08 Chapter-III Women Visible and Women Invisible-Objects of Desire

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Letter Correspondences of Rabindranath Tagore: a Study

Annals of Library and Information Studies Vol. 59, June 2012, pp. 122-127 Letter correspondences of Rabindranath Tagore: A Study Partha Pratim Raya and B.K. Senb aLibrarian, Instt. of Education, Visva-Bharati, West Bengal, India, E-mail: [email protected] b80, Shivalik Apartments, Alakananda, New Delhi-110 019, India, E-mail:[email protected] Received 07 May 2012, revised 12 June 2012 Published letters written by Rabindranath Tagore counts to four thousand ninety eight. Besides family members and Santiniketan associates, Tagore wrote to different personalities like litterateurs, poets, artists, editors, thinkers, scientists, politicians, statesmen and government officials. These letters form a substantial part of intellectual output of ‘Tagoreana’ (all the intellectual output of Rabindranath). The present paper attempts to study the growth pattern of letters written by Rabindranath and to find out whether it follows Bradford’s Law. It is observed from the study that Rabindranath wrote letters throughout his literary career to three hundred fifteen persons covering all aspects such as literary, social, educational, philosophical as well as personal matters and it does not strictly satisfy Bradford’s bibliometric law. Keywords: Rabindranath Tagore, letter correspondences, bibliometrics, Bradfords Law Introduction a family man and also as a universal man with his Rabindranath Tagore is essentially known to the many faceted vision and activities. Tagore’s letters world as a poet. But he was a great short-story writer, written to his niece Indira Devi Chaudhurani dramatist and novelist, a powerful author of essays published in Chhinapatravali1 written during 1885- and lectures, philosopher, composer and singer, 1895 are not just letters but finer prose from where innovator in education and rural development, actor, the true picture of poet Rabindranath as well as director, painter and cultural ambassador. -

Tagore's Song Offerings: a Study on Beauty and Eternity

Everant.in/index.php/sshj Survey Report Social Science and Humanities Journal Tagore’s Song Offerings: A Study on Beauty and Eternity Dr. Tinni Dutta Lecturer, Department of Psychology , Asutosh College Kolkata , India. ABSTRACT Gitanjali written by Rabindranath Tagore (and the English translation of the Corresponding Author: Bengali poems in it, written in 1921) was awarded the Novel Prize in 1913. He Dr. Tinni Dutta called it Song Offerings. Some of the songs were taken from „Naivedya‟, „Kheya‟, „Gitimalya‟ and other selections of his poem. That is, the Supreme Being is complete only together with the soul of the devetee. He makes the mere mortal infinite and chooses to do so for His own sake, this could be just could be a faint echo of the AdvaitaPhilosophy.Tagore‟s songs in Gitanjali express the distinctive method of philosophy…The poet is nothing more than a flute (merely a reed) which plays His timeless melodies . His heart overflows with happiness at His touch that is intangible Tagore‟s song in Gitanjali are analyzed in this ways - content analysis and dynamic analysis. Methodology of his present study were corroborated with earlier findings: Halder (1918), Basu (1988), Sanyal (1992) Dutta (2002).In conclusion it could be stated that Tagore‟s songs in Gitanjali are intermingled with beauty and eternity.A frequently used theme in Tagore‟s poetry, is repeated in the song,„Tumiaamaydekechhilechhutir‟„When the day of fulfillment came I knew nothing for I was absent –minded‟, He mourns the loss. This strain of thinking is found also in an exquisite poem written in old age. -

Postcolonial Resistance of India's Cultural Nationalism in Select Films

postScriptum: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Literary Studies 25 postScriptum: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Literary Studies ISSN: 2456-7507 <postscriptum.co.in> Online – Open Access – Peer Reviewed – DOAJ Indexed Volume V Number i (January 2020) Postcolonial Resistance of India’s Cultural Nationalism in Select Films of Rituparno Ghosh Koushik Mondal Research Scholar, Department of English, Visva Bharati Koushik Mondal is presently working as a Ph. D. Scholar on the Films of Rituparno Ghosh. His area of interest includes Gender and Queer Studies, Nationalism, Postcolonialism, Postmodernism and Film Studies. He has already published some articles in prestigious national and international journals. Abstract The paper would focus on the cultural nationalism that the Indians gave birth to in response to the British colonialism and Ghosh’s critique of such a parochial nationalism. The paper seeks to expose the irony of India’s cultural nationalism which is based on the phallogocentric principle informed by the Western Enlightenment logic. It will be shown how the idea of a modern India was in fact guided by the heteronormative logic of the British masters. India’s postcolonial politics was necessarily patriarchal and hence its nationalist agenda was deeply gendered. Exposing the marginalised status of the gendered and sexual subalterns in India’s grand narrative of nationalism, Ghosh questions the compatible comradeship of the “imagined communities”. Keywords Hinduism, postcolonial, nationalism, hypermasculinity, heteronormative postscriptum.co.in Online – Open Access – Peer Reviewed – DOAJ Indexed ISSN 24567507 5.i January 20 postScriptum: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Literary Studies 26 India‟s cultural nationalism was a response to British colonialism. The celebration of masculine virility in India‟s cultural nationalism roots back to the colonial encounter. -

