Ph.D. AC1.H3 5086 R.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The University of Chicago Tears in the Imperial Screen

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO TEARS IN THE IMPERIAL SCREEN: WARTIME COLONIAL KOREAN CINEMA, 1936-1945 A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE DIVISION OF THE HUMANITIES IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF EAST ASIAN LANGUAGES AND CIVILIZATIONS BY HYUN HEE PARK CHICAGO, ILLINOIS AUGUST 2017 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF TABLES ...…………………..………………………………...……… iii LIST OF FIGURES ...…………………………………………………..……….. iv ABSTRACT ...………………………….………………………………………. vi CHAPTER 1 ………………………..…..……………………………………..… 1 INTRODUCTION CHAPTER 2 ……………………………..…………………….……………..… 36 ENLIGHTENMENT AND DISENCHANTMENT: THE NEW WOMAN, COLONIAL POLICE, AND THE RISE OF NEW CITIZENSHIP IN SWEET DREAM (1936) CHAPTER 3 ……………………………...…………………………………..… 89 REJECTED SINCERITY: THE FALSE LOGIC OF BECOMING IMPERIAL CITIZENS IN THE VOLUNTEER FILMS CHAPTER 4 ………………………………………………………………… 137 ORPHANS AS METAPHOR: COLONIAL REALISM IN CH’OE IN-GYU’S CHILDREN TRILOGY CHAPTER 5 …………………………………………….…………………… 192 THE PLEASURE OF TEARS: CHOSŎN STRAIT (1943), WOMAN’S FILM, AND WARTIME SPECTATORSHIP CHAPTER 6 …………………………………………….…………………… 241 CONCLUSION BIBLIOGRAPHY …………………………………………………………….. 253 FILMOGRAPHY OF EXTANT COLONIAL KOREAN FILMS …………... 265 ii LIST OF TABLES Page Table 1. Newspaper articles regarding traffic film screening events ………....…54 Table 2. Newspaper articles regarding traffic film production ……………..….. 56 iii LIST OF FIGURES Page Figure. 1-1. DVDs of “The Past Unearthed” series ...……………..………..…..... 3 Figure. 1-2. News articles on “hygiene film screening” in Maeil sinbo ….…... 27 Figure. 2-1. An advertisement for Sweet Dream in Maeil sinbo……………… 42 Figure. 2-2. Stills from Sweet Dream ………………………………………… 59 Figure. 2-3. Stills from the beginning part of Sweet Dream ………………….…65 Figure. 2-4. Change of Ae-sun in Sweet Dream ……………………………… 76 Figure. 3-1. An advertisement of Volunteer ………………………………….. 99 Figure. 3-2. Stills from Volunteer …………………………………...……… 108 Figure. -

Yokohama Dance Collection EX 2015 Competition Winners Decided!

Yokohama Dance Collection EX 2015 Competition Winners Decided! Yokohama Dance Collection EX, which aims to nurture young choreographers, marks its 20th anniversary its main program, Competition I & Competition II were held from 5th February to 8th February at Yokohama Red Brick Warehouse No.1, and winners have been chosen. CompetitionⅠ 10 Finalists from 4 countries / 90 Entrants from 9 countries Prize Name of Winner / Work Age (as of 31th July, 2014) / Birthplace Jury Prize Mikiko KAWAMURA The French Embassy Prize 24 / Tokyo, Japan “Inner Mommy” for Young Choreographer (Supported by:Air France) Haruka KAJIMOTO MASDANZA Prize 31 / Ehime, Japan “then and after that” Sibiu International Ikumi KUROSU / Naoto KATORI Theater Festival Prize 26 / Saitama, Japan “RE:DIVISION” Touchpoint Art Foundation Prize Kaho KOGURE Encouragement Prize 24 / Saitama, Japan “Far Eriche” Ai TOHTOUMI Encouragement Prize 29 / Tokyo, Japan “Daytime soliloguy” Razel Ann Aguda MITCHAO Encouragement Prize 24 / Bacolod, Philippines “LA ELLE S’EN VA (there she goes)” 《Jury》 Shinji ONO (Producer, Aoyama Theatre/ Aoyama Round Theatre) Hiroko SHINDO (Dance Critics) Keizo MAEDA (Producer, Tokyo Metropolitan Theatre) Fumio HAMANO (Senior Editor, Shinshokan Dance Magazine) Ko MUROBUSHI (Dancer, Choreographer) Juliette de Charmony (Director, Institut français du Japon – Yokohama) Véronique Denis-Laroque (in charge of performing arts at Embassy of France/ Institut français du Japon) Yuval Pick (Director, Centre Chorégraphique National de Rillieux-la-Pape) 1 Competition Ⅱ(New -

