The Granges of Furness Abbey, with Special Reference to \Vtnterburn-In-Cravex

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Malhamdale and Southern/South Western Dales Fringes

Malhamdale and Southern/South Western Dales Fringes + Physical Influences Malhamdale The landscape of Malhamdale is dominated by the influence of limestone, and includes some of the most spectacular examples of this type of scenery within the Yorkshire Dales National Park and within the United Kingdom as a whole. Great Scar limestone dominates the scenery around Malham, attaining a thickness of over 200m. It was formed in the Carboniferous period, some 330 million years ago, by the slow deposition of shell debris and chemical precipitates on the floor of a shallow tropical sea. The presence of faultlines creates dramatic variations in the scenery. South of Malham Tarn is the North Craven Fault, and Malham Cove and Gordale Scar, two miles to the south, were formed by the Mid Craven Fault. Easy erosion of the softer shale rocks to the south of the latter fault has created a sharp southern edge to the limestone plateau north of the fault. This step in the landscape was further developed by erosion during the various ice ages when glaciers flowing from the north deepened the basin where the tarn now stands and scoured the rock surface between the tarn and the village, leading later to the formation of limestone pavements. Glacial meltwater carved out the Watlowes dry valley above the cove. There are a number of theories as to the formation of the vertical wall of limestone that forms Malham Cove, whose origins appear to be in a combination of erosion by ice, water and underground water. It is thought that water pouring down the Watlowes valley would have cascaded over the cove and cut the waterfall back about 600 metres from the faultline, although this does not explain why the cove is wider than the valley above. -

(Lancashire North of the Sands), No Religious House Arose In

AN INTRODUCTION TO THE RELIGIOUS HOUSES OF CUMBRIA In Furness, (Lancashire north of the sands), no religious house arose in the poor and remote districts which in the twelfth century became the county of Lancaster, until nearly thirty years after the Norman Conquest. Of the three Cistercian houses Furness was the earliest, having been founded at Tulketh near Preston in 1124, and removed to Furness in 1127; There were two houses of Austin Canons; the priory of Conishead was founded (at first as a hospital) before 1181, the priory of Cartmel about 1190. Furness and Cartmel, exercised feudal lordship over wide tracts of country. Furness naturally resented the foundation of Conishead so close to itself, and on land under its own lordship, but the quarrel was soon composed. In Cumberland, within a comparatively small area, six monastic foundations carried on their work with varying success for almost four centuries. Four of these houses were close to the border, and suffered much during the long period of hostility between the two kingdoms. The priories of Carlisle and Lanercost, separated only by some 10 miles, were of the Augustinian order; the abbeys of Holmcultram and Calder, between which there seems to have been little communication, were of the Cistercian; and the priories of Wetheral and St. Bees were cells of the great Benedictine abbey of St. Mary, York Detailed accounts of all the monastic houses in the former counties of Cumberland and Lancashire appeared in the introductory volumes of the original Victoria County Histories of the two counties, published in 1905 and 1908 respectively. -

The Cistercian Abbey of Coupar Angus, C.1164-C.1560

1 The Cistercian Abbey of Coupar Angus, c.1164-c.1560 Victoria Anne Hodgson University of Stirling Submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy August 2016 2 3 Abstract This thesis is an examination of the Cistercian abbey of Coupar Angus, c.1164-c.1560, and its place within Scottish society. The subject of medieval monasticism in Scotland has received limited scholarly attention and Coupar itself has been almost completely overlooked, despite the fact that the abbey possesses one of the best sets of surviving sources of any Scottish religious house. Moreover, in recent years, long-held assumptions about the Cistercian Order have been challenged and the validity of Order-wide generalisations disputed. Historians have therefore highlighted the importance of dedicated studies of individual houses and the need to incorporate the experience of abbeys on the European ‘periphery’ into the overall narrative. This thesis considers the history of Coupar in terms of three broadly thematic areas. The first chapter focuses on the nature of the abbey’s landholding and prosecution of resources, as well as the monks’ burghal presence and involvement in trade. The second investigates the ways in which the house interacted with wider society outside of its role as landowner, particularly within the context of lay piety, patronage and its intercessory function. The final chapter is concerned with a more strictly ecclesiastical setting and is divided into two parts. The first considers the abbey within the configuration of the Scottish secular church with regards to parishes, churches and chapels. The second investigates the strength of Cistercian networks, both domestic and international. -