IP Tagore Issue

Vol 24 No. 2/2010 ISSN 0970 5074 IndiaVOL 24 NO. 2/2010 Perspectives Six zoomorphic forms in a line, exhibited in Paris, 1930 Editor Navdeep Suri Guest Editor Udaya Narayana Singh Director, Rabindra Bhavana, Visva-Bharati Assistant Editor Neelu Rohra India Perspectives is published in Arabic, Bahasa Indonesia, Bengali, English, French, German, Hindi, Italian, Pashto, Persian, Portuguese, Russian, Sinhala, Spanish, Tamil and Urdu. Views expressed in the articles are those of the contributors and not necessarily of India Perspectives. All original articles, other than reprints published in India Perspectives, may be freely reproduced with acknowledgement. Editorial contributions and letters should be addressed to the Editor, India Perspectives, 140 ‘A’ Wing, Shastri Bhawan, New Delhi-110001. Telephones: +91-11-23389471, 23388873, Fax: +91-11-23385549 E-mail: [email protected], Website: http://www.meaindia.nic.in For obtaining a copy of India Perspectives, please contact the Indian Diplomatic Mission in your country. This edition is published for the Ministry of External Affairs, New Delhi by Navdeep Suri, Joint Secretary, Public Diplomacy Division. Designed and printed by Ajanta Offset & Packagings Ltd., Delhi-110052. (1861-1941) Editorial In this Special Issue we pay tribute to one of India’s greatest sons As a philosopher, Tagore sought to balance his passion for – Rabindranath Tagore. As the world gets ready to celebrate India’s freedom struggle with his belief in universal humanism the 150th year of Tagore, India Perspectives takes the lead in and his apprehensions about the excesses of nationalism. He putting together a collection of essays that will give our readers could relinquish his knighthood to protest against the barbarism a unique insight into the myriad facets of this truly remarkable of the Jallianwala Bagh massacre in Amritsar in 1919. -

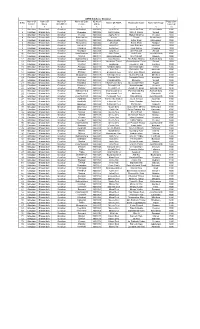

Rule Section

Rule Section CO 827/2015 Shyamal Middya vs Dhirendra Nath Middya CO 542/1988 Jayadratha Adak vs Kadan Bala Adak CO 1403/2015 Sankar Narayan das vs A.K.Banerjee CO 1945/2007 Pradip kr Roy vs Jali Devi & Ors CO 2775/2012 Haripada Patra vs Jayanta Kr Patra CO 3346/1989 + CO 3408/1992 R.B.Mondal vs Syed Ali Mondal CO 1312/2007 Niranjan Sen vs Sachidra lal Saha CO 3770/2011 lily Ghose vs Paritosh Karmakar & ors CO 4244/2006 Provat kumar singha vs Afgal sk CO 2023/2006 Piar Ali Molla vs Saralabala Nath CO 2666/2005 Purnalal seal vs M/S Monindra land Building corporation ltd CO 1971/2006 Baidyanath Garain& ors vs Hafizul Fikker Ali CO 3331/2004 Gouridevi Paswan vs Rajendra Paswan CR 3596 S/1990 Bakul Rani das &ors vs Suchitra Balal Pal CO 901/1995 Jeewanlal (1929) ltd& ors vs Bank of india CO 995/2002 Susan Mantosh vs Amanda Lazaro CO 3902/2012 SK Abdul latik vs Firojuddin Mollick & ors CR 165 S/1990 State of west Bengal vs Halema Bibi & ors CO 3282/2006 Md kashim vs Sunil kr Mondal CO 3062/2011 Ajit kumar samanta vs Ranjit kumar samanta LIST OF PENDING BENCH LAWAZIMA : (F.A. SECTION) Sl. No. Case No. Cause Title Advocate’s Name 1. FA 114/2016 Union Bank of India Mr. Ranojit Chowdhury Vs Empire Pratisthan & Trading 2. FA 380/2008 Bijon Biswas Smt. Mita Bag Vs Jayanti Biswas & Anr. 3. FA 116/2016 Sarat Tewari Ms. Nibadita Karmakar Vs Swapan Kr. Tewari 4. -