The Front Page First Opened at the Times Square Theatre on August 14, 1928, It Was Instantly Heralded As a Classic

SUPPORT FOR THE 2019 SEASON OF THE FESTIVAL THEATRE IS GENEROUSLY PROVIDED BY DANIEL BERNSTEIN AND CLAIRE FOERSTER PRODUCTION SUPPORT IS GENEROUSLY PROVIDED BY NONA MACDONALD HEASLIP 2 DIRECTOR’S NOTES SCAVENGING FOR THE TRUTH BY GRAHAM ABBEY “Were it left to me to decide between a government without newspapers or newspapers without a government, I should not hesitate a moment to prefer the latter.” – Thomas Jefferson, 1787 When The Front Page first opened at the Times Square Theatre on August 14, 1928, it was instantly heralded as a classic. Nearly a century later, this iconic play has retained its place as one of the great American stage comedies of all time. Its lasting legacy stands as a testament to its unique DNA: part farce, part melodrama, with a healthy dose of romance thrown into the mix, The Front Page is at once a veneration and a reproof of the gritty, seductive world of Chicago journalism, firmly embedded in the freewheeling euphoria of the Roaring Twenties. According to playwrights (and former Chicago reporters) Charles MacArthur and Ben Hecht, the play allegedly found its genesis in two real-life events: a practical joke carried out on MacArthur as he was heading west on a train with his fiancée, and the escape and disappearance of the notorious gangster “Terrible” Tommy consuming the conflicted heart of a city O’Conner four days before his scheduled caught in the momentum of progress while execution at the Cook County Jail. celebrating the underdogs who were lost in its wake. O’Conner’s escape proved to be a seminal moment in the history of a city struggling Chicago’s metamorphosis through the to find its identity amidst the social, cultural “twisted twenties” is a paradox in and of and industrial renaissance of the 1920s. -

Western Literature in Japanese Film (1910-1938) Alex Pinar

ADVERTIMENT. Lʼaccés als continguts dʼaquesta tesi doctoral i la seva utilització ha de respectar els drets de la persona autora. Pot ser utilitzada per a consulta o estudi personal, així com en activitats o materials dʼinvestigació i docència en els termes establerts a lʼart. 32 del Text Refós de la Llei de Propietat Intel·lectual (RDL 1/1996). Per altres utilitzacions es requereix lʼautorització prèvia i expressa de la persona autora. En qualsevol cas, en la utilització dels seus continguts caldrà indicar de forma clara el nom i cognoms de la persona autora i el títol de la tesi doctoral. No sʼautoritza la seva reproducció o altres formes dʼexplotació efectuades amb finalitats de lucre ni la seva comunicació pública des dʼun lloc aliè al servei TDX. Tampoc sʼautoritza la presentació del seu contingut en una finestra o marc aliè a TDX (framing). Aquesta reserva de drets afecta tant als continguts de la tesi com als seus resums i índexs. ADVERTENCIA. El acceso a los contenidos de esta tesis doctoral y su utilización debe respetar los derechos de la persona autora. Puede ser utilizada para consulta o estudio personal, así como en actividades o materiales de investigación y docencia en los términos establecidos en el art. 32 del Texto Refundido de la Ley de Propiedad Intelectual (RDL 1/1996). Para otros usos se requiere la autorización previa y expresa de la persona autora. En cualquier caso, en la utilización de sus contenidos se deberá indicar de forma clara el nombre y apellidos de la persona autora y el título de la tesis doctoral. -

Murakami Goes to the Movies - from the Current - the Criterion Collection

5/27/2016 Gods and Monsters: Murakami Goes to the Movies - From the Current - The Criterion Collection What’s Happening on Hulu Timothy Brock on Restoring Charlie Chaplin’s Sound By Hillary Weston Repertory Pick: Mitchum in Minnesota The Inspiring Work of the Ghetto Film School The Screenplayer By Sam Wasson Gods and Monsters: Murakami Goes to the Movies By Glen Helfand https://www.criterion.com/current/posts/3827-gods-and-monsters-murakami-goes-to-the-movies 1/7 5/27/2016 Gods and Monsters: Murakami Goes to the Movies - From the Current - The Criterion Collection In contemporary art, the feature film is a pinnacle form. It offers abundant possibilities to tell stories, address themes in a nuanced, durational manner, create carefully art-directed universes, and reach audiences much larger and more diverse than those at any gallery or museum. So for Takashi Murakami, an artist known for his ambitious multimedia practice, international scope, and brand-name recognition, feature film was inevitable. Since the 1990s, his work has grown to encompass a staggering range of media—from large-scale painting and sculpture to Louis Vuitton bags—taking on the vast subject of the Japanese pop psyche on a global stage. It’s clear why an artist of Murakami’s stature would attempt the medium of film, but there was no guarantee that his gallery reputation would translate to success in cinema. The scale of a film requires a collaborative component—the cast and crew—that doesn’t jibe with the traditional idea of the artist alone in the studio creating a thoughtful masterpiece. -

A Comparison of the Verbal Teaching Patterns of Two Groups of Secondary

A comparison of the verbal teaching patterns of two groups of secondary student teachers, Montana State University, 1969-70 by Dennis Larry Martinen A thesis submitted to the Graduate Faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree \ of DOCTOR OF EDUCATION in Secondary Education Montana State University © Copyright by Dennis Larry Martinen (1970) Abstract: The problem in this study was to investigate the verbal teaching patterns of secondary student teachers and to determine essentially what these teaching patterns were. As a corollary to the problem, the Rokeach Dogmatism Scale and the Teaching Situation Reaction Test were administered to student teachers to determine if these tests could predict successful student teachers prior to their student teaching experience in the secondary schools of Montana. It was the purpose of this study, then, to record and analyze the verbal behavior patterns of two groups of secondary student teachers. One group, the control group, consisted of students who went through the regular training program. The other group received twenty hours of training in interaction analysis. Selected aspects of the reconstructed Flanders' matrix were compared and analyzed. Another aspect of the problem dealt with the possible predictive value of the Teaching Situation Reaction Test and the Rokeach Dogmatism Scale as they pertained to superior teaching. A comparison and analysis was made between scores achieved on the two tests and such quantitative elements as grade point average in the major subject area, mean scores on the rating forms used by Montana State University supervisors and the grade given to measure the success in student teaching. -

Black Bottom of Modernity: the Racial Imagination of Japanese Modernism in the 1930S

The Japanese Journal of American Studies, No. 27 (2016) Copyright © 2016 Keiko Nitta. All rights reserved. This work may be used, with this notice included, for noncommercial purposes. No copies of this work may be distributed, electronically or otherwise, in whole or in part, without permission from the author. Black Bottom of Modernity: The Racial Imagination of Japanese Modernism in the 1930s Keiko NITTA* APPROPRIATION OF THE PRIMITIVE In 1930, the eminent Japanese literary critic of the day Soichi Oya summarized “modernism” in terms of its fascination with the element of the “primitive”: Modernism starts with abolishing the traditional norms of various phases of life. Free and unrestricted from everything, and led by the most intense stimulus, it amplifies its own excitement; in this sense, modernism has much in common with primitivism. It is jazz that flows with colorful artificial illumination to the pavements of the modern metropolis, bewitching pedestrians. Such bewitching exemplifies the surrender of civilizations to barbarism.1 As Oya stated here, jazz was symbolized as something not merely primitive but also something indicating a modern taste for “barbarism.” Similar to the contemporaneous American author F. Scott Fitzgerald, who coined the term “the Jazz Age,”2 Japanese intellectuals attempted to establish their own “modernized” status as consumers of art and culture defined as primitive. It *Professor, Rikkyo University 97 98 KEIKO NITTA is to this paradoxical imagination of Japanese modernism that I turn my attention in this article. I will particularly look at creational tendencies of a short-lived but once quite dominant literary circle in Japan in the early 1930s. -

Interpreting Zheng Chenggong: the Politics of Dramatizing

, - 'I ., . UN1VERSIlY OF HAWAII UBRARY 3~31 INTERPRETING ZHENG CHENGGONG: THE POLITICS OF DRAMATIZING A HISTORICAL FIGURE IN JAPAN, CHINA, AND TAIWAN (1700-1963) A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAW AI'I IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN THEATRE AUGUST 2007 By Chong Wang Thesis Committee: Julie A. Iezzi, Chairperson Lurana D. O'Malley Elizabeth Wichmann-Walczak · - ii .' --, L-' ~ J HAWN CB5 \ .H3 \ no. YI,\ © Copyright 2007 By Chong Wang We certity that we have read this thesis and that, in our opinion, it is satisfactory in scope and quality as a thesis for the degree of Master of Arts in Theatre. TIIESIS COMMITTEE Chairperson iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I want to give my wannest thanks to my family for their strong support. I also want to give my since're thanks to Dr. Julie Iezzi for her careful guidance and tremendous patience during each stage of the writing process. Finally, I want to thank my proofreaders, Takenouchi Kaori and Vance McCoy, without whom this thesis could not have been completed. - . iv ABSTRACT Zheng Chenggong (1624 - 1662) was sired by Chinese merchant-pirate in Hirado, Nagasaki Prefecture, Japan. A general at the end of the Chinese Ming Dynasty, he was a prominent leader of the movement opposing the Manchu Qing Dynasty, and in recovering Taiwan from Dutch colonial occupation in 1661. Honored as a hero in Japan, China, and Taiwan, he has been dramatized in many plays in various theatre forms in Japan (since about 1700), China (since 1906), and Taiwan (since the 1920s). -

