A Map to Paradise Road: a Guide for Historians

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Issue125 – Jan 2016

CASCABEL Journal of the ROYAL AUSTRALIAN ARTILLERY ASSOCIATION (VICTORIA) INCORPORATED ABN 22 850 898 908 ISSUE 125 Published Quarterly in JANUARY 2016 Victoria Australia Russian 6 inch 35 Calibre naval gun 1877 Refer to the Suomenlinna article on #37 Article Pages Assn Contacts, Conditions & Copyright 3 The President Writes & Membership Report 5 From The Colonel Commandant + a message from the Battery Commander 6 From the Secretary’s Table 7 A message from the Battery Commander 2/10 Light Battery RAA 8 Letters to the Editor 11 Tradition Continues– St Barbara’s Day Parade 2015 (Cont. on page 51) 13 My trip to the Western Front. 14 Saint Barbara’s Day greeting 15 RAA Luncheon 17 Broome’s One Day War 18 First to fly new flag 24 Inspiring leadership 25 Victoria Cross awarded to Lance Corporal for Afghanistan rescue 26 CANADIAN tribute to the results of PTSD. + Monopoly 27 Skunk: A Weapon From Israel + Army Remembrance Pin 28 African pouched rats 29 Collections of engraved Zippo lighters 30 Flying sisters take flight 31 A variety of links for your enjoyment 32 New grenade launcher approved + VALE Luke Worsley 33 Defence of Darwin Experience won a 2014 Travellers' Choice Award: 35 Two Hundred and Fifty Years of H M S Victory 36 Suomenlinna Island Fortress 37 National Gunner Dinner on the 27th May 2017. 38 WHEN is a veteran not a war veteran? 39 Report: British Sniper Saves Boy, Father 40 14th Annual Vivian Bullwinkel Oration 41 Some other military reflections 42 Aussies under fire "like rain on water" in Afghan ambush 45 It’s something most of us never hear / think much about.. -

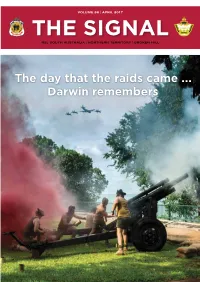

The Day That the Raids Came ... Darwin Remembers RSL CARE SA

VOLUME 86 | APRIL 2017 R E T E U U R G N A E E D L & SERVICES A F F I LI AT E RSL SOUTH AUSTRALIA | NORTHERN TERRITORY | BROKEN HILL The day that the raids came ... Darwin remembers RSL CARE SA RSL Care SA, providing a range of care and support services for the ex-service and veteran community. RSL Care SA has extensive experience and understanding of DVA and the implications of DVA entitlements entering residential aged care. For many people, considering nursing home aged care can be a stressful time. Our friendly admissions team is available to help guide you through the process and answer questions you may have. The Australian Government has strong protections in place to ensure that care is affordable for everyone and also subsidises a range of aged care services in Australia. Our nursing homes or residential aged care facilities offer short-term respite care or permanent care options. RSL Care SA has care facilities in Myrtle Bank and Angle Park. The War Veterans’ Home (WVH) is located in Myrtle Bank only 4kms from the CBD and is home to 95 residents. RSL Villas are situated next to Remembrance Park in Angle Park, 9kms north-west of the city. If you would like more information regarding residential aged care, the implications of DVA payments in aged care or to be considered for a place in one of our facilities, please call our admissions team on 08 8379 2600. For more information visit our website www.rslcaresa.com.au or www.myagedcare.gov.au War Veterans’ Home RSL Villas 55 Ferguson Avenue, Myrtle Bank SA 5064 18 Trafford Street, -

Trent Burnard Trent Burnard Lieutenant Colonel Commanding Officer 10Th/27Th Battalion, the Royal South Australia Regiment

Official Newsletter of the Royal South Australia Regiment Association Inc Editor - David Laing 0407 791 822 MARCH 2017 Inside this issue: Association BBQ Support for the Battalion Darwin - 75 Years Ago 2 About 4 weeks ago Rodney Beames received a mid week telephone call from the CO of 10/27 Bn RSAR requesting catering support for a Battalion Leadership Week- LETTERS 3 end at Keswick Barracks. “No problem!” said Beamsey, “When is it?” he asked, an- ticipating about a 10 day lead. “This weekend!” said the CO! CPL Davo’s page 4 How could Rod say anything but “How many are we feeding and what times are they dining?” How To Contact Us 5 Once that was worked out, Rod got on the phone to some members and got a reli- able, well oiled (in more ways than one) crew together, to provide sustenance for up The Radji Beach 6/7 Massacre 1942 to 30 Officers and Other Ranks attending the Leadership Exercise. The RSARA crew were present on both days to ensure the soldiers were well fed, ANZAC Day plan 8 and the fact that there was very little wastage showed how much the Diggers en- joyed the food. (See letter below.) One of our own from 9 the 10th Bn AIF Rod wishes to thank Nat Cooke, Mick Standing, Russ Durdin and Norm Rathmann, and of course Mrs Cheryl Beames who all made the support successful. Again! Members List 10 Purple & Blue Brothers 11 12 Letter of Appreciation Mr Rod Beames President Royal South Australia Regiment Association Inc Dear Rod LETTER OF APPRECIATION - SUPPORT TO 10/27 BN RSAR LEADERSHIP WEEKEND I would like to express my warmest thanks to you and your team for the support you provided to the Battalion Command Team with the provision of the lunchtime BBQ’s on our recent training weekend. -

Training, Ethos, Camaraderie and Endurance of World War Two Australian POW Nurses

Training, ethos, camaraderie and endurance of World War Two Australian POW nurses By Sarah Fulford 1 Contents Page Chapter 1: Introduction ..................................................................................... 3 Chapter 2: Historical framework ...................................................................... 13 Chapter 3: The Historical Context of Australian Nursing .................................. 32 Chapter 4: The Nurses at War – World War Two ............................................. 43 Chapter 5: Ethos .............................................................................................. 61 Chapter 6: Camaraderie ................................................................................... 83 Chapter 7: Resourcefulness ........................................................................... 113 Chapter 8: Conclusion .................................................................................... 141 Appendices: Appendix 1: AANS Pledge of Service .............................................................. 144 Appendix 2: Images of the Nurses in Malaya ................................................. 145 Appendix 3: Vyner Brooke Nurses ................................................................. 153 Appendix 4: Image of the Vyner Brooke and maps showing the movement of nurses during internment .............................................................................. 155 Appendix 5: Drawings by POWS during internment ...................................... 158 Appendix 6: “The -

The Story of 13

THE STORY OF 13th AUSTRALIAN GENERAL HOSPITAL 8th DIVISION 2nd A. I. F. 1941 – 1945 This un-official history of the 13 Australian General Hospital during WW2 was written by A.C. (Lex) Arthurson VX61276 who was a Corporal in the unit. It was prompted by former POW nurse Vivian Bullwinkel asking if the history had ever been written. Lex undertook to do it. With the assistance of others, it was completed over two years. The original document was enhanced by many newspaper cutting, pictures and sketches. It was not possible to reproduce these. Some alternative images have been inserted. (Most of the sketches inserted into the story were done by Corporal Dick Cochran 2/12 Field Company (Engineers) and provided to me by Ken Gray former National President ex POWs Association). I am grateful to Lex for permission to reproduce this history. It is pleasing to note the extensive (and rightful) coverage given to the Nurses in this history. Lt Col (Ret’d)Peter Winstanley OAM RFD (JP) May 2009 LIVES OF GREAT MEN ALL REMIND US WE CAN LIVE A LIFE SUBLIME AND, DEPARTING, LEAVE BEHIND US FOOTPRINTS IN THE SANDS OF TIME. QUATRAIN OF LONGFELLOW FROM “The Psalm of Life” Acknowledgements: Official Army Records Newspapers of 1945 - Melbourne Herald 1945 - Melbourne Age 1942 - Singapore Straits Times Special thanks to Mrs. Maureen Chandler for the loan of her father’s unique records of the 13th A.G.H. from 1941 – 1945. (Staff/Sgt. Pearce Wells was privy to all hospital records.) _________________________ Mrs Connie Cooper who loaned the diary of her husband, Staff/Sgt. -

Secrets & Spies Research Dossier

SECRETS & SPIES RESEARCH DOSSIER By ERSKINE PARK HIGH SCHOOL AUSTRALIA Andre Bernardino, Marc Graham, Umair Khan, Isaac Lim, Baylie Luke, Zack Lynch, Govind Mallath, Tyrone Myburgh-Sisam, Benjamin Tatlock, Lance Woodgate How Prisoners of War used secrecy to gain intelligence about the war, to communicate with the outside world and other camps, and to boost morale Introduction This report covers the ways Prisoners of War (POWs) used secrecy to gain intelligence about the war, to communicate with the outside world and to boost morale. The main focus point will be on Changi POW camp and the Thai Burma Railway, as this is the majority of experiences of ANZAC POWs in the Pacific. Changi was a harsh POW camp that held over 13,000 Australian POWs, and the majority of those were not treated well. The camp was unsanitary, there was a lack of food, a lack of doctors, and a severely large amount of death. They needed a way to send messages in an out of the camp so they could learn the news, but the camp did not allow conventional ways of communication to and from the camp. Therefore, they used strange ways to send secret messages from the camp. Our group, during this endeavor, also interviewed World War Two veteran David Trist. This interview gave us an insight in capturing Japanese POWs and how they were treated. He told us a story about himself, a guard, sharing a cigarette with a Japanese soldier, which we found really enlightening. 1 Impacts and experiences on Australian P.O.W Soldiers Over 22,000 Australian servicemen and almost forty nurses were captured by the Japanese. -

Sisters Behind the Wire: Reappraising Australian Military Nursing and Internment in the Pacific During World War II

Medical History, 2011, 55: 419–424 Sisters Behind the Wire: Reappraising Australian Military Nursing and Internment in the Pacific during World War II ANGHARAD FLETCHER* Keywords: Australian Military Nursing; Second World War; Internment; Pacific During the Second World War, approximately 3,500 Australian military nurses served in combat regions throughout the world. The vast majority were enlisted in the Austra- lian Army Nursing Service (AANS), but after the Japanese advance and the fall of Hong Kong (December 1941) and Singapore (February 1942), a significant number of these nurses spent three-and-a-half years as POWs in Indonesia, Hong Kong, Japan and the Philippines.1 To date, considerable research has been undertaken on POW experiences in Hong Kong, Singapore, Thailand and Japan, albeit primarily focused on the testimonies of men and civilian women.2 This body of research utilises various methodologies, from Yuki Tanaka and Kei Ushimura’s efforts to reconcile Japanese war crimes with the corruption of the Bushido ethic and sexual violence in contempor- ary Japanese society, to Christina Twomey’s work on the imprisonment and repatria- tion of Dutch, Dutch–Eurasian and Australian civilian women and children. In the past fifteen years, historians have become aware of the need to recognise the multipli- city of these experiences, rather than continuing to focus on individual community, camp or regional case studies.3 Nurses are by no means absent from the discussion, although the majority of notable works on this subject focus on Hong Kong or the Ó Angharad Fletcher, 2011. written by interned nurses include Betty Jeffrey, White Coolies (London: Angus and Robertson, 1954) * Angharad Fletcher, MPhil student, Department of and Jessie Elizabeth Simons, While History Passed History, MB160, Main Building, University of (London: William Heinemann, 1954). -

Bangka Strait Memorial Service

Bangka Day Memorial Service 2015 Sunday 15 February 2015 Sue Newton, Jenny Hughes, Evonne Tylor and I attended the Memorial Service held at the South Australian Women’s Memorial Playing Fields, St Marys, in honour Army Nursing sisters massacred at Bangka Island on 16 February 1942. Bangka Strait Memorial Service On February 16th, 1942, 22 Australian Army Nurses were machine gunned by soldiers of the Imperial Japanese Army on Bangka Island's Radji Beach in the Dutch East Indies (now known as Indonesia). All but one nurse were killed in the massacre. Five years later, the lone survivor, Vivian Bullwinkel, gave evidence at a war crimes trial in Tokyo, having survived the war. Thirteen years after the massacre, the first Bangka Strait Memorial Service was held at the South Australian Women's Playing Fields and has been held annually on the Sunday closest to 16th February. The memorial service has expanded its scope of commemoration to Australian women who served their country overseas in the armed forces. It was to be a very hot day; luckily there was plenty of cover, with chairs to sit on and the committee providing all those present with cold drinking water throughout the service. This was my first experience and representing the members of the Region of South Australia was a privilege. The service was very moving and there were many organisations that paid their respects with the laying of wreaths, donations of books and money in front of the memorial plaque. The address was by author Ian W. Shaw who wrote the book ‘On Radji Beach’ and spoke of his research in the country regions of South Australia and the many untold stories of those who served in our Australian Forces. -

Sister Betty Jeffrey

Sister Betty Jeffrey We are praying for our freedom. If this doesn’t happen soon we shall be a mess for the rest of our lives. Betty Jeffrey, White coolies: a graphic record of survival in World War Two, Angus and Robertson, North Ryde, NSW, 1997, p. 148. Captain Vivian Bullwinkel (left) and Lieutenant Betty Jeffrey at a dedication ceremony to the fallen of the Second World War, 1950. AWM P04585.001 Agnes Betty Jeffrey Agnes Betty Jeffrey was born in Hobart on 14 May 1908, the second youngest child of six. As a child, Betty and her family moved often because of her father’s job. An accountant at the General Post Office, he was often transferred interstate. Agnes came to dislike her first name, preferring to be called Betty. After many years of travelling, the family finally settled in East Malvern, Victoria, the town Jeffrey would call home for the rest of her life. As part of a large family, she was surrounded by the singing and laughter of her siblings. She quickly learnt how to make clothing and food spread a little further, and knew what it This document is available on the Australian War Memorial’s website at http://www.awm.gov.au/education/resources/nurses You may download, display, print and reproduce this worksheet only for your personal, educational, non-commercial use or for use within your organisation, provided that you attribute the Australian War Memorial. meant to “do your bit”. She didn’t realise that the basic life skills she had learned as a child would one day help to save her life. -

Gala Dinner Honours Great Australian from the Head of School

Nursing and Midwifery News Issue 11, October 2006 Gala dinner honours great Australian More than 400 people enjoyed an evening of entertainment, fine food and wine at a gala dinner to honour Australian World War II heroine Vivian Bullwinkel and to raise funds for the Vivian Bullwinkel Memorial Fund. The memorial fund supports the work being undertaken by the Vivian Bullwinkel Chair in Palliative Care Nursing, which was established in 2003 by the School of Nursing and Midwifery at the Peninsula campus to lead research, teaching and support in the field of palliative care. Former Chief of Defence, General Peter Cosgrove AC MC, Professor O’Connor, Governor of Victoria Professor David Vivian Bullwinkel survived three years De Kretser AO, Faculty of Medicine, Nursing and Health Sciences’ Deputy Dean, Professor Leon Piterman, Ms Ita Buttrose AM and Vivian’s nephew Mr John Bullwinkel at the gala event. of captivity under the Japanese Imperial Forces during World War II. Following the war she continued to dedicate her life to the comfort of the sick and dying through her profession of nursing. From the Head of School The current Chair in Nursing, Palliative Care Despite the hectic pace of 2006 we are finding it difficult to afford postgraduate is held by Professor Margaret O’Connor all looking forward to next year, with the study. who has made an impressive 20 year introduction of two new awards at our Researchers within the School have contribution to the field to date and leads an Peninsula campus. The double degree been fortunate to attract a number of accomplished team of researchers. -

Bangka Island: the WW2 Massacre and a 'Truth Too Awful to Speak' by Gary Nunn Sydney • 18 April 2019

Bangka Island: The WW2 massacre and a 'truth too awful to speak' By Gary Nunn Sydney • 18 April 2019 Share this with Facebook • Share this with Messenger • Share this with Twitter • Share this with Email • • Share Related Topics • World War Two Image copyrightLYNETTE SILVERImage captionVivian Bullwinkel was the sole survivor of the Bangka Island massacre In 1942, a group of Australian nurses were murdered by Japanese soldiers in what came to be known as the Bangka Island massacre. Now, a historian has collated evidence indicating they were sexually assaulted beforehand - and that Australian authorities allegedly hushed it up. "It took a group of women to uncover this truth - and to finally speak it." Military historian Lynette Silver is discussing what happened to 22 Australian nurses who were marched into the sea at Bangka Island, Indonesia, and shot with machine guns in February 1942. All except one were killed. "That was a jolt to the senses enough. But to have been raped beforehand was just too awful a truth to speak," Ms Silver says, speaking of claims she details in a new book. "Senior Australian army officers wanted to protect grieving families from the stigma of rape. It was seen as shameful. Rape was known as a fate worse than death, and was still a hangable offence [for perpetrators] in New South Wales until 1955." The sole survivor Nurse Vivian Bullwinkel was shot in the massacre but survived by playing dead. She hid in the jungle and was taken as a prisoner of war, before eventually returning to Australia. Image copyrightGETTY IMAGESImage captionBangka Island lies off Sumatra in the Indonesian archipelago She was "gagged" from speaking about the rapes at the Tokyo war crimes tribunal in the aftermath of World War Two, according to Ms Silver, who researched an account Ms Bullwinkel gave to a broadcaster before she died in 2000. -

My Story of Aunt, Clarice Isobel Halligan

P a g e | 1 My story of Aunt, Clarice Isobel Halligan By her niece, Lorraine Clarice Curtis (nee Halligan) born on 6th January, 1943, when the family thought Clarice was possibly a prisoner of war. LIEUT. CLARICE ISOBEL HALLIGAN – VFX47776 EARLY LIFE IN MELBOURNE, AUSTRALIA Clarice Isobel Halligan was born in Ballarat, Victoria, in 1904, the third daughter of Joseph Patrick Halligan (22 yrs) and Emily Watson Chalmers (17yrs) who were married in Ballarat on 11th May, 1898. They had eight children altogether, 30/8/1899 Violet May (Chalmers), 2/7/1900 Minnie Margaret (Davenport), 17/9/1904 Clarice Isobel (Halligan), 12/9/1906 James Joseph Gordon, 9/3/1910 Jessie Chalmers (Piggott), 11/7/1913 John William, 1/11/1915 Winifred Elaine Emily (Rylah) and on 24/4/1918, Wallace Robert. She was the first of the siblings to die, on 16th February 1942, at the age of 37years. P a g e | 2 Joseph Patrick Halligan, started work at Ballarat Brewery and left to join Abbotsford Brewery, in Melbourne. The family at that time lived in a lovely Victorian House in the grounds of the Brewery in Abbotsford. Later on, they all moved to 167 Derby Street, Kew. (First photo in black and white) is of the house in a deteriorating situation after Clarice’s brother James Joseph Gordon (a bachelor) finally moved out in his older years. Second coloured photo is after it was sold and renovated. It still stands in 2017. Joseph rented stables in a back block, where a horse and jinker were kept for travel around Melbourne and for Joseph to get to work in East Melbourne.