L'adieu a La Vie, 130 Alice in Wonderland, 33 Amiel's Journal, 33

Index Abbott, Lyman, 16 Bauls,46 Achebe, Chinua, 141 Bedford Chapel, Bloomsbury, 11 L'Adieu ala Vie, 130 Beerbohm, Max, 18 African writers, 143 Bengal, 12, 13, 26, 27, 28, 51, 84, 88, Ajanta Cave paintings, 8, 113 100, 110, 145 Agriculture, 96 Bengal Academy, 145 Ahmedabad, 30 Bengal partition, 17 AJfano, Franco, 123 Bengal Renaissance, 50, 51, 52, 54 AJhambra Theatre, London, 123, Bengali language, 1, 8, 13, 27, 29, 35, 127 36,42,142 Alice in Wonderland, 33 Bengali literature, 3, 8, 9, 11, 14,29, Amiel's Journal, 33 33,35,36,37,38,39,42,114 Amritsar massacre, 128 Benjamin, Walter, 109 see also Jalianwalla Bagh Beowulf, 35 massacre, Berg,AJban, 131, 132, 133 Andersen, Hans Christian, 30 Berhampore Gessore), 27 Andrews, C. F., 63, 96, 99 Berlin, 133 Anderson, James Drummond, 8 Berlin Exhibition of Tagore's art, The Arabian Nights, 30, 79, 122 108 Argentina, 97 Bhanaphul (Wild Flower), 52 Aristotle, 38 Bhanusinha (pen-name of Aronson,AJex,l04 Rabindranath Tagore), 27 Art deco, 110 Bhiirati (Bengali journal), 31, 52 Art nouveau, 110 Bharatvasher Itihasha Dhara (A Vision The Artist, 115 of India's History), 58, 59 Asian languages, 142 Bhartrhari, 124 Asian literature, 143 Bhiisa Katha, 42 Asian Review, 20 Bhattacharya, Upendranath, 43 The Athenaeum (journal), 6, 17 Bidou, Henri, 106, 107 Attenborough, Richard, 153 Birdwood, Sir George, 7, 8 Aurobindo Ghose, 50 Birmingham Exhibition of Tagore's Art, 106 Bach, J. S., 106 Bisarjan (Sacrifice), 143 Baines, William, 127 see also Sacrifice Balak (Bengali journal), 31, 32 Blake, William, 6 Balej, -

Government of Assam OFFICE of the COMMISSIONER of TAXES

Government of Assam OFFICE OF THE COMMISSIONER OF TAXES PROVISIONAL LIST OF CANDIDATES FOR THE POSTS OF JUNIOR ASSISTANT UNDER THE COMMISSIONER OF TAXES, GOVERNMENT OF ASSAM Sl No Online Application No. Name of the CandidateFather Name Mother Name 1 199005617 A R AMIN ULLA RAHIMUDDIN AHMED KARIMAN NESSA 2 199005659 A R ATIQUE ULLA RAHIMUDDIN AHMED KARIMAN NESSA 3 199003745 AARTI KUMARI RAM CHANDAR PRASAD SADHNA DEVI 4 199008979 ABANI DOLEY KASHINATH DOLEY ANJULI DOLEY 5 199010295 ABANI KANTA SINGHA RADHA KANTA SINGHA ABHOYA RANI SINHA 6 199008302 ABANI PHUKAN DILESWAR PHUKAN LICI PHANGCHOPI 7 199003746 ABDUL AHAD CHOUDHURY ATAUR RAHMAN CHOUDHURY RABIA KHANAM CHOUDHURY 8 199011920 ABDUL BATEN KASEM ALI SHUKITAN NESSA 9 199006876 ABDUL HAMIM LASKAR ABDUL MANAF LASKAR HALIMA KHATUN LASKAR 10 199002148 ABDUL HASIM MD NAZMUL HAQUE DELANGISH BEGUM 11 199009460 ABDUL HUSSAIN BULMAJAN ALI AJEBUN NESSA BEGUM 12 199001151 ABDUL KADIR ALI ANOWAR HUSSAIN AIAJUN BEGUM 13 199003077 ABDUL KHAN NUR HUSSAIN KHAN MONICA KHATOON 14 199002194 ABDUL MAHSIN HOQUE MD NAZMUL HOQUE DELANGISH BEGUM 15 199009870 ABDUL MALIK MUZAMMEL HOQUE AZEDA BEGUM 16 199010603 ABDUL MANNAN JULHAS ALI FIROZA BEGUM 17 199012475 ABDUL MAZID FAZAR ALI RUPJAN BEGUM 18 199005498 ABDUL MOTLIB ABDUL AZIM ILA BEGUM 19 199000721 ABDUL MUNIM AHMED ABDUS SAMAD AHMED NASIM BANU AKAND 20 199010439 ABDUL ROSHID SURHAB ALI MAHARUMA BEGUM 21 199003052 ABDUL SAYED ABDUL LATIF MEAH SAIRA KHATUN 22 199003735 ABDUL WADUD HAKIM ALI MANOWARA BEGUM 23 199000601 ABDUL WASHIF AHMED HASIB AHMED ANUARA -