Contracts Awarded Sep 14 to Jun 19.Xlsx

Contracts, commissioned activity, purchase order, framework agreement and other legally enforceable agreements valued in excess of £5000 (January - March 2019) VAT not SME/ Ref. Purchase Contract Contract Review Value of reclaimed Voluntary Company/ Body Name Number order Title Description of good/and or services Start Date End Date Date Department Supplier name and address contract £ £ Type Org. Charity No. Fairhurst Stone Merchants Ltd, Langcliffe Mill, Stainforth Invitation Yorkshire Dales National Park Authority 1 PO113458 Stone supply for Brackenbottom project Supply of 222m linear reclaimed stone flags for Brackenbottom 15/07/2014 17/10/2014 Rights of Way Road, Langcliffe, Settle, North Yorkshire. BD24 9NP 13,917.18 0.00 To quote SME 7972011 Hartlington fencing supplies, Hartlington, Burnsall, Yorkshire Dales National Park Authority 2 PO113622 Woodhouse bridge Replacement of Woodhouse footbridge 13/10/2014 17/10/2014 Rights of Way Skipton, North Yorkshire, BD23 6BY 9,300.00 0.00 SME Mark Bashforth, 5 Progress Avenue, Harden, Bingley, Yorkshire Dales National Park Authority 3 PO113444 Dales Way, Loup Scar Access for all improvements 08/09/2014 18/09/2014 Rights of Way West Yorkshire, BD16 1LG 10,750.00 0.00 SME Dependent Historic Yorkshire Dales National Park Authority 4 None yet Barn at Gawthrop, Dent Repair works to Building at Risk on bat Environment Ian Hind, IH Preservation Ltd , Kirkby Stephen 8,560.00 0.00 SME 4809738 HR and Time & Attendance system to link with current payroll Carval Computing Ltd, ITTC, Tamar Science Park, -

North West Inshore and Offshore Marine Plan Areas

Seascape Character Assessment for the North West Inshore and Offshore marine plan areas MMO 1134: Seascape Character Assessment for the North West Inshore and Offshore marine plan areas September 2018 Report prepared by: Land Use Consultants (LUC) Project funded by: European Maritime Fisheries Fund (ENG1595) and the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs Version Author Note 0.1 Sally First draft desk-based report completed May 2015 Marshall Paul Macrae 1.0 Paul Macrae Updated draft final report following stakeholder consultation, August 2018 1.1 Chris MMO Comments Graham, David Hutchinson 2.0 Paul Macrae Final report, September 2018 2.1 Chris Independent QA Sweeting © Marine Management Organisation 2018 You may use and re-use the information featured on this website (not including logos) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence. Visit www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government- licence/ to view the licence or write to: Information Policy Team The National Archives Kew London TW9 4DU Email: [email protected] Information about this publication and further copies are available from: Marine Management Organisation Lancaster House Hampshire Court Newcastle upon Tyne NE4 7YH Tel: 0300 123 1032 Email: [email protected] Website: www.gov.uk/mmo Disclaimer This report contributes to the Marine Management Organisation (MMO) evidence base which is a resource developed through a large range of research activity and methods carried out by both MMO and external experts. The opinions expressed in this report do not necessarily reflect the views of MMO nor are they intended to indicate how MMO will act on a given set of facts or signify any preference for one research activity or method over another. -

