My Father and the Capture of the Mata Hari in February 1942

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Intercultural Communication Competence Developed by Chinese in Communicating with Malays in Bangka Island, Indonesia∗

Sino-US English Teaching, April 2015, Vol. 12, No. 4, 299-309 doi:10.17265/1539-8072/2015.04.009 D DAVID PUBLISHING Intercultural Communication Competence Developed by Chinese in Communicating With Malays in Bangka Island, Indonesia∗ Deddy Mulyana Agustina Zubair Padjadjaran University, Bandung, Indonesia University of Mercu Buana, Jakarta, Indonesia This study aims to explore the cultural identity of Chinese related to their self-perception, their perception of Malays, and their communication with the Malays in Bangka Island, Indonesia, emphasizing the Chinese intercultural communication competence in terms of their self-presentation in business relationships with the Malays. The study employed an interpretive approach, more specifically the symbolic interactionist and dramaturgical tradition. The researchers focused on intercultural communication experiences and competence as enacted by the 25 Chinese in the area of the research. The study used in-depth interviews with the Chinese as the main method with some observation of the Chinese communication with the Malays. The researchers also interviewed eight Malays as additional subjects of the research to corroborate the research findings. The study found that the Chinese in Bangka Island perceived themselves as open and willing to mingle with the Malays. They are hospitable, hardworking, tenacious, frugal, and fond of maintaining long-term relationships. In contrast, in the Chinese view, the Malays are open and willing to mingle with others, obedient to the teachings of Islam, but they are lazy and are keen on being flattered, consumptive, and easily seduced. In terms of their intercultural communication competence, the Chinese are skillful in their self-presentation by employing various verbal and nonverbal tactics to adjust themselves to the interpersonal, group, and business situations where they encounter the Malays in their everyday lives. -

Issue125 – Jan 2016

CASCABEL Journal of the ROYAL AUSTRALIAN ARTILLERY ASSOCIATION (VICTORIA) INCORPORATED ABN 22 850 898 908 ISSUE 125 Published Quarterly in JANUARY 2016 Victoria Australia Russian 6 inch 35 Calibre naval gun 1877 Refer to the Suomenlinna article on #37 Article Pages Assn Contacts, Conditions & Copyright 3 The President Writes & Membership Report 5 From The Colonel Commandant + a message from the Battery Commander 6 From the Secretary’s Table 7 A message from the Battery Commander 2/10 Light Battery RAA 8 Letters to the Editor 11 Tradition Continues– St Barbara’s Day Parade 2015 (Cont. on page 51) 13 My trip to the Western Front. 14 Saint Barbara’s Day greeting 15 RAA Luncheon 17 Broome’s One Day War 18 First to fly new flag 24 Inspiring leadership 25 Victoria Cross awarded to Lance Corporal for Afghanistan rescue 26 CANADIAN tribute to the results of PTSD. + Monopoly 27 Skunk: A Weapon From Israel + Army Remembrance Pin 28 African pouched rats 29 Collections of engraved Zippo lighters 30 Flying sisters take flight 31 A variety of links for your enjoyment 32 New grenade launcher approved + VALE Luke Worsley 33 Defence of Darwin Experience won a 2014 Travellers' Choice Award: 35 Two Hundred and Fifty Years of H M S Victory 36 Suomenlinna Island Fortress 37 National Gunner Dinner on the 27th May 2017. 38 WHEN is a veteran not a war veteran? 39 Report: British Sniper Saves Boy, Father 40 14th Annual Vivian Bullwinkel Oration 41 Some other military reflections 42 Aussies under fire "like rain on water" in Afghan ambush 45 It’s something most of us never hear / think much about.. -

PROFIL PROVINSI KEPULAUAN BANGKA BELITUNG 2020.Pdf

PEMERINTAH PROVINSI KEPULAUAN BANGKA BELITUNG DINAS KOMUNIKASI DAN INFORMATIKA Scan QR CODE untuk mendownload PROVINSI KEPULAUAN BANGKA BELITUNG file buku versi pdf Layanan TASPEN CARE Memudahkan #SobatTaspen di mana saja dan kapan saja Ajukan Pertanyaan Download Formulir Klaim Jadwal Mobil Layanan TASPEN Kamus TASPEN 1 500 919 taspen.co.id TIM PENYUSUN Penulis Soraya B Larasati Editor Reza Ahmad Tim Penyusun Dr. Drs. Sudarman, MMSI Nades Triyani, S.Si, M.Si. Erik Pamu Singgih Nastoto, S.E. Sumber Data Dinas Komunikasi dan Informatika Provinsi Kepulauan Bangka Belitung Ide Kreatif Hisar Hendriko Berto Joshua Desain & Penata Grafis Otheng Sattar Penerbit PT Micepro Indonesia ISBN 978-623-93246-4-3 HAK CIPTA DILINDUNGI UNDANG UNDANG DITERBITKAN OLEH: Dilarang memperbanyak buku ini sebagian atau PT Micepro Indonesia seluruhnya, baik dalam bentuk foto copy, cetak, mikro Jl. Delima Raya No. 16, Buaran Jakarta Timur 13460 film,elektronik maupun bentuk lainnya, kecuali untuk Telp. 021- 2138 5185, 021-2138 5165 keperluan pendidikan atau non komesial lainnya dengan Fax: 021 - 2138 5165 mencantumkan sumbernya: Author/Editor: Dinas Email : [email protected] Komunikasi dan Informatika Provinsi Kepulauan Bangka Belitung dan Reza Ahmad, Buku: Profil Provinsi Kepulauan Bangka Belitung 2020; Penerbit: PT Micepro Indonesia TERAS REDAKSI Berbicara mengenai perjalanan Pemerintah Provinsi Talking about the journey of the Bangka Belitung Kepulauan Bangka Belitung di bawah kepemimpinan Islands Provincial Government under the leadership Erzaldi Rosman, maka kita akan berbicara mengenai of Erzaldi Rosman, then we will talk about various beragam pencapaian dan keberhasilan. Bukan hanya achievements and successes. Not only in the economic di sektor ekonomi dan wisata, beragam sektor lainnya and tourism sector, various other sectors cannot be juga tak bisa dipandang sebelah mata. -

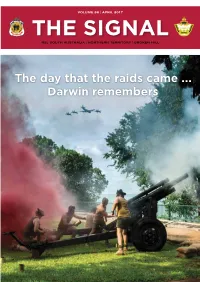

The Day That the Raids Came ... Darwin Remembers RSL CARE SA

VOLUME 86 | APRIL 2017 R E T E U U R G N A E E D L & SERVICES A F F I LI AT E RSL SOUTH AUSTRALIA | NORTHERN TERRITORY | BROKEN HILL The day that the raids came ... Darwin remembers RSL CARE SA RSL Care SA, providing a range of care and support services for the ex-service and veteran community. RSL Care SA has extensive experience and understanding of DVA and the implications of DVA entitlements entering residential aged care. For many people, considering nursing home aged care can be a stressful time. Our friendly admissions team is available to help guide you through the process and answer questions you may have. The Australian Government has strong protections in place to ensure that care is affordable for everyone and also subsidises a range of aged care services in Australia. Our nursing homes or residential aged care facilities offer short-term respite care or permanent care options. RSL Care SA has care facilities in Myrtle Bank and Angle Park. The War Veterans’ Home (WVH) is located in Myrtle Bank only 4kms from the CBD and is home to 95 residents. RSL Villas are situated next to Remembrance Park in Angle Park, 9kms north-west of the city. If you would like more information regarding residential aged care, the implications of DVA payments in aged care or to be considered for a place in one of our facilities, please call our admissions team on 08 8379 2600. For more information visit our website www.rslcaresa.com.au or www.myagedcare.gov.au War Veterans’ Home RSL Villas 55 Ferguson Avenue, Myrtle Bank SA 5064 18 Trafford Street, -

O. Smedal Affinity, Consanguinity, and Incest; the Case of the Orang Lom, Bangka, Indonesia

O. Smedal Affinity, consanguinity, and incest; The case of the orang Lom, Bangka, Indonesia In: Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde 147 (1991), no: 1, Leiden, 96-127 This PDF-file was downloaded from http://www.kitlv-journals.nl Downloaded from Brill.com09/25/2021 10:20:26PM via free access OLAF H. SMEDAL AFFINITY, CONSANGUINITY, AND INCEST: THE CASE OF THE ORANG LOM, BANGKA, INDONESIA The Lom, sometimes also referred to as the Mapur, are a Malay-speakingl group occupying an area of some 200 square kilometres in north-eastern Bangka - an island situated in the South China Sea, very roughly midway between Singapore and Jakarta (see Map l). Presently the Lom number some 800 individuals, most of whom live in nuclear family units. About fifty per cent of the population live in kampung Air Abik and the surround- ing forest - the other fifty per cent are found along the coast, many of them in kampung Pejam (see Map 2). The Lom grow hilllupland rice, cassava and yams in swiddens; cash crops such as pepper, cloves, pineapples and bananas (to name but a few); and coconuts along the sea shore. Most households keep some chickens and a dog andlor a cat. Those growing coconuts usually raise pigs, which they sell at the market in the nearest town (Belinyu) or to the inhabitants of some of the nearby villages, occu- pied primarily by ethnic Chinese. Published accounts of the Lom are scant and, as far as I know, have al1 been written by non-anthropologists. In the main they describe the ma- terial life of this 'heathen' population in the briefest of terms, stressing that the Lom eat indiscriminately and emphasizing their laziness and low 1 To say that they are Malay-speaking is to over-simplify. -

Traces of Sino-Moslem Malay Descendants from Johor in Mento-Bangka

International Seminar and Workshop on Urban Planning and Community Development IWUPCD 2017: 18th-22nd September 2017 ISBN: 978-602- 5428-06- 7| Pg. 117-128 Shared Urban Heritage: Traces of Sino-Moslem Malay Descendants from Johor in Mento-Bangka Kemas Ridwan Kurniawan1, Muhammad Naufal Fadhil2, Sutanrai Abdilah3 1, 2, 3Department of Architecture, Universitas Indonesia [email protected] ABSTRACT This paper aims to trace back the descendants of Liem Tau Kian (a former minister of Chinese Emperor who saught asylum in Johor State) who established the town of Mento in the early 18th century. Mento is the latest pre-European colonial city in Bangka before the island occupied by British and Dutch in the early 19th century. These descendants migrated to Bangka due to the marriage between Palembang Sultan with one of Lim Thau Kian’s grand daughter, and also due to the interest in tin mining exploration. The issue raising on this paper concerns about shared urban heritage as the evidence of traces of relationship of these descendants (representing Sino-Moslem Malay from Johor) with people from Bangka, Palembang, Bugis and also Arab. The method to response on the above issue is through observation on historical physical relics including old burial grounds and buildings scattered in old Mento. The findings tells multicultural paradigm of these shared heritage that were practiced through inter-ethnic marriages, transit, and migration around Malay Peninsula and the archipelago. © 2017 IWUPCD. All rights reserved. Keywords: identity, migration, multiculture 1. Introduction Mento was the capital town in the Bangka Island during the reign of Sultanate of Palembang (18th century) and the Dutch colonial (19th – early 20th century) that consisted of several ethnic groups: Malay, Arabian, Chinese and European. -

Trent Burnard Trent Burnard Lieutenant Colonel Commanding Officer 10Th/27Th Battalion, the Royal South Australia Regiment

Official Newsletter of the Royal South Australia Regiment Association Inc Editor - David Laing 0407 791 822 MARCH 2017 Inside this issue: Association BBQ Support for the Battalion Darwin - 75 Years Ago 2 About 4 weeks ago Rodney Beames received a mid week telephone call from the CO of 10/27 Bn RSAR requesting catering support for a Battalion Leadership Week- LETTERS 3 end at Keswick Barracks. “No problem!” said Beamsey, “When is it?” he asked, an- ticipating about a 10 day lead. “This weekend!” said the CO! CPL Davo’s page 4 How could Rod say anything but “How many are we feeding and what times are they dining?” How To Contact Us 5 Once that was worked out, Rod got on the phone to some members and got a reli- able, well oiled (in more ways than one) crew together, to provide sustenance for up The Radji Beach 6/7 Massacre 1942 to 30 Officers and Other Ranks attending the Leadership Exercise. The RSARA crew were present on both days to ensure the soldiers were well fed, ANZAC Day plan 8 and the fact that there was very little wastage showed how much the Diggers en- joyed the food. (See letter below.) One of our own from 9 the 10th Bn AIF Rod wishes to thank Nat Cooke, Mick Standing, Russ Durdin and Norm Rathmann, and of course Mrs Cheryl Beames who all made the support successful. Again! Members List 10 Purple & Blue Brothers 11 12 Letter of Appreciation Mr Rod Beames President Royal South Australia Regiment Association Inc Dear Rod LETTER OF APPRECIATION - SUPPORT TO 10/27 BN RSAR LEADERSHIP WEEKEND I would like to express my warmest thanks to you and your team for the support you provided to the Battalion Command Team with the provision of the lunchtime BBQ’s on our recent training weekend. -

Training, Ethos, Camaraderie and Endurance of World War Two Australian POW Nurses

Training, ethos, camaraderie and endurance of World War Two Australian POW nurses By Sarah Fulford 1 Contents Page Chapter 1: Introduction ..................................................................................... 3 Chapter 2: Historical framework ...................................................................... 13 Chapter 3: The Historical Context of Australian Nursing .................................. 32 Chapter 4: The Nurses at War – World War Two ............................................. 43 Chapter 5: Ethos .............................................................................................. 61 Chapter 6: Camaraderie ................................................................................... 83 Chapter 7: Resourcefulness ........................................................................... 113 Chapter 8: Conclusion .................................................................................... 141 Appendices: Appendix 1: AANS Pledge of Service .............................................................. 144 Appendix 2: Images of the Nurses in Malaya ................................................. 145 Appendix 3: Vyner Brooke Nurses ................................................................. 153 Appendix 4: Image of the Vyner Brooke and maps showing the movement of nurses during internment .............................................................................. 155 Appendix 5: Drawings by POWS during internment ...................................... 158 Appendix 6: “The -

MAPPING the POTENTIAL of the OLD CITY TOURISM (Study of the History, Region and Cultural Value of the Old City on Bangka Island)

P-ISSN 2622-8831 Berumpun Journal: An International Journal of Social, Politics and Humanities Vol. 2 No. 1 March 2019 MAPPING THE POTENTIAL OF THE OLD CITY TOURISM (Study of the History, Region and Cultural Value of the Old City on Bangka Island) Jamilah Chollilah [email protected] Herdiyanti [email protected] Nurvita Wijayanti [email protected] Novendra Hidayat [email protected] University of Bangka Belitung Pangkalpinang, Bangka Belitung Archipelago, Indonesia ABSTRACT This research is entitled Mapping the Tourism Potential of the Old City (Study of the History, Region and Cultural Value of the Old City on Bangka Island). The research objective was to map the tourism potential of the old city in Bangka Island, namely Belinyu and Muntok Districts. Overview this social mapping is divided into three aspects which include history, territory and cultural values. The problems in this study are formulated in three main questions, namely (1) How is the distribution of the old cities of Muntok and Belinyu based on Chinese, Malay and European clusters? (2) How does the distribution of the Chinese, Malay and European clusters affect the tourism promotion of the old city in Muntok and Belinyu? (3) How does Toponimi affect the tourism promotion of old cities in Muntok and Belinyu?The location of the study was conducted in Belinyu and Muntok Districts. The consideration is based on the search results of secondary data showing that these two regions were formerly known as the central areas of the Dutch colonial government (Muntok) and the center of tin mining activities (Belinyu).The research method used is descriptive qualitative research with social mapping techniques. -

