Frontiers of Faith

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Cistercian Abbey of Coupar Angus, C.1164-C.1560

1 The Cistercian Abbey of Coupar Angus, c.1164-c.1560 Victoria Anne Hodgson University of Stirling Submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy August 2016 2 3 Abstract This thesis is an examination of the Cistercian abbey of Coupar Angus, c.1164-c.1560, and its place within Scottish society. The subject of medieval monasticism in Scotland has received limited scholarly attention and Coupar itself has been almost completely overlooked, despite the fact that the abbey possesses one of the best sets of surviving sources of any Scottish religious house. Moreover, in recent years, long-held assumptions about the Cistercian Order have been challenged and the validity of Order-wide generalisations disputed. Historians have therefore highlighted the importance of dedicated studies of individual houses and the need to incorporate the experience of abbeys on the European ‘periphery’ into the overall narrative. This thesis considers the history of Coupar in terms of three broadly thematic areas. The first chapter focuses on the nature of the abbey’s landholding and prosecution of resources, as well as the monks’ burghal presence and involvement in trade. The second investigates the ways in which the house interacted with wider society outside of its role as landowner, particularly within the context of lay piety, patronage and its intercessory function. The final chapter is concerned with a more strictly ecclesiastical setting and is divided into two parts. The first considers the abbey within the configuration of the Scottish secular church with regards to parishes, churches and chapels. The second investigates the strength of Cistercian networks, both domestic and international. -

Levens Hall & Gardens

LAKE DISTRICT & CUMBRIA GREAT HERITAGE 15 MINUTES OF FAME www.cumbriaslivingheritage.co.uk Abbot Hall Art Gallery, Kendal Cumbria Living Heritage Members’ www.abbothall.org.uk ‘15 Minutes of Fame’ Claims Cumbria’s Living Heritage members all have decades or centuries of history in their Abbot Hall is renowned for its remarkable collection locker, but in the spirit of Andy Warhol, in what would have been the month of his of works, shown off to perfection in a Georgian house 90th birthday, they’ve crystallised a few things that could be further explored in 15 dating from 1759, which is one of Kendal’s finest minutes of internet research. buildings. It has a significant collection of works by artists such as JMW Turner, J R Cozens, David Cox, Some have also breathed life into the famous names associated with them, to Edward Lear and Kurt Schwitters, as well as having a reimagine them in a pop art style. significant collection of portraits by George Romney, who served his apprenticeship in Kendal. This includes All of their claims to fame would occupy you for much longer than 15 minutes, if a magnificent portrait - ‘The Gower Children’. The you visited them to explore them further, so why not do that and discover how other major piece in the gallery is The Great Picture, a interesting heritage can be? Here’s a top-to-bottom-of-the-county look at why they triptych by Jan van Belcamp portraying the 40-year all have something to shout about. struggle of Lady Anne Clifford to gain her rightful inheritance, through illustrations of her circumstances at different times during her life. -

The Seaside Resorts of Westmorland and Lancashire North of the Sands in the Nineteenth Century

THE SEASIDE RESORTS OF WESTMORLAND AND LANCASHIRE NORTH OF THE SANDS IN THE NINETEENTH CENTURY BY ALAN HARRIS, M.A., PH.D. READ 19 APRIL 1962 HIS paper is concerned with the development of a group of Tseaside resorts situated along the northern and north-eastern sides of Morecambe Bay. Grange-over-Sands, with a population in 1961 of 3,117, is the largest member of the group. The others are villages, whose relatively small resident population is augmented by visitors during the summer months. Although several of these villages have grown considerably in recent years, none has yet attained a population of more than approxi mately 1,600. Walney Island is, of course, exceptional. Since the suburbs of Barrow invaded the island, its population has risen to almost 10,000. Though small, the resorts have an interesting history. All were affected, though not to the same extent, by the construction of railways after 1846, and in all of them the legacy of the nineteenth century is still very much in evidence. There are, however, some visible remains and much documentary evidence of an older phase of resort development, which preceded by several decades the construction of the local railways. This earlier phase was important in a number of ways. It initiated changes in what were then small communities of farmers, wood-workers and fishermen, and by the early years of the nineteenth century old cottages and farmsteads were already being modified to cater for the needs of summer visitors. During the early phase of development a handful of old villages and hamlets became known to a select few. -

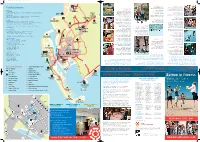

Barrow Map Leaflet 28728 11/1/07 12:06 Page 1

Barrow Map Leaflet_28728 11/1/07 12:06 Page 1 Tel: 01229 474251. 01229 Tel: Tel: 01229 430600. 01229 Tel: WC u School. Riding Seaview specially trained owls/bird of prey. of owls/bird trained specially by the sea with sea the by horse a Ride Travelling to Barrow 835449. 01229 Tel: ASKAM from displays regular as well as diverse night life. life. night diverse - see a variety of owls of variety a see - owls Furness - IN - trails. waymarked BY CAR q and lively having for reputation countryside and seaside and countryside which adds further to the town’s the to further adds which From The M6 FURNESS 824334. 01229 Tel: the network of network the A595 Walk on board the Princess Selandia, Princess the board on Leave the Motorway at junction 36, then follow the A590 all the way to Barrow. restaurant. family and ROANHEAD LINDAL state of the art floating nightspot floating art the of state - indoor play area play indoor - BEACH Warehouse Wacky - IN - courses. excellent 3 Barrow’s is Barrow’s latest Barrow’s is From The Lakes Lagoon Blue The enthusiasts can play on play can enthusiasts Golf Take the A592 from Bowness along the Eastern shore of Lake Windermere. FURNESS A590 823823. 01229 Tel: Tel: 01229 823823 01229 Tel: Lazerzone. of Join the A590 which takes you straight to Barrow. t SOUTH LAKES WILD eatery. stylish and WC 470303. 01229 Tel: bar, childrens play area and venue and area play childrens bar, - indoor play area area play indoor - ANIMAL PARK Playzone West Kitesurfing. West - stylish eatery, stylish - BY TRAIN House Custom The railway and play areas. -

William Le Fleming, Richard Le Fleming &C

CUMBERLAND & WESTMORLAND ANTIQUARIAN & ARCHJEOLOGICAL SOCIETY. TRACT SERIES, No. XI. THE MEMOIRS OF SIR DANIEL FLEMING TRANSCRIBED BY R. E. PORTER AND EDITED BY W. G. COLLINGWOOD. KENDAL TITUS WILSON & SON 1928. KENDAL: PRINTED BY TITUS WILSON & SON, 28, Highgate. 1928. CONTENTS. PAGE... Editor's Preface Vll Sir Daniel Fleming, from the portrait at Rydal Hall . to /ace I The Earls of Flanders and the Flemings .. I Michael le Fleming of Furness .. 5 William f. Michael le Fleming and his family II Richard f. Michael le Fleming and the family of Beckermet . Richard f. John le Fleming and the family at Coniston and Beckermet . Thomas f. Thomas Fleming and the family at • Rydal and Coniston . 37 The Flemings of Conistori, Rydal and Skirwith · ... 56 William f. John Fleming, 1628-1649 .. 64 Daniel Fleming of Skirwith and his family 66 Sir Daniel Fleming, his autobiography 73 Description of Caernarvon Castle 81 Gleaston Castle .. 82 Coniston . 82 Rydal . 85 The arms belonging to the family of Fleming ~9 Sir Daniel Fleming's advice to his son 92 Appendix I ; Beckermet documents 98 Appendix II; Rydal documents .. I03 Appendix III ; Kirkland documents . Il2 Index . II8 EDITOR'S PREFACE. Our Society has already printed, in the Tract Series of which this volume is the latest, two short works by Sir Daniel Fleming of Rydal, his Surveys of Cumberland and of Westmorland. These Memoirs were long lost, and his own manuscript, if there was such in any complete form, is still unknown; but an early copy was found and transcribed by Mr. R. E. Porter, and with the leave of Stanley Hughes le Fleming Esq., of Rydal Hall, is now printed. -

Furness Abbey, Barrow-In- Furness, Cumbria

FURNESS ABBEY, BARROW-IN- FURNESS, CUMBRIA Archaeological Evaluation Oxford Archaeology North February 2011 English Heritage Issue No: 2010-11/1155 OA North Job No: L9833 NGR: SD 218 717 SMC Ref: S00001899 Furness Abbey, Barrow-in-Furness, Cumbria: Archaeological Evaluation 1 CONTENTS SUMMARY ..................................................................................................................3 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ..............................................................................................4 1. INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................................5 1.1 Circumstances of the Project .............................................................................5 1.2 Site Location, Topography and Geology............................................................5 1.3 Archaeological and Historical Background........................................................5 2. METHODOLOGY .....................................................................................................7 2.1 Project Design...................................................................................................7 2.2 Evaluation Trenching ........................................................................................7 2.3 Artefacts............................................................................................................7 2.4 Archive .............................................................................................................7 3. -