Visva-Bharati, Santiniketan Title Accno Language Author / Script Folios DVD Remarks

www.ignca.gov.in Visva-Bharati, Santiniketan Title AccNo Language Author / Script Folios DVD Remarks CF, All letters to A 1 Bengali Many Others 75 RBVB_042 Rabindranath Tagore Vol-A, Corrected, English tr. A Flight of Wild Geese 66 English Typed 112 RBVB_006 By K.C. Sen A Flight of Wild Geese 338 English Typed 107 RBVB_024 Vol-A A poems by Dwijendranath to Satyendranath and Dwijendranath Jyotirindranath while 431(B) Bengali Tagore and 118 RBVB_033 Vol-A, presenting a copy of Printed Swapnaprayana to them A poems in English ('This 397(xiv Rabindranath English 1 RBVB_029 Vol-A, great utterance...') ) Tagore A song from Tapati and Rabindranath 397(ix) Bengali 1.5 RBVB_029 Vol-A, stage directions Tagore A. Perumal Collection 214 English A. Perumal ? 102 RBVB_101 CF, All letters to AA 83 Bengali Many others 14 RBVB_043 Rabindranath Tagore Aakas Pradeep 466 Bengali Rabindranath 61 RBVB_036 Vol-A, Tagore and 1 www.ignca.gov.in Visva-Bharati, Santiniketan Title AccNo Language Author / Script Folios DVD Remarks Sudhir Chandra Kar Aakas Pradeep, Chitra- Bichitra, Nabajatak, Sudhir Vol-A, corrected by 263 Bengali 40 RBVB_018 Parisesh, Prahasinee, Chandra Kar Rabindranath Tagore Sanai, and others Indira Devi Bengali & Choudhurani, Aamar Katha 409 73 RBVB_029 Vol-A, English Unknown, & printed Indira Devi Aanarkali 401(A) Bengali Choudhurani 37 RBVB_029 Vol-A, & Unknown Indira Devi Aanarkali 401(B) Bengali Choudhurani 72 RBVB_029 Vol-A, & Unknown Aarogya, Geetabitan, 262 Bengali Sudhir 72 RBVB_018 Vol-A, corrected by Chhelebele-fef. Rabindra- Chandra -

Setting the Stage: a Materialist Semiotic Analysis Of

SETTING THE STAGE: A MATERIALIST SEMIOTIC ANALYSIS OF CONTEMPORARY BENGALI GROUP THEATRE FROM KOLKATA, INDIA by ARNAB BANERJI (Under the Direction of Farley Richmond) ABSTRACT This dissertation studies select performance examples from various group theatre companies in Kolkata, India during a fieldwork conducted in Kolkata between August 2012 and July 2013 using the materialist semiotic performance analysis. Research into Bengali group theatre has overlooked the effect of the conditions of production and reception on meaning making in theatre. Extant research focuses on the history of the group theatre, individuals, groups, and the socially conscious and political nature of this theatre. The unique nature of this theatre culture (or any other theatre culture) can only be understood fully if the conditions within which such theatre is produced and received studied along with the performance event itself. This dissertation is an attempt to fill this lacuna in Bengali group theatre scholarship. Materialist semiotic performance analysis serves as the theoretical framework for this study. The materialist semiotic performance analysis is a theoretical tool that examines the theatre event by locating it within definite material conditions of production and reception like organization, funding, training, availability of spaces and the public discourse on theatre. The data presented in this dissertation was gathered in Kolkata using: auto-ethnography, participant observation, sample survey, and archival research. The conditions of production and reception are each examined and presented in isolation followed by case studies. The case studies bring the elements studied in the preceding section together to demonstrate how they function together in a performance event. The studies represent the vast array of theatre in Kolkata and allow the findings from the second part of the dissertation to be tested across a variety of conditions of production and reception. -

