Observations on White-Browed Guan Penelope Jacucaca in North-East

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tinamiformes – Falconiformes

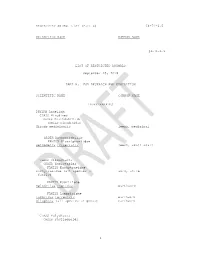

LIST OF THE 2,008 BIRD SPECIES (WITH SCIENTIFIC AND ENGLISH NAMES) KNOWN FROM THE A.O.U. CHECK-LIST AREA. Notes: "(A)" = accidental/casualin A.O.U. area; "(H)" -- recordedin A.O.U. area only from Hawaii; "(I)" = introducedinto A.O.U. area; "(N)" = has not bred in A.O.U. area but occursregularly as nonbreedingvisitor; "?" precedingname = extinct. TINAMIFORMES TINAMIDAE Tinamus major Great Tinamou. Nothocercusbonapartei Highland Tinamou. Crypturellus soui Little Tinamou. Crypturelluscinnamomeus Thicket Tinamou. Crypturellusboucardi Slaty-breastedTinamou. Crypturellus kerriae Choco Tinamou. GAVIIFORMES GAVIIDAE Gavia stellata Red-throated Loon. Gavia arctica Arctic Loon. Gavia pacifica Pacific Loon. Gavia immer Common Loon. Gavia adamsii Yellow-billed Loon. PODICIPEDIFORMES PODICIPEDIDAE Tachybaptusdominicus Least Grebe. Podilymbuspodiceps Pied-billed Grebe. ?Podilymbusgigas Atitlan Grebe. Podicepsauritus Horned Grebe. Podicepsgrisegena Red-neckedGrebe. Podicepsnigricollis Eared Grebe. Aechmophorusoccidentalis Western Grebe. Aechmophorusclarkii Clark's Grebe. PROCELLARIIFORMES DIOMEDEIDAE Thalassarchechlororhynchos Yellow-nosed Albatross. (A) Thalassarchecauta Shy Albatross.(A) Thalassarchemelanophris Black-browed Albatross. (A) Phoebetriapalpebrata Light-mantled Albatross. (A) Diomedea exulans WanderingAlbatross. (A) Phoebastriaimmutabilis Laysan Albatross. Phoebastrianigripes Black-lootedAlbatross. Phoebastriaalbatrus Short-tailedAlbatross. (N) PROCELLARIIDAE Fulmarus glacialis Northern Fulmar. Pterodroma neglecta KermadecPetrel. (A) Pterodroma -

Mexico Chiapas 15Th April to 27Th April 2021 (13 Days)

Mexico Chiapas 15th April to 27th April 2021 (13 days) Horned Guan by Adam Riley Chiapas is the southernmost state of Mexico, located on the border of Guatemala. Our 13 day tour of Chiapas takes in the very best of the areas birding sites such as San Cristobal de las Casas, Comitan, the Sumidero Canyon, Isthmus of Tehuantepec, Tapachula and Volcan Tacana. A myriad of beautiful and sought after species includes the amazing Giant Wren, localized Nava’s Wren, dainty Pink-headed Warbler, Rufous-collared Thrush, Garnet-throated and Amethyst-throated Hummingbird, Rufous-browed Wren, Blue-and-white Mockingbird, Bearded Screech Owl, Slender Sheartail, Belted Flycatcher, Red-breasted Chat, Bar-winged Oriole, Lesser Ground Cuckoo, Lesser Roadrunner, Cabanis’s Wren, Mayan Antthrush, Orange-breasted and Rose-bellied Bunting, West Mexican Chachalaca, Citreoline Trogon, Yellow-eyed Junco, Unspotted Saw-whet Owl and Long- tailed Sabrewing. Without doubt, the tour highlight is liable to be the incredible Horned Guan. While searching for this incomparable species, we can expect to come across a host of other highlights such as Emerald-chinned, Wine-throated and Azure-crowned Hummingbird, Cabanis’s Tanager and at night the haunting Fulvous Owl! RBL Mexico – Chiapas Itinerary 2 THE TOUR AT A GLANCE… THE ITINERARY Day 1 Arrival in Tuxtla Gutierrez, transfer to San Cristobal del las Casas Day 2 San Cristobal to Comitan Day 3 Comitan to Tuxtla Gutierrez Days 4, 5 & 6 Sumidero Canyon and Eastern Sierra tropical forests Day 7 Arriaga to Mapastepec via the Isthmus of Tehuantepec Day 8 Mapastepec to Tapachula Day 9 Benito Juarez el Plan to Chiquihuites Day 10 Chiquihuites to Volcan Tacana high camp & Horned Guan Day 11 Volcan Tacana high camp to Union Juarez Day 12 Union Juarez to Tapachula Day 13 Final departures from Tapachula TOUR MAP… RBL Mexico – Chiapas Itinerary 3 THE TOUR IN DETAIL… Day 1: Arrival in Tuxtla Gutierrez, transfer to San Cristobal del las Casas. -