The Story of 13

THE STORY OF 13th AUSTRALIAN GENERAL HOSPITAL 8th DIVISION 2nd A. I. F. 1941 – 1945 This un-official history of the 13 Australian General Hospital during WW2 was written by A.C. (Lex) Arthurson VX61276 who was a Corporal in the unit. It was prompted by former POW nurse Vivian Bullwinkel asking if the history had ever been written. Lex undertook to do it. With the assistance of others, it was completed over two years. The original document was enhanced by many newspaper cutting, pictures and sketches. It was not possible to reproduce these. Some alternative images have been inserted. (Most of the sketches inserted into the story were done by Corporal Dick Cochran 2/12 Field Company (Engineers) and provided to me by Ken Gray former National President ex POWs Association). I am grateful to Lex for permission to reproduce this history. It is pleasing to note the extensive (and rightful) coverage given to the Nurses in this history. Lt Col (Ret’d)Peter Winstanley OAM RFD (JP) May 2009 LIVES OF GREAT MEN ALL REMIND US WE CAN LIVE A LIFE SUBLIME AND, DEPARTING, LEAVE BEHIND US FOOTPRINTS IN THE SANDS OF TIME. QUATRAIN OF LONGFELLOW FROM “The Psalm of Life” Acknowledgements: Official Army Records Newspapers of 1945 - Melbourne Herald 1945 - Melbourne Age 1942 - Singapore Straits Times Special thanks to Mrs. Maureen Chandler for the loan of her father’s unique records of the 13th A.G.H. from 1941 – 1945. (Staff/Sgt. Pearce Wells was privy to all hospital records.) _________________________ Mrs Connie Cooper who loaned the diary of her husband, Staff/Sgt. -

Secrets & Spies Research Dossier

SECRETS & SPIES RESEARCH DOSSIER By ERSKINE PARK HIGH SCHOOL AUSTRALIA Andre Bernardino, Marc Graham, Umair Khan, Isaac Lim, Baylie Luke, Zack Lynch, Govind Mallath, Tyrone Myburgh-Sisam, Benjamin Tatlock, Lance Woodgate How Prisoners of War used secrecy to gain intelligence about the war, to communicate with the outside world and other camps, and to boost morale Introduction This report covers the ways Prisoners of War (POWs) used secrecy to gain intelligence about the war, to communicate with the outside world and to boost morale. The main focus point will be on Changi POW camp and the Thai Burma Railway, as this is the majority of experiences of ANZAC POWs in the Pacific. Changi was a harsh POW camp that held over 13,000 Australian POWs, and the majority of those were not treated well. The camp was unsanitary, there was a lack of food, a lack of doctors, and a severely large amount of death. They needed a way to send messages in an out of the camp so they could learn the news, but the camp did not allow conventional ways of communication to and from the camp. Therefore, they used strange ways to send secret messages from the camp. Our group, during this endeavor, also interviewed World War Two veteran David Trist. This interview gave us an insight in capturing Japanese POWs and how they were treated. He told us a story about himself, a guard, sharing a cigarette with a Japanese soldier, which we found really enlightening. 1 Impacts and experiences on Australian P.O.W Soldiers Over 22,000 Australian servicemen and almost forty nurses were captured by the Japanese. -

Indo 82 0 1161956077 97 1

Y a p T h ia m H ien a n d A c e h Daniel S. Lev Editor's Note: This article is actually the first chapter of a biography of Yap Thiam Hien which Daniel Tev had almost completed when he died on July 29, 2006. Arlene Lev has kindly given us permission to publish it here in her husband's memory, pending the eventual publication of the entire manuscript. We take this occasion to inform readers that the next issue of Indonesia will contain a special In Memoriam for Dan Lev, written by his friend Goenawan Mohamad. Yap Thiam Hien (1913-1989) was a lawyer and human rights activist. He was a founding member of the Badan Permusyawaratan Kewarga-Negaraan Indonesia (Baperki) and a major proponent of strengthening the rule of law in Indonesia. He defended the unpopular former foreign minister, Subandrio, in the Mahmillub [Military Tribunal-Extraordinary] trials in 1966 and was a firm advocate of the full legal equality of Chinese Indonesians. He was closely involved in the Legal Aid Institute (LBH, Lembaga Bantuan Hukum) and in nearly every major national project of legal reform or defense of human rights in Indonesia. He was the first recipient of the justice William ]. Brennan award for the defense of Human Rights. Ask just about anyone who knew Yap Thiam Hien and soon you will be told that what accounted for his character is that he was from Aceh. Indonesia's ethnic variety makes for this kind of easy, stereotypical generalization. Javanese are soft-spoken, subtle, manipulative, and sophisticated masters of compromise.