JA-097-17-III (Rabindra Sangit) Inst.P65

www.a2zSubjects.com PAPER-III RABINDRA SANGIT Signature and Name of Invigilator 1. (Signature) __________________________ OMR Sheet No. : ............................................... (Name) ____________________________ (To be filled by the Candidate) 2. (Signature) __________________________ Roll No. (Name) ____________________________ (In figures as per admission card) Roll No.________________________________ J A 0 9 7 1 7 (In words) 1 Time : 2 /2 hours] [Maximum Marks : 150 Number of Pages in this Booklet : 32 Number of Questions in this Booklet : 75 Instructions for the Candidates ¯Ö¸üßõÖÖÙ£ÖµÖÖë Ûêú ×»Ö‹ ×®Ö¤ìü¿Ö 1. Write your roll number in the space provided on the top of 1. ‡ÃÖ ¯Öéšü Ûêú ‰ú¯Ö¸ü ×®ÖµÖŸÖ Ã£ÖÖ®Ö ¯Ö¸ü †¯Ö®ÖÖ ¸üÖê»Ö ®Ö´²Ö¸ü ×»Ö×ÜÖ‹ … this page. 2. ‡ÃÖ ¯ÖÏ¿®Ö-¯Ö¡Ö ´Öë ¯Ö“ÖÆü¢Ö¸ü ²ÖÆãü×¾ÖÛú»¯ÖßµÖ ¯ÖÏ¿®Ö Æïü … 2. This paper consists of seventy five multiple-choice type of 3. ¯Ö¸üßõÖÖ ¯ÖÏÖ¸ü´³Ö ÆüÖê®Öê ¯Ö¸ü, ¯ÖÏ¿®Ö-¯Öã×ßÖÛúÖ †Ö¯ÖÛúÖê ¤êü ¤üß •ÖÖµÖêÝÖß … ¯ÖÆü»Öê questions. ¯ÖÖÑ“Ö ×´Ö®Ö™ü †Ö¯ÖÛúÖê ¯ÖÏ¿®Ö-¯Öã×ßÖÛúÖ ÜÖÖê»Ö®Öê ŸÖ£ÖÖ ˆÃÖÛúß ×®Ö´®Ö×»Ö×ÜÖŸÖ 3. At the commencement of examination, the question booklet •ÖÖÑ“Ö Ûêú ×»Ö‹ פüµÖê •ÖÖµÖëÝÖê, וÖÃÖÛúß •ÖÖÑ“Ö †Ö¯ÖÛúÖê †¾Ö¿µÖ Ûú¸ü®Öß Æîü : will be given to you. In the first 5 minutes, you are requested (i) to open the booklet and compulsorily examine it as below : ¯ÖÏ¿®Ö-¯Öã×ßÖÛúÖ ÜÖÖê»Ö®Öê Ûêú ×»Ö‹ ¯Öã×ßÖÛúÖ ¯Ö¸ü »ÖÝÖß ÛúÖÝÖ•Ö Ûúß ÃÖᯙ (i) To have access to the Question Booklet, tear off the paper ÛúÖê ±úÖ›Ìü »Öë … ÜÖã»Öß Æãü‡Ô µÖÖ ×²Ö®ÖÖ Ã™üßÛú¸ü-ÃÖᯙ Ûúß ¯Öã×ßÖÛúÖ seal on the edge of this cover page. -