RIEVAULX ABBEY and ITS SOCIAL ENVIRONMENT, 1132-1300 Emilia

RIEVAULX ABBEY AND ITS SOCIAL ENVIRONMENT, 1132-1300 Emilia Maria JAMROZIAK Submitted in Accordance with the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Leeds School of History September 2001 The candidate confirms that the work submitted is her own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others i ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I would like to express my gratitude to my supervisor Dr Wendy Childs for her continuous help and encouragement at all stages of my research. I would also like to thank other faculty members in the School of History, in particular Professor David Palliser and Dr Graham Loud for their advice. My thanks go also to Dr Mary Swan and students of the Centre for Medieval Studies who welcomed me to the thriving community of medievalists. I would like to thank the librarians and archivists in the Brotherton Library Leeds, Bodleian Library Oxford, British Library in London and Public Record Office in Kew for their assistance. Many people outside the University of Leeds discussed several aspects of Rievaulx abbey's history with me and I would like to thank particularly Dr Janet Burton, Dr David Crouch, Professor Marsha Dutton, Professor Peter Fergusson, Dr Brian Golding, Professor Nancy Partner, Dr Benjamin Thompson and Dr David Postles as well as numerous participants of the conferences at Leeds, Canterbury, Glasgow, Nottingham and Kalamazoo, who offered their ideas and suggestions. I would like to thank my friends, Gina Hill who kindly helped me with questions about English language, Philip Shaw who helped me to draw the maps and Jacek Wallusch who helped me to create the graphs and tables. -

Historic England Listings for Barrow in Furness

Historic England Listings For Barrow In Furness The Full Details (And In Most Cases For Listed Buildings, A Photograph) Are Given In The Historic England Website And Each Is Linked From The Item Title. Included There Are Maps On Which The Property Is Located By A (Very) Small Blue Triangle. Listed Buildings Duke Street 4, Duke Street, 63, 65 And 67, Duke Street 77 And 79, Duke Street, 81-89, Duke Street Barclays Bank Bank Chambers The Old Bank 111-119, Duke Street, The Lord Ramsden Public House 125, Duke Street, 127, 129 And 131, Duke Street, Barrow In Furness Alfred Barrow School, Centre Block Burlington House Church Of St Mary Of Furness Presbytery To Church Of St Mary Of Furness With Wall Connecting To Church Church Of St James Hotel Majestic Hotel Imperial National Westminster Bank Public Library, Museum And Forecourt Wall And Railings Facing Ramsden Square Pair Of K6 Telephone Kiosks Adjacent To Public Library Statue Of Henry Schneider Statue Of Sir James Ramsden Statue Of Lord Frederick Cavendish At Junction With North Road The Albion Public House Town Hall Abbey Road Central Fire Station College Of Further Education Annexe Including Front Railings And Piers Conservative Club Cooke's Buildings Oxford Chambers Duke Of Edinburgh Hotel 298, Abbey Road, Barrow In Furness Jubilee Bridge Oaklands Ramsden Hall Working Men's Club And Institute Furness Abbey Area Furness Abbey, Including All Medieval Remains In Care Of English Heritage Grade I Abbey Gate Cottages Abbey House Hotel, Grade: II* West Lodge To Abbey House With Attached Gatehouse -

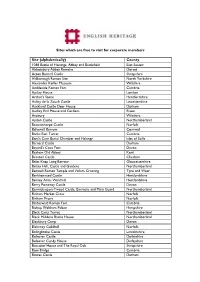

Site (Alphabetically)

Sites which are free to visit for corporate members Site (alphabetically) County 1066 Battle of Hastings, Abbey and Battlefield East Sussex Abbotsbury Abbey Remains Dorset Acton Burnell Castle Shropshire Aldborough Roman Site North Yorkshire Alexander Keiller Museum Wiltshire Ambleside Roman Fort Cumbria Apsley House London Arthur's Stone Herefordshire Ashby de la Zouch Castle Leicestershire Auckland Castle Deer House Durham Audley End House and Gardens Essex Avebury Wiltshire Aydon Castle Northumberland Baconsthorpe Castle Norfolk Ballowall Barrow Cornwall Banks East Turret Cumbria Bant's Carn Burial Chamber and Halangy Isles of Scilly Barnard Castle Durham Bayard's Cove Fort Devon Bayham Old Abbey Kent Beeston Castle Cheshire Belas Knap Long Barrow Gloucestershire Belsay Hall, Castle and Gardens Northumberland Benwell Roman Temple and Vallum Crossing Tyne and Wear Berkhamsted Castle Hertfordshire Berney Arms Windmill Hertfordshire Berry Pomeroy Castle Devon Berwick-upon-Tweed Castle, Barracks and Main Guard Northumberland Binham Market Cross Norfolk Binham Priory Norfolk Birdoswald Roman Fort Cumbria Bishop Waltham Palace Hampshire Black Carts Turret Northumberland Black Middens Bastle House Northumberland Blackbury Camp Devon Blakeney Guildhall Norfolk Bolingbroke Castle Lincolnshire Bolsover Castle Derbyshire Bolsover Cundy House Derbyshire Boscobel House and The Royal Oak Shropshire Bow Bridge Cumbria Bowes Castle Durham Boxgrove Priory West Sussex Bradford-on-Avon Tithe Barn Wiltshire Bramber Castle West Sussex Bratton Camp and -

Urswick Parish Plan 2006

'" U-rswick PC1-rish Ncrl::ul"e's hand blessed this pal"ish with a beautLl and chamctel" which few can l"ival. Good fortune then favoul"ed us with fOl"ebeal"s whose cal"ing hand - and fol" ~ a few, with the ultimate saC1"ifice- .J ~I I passed on to us the splendoul" .. f I that we now shal"e. Let us not be found wanting in OUl"l"espect fol" what those who I went befol"e have left: behind, 01"in OUl"dutLl to those who will succeed us. MaLI theLl in theil" tU1"nl"evel"e it as a home, which compels theil" affection, and is worthLl of theil" ca1"e. .J1£//\Y)! f,~ ~ (/h"fii ) :J'Y"') ~ .I.{f G...J_~J/f URSWICK PARISH PLAN EDITION 1 2006 Contents I Introduction I 2 Spiritual Expression and Development 4 3 Listed Buildings in the Parish 5 4 Educating the Junior Citizens of the Parish 6 5 Employment in the Parish 6 6 Services IIIthe Parish 8 7 Parish Amenities 9 8 Community Groups and Associations 10 9 Surveys of Parish Residents' Concerns and Aspirations 12 10 ConcernsandActionPlans- Parishwideitems 14 11 ConcernsandActionPlans- Bardsea items 19 12 Concerns and Action Plans - Urswick villages items 22 13 ConcernsandActionPlans- StaintonwithAdgarleyitems 25 14 Acknowledgements 27 OISWICI PARISHPLAN 1 Introduction Located to the east of the A590 trunk road on the Furness Peninsula in Cumbria, the border of Urswick Parish is 1.7 miles south of Ulverston town centre and 3.4 miles north of Barrow in Furness town centre. -

Gleaston Castle, Gleaston, Cumbria Results of Aerial Survey And

Gleaston Castle, Gleaston, Cumbria Results of Aerial Survey and Conservation Statement Helen Evans and Daniel Elsworth April 2016 Gleaston Castle: Aerial Survey and Conservation Statement 1 Summary Gleaston Castle is located on the Furness Peninsula, South Cumbria and is a fortified manor in the form of a courtyard or enclosure castle. The site, now ruinous, originally consisted of a large hall and three towers joined by a substantial curtain wall. The castle may have been constructed in the early 14th Century when Cumbria was subject to raids from Scotland under Robert the Bruce, although there is not necessarily any direct connection to these events, especially given that it is not mentioned in documentary sources before 1350. After a relatively short period as a manorial residence the site was abandoned in the mid-15th Century and recorded as a ruin in the mid-16th Century. Despite the attentions of antiquarians, the history and remains of Gleaston Castle are poorly understood. It has never been fully recorded and required a detailed archaeological survey to better understand its significance and inform future conservation strategies. Elements of the ruinous remains of the castle are in a dangerous structural condition requiring extensive repair and consolidation to make them safe. For this reason the site, immediately adjacent to a public road, is not publically accessible. Gleaston Castle is a Scheduled Ancient Monument and a Grade 1 listed building. Presently there is no coherent management structure in place or funds available for its conservation. Although the castle has significant historical, archaeological and tourism potential, the present complexities of its situation have led to a lack of intervention. -

The Political Culture of the English Commons, C.1550–1650* the Political Culture of the English Commons by Jonathan Healey

The political culture of the English commons, c.1550–1650* the political culture of the english commons by Jonathan Healey Abstract Although there has been plenty of work on enclosure and the riots against it, the ‘political culture’ of common lands remains obscure, despite considerable interest amongst social historians in ‘everyday politics’ and ‘weapons of the weak’. This article attempts to recover something of that culture, asking what political meaning was ascribed to certain actions, events and landscape features, and what tactics commoners used to further their micro-political ends. Using a systematic study of interrogatories and depositions in the Court of Exchequer, it finds a complex array of political weaponry deployed in commoning disputes, from gossip, threats and animal-maiming to interpersonal violence. In addition, it shows that the need to establish precedent, or ‘long-usage’, meant that certain physical acts and features were imbued with political meaning: acts of use, perambulations, old ridge-and-furrow, speech, even dying whispers, could all mean something in the politics of the commons. Moreover, commoners could be subject to moral scrutiny as neighbours, with antisocial behaviour liable to be used against them in disputes. All in all, it is argued that we are only just beginning to recover the politics of the English commons, and that there was much more to them than enclosure rioting. Commons are political spaces. They are shared between people, and their survival depends on regulation and co-operation.1 More than this, they are often physically ill-defined, as are rights to use them. Whereas, broadly speaking, a person’s rights on a private plot are clearly defined, those on a common are often not.