Listing Five Foreign Bird Species in Colombia and Ecuador, South America, As Endangered Throughout Their Range; Final Rule

Vol. 78 Tuesday, No. 209 October 29, 2013 Part IV Department of the Interior Fish and Wildlife Service 50 CFR Part 17 Endangered and Threatened Wildlife and Plants; Listing Five Foreign Bird Species in Colombia and Ecuador, South America, as Endangered Throughout Their Range; Final Rule VerDate Mar<15>2010 18:44 Oct 28, 2013 Jkt 232001 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 4717 Sfmt 4717 E:\FR\FM\29OCR4.SGM 29OCR4 mstockstill on DSK4VPTVN1PROD with RULES4 64692 Federal Register / Vol. 78, No. 209 / Tuesday, October 29, 2013 / Rules and Regulations DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR endangered or threatened we are proposed for these five foreign bird required to publish in the Federal species as endangered, following careful Fish and Wildlife Service Register a proposed rule to list the consideration of all comments we species and, within 1 year of received during the public comment 50 CFR Part 17 publication of the proposed rule, a final periods. rule to add the species to the Lists of [Docket No. FWS–R9–IA–2009–12; III. Costs and Benefits 4500030115] Endangered and Threatened Wildlife and Plants. On July 7, 2009, we We have not analyzed the costs or RIN 1018–AV75 published a proposed rule in which we benefits of this rulemaking action determined that the blue-billed because the Act precludes consideration Endangered and Threatened Wildlife curassow, brown-banded antpitta, Cauca of such impacts on listing and delisting and Plants; Listing Five Foreign Bird guan, gorgeted wood-quail, and determinations. Instead, listing and Species in Colombia and Ecuador, Esmeraldas woodstar currently face delisting decisions are based solely on South America, as Endangered numerous threats and warrant listing the best scientific and commercial Throughout Their Range under the Act as endangered species (74 information available regarding the AGENCY: Fish and Wildlife Service, FR 32308). -

RESTRICTED ANIMAL LIST (Part A) §4-71-6.5 SCIENTIFIC NAME

RESTRICTED ANIMAL LIST (Part A) §4-71-6.5 SCIENTIFIC NAME COMMON NAME §4-71-6.5 LIST OF RESTRICTED ANIMALS September 25, 2018 PART A: FOR RESEARCH AND EXHIBITION SCIENTIFIC NAME COMMON NAME INVERTEBRATES PHYLUM Annelida CLASS Hirudinea ORDER Gnathobdellida FAMILY Hirudinidae Hirudo medicinalis leech, medicinal ORDER Rhynchobdellae FAMILY Glossiphoniidae Helobdella triserialis leech, small snail CLASS Oligochaeta ORDER Haplotaxida FAMILY Euchytraeidae Enchytraeidae (all species in worm, white family) FAMILY Eudrilidae Helodrilus foetidus earthworm FAMILY Lumbricidae Lumbricus terrestris earthworm Allophora (all species in genus) earthworm CLASS Polychaeta ORDER Phyllodocida 1 RESTRICTED ANIMAL LIST (Part A) §4-71-6.5 SCIENTIFIC NAME COMMON NAME FAMILY Nereidae Nereis japonica lugworm PHYLUM Arthropoda CLASS Arachnida ORDER Acari FAMILY Phytoseiidae Iphiseius degenerans predator, spider mite Mesoseiulus longipes predator, spider mite Mesoseiulus macropilis predator, spider mite Neoseiulus californicus predator, spider mite Neoseiulus longispinosus predator, spider mite Typhlodromus occidentalis mite, western predatory FAMILY Tetranychidae Tetranychus lintearius biocontrol agent, gorse CLASS Crustacea ORDER Amphipoda FAMILY Hyalidