by statistical analysis between measured and predicted concentration of nitrate in 10 controlled wells. -

The Economic Geology of Iran Mineral Deposits and Natural Resources Springer Geology

Springer Geology Mansour Ghorbani The Economic Geology of Iran Mineral Deposits and Natural Resources Springer Geology For further volumes: http://www.springer.com/series/10172 Mansour Ghorbani The Economic Geology of Iran Mineral Deposits and Natural Resources Mansour Ghorbani Faculty of Geoscience Shahid Beheshti University Tehran , Iran ISBN 978-94-007-5624-3 ISBN 978-94-007-5625-0 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-94-007-5625-0 Springer Dordrecht Heidelberg New York London Library of Congress Control Number: 2012951116 © Springer Science+Business Media Dordrecht 2013 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, speci fi cally the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on micro fi lms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. Exempted from this legal reservation are brief excerpts in connection with reviews or scholarly analysis or material supplied speci fi cally for the purpose of being entered and executed on a computer system, for exclusive use by the purchaser of the work. Duplication of this publication or parts thereof is permitted only under the provisions of the Copyright Law of the Publisher’s location, in its current version, and permission for use must always be obtained from Springer. Permissions for use may be obtained through RightsLink at the Copyright Clearance Center. Violations are liable to prosecution under the respective Copyright Law. The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. -

Prevalence and Risk Factors of Toxoplasma Gondii Infection Among Pregnant Women in Hormozgan Province, South of Iran

Iran J Parasitol: Vol. 14, No. 1, Jan-Mar 2019, pp.167-173 Iran J Parasitol Tehran University of Medical Open access Journal at Iranian Society of Parasitology Sciences Public a tion http:// ijpa.tums.ac.ir http://isp.tums.ac.ir http://tums.ac.ir Short Communication Prevalence and Risk Factors of Toxoplasma gondii Infection among Pregnant Women in Hormozgan Province, South of Iran Seyedeh Zahra KHADEMI 1,2, *Fatemeh GHAFFARIFAR 1, Abdolhosein DALIMI 1, Parivash DAVOODIAN 3, Amir ABDOLI 4,5 1. Department of Parasitology, Faculty of Medical Sciences, Tarbiat Modares University, Tehran, Iran 2. Department of Biology, Payam Noor University, Tehran, Iran 3. Infectious and Tropical Disease Research Center, Hormozgan Health Institute, Hormozgan University of Medical Sciences, Ban- dar Abbas, Iran 4. Department of Parasitology and Mycology, School of Medicine, Jahrom University of Medical Sciences, Jahrom, Iran 5. Zoonosis Research Center, Jahrom University of Medical Sciences, Jahrom, Iran Received 19 Oct 2017 Abstract Accepted 11 Jan 2018 Background: Toxoplasmosis can cause miscarriage or complications in the fetus. Diagnosis and treatment of this disease by anti-parasitic drugs especially in early pregnancy can help to prevent fetal infection and its complications. This study Keywords: aimed to determine T. gondii infection in pregnant women, evaluate risk factors in Toxoplasma gondii; the transmission of the disease and congenital toxoplasmosis. Pregnant women; Methods: Overall, 360 sera of pregnant women from 5 cities in the Hormozgan Prevalence; Province in southern Iran with different climate were evaluated from 2015-2016 Iran for T. gondii infection by using ELISA method and positive cases of IgM and IgG were tested again using Avidity IgG ELISA. -

A Reconnaissance Report on Two Iran, Makran Earthquakes

A Reconnaissance Report on two Iran, Makran Earthquakes Iran, Makran Earthquakes ; 16 April 2013, Mw7.8, Gosht (Saravan) and 11 May 2013 Irar (Goharan), Bashagard, SE of Iran Authors and Affiliations Mehdi ZARE1, Anooshiravan Ansari2, Heydar Heydari3, Mo- hammad P.M. Shahvar4, Mehdi Daneshdust5, Majid Mahdi- an6, Fereidoun Sinaiean7, Esmail Farzanegan8 and Hossein Mirzaei-Alavijeh9 1International Institute of Earthquake Engineering and Seis- mology (IIEES), Tehran, Iran, [email protected], (Member EERI) 2IIEES, [email protected] 3Relief & Rescue Organization, Iranian Red Crescent Socie- ty, Tehran, Iran 4IIEES, [email protected] 5Islamic Azad University, Science and Research Branch, Tehran, Iran ([email protected]) 6Institute of Geophysics, University of Tehran ([email protected]) 8,9Building and Housing Research Center, Tehran, Iran, (7: [email protected]), (8: [email protected]) and (9: [email protected]). report design by Brijhette Farmer, EERI Introduction Iran has experienced two strong earthquakes, in April and May 2013, in the Makran ranges within 25 days. The first earthquake occurred on 16 April 201s3, with Mw7.8 the Sa- ravan region in the eastern end of Iranian Makran. The se- cond one happened in western Makran, on 11 May 2013, with Mw6.2, in Irar, Bashagard region, close to the Minab-Zendan Fault zone. This report tries to summarize the reconnaissance reports and early seismological and earthquake engineering evaluations on these two strong earthquakes. Figure-1: The epicenter of the Gosht (Savaran), 1. Seismicity of the Makran belt. SE Iran, western Pakistan, by Norwegian Refu- gee Council (from https://www.relief-web.int). -