Compiled Ghazipur

ASHA Database Ghazipur Name Of Name Of Name Of Name Of Sub- ID No.of Population S.No. Name Of ASHA Husband's Name Name Of Village District Block CHC/BPHC Centre ASHA Covered 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 1 Ghazipur Bhawarkole Gondour Mirjabad 3003001 Aarti Devi Awadesh Ram Devchandpur 1000 2 Ghazipur Bhawarkole Gondour Chandpur 3003002 Aarti Thakur Shiv Ji Thakur Sonadi 1000 3 Ghazipur Bhawarkole Gondour Veerpur 3003003 Aasha Devi Madan Sharma Veerpur 1000 4 Ghazipur Bhawarkole Gondour Pakhanpura 3003004 Aasiya Taukir Pakhanpura 1000 5 Ghazipur Bhawarkole Gondour Bhawarkole 3003005 Afsana Khatun Akbar Khan Maheshpur 1000 6 Ghazipur Bhawarkole Gondour Bhawarkole 3003006 Ahamadi Kalim Khan Ranipur 1000 7 Ghazipur Bhawarkole Gondour Awathahi 3003007 Anita Devi Jang Bahadur Awathahi 1000 8 Ghazipur Bhawarkole Gondour Khardiya 3003008 Anita Devi Indal Dubey Khardiya 1000 9 Ghazipur Bhawarkole Gondour Chandpur 3003009 Anju Devi Om Prakash Sonadi 1000 10 Ghazipur Bhawarkole Gondour Joga Musahib 3003010 Anju Gupta AnilKharwar Gupta Joga Musahib 1000 11 Ghazipur Bhawarkole Gondour Maniya 3003011 Anju Kushwaha Om Prakash Maniya 1000 12 Ghazipur Bhawarkole Gondour Sukhadehara 3003012 Anju Shukla Brij kushwahaBihari Shukla Sukhadehara 1000 13 Ghazipur Bhawarkole Gondour Chandpur 3003013 Anupama Tiwari Ramashankar Tiwari Sonadi 1000 14 Ghazipur Bhawarkole Gondour Gondour 3003014 Arpita Rai Umesh Kr. Rai Gondour 1000 15 Ghazipur Bhawarkole Gondour Amrupur 3003015 Bandana Ojha Harivansh Ojha Vatha 1000 16 Ghazipur Bhawarkole Gondour Awathahi 3003016 Bebi Rai -

February 18, 2014 (Series 28: 4) Satyajit Ray, CHARULATA (1964, 117 Minutes)

February 18, 2014 (Series 28: 4) Satyajit Ray, CHARULATA (1964, 117 minutes) Directed by Satyajit Ray Written byRabindranath Tagore ... (from the story "Nastaneer") Cinematography by Subrata Mitra Soumitra Chatterjee ... Amal Madhabi Mukherjee ... Charulata Shailen Mukherjee ... Bhupati Dutta SATYAJIT RAY (director) (b. May 2, 1921 in Calcutta, West Bengal, British India [now India]—d. April 23, 1992 (age 70) in Calcutta, West Bengal, India) directed 37 films and TV shows, including 1991 The Stranger, 1990 Branches of the Tree, 1989 An Enemy of the People, 1987 Sukumar Ray (Short documentary), 1984 The Home and the World, 1984 (novel), 1979 Naukadubi (story), 1974 Jadu Bansha (lyrics), “Deliverance” (TV Movie), 1981 “Pikoor Diary” (TV Short), 1974 Bisarjan (story - as Kaviguru Rabindranath), 1969 Atithi 1980 The Kingdom of Diamonds, 1979 Joi Baba Felunath: The (story), 1964 Charulata (from the story "Nastaneer"), 1961 Elephant God, 1977 The Chess Players, 1976 Bala, 1976 The Kabuliwala (story), 1961 Teen Kanya (stories), 1960 Khoka Middleman, 1974 The Golden Fortress, 1973 Distant Thunder, Babur Pratyabartan (story - as Kabiguru Rabindranath), 1960 1972 The Inner Eye, 1972 Company Limited, 1971 Sikkim Kshudhita Pashan (story), 1957 Kabuliwala (story), 1956 (Documentary), 1970 The Adversary, 1970 Days and Nights in Charana Daasi (novel "Nauka Doobi" - uncredited), 1947 the Forest, 1969 The Adventures of Goopy and Bagha, 1967 The Naukadubi (story), 1938 Gora (story), 1938 Chokher Bali Zoo, 1966 Nayak: The Hero, 1965 “Two” (TV Short), 1965 The (novel), 1932 Naukadubi (novel), 1932 Chirakumar Sabha, 1929 Holy Man, 1965 The Coward, 1964 Charulata, 1963 The Big Giribala (writer), 1927 Balidan (play), and 1923 Maanbhanjan City, 1962 The Expedition, 1962 Kanchenjungha, 1961 (story).