AY 2021 Spring Semester Courses Offered at Other Graduate Schools

AY 2021 Spring Semester Courses offered at other graduate schools Graduate School of Political Science spring semester Thur. 6 TheoriesonNewsReportingB SAWA,Yasuomi Japanese Semester Day/Period Course Title Instructor Language OKUYAMA, spring semester Mon. 2 Risk Management MURAYAMA, Japanese Toshihiro Takehiko SEGAWA, Shiro spring semester Mon. 3 FormalPoliticalTheoryI KURIZAKI,Shuhei Japanese/ spring semester Fri. 2 Political Propaganda KISHI, Toshimitsu Japanese English spring semester Fri. 3 Politics in East Asian Countries TANG, Liang Japanese spring semester Mon. 3 Qualitative Comparative Analysis HINO, Airo Japanese Fri. 4 NIIKAWA, Sho spring semester Introduction ofEconomicsfor Journalists TANAKA, Hidetomi Japanese Fri. 4 spring semester Mon. 3 Democratization JOU, Willy English spring semester Study of Visual Journalism TANIKAWA, Takeshi Japanese Fri. 5 spring semester Mon. 3 Journalism and Public Affairs SEGAWA, Shiro Japanese spring semester History of Modern Japanese Political Thought UMEMORI, Naoyuki English Fri. 5 spring semester Mon. 4 TheoryofGovernanceSystem KATAYAMA, Japanese spring semester Advertising UTADA, Akihiro Japanese Yoshihiro spring semester Fri. 5 ContemporaryJournalism[F] OTA,Masakatsu Japanese Mon. 4 spring semester Labour Economics FUKUSHIMA, Japanese spring semester Fri. 5 Bioethics FUJII, Tatsuo Japanese Yoshihiko Fri. 6 spring semester Mon. 5 Applied Theory of Fiscal and Financial System SHIMIZU, Osamu Japanese spring semester NPO/NGOTheory NODA,Masato Japanese Sat. 1 spring semester Mon. 6 International Political Economy SEDDON, Jack English spring semester IntellectualPropertyLaw KUWABARA,Shun Japanese spring semester Mon. 6 ContemporaryJournalism GREIMEL,KarlHans English spring semester Sat. 3 LocalAutonomyAdvancedCourse KATAYAMA, Japanese Yoshihiro Mon. 6 spring semester Public Policy in Perspectives of Economics FUKUSHIMA, Japanese spring semester Sat. 3-4 Health Policy(Tsubono) TSUBONO, Japanese Yoshihiko Yoshitaka Mon. -

A VERBAL SPACE – INTERSECTING the VISIBLE Virve Sarapik

A VERBAL SPACE – INTERSECTING THE VISIBLE Virve Sarapik The idea that man is not able to conceive of reality consciously is a very old one. An intermediate stage is necessary. Through this the real world may acquire the face of intermediary, relying on the sense-organs, experience, language, univer- sals, categorisation. Continuity of the outside world needs some points of sup- port. It is easier to comprehend discrete entities than a continuum and the best means for categorisation is language. Counterbalance to this much criticised lan- guage-centred viewpoint is idea of the importance of visual experience, phrased in the sentence attributed to Aristotle, "one picture is worth a thousand words." These two points of view on art clash in two ways: in the reciprocal condi- tionality of the pictorial and verbal expression, and in art as language. The two main issues concerning art and language can be formulated as: – the communicative quality of an artwork, i.e. the problem of the meaning of an artwork and art as language; – relations of the verbal language and artwork, or the influence of the verbal context on the meaning of an artwork. 1. Plato's paradox Once, reading Victor Burgin's book The End of Art Theory, I found a surprising passage. Debating the main opponent of the theory of postmodern art Clement Greenberg, Burgin writes: "In the Phaedo, Plato puts into the mouth of Socrates a doctrine of two worlds: the world of murky imperfection to which our mortal senses have access, and an "upper world" of perfection and light. Discursive speech is the tangled and inept medium to which we are condemned in the for- mer, while in the latter all things are communicated visually as a pure and un- mediated intelligibility which has no need for words." (Burgin 1986: 31.) A Verbal Space – Intersecting the Visible The idea, that there are two forms of communication: words and images (the second one being more direct), was passed to the Christian tradition with New Platonism. -