The Freshwater Fishes of Iran Redacted for Privacy Hs Tract Approved: Dr

AN ABSTRPCT OF THE THESIS OF Neil Brant Anuantzout for the degree of Dcctor of Philosophy in Fisheries presented on 2 Title: The Freshwater Fishes of Iran Redacted for Privacy hs tract approved: Dr. Carl E. Bond The freshwater fish fauna of Iran is representedby 3 classes, 1 orders, 31 familIes, 90 genera, 269species and 58 subspecIes. This includes 8 orders, 10 families, 14 generaand 33 species with marine representatives that live at least partof the tixne in freshwater. Also included are one family, 7 genera,9 species and 4 subspecies introduced into Iran. Overhalf the species and nearly half the genera are in the family Cypririidae; over75% of the genera and species are in the orderCypriniformes. The fish fauna may be separated into threemajor groups. The largest and nst diverse is the Sannatian Fauna,which includes the Caspian Sea, Azerbaijan, Lake Bezaiyeh, Rhorasan,Isfahan, Dashte-Kavir, and the four subbasins of the Namak LakeBasins. Of the fish found in Iran, 14 of 31 earnilies, 48 of 90 genera,127 of 269 species and 46 of 58 subspecies are found in theSarmatian Fauna. Endemisa is low, and nstly expressed at the subspecific level.The fauna contains marine relicts from the Sannatian Sea and recentinmigrants with strong relationships to the fishes of Europe, the Black Seaand northern Asia. The marine relicts are absent outside the Caspian Sea Basin, where the fauna is best described as a depauperate extensionof the Caspian and Aral Sea faunas. The second major fauna is the Nesopotamian Fauna,and includes the Tigris and Euphrates river Basins, the Karun1iver Basin, and the Kol, nd, Maliarlu, Neyriz and Lar Basins. -

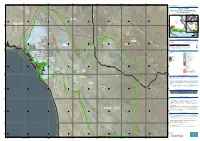

Minab Flood Delineation, V1 Minab - IRAN Flood Delineation and Flood Damage Assessment, Iran Flood Delineation, V1 - Overview Map

480000 500000 520000 540000 560000 580000 56°40'0"E 56°50'0"E 57°0'0"E 57°10'0"E 57°20'0"E 57°30'0"E 57°40'0"E 57°50'0"E GLIDE number: N/A Activation ID: EMSN066 Int. Charter call ID: N/A Product 1: AOI 01 Minab Flood delineation, v1 Minab - IRAN Flood delineation and flood damage assessment, Iran Flood delineation, v1 - Overview Map ^ Afghanistan and Rudan Helm N " N 0 ' " 0 0 ' 2 0 Iran ° Uzbekistan 2 7 Azerbaijan ° 2 7 (Islamic 2 Republic Turkmenistan Bandar-e-Abbas of) Turkey 0 0 0 0 ^Tehran s 0 0 u nd 0 0 I 01 Minab Afghanistan 2 2 PaIkrainstan 0 0 (Islamic 3 3 Iraq Republic of) Persian Gulf 02 Bandar-e-Jask Kuwait Pakistan 03 Chabahar United Saudi Arab Arabia Emirates Qatar United Arab Emirates Arabian Sea 125 India Oman km Jowzan Cartographic Information Kahnuj Full color A1, high resolution (300 dpi) Hajjiabad N 1:195000 " N 0 ' " 0 0 ' Hashtbandi 1 0 ° 1 7 ° 2 7 Dalalun Harmood 0 4 8 16 2 Kerman Minab Minan Dam km Nakhl-e Grid: WGS 1984 UTM Zone 40N map coordinate system Ebrahimi Tick marks: WGS 84 geographical coordinate system 0 0 ± 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 Legend 3 Tiab, Minab 3 Mazegh-e Bala Product 1 Reference BH140 - River Line Mazegh-e Pain Flooded Area BH020 - Canal Line BH080 - Lake Area Kulegh Kashi Boundaries BH130 - Reservoir Area Area of Interest Band-e Zarak AP030 - Primary Route Provinces AP030 - Secondary Road Municipalities AP030 - Local Road AP010 - Cart Track AQ040 - Bridge Line /" AL020 - City N " "/ N AL020 - Town 0 ' " 0 0 ' ° 0 "/ 7 ° AL020 - Village 2 7 2 "/ AL020 - Hamlet "6 AL020 - Other AL020 - Residential Built-Up Area Sarney Dam AL020 - Industrial Built-Up Area AL020 - Other Built-Up Area 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 8 8 9 9 2 Pum 2 Map Information Hormozgan Between January 9th and 13th 2020, heavy rains and river overflowing led to widespread floods, especially affecting Sistan and Baluchistan, Hormozgan and Kerman provinces in South-East Iran.