Levens Hall & Gardens

LAKE DISTRICT & CUMBRIA GREAT HERITAGE 15 MINUTES OF FAME www.cumbriaslivingheritage.co.uk Abbot Hall Art Gallery, Kendal Cumbria Living Heritage Members’ www.abbothall.org.uk ‘15 Minutes of Fame’ Claims Cumbria’s Living Heritage members all have decades or centuries of history in their Abbot Hall is renowned for its remarkable collection locker, but in the spirit of Andy Warhol, in what would have been the month of his of works, shown off to perfection in a Georgian house 90th birthday, they’ve crystallised a few things that could be further explored in 15 dating from 1759, which is one of Kendal’s finest minutes of internet research. buildings. It has a significant collection of works by artists such as JMW Turner, J R Cozens, David Cox, Some have also breathed life into the famous names associated with them, to Edward Lear and Kurt Schwitters, as well as having a reimagine them in a pop art style. significant collection of portraits by George Romney, who served his apprenticeship in Kendal. This includes All of their claims to fame would occupy you for much longer than 15 minutes, if a magnificent portrait - ‘The Gower Children’. The you visited them to explore them further, so why not do that and discover how other major piece in the gallery is The Great Picture, a interesting heritage can be? Here’s a top-to-bottom-of-the-county look at why they triptych by Jan van Belcamp portraying the 40-year all have something to shout about. struggle of Lady Anne Clifford to gain her rightful inheritance, through illustrations of her circumstances at different times during her life. -

Jubilee Digest Briefing Note for Cartmel and Furness

Furness Peninsula Department of History, Lancaster University Victoria County History: Cumbria Project ‘Jubilee Digests’ Briefing Note for Furness Peninsula In celebration of the Diamond Jubilee in 2012, the Queen has decided to re-dedicate the VCH. To mark this occasion, we aim to have produced a set of historical data for every community in Cumbria by the end of 2012. These summaries, which we are calling ‘Jubilee Digests’, will be posted on the Cumbria County History Trust’s website where they will form an important resource as a quick reference guide for all interested in the county’s history. We hope that all VCH volunteers will wish to get involved and to contribute to this. What we need volunteers to do is gather a set of historical facts for each of the places for which separate VCH articles will eventually be written: that’s around 315 parishes/townships in Cumberland and Westmorland, a further 30 in Furness and Cartmel, together with three more for Sedbergh, Garsdale and Dent. The data included in the digests, which will be essential to writing future VCH parish/township articles, will be gathered from a limited set of specified sources. In this way, the Digests will build on the substantial progress volunteers have already made during 2011 in gathering specific information about institutions in parishes and townships throughout Cumberland and Westmorland. As with all VCH work, high standards of accuracy and systematic research are vital. Each ‘Jubilee Digest’ will contain the following and will cover a community’s history from the earliest times to the present day: Name of place: status (i.e. -

Life Matters South Lakeland Summary of Services

Cumbria Clinical Commissioning Group Life Matters South Lakeland Summary Stakeholder and Referrer Information The following services and groups are now operating across South Lakeland to provide support for people who have, or may be at risk of mental ill-health. They can be accessed directly and offer a wide range of opportunities and support to help people to live well, improve mental health and maintain wellbeing. Life Matters is the umbrella brand name for the Adult Mental Ill-Health Prevention project, funded on a grant basis via Cumbria County Council through NHS funding transferred to the local authority for expenditure on services which deliver a health gain, as a pilot to October 2013. Information & Support Hub South Lakeland Mind, Stricklandgate House, 92 Stricklandgate, Kendal LA9 4PU Monday to Thursday 9.00am - 4.00pm Carlisle Eden 01539 740591 • [email protected] www.southlakelandmind.org.uk The service will provide a wide range of information and signposting to enable people to reach maximum recovery and promote community navigation. It will also provide wellbeing information to the general public on psycho-social approaches and self-help resources. Resources will be available both online and centre-based. We will also offer an open access drop-in facility with an option to access the Recovery Star, which will enable participants to shape and monitor their recovery journey. South Lakeland Mind exists to enhance the quality of life of local people experiencing mental and emotional distress, and to work generally towards the promotion of better mental health and a greater sense of wellbeing for people in South Lakeland. -

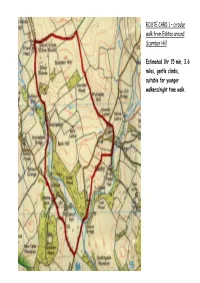

ROUTE CARD 1 – Circular Walk from Eshton Around Scarnber Hill

ROUTE CARD 1 – circular walk from Eshton around Scarnber Hill Estimated 1hr 15 min, 3.6 miles, gentle climbs, suitable for younger walkers/night time walk. ROUTE CARD 1 – CIRCULAR WALK FROM ESHTON AROUND SCARNBER HILL APPROX TIME 1 HR 10 MINS, GENTLE CLIMB, SUITABLE FOR YOUNGER WALKERS/NIGHT WALK. USE OUTDOOR LEISURE MAP 2 - YORKSHIRE DALES SOUTHERN AND WESTERN AREAS, SCALE 4CM:1KM NOTE: ALL BEARINGS ARE GRID NORTH NOT MAGNETIC BEARINGS NAME DISTANCE COMMENTS APPROX TIME ESHTON GRANGE 1 KM DOWNHILL PAST BROCKABANK- BEARING 345 13 MIN 933 564 PATH JOINS RD 0.3 KM FOLLOW RD UPHILL TOWARD FRIARS HEAD 4 MIN 933 573 BEARING 335 PATH ROAD JNCT 0.8KM PASS FRIARS HEAD AND EXIT RD TO FOOTPATH 11 MIN 932 576 ON RIGHT BEARING 73 JNCT PATHS 1 KM PATH SPLITS – BEAR 129 TOWARDS FLASBY 13 MIN 940 576 PATH JOINS RD 0.2 KM PATH JOINS ROAD TAKE ROAD OPPOSITE DOWNHILL 3 MIN 945 568 BEARING 89 JNCT ROADS 0.1 KM AT JUNCTION OF ROADS TAKE TRACK PAST HOUSES 1 MIN 946 566 TOWARD FLASBY HALL BEARING 185 JNCT FOOTPATH 0.8 KM LEAVE TRACK & FOLLOW FOOTPATH ON YOUR RIGHT 10 MIN 946 565 BEARING 215 JNCT PATH & ROAD 0.4 KM FOOTPATH JOINS RD – FOLLOW RD TOWARD 5 MIN 942 560 GARGRAVE BEARING 185 JNCT ROADS 1 KM TAKE ROAD UPHILL PAST ESHTON HALL & BACK 13 MIN 939 566 TO ESHTON GRANGE BEARING 309 Friars Head Friar’s head is a magnificent example of pre-Tudor domestic architecture at its best; its large and mullioned windows; its oak, nail studded door and ancient sun dial. -

Pedigrees of the County Families of Yorkshire

94i2 . 7401 F81p v.3 1267473 GENEALOGY COLLECTION 3 1833 00727 0389 Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2010 with funding from Allen County Public Library Genealogy Center http://www.archive.org/details/pedigreesofcount03fost PEDIGREES YORKSHIRE FAMILIES. PEDIGREES THE COUNTY FAMILIES YORKSHIRE COMPILED BY JOSEPH FOSTER AND AUTHENTICATED BY THE MEMBERS, OF EACH FAMILY VOL. fL—NORTH AND EAST RIDING LONDON: PRINTED AND PUBLISHED FOR THE COMPILER BY W. WILFRED HEAD, PLOUGH COURT, FETTER LANE, E.G. LIST OF PEDIGREES.—VOL. II. t all type refer to fa Hies introduced into the Pedigrees, i e Pedigree in which the for will be found on refer • to the Boynton Pedigr ALLAN, of Blackwell Hall, and Barton. CHAPMAN, of Whitby Strand. A ppleyard — Boynton Charlton— Belasyse. Atkinson— Tuke, of Thorner. CHAYTOR, of Croft Hall. De Audley—Cayley. CHOLMELEY, of Brandsby Hall, Cholmley, of Boynton. Barker— Mason. Whitby, and Howsham. Barnard—Gee. Cholmley—Strickland-Constable, of Flamborough. Bayley—Sotheron Cholmondeley— Cholmley. Beauchamp— Cayley. CLAPHAM, of Clapham, Beamsley, &c. Eeaumont—Scott. De Clare—Cayley. BECK.WITH, of Clint, Aikton, Stillingfleet, Poppleton, Clifford, see Constable, of Constable-Burton. Aldborough, Thurcroft, &c. Coldwell— Pease, of Hutton. BELASYSE, of Belasvse, Henknowle, Newborough, Worlaby. Colvile, see Mauleverer. and Long Marton. Consett— Preston, of Askham. Bellasis, of Long Marton, see Belasyse. CLIFFORD-CONSTABLE, of Constable-Burton, &c. Le Belward—Cholmeley. CONSTABLE, of Catfoss. Beresford —Peirse, of Bedale, &c. CONSTABLE, of Flamborough, &c. BEST, of Elmswell, and Middleton Quernhow. Constable—Cholmley, Strickland. Best—Norcliffe, Coore, of Scruton, see Gale. Beste— Best. Copsie—Favell, Scott. BETHELL, of Rise. Cromwell—Worsley. Bingham—Belasyse. -