Downloads, and Weekly Attendees

riscilla apersVol 32, No 4 | Autumn 2018 PPThe academic journal of CBE International Social Sciences 3 Muted Group Theory: A Tool for Hearing Marginalized Voices Linda Lee Smith Barkman 8 The Importance of Age Norms When Considering Gender Issues Jason Eden and Naomi Eden 14 Christian Women’s Beliefs on Female Subordination and Male Authority Susan H. Howell and Kristyn Duncan 15 The Experiences of Women in Church and Denominational Leadership Susan H. Howell and Ariel Thompson 18 Marriage Ideology and Decision-Making Susan H. Howell, Bethany G. Lester, Alayna N. Owens 23 The Delight of Daughters: A Theology of Daughterhood Beulah Wood 29 Book Review: Biblical Porn: Affect, Labor, and Pastor Mark Driscoll’s Evangelical Empire by Jessica Johnson Jamin Hübner Priscilla and Aquila instructed Apollos more perfectly in the way of the Lord. (Acts 18:26) I Tertius . that made you fight to stay awake. It was the art (or lack thereof) of communication, which is a social science. Psychology and sociology, ethnography Consider counseling, a profession and skill set which and ethnology, political science and arises primarily from psychology. A Christian counselor economics. These and other social will approach psychology, and therefore counseling, with sciences are tools for understanding a certain set of theological beliefs. To give a final example, the people of the world—as individuals, Bible translation—surely an endeavor that underlies almost as families, as groups, as cultures and all biblical interpretation—happens at the intersection of subcultures. The articles in this issue of biblical studies and human language. And, of course, the Priscilla Papers all arise, directly or indirectly, from one or study of language (linguistics) and of the cultures that more social sciences. -

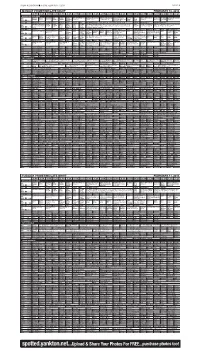

Spotted.Yankton.Net...Upload & Share Your Photos for FREE...Purchase

PRESS & DAKOTAN n FRIDAY, FEBRUARY 7, 2014 PAGE 9B MONDAY PRIMETIME/LATE NIGHT FEBRUARY 10, 2014 3:00 3:30 4:00 4:30 5:00 5:30 6:00 6:30 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 12:00 12:30 1:00 1:30 BROADCAST STATIONS Curious Arthur Å WordGirl Wild Martha Nightly PBS NewsHour (N) (In Antiques Roadshow Antiques Roadshow Independent Lens The Red BBC Charlie Rose (N) (In Tavis Smi- The Mind Antiques Roadshow PBS George (DVS) Å (DVS) Kratts Å Speaks Business Stereo) Å “Detroit” (N) Å “Eugene, OR” Å Mississippi agency and Green World Stereo) Å ley (N) Å of a Chef “Detroit” Å KUSD ^ 8 ^ Report civil rights. (N) Show News Å KTIV $ 4 $ XXII Olympics Ellen DeGeneres News 4 News News 4 Ent XXII Winter Olympics Alpine Skiing, Freestyle Skiing, Short Track. Å News 4 XXII Olympics XXII Winter Olympics XXII Winter Olympics Judge Judge KDLT NBC KDLT The Big XXII Winter Olympics Alpine Skiing, Freestyle Skiing, Short Track. From Sochi, KDLT XXII Winter Olympics XXII Winter Olympics Alpine Skiing, Freestyle NBC Speed Skating, Biath- Judy Å Judy Å News Nightly News Bang Russia. Alpine skiing: women’s super combined; freestyle skiing; short track. (N News Å Short Track, Luge. Å Skiing, Short Track. (In Stereo) Å KDLT % 5 % lon. Å (N) Å News (N) (N) Å Theory Same-day Tape) (In Stereo) Å KCAU ) 6 ) Dr. Phil Å The Dr. Oz Show News at ABC News Inside The Bachelor (N) (In Stereo) Å Castle “Valkyrie” News Jimmy Kimmel Live Nightline Paid Inside ABC World News Dr.