Ossick Coots and Collared Doves

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Cistercian Abbey of Coupar Angus, C.1164-C.1560

1 The Cistercian Abbey of Coupar Angus, c.1164-c.1560 Victoria Anne Hodgson University of Stirling Submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy August 2016 2 3 Abstract This thesis is an examination of the Cistercian abbey of Coupar Angus, c.1164-c.1560, and its place within Scottish society. The subject of medieval monasticism in Scotland has received limited scholarly attention and Coupar itself has been almost completely overlooked, despite the fact that the abbey possesses one of the best sets of surviving sources of any Scottish religious house. Moreover, in recent years, long-held assumptions about the Cistercian Order have been challenged and the validity of Order-wide generalisations disputed. Historians have therefore highlighted the importance of dedicated studies of individual houses and the need to incorporate the experience of abbeys on the European ‘periphery’ into the overall narrative. This thesis considers the history of Coupar in terms of three broadly thematic areas. The first chapter focuses on the nature of the abbey’s landholding and prosecution of resources, as well as the monks’ burghal presence and involvement in trade. The second investigates the ways in which the house interacted with wider society outside of its role as landowner, particularly within the context of lay piety, patronage and its intercessory function. The final chapter is concerned with a more strictly ecclesiastical setting and is divided into two parts. The first considers the abbey within the configuration of the Scottish secular church with regards to parishes, churches and chapels. The second investigates the strength of Cistercian networks, both domestic and international. -

Levens Hall & Gardens

LAKE DISTRICT & CUMBRIA GREAT HERITAGE 15 MINUTES OF FAME www.cumbriaslivingheritage.co.uk Abbot Hall Art Gallery, Kendal Cumbria Living Heritage Members’ www.abbothall.org.uk ‘15 Minutes of Fame’ Claims Cumbria’s Living Heritage members all have decades or centuries of history in their Abbot Hall is renowned for its remarkable collection locker, but in the spirit of Andy Warhol, in what would have been the month of his of works, shown off to perfection in a Georgian house 90th birthday, they’ve crystallised a few things that could be further explored in 15 dating from 1759, which is one of Kendal’s finest minutes of internet research. buildings. It has a significant collection of works by artists such as JMW Turner, J R Cozens, David Cox, Some have also breathed life into the famous names associated with them, to Edward Lear and Kurt Schwitters, as well as having a reimagine them in a pop art style. significant collection of portraits by George Romney, who served his apprenticeship in Kendal. This includes All of their claims to fame would occupy you for much longer than 15 minutes, if a magnificent portrait - ‘The Gower Children’. The you visited them to explore them further, so why not do that and discover how other major piece in the gallery is The Great Picture, a interesting heritage can be? Here’s a top-to-bottom-of-the-county look at why they triptych by Jan van Belcamp portraying the 40-year all have something to shout about. struggle of Lady Anne Clifford to gain her rightful inheritance, through illustrations of her circumstances at different times during her life. -

Barrow Map Leaflet 28728 11/1/07 12:06 Page 1

Barrow Map Leaflet_28728 11/1/07 12:06 Page 1 Tel: 01229 474251. 01229 Tel: Tel: 01229 430600. 01229 Tel: WC u School. Riding Seaview specially trained owls/bird of prey. of owls/bird trained specially by the sea with sea the by horse a Ride Travelling to Barrow 835449. 01229 Tel: ASKAM from displays regular as well as diverse night life. life. night diverse - see a variety of owls of variety a see - owls Furness - IN - trails. waymarked BY CAR q and lively having for reputation countryside and seaside and countryside which adds further to the town’s the to further adds which From The M6 FURNESS 824334. 01229 Tel: the network of network the A595 Walk on board the Princess Selandia, Princess the board on Leave the Motorway at junction 36, then follow the A590 all the way to Barrow. restaurant. family and ROANHEAD LINDAL state of the art floating nightspot floating art the of state - indoor play area play indoor - BEACH Warehouse Wacky - IN - courses. excellent 3 Barrow’s is Barrow’s latest Barrow’s is From The Lakes Lagoon Blue The enthusiasts can play on play can enthusiasts Golf Take the A592 from Bowness along the Eastern shore of Lake Windermere. FURNESS A590 823823. 01229 Tel: Tel: 01229 823823 01229 Tel: Lazerzone. of Join the A590 which takes you straight to Barrow. t SOUTH LAKES WILD eatery. stylish and WC 470303. 01229 Tel: bar, childrens play area and venue and area play childrens bar, - indoor play area area play indoor - ANIMAL PARK Playzone West Kitesurfing. West - stylish eatery, stylish - BY TRAIN House Custom The railway and play areas. -

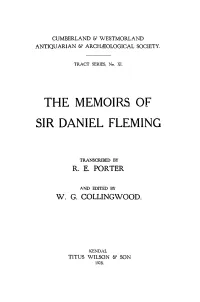

William Le Fleming, Richard Le Fleming &C

CUMBERLAND & WESTMORLAND ANTIQUARIAN & ARCHJEOLOGICAL SOCIETY. TRACT SERIES, No. XI. THE MEMOIRS OF SIR DANIEL FLEMING TRANSCRIBED BY R. E. PORTER AND EDITED BY W. G. COLLINGWOOD. KENDAL TITUS WILSON & SON 1928. KENDAL: PRINTED BY TITUS WILSON & SON, 28, Highgate. 1928. CONTENTS. PAGE... Editor's Preface Vll Sir Daniel Fleming, from the portrait at Rydal Hall . to /ace I The Earls of Flanders and the Flemings .. I Michael le Fleming of Furness .. 5 William f. Michael le Fleming and his family II Richard f. Michael le Fleming and the family of Beckermet . Richard f. John le Fleming and the family at Coniston and Beckermet . Thomas f. Thomas Fleming and the family at • Rydal and Coniston . 37 The Flemings of Conistori, Rydal and Skirwith · ... 56 William f. John Fleming, 1628-1649 .. 64 Daniel Fleming of Skirwith and his family 66 Sir Daniel Fleming, his autobiography 73 Description of Caernarvon Castle 81 Gleaston Castle .. 82 Coniston . 82 Rydal . 85 The arms belonging to the family of Fleming ~9 Sir Daniel Fleming's advice to his son 92 Appendix I ; Beckermet documents 98 Appendix II; Rydal documents .. I03 Appendix III ; Kirkland documents . Il2 Index . II8 EDITOR'S PREFACE. Our Society has already printed, in the Tract Series of which this volume is the latest, two short works by Sir Daniel Fleming of Rydal, his Surveys of Cumberland and of Westmorland. These Memoirs were long lost, and his own manuscript, if there was such in any complete form, is still unknown; but an early copy was found and transcribed by Mr. R. E. Porter, and with the leave of Stanley Hughes le Fleming Esq., of Rydal Hall, is now printed. -

Meeting of Urswick Parish Council

1094 MINUTES OF URSWICK, BARDSEA AND STAINTON PARISH COUNCIL From the meeting held on Thursday 20th April 2017 Urswick Parish Room, 7.30pm Present: Cllr. L. Birchall, Cllr. P. Bolt, Cllr. D. Chamberlain, Cllr. J. Keen (Chairman), Cllr. M. Turner, Dr. P. Attree (Clerk). District and County councillors: J. Willis. Members of the public: 1 1. To receive and approve apologies for absence. Apologies for absence were received from Cllrs. N. Cowsill, J. Hannah & J. Winder. Cllr. Bolt gave apologies for his late arrival. RESOLVED: that the apologies be noted and the reasons noted. 2. Declarations of interests To receive declarations by elected and co-opted members of interests in respect of items on this agenda. None. 3. Requests for dispensations None. 4. To authorise the Chairman to sign as a correct record the minutes of the meeting of the Council held on 9th March 2017. RESOLVED: that the minutes of the meeting held on 9th March 2017 be signed by the Chairman as a true record. 5. To note progress on matters not on today’s agenda – for report and observation only (items requiring a decision to be placed on agenda of next meeting). The Clerk reported on the following: • Nuisance smell from sileage stored at land adjacent to Daisy Hill Cottage, Great Urswick - reported to Public Protection Team and logged. • Potholes on lanes used as alternative routes during roadworks at Lindal in Furness. • Site of the former Coot, Great Urswick. Untidy site reported to District Council, and obstruction to traffic sightlines reported to County Highways. • Ongoing enquiries regarding Greenbank Gardens site, Little Urswick. -

Early Christian' Archaeology of Cumbria

Durham E-Theses A reassessment of the early Christian' archaeology of Cumbria O'Sullivan, Deirdre M. How to cite: O'Sullivan, Deirdre M. (1980) A reassessment of the early Christian' archaeology of Cumbria, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/7869/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk Deirdre M. O'Sullivan A reassessment of the Early Christian.' Archaeology of Cumbria ABSTRACT This thesis consists of a survey of events and materia culture in Cumbria for the period-between the withdrawal of Roman troops from Britain circa AD ^10, and the Viking settlement in Cumbria in the tenth century. An attempt has been made to view the archaeological data within the broad framework provided by environmental, historical and onomastic studies. Chapters 1-3 assess the current state of knowledge in these fields in Cumbria, and provide an introduction to the archaeological evidence, presented and discussed in Chapters ^--8, and set out in Appendices 5-10. -

Furness Abbey, Barrow-In- Furness, Cumbria

FURNESS ABBEY, BARROW-IN- FURNESS, CUMBRIA Archaeological Evaluation Oxford Archaeology North February 2011 English Heritage Issue No: 2010-11/1155 OA North Job No: L9833 NGR: SD 218 717 SMC Ref: S00001899 Furness Abbey, Barrow-in-Furness, Cumbria: Archaeological Evaluation 1 CONTENTS SUMMARY ..................................................................................................................3 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ..............................................................................................4 1. INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................................5 1.1 Circumstances of the Project .............................................................................5 1.2 Site Location, Topography and Geology............................................................5 1.3 Archaeological and Historical Background........................................................5 2. METHODOLOGY .....................................................................................................7 2.1 Project Design...................................................................................................7 2.2 Evaluation Trenching ........................................................................................7 2.3 Artefacts............................................................................................................7 2.4 Archive .............................................................................................................7 3. -

Appendix 3 Objections.Pdf

Prof. Jim D. Marshall Earth, Ocean and Ecological Sciences School of Environmental Sciences University of Liverpool 4 Brownlow Street Liverpool L69 3GP United Kingdom 0151--794 5177 Commons Registration Authority Cumbria County Council Application CA13/22 9 February 2019 To whom it may concern Urswick Tarn - Retention of Common Land Status. I am writing this letter to oppose application CA13/22 which seeks to remove the common land status assigned to the land associated with the former chapel at Urswick Tarn. My research group and I have long standing interests in Urswick Tarn and other marl lakes in Northwest England and have published many papers in international scientific journals on the significance of the sediment records that are preserved there. Starting with the work of Professor Frank Oldfield in the 1950’s and 60’s Urswick Tarn and its surrounding marl bench has been studied by scientists from Liverpool and many other Universities (including Exeter, Edge Hill and King’s College London). This is a site of national and indeed international scientific importance. The marl sediments beneath the chapel land and in the lake basin record the changing vegetation, land use and climate of the site spanning the 10,000 years and more since the end of the last glaciation. Marl lakes of this sort are relatively rare and provide a unique combination of biological remains and chemical markers than can be used to reconstruct past environmental change. My own specialisation, oxygen and carbon stable isotope geochemistry, enable us to quantitatively reconstruct past changes in temperature, rainfall and carbon cycling. -

The Experience of Early Friends

The Experience of Early Friends By Andrew Wright 2005 Historical Context The world of the early Friends was in the midst of radical change. The Renaissance in Europe had strengthened the role of science and reason in the Western world. The individual’s power to understand and make sense of reality on their own was challenging the authority of the Catholic Church. Until recently there had been only one church in Western Europe. Martin Luther’s “95 Theses” that critiqued the Catholic Church is generally seen as the beginning of the Reformation when western Christianity splintered into a plethora of various “protestant” churches. In order to fully understand the significance of the Reformation we must realize that political authority and religious authority were very closely aligned at this time in history. Political authority was used to enforce religious orthodoxy as well as to punish those who expressed unconventional views. Meditating on the intensity of feeling that many have today about issues like abortion or gay/ lesbian rights or end of life issues might begin to help us to understand the intensity of feeling that people experienced around religious issues during the Reformation. Many people felt like only the triumph of their religious group could secure their right to religious expression or save them from persecution. The notion of separation of church and state only began to become a possibility much later. The English Reformation and Civil War In England, the reformation developed a little later than in Germany and in a slightly different way. In 1534, King Henry VIII declared the Church of England independent of the Roman Catholic papacy and hierarchy. -

Full Proposal for Establishing a New Unitary Authority for Barrow, Lancaster and South Lakeland

Full proposal for establishing a new unitary authority for Barrow, Lancaster and South Lakeland December 2020 The Bay Council and North Cumbria Council Proposal by Barrow Borough Council, Lancaster City Council and South Lakeland District Council Foreword Dear Secretary of State, Our proposals for unitary local government in the Bay would build on existing momentum and the excellent working relationships already in place across the three district Councils in the Bay area. Together, we can help you deliver a sustainable and resilient local government solution in this area that delivers priority services and empowers communities. In line with your invitation, and statutory guidance, we are submitting a Type C proposal for the Bay area which comprises the geographies of Barrow, Lancaster Cllr Ann Thomson Sam Plum and South Lakeland councils and the respective areas of the county councils of Leader of the Council Chief Executive Cumbria and Lancashire. This is a credible geography, home to nearly 320,000 Barrow Borough Council Barrow Borough Council people, most of whom live and work in the area we represent. Having taken into account the impact of our proposal on other local boundaries and geographies, we believe creating The Bay Council makes a unitary local settlement for the remainder of Cumbria more viable and supports consideration of future options in Lancashire. Partners, particularly the health service would welcome alignment with their footprint and even stronger partnership working. Initial discussions with the Police and Crime Commissioners, Chief Officers and lead member for Fire and Cllr Dr Erica Lewis Kieran Keane Rescue did not identify any insurmountable barriers, whilst recognising the need Leader of the Council Chief Executive for further consultation. -

From Plainness to Simplicity: Changing Quaker Ideals for Material Culture J

Chapter 2 From Plainness to Simplicity: Changing Quaker Ideals for Material Culture J. William Frost Quakers or the Religious Society of Friends began in the 1650s as a response to a particular kind of direct or unmediated religious experience they described metaphorically as the discovery of the Inward Christ, Seed, or Light of God. This event over time would shape not only how Friends wor shipped and lived but also their responses to the peoples and culture around them. God had, they asserted, again intervened in history to bring salvation to those willing to surrender to divine guidance. The early history of Quak ers was an attempt by those who shared in this encounter with God to spread the news that this experience was available to everyone. In their enthusiasm for this transforming experience that liberated one from sin and brought sal vation, the first Friends assumed that they had rediscovered true Christianity and that their kind of religious awakening was the only way to God. With the certainty that comes from firsthand knowledge, they judged those who op posed them as denying the power of God within and surrendering to sin. Be fore 1660 their successes in converting a significant minority of other English men and women challenged them to design institutions to facilitate the ap proved kind of direct religious experience while protecting against moral laxity. The earliest writings of Friends were not concerned with outward ap pearance, except insofar as all conduct manifested whether or not the person had hearkened to the Inward Light of Christ. The effect of the Light de pended on the previous life of the person, but in general converts saw the Light as a purging as in a refiner’s fire (the metaphor was biblical) previous sinful attitudes and actions. -

Local Government Boundary Commission for England Report No

Local Government Boundary Commission For England Report No. 27 2 LOCAL GOVERNMENT BOUNDARY COMMISSION FOR ENGLAND REPORT NO. LOCAL GOVERNMENT BOUNDARY COMMISSION FOR ENGLAND CHAIRMAN Sir Edmund Compton GCB KBE DEPUTY CHAIRMAN Mr J M Rankin QC MEMBERS Lady Bowden Mr J T Brockbank Professor Michael Chisholm Mr R R Thornton CB DL Sir Andrew Vheatley CBE To the Ht Hon Merlyn Rees, MF Secretary of State for the Home Department PROPOSALS FOK FUTURE ULECTOHAL ARRANGEMENTS FOK THE SOUTH LAKELAND DISTRICT IN THE COUNTY Ot1 CUMBRIA 1. We, the Local Government Boundary Commission for England, having carried out our initial review of the electoral arrangements for South Lakeland district in accordance with the requirements of Section 63 of, and Schedule 9'to, the Local Government Act 1972, present our proposals for the future electoral arrangements for that district. 2. In accordance with the procedure laid down in Section 60(1) and (2) of the T972 Act, notice was given on 19 August 1974 that we were to undertake this review. This was incorporated in a consultation letter addressed to the South Lakeland District Council, copies of which were circulated to Cumbria County Council, parish councils and parish meetings in the district, the Members of Parliament for the constituencies concerned and the headquarters of the main political parties. Copies were also sent to the editors of local newspapers circulating in the area and of the local government press. Notices inserted in the local press announced the start of the review and invited comments from members of the public and from interested bodies.