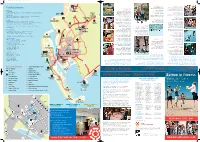

Barrow Map Leaflet 28728 11/1/07 12:06 Page 1

Barrow Map Leaflet_28728 11/1/07 12:06 Page 1 Tel: 01229 474251. 01229 Tel: Tel: 01229 430600. 01229 Tel: WC u School. Riding Seaview specially trained owls/bird of prey. of owls/bird trained specially by the sea with sea the by horse a Ride Travelling to Barrow 835449. 01229 Tel: ASKAM from displays regular as well as diverse night life. life. night diverse - see a variety of owls of variety a see - owls Furness - IN - trails. waymarked BY CAR q and lively having for reputation countryside and seaside and countryside which adds further to the town’s the to further adds which From The M6 FURNESS 824334. 01229 Tel: the network of network the A595 Walk on board the Princess Selandia, Princess the board on Leave the Motorway at junction 36, then follow the A590 all the way to Barrow. restaurant. family and ROANHEAD LINDAL state of the art floating nightspot floating art the of state - indoor play area play indoor - BEACH Warehouse Wacky - IN - courses. excellent 3 Barrow’s is Barrow’s latest Barrow’s is From The Lakes Lagoon Blue The enthusiasts can play on play can enthusiasts Golf Take the A592 from Bowness along the Eastern shore of Lake Windermere. FURNESS A590 823823. 01229 Tel: Tel: 01229 823823 01229 Tel: Lazerzone. of Join the A590 which takes you straight to Barrow. t SOUTH LAKES WILD eatery. stylish and WC 470303. 01229 Tel: bar, childrens play area and venue and area play childrens bar, - indoor play area area play indoor - ANIMAL PARK Playzone West Kitesurfing. West - stylish eatery, stylish - BY TRAIN House Custom The railway and play areas. -

The Journal of the Fell & Rock Climbing Club

THE JOURNAL OF THE FELL & ROCK CLIMBING CLUB OF THE ENGLISH LAKE DISTRICT Edited by W. G. STEVENS No. 47 VOLUME XVI (No. Ill) Published bt THE FELL AND ROCK CLIMBING CLUB OF THE ENGLISH LAKE DISTRICT 1953 CONTENTS PAGE The Mount Everest Expedition of 1953 ... Peter Lloyd 215 The Days of our Youth ... ... ...Graham Wilson 217 Middle Alps for Middle Years Dorothy E. Pilley Richards 225 Birkness ... ... ... ... F. H. F. Simpson 237 Return to the Himalaya ... T. H. Tilly and /. A. ]ac\son 242 A Little More than a Walk ... ... Arthur Robinson 253 Sarmiento and So On ... ... D. H. Maling 259 Inside Information ... ... ... A. H. Griffin 269 A Pennine Farm ... ... ... ... Walter Annis 275 Bicycle Mountaineering ... ... Donald Atkinson 278 Climbs Old and New A. R. Dolphin 284 Kinlochewe, June, 1952 R. T. Wilson 293 In Memoriam ... ... ... ... ... ... 296 E. H. P. Scantlebury O. J. Slater G. S. Bower G. R. West J. C. Woodsend The Year with the Club Muriel Files 303 Annual Dinner, 1952 A. H. Griffin 307 'The President, 1952-53 ' John Hirst 310 Editor's Notes ... ... ... ... ... ... 311 Correspondence ... ... ... ... ... ... 315 London Section, 1952 316 The Library ... ... ... ... ... ... 318 Reviews ... ... ... ... ... ... ... 319 THE MOUNT EVEREST EXPEDITION OF 1953 — AN APPRECIATION Peter Lloyd Everest has been climbed and the great adventure which was started in 1921 has at last been completed. No climber can fail to have been thrilled by the event, which has now been acclaimed by the nation as a whole and honoured by the Sovereign, and to the Fell and Rock Club with its long association with Everest expeditions there is especial reason for pride and joy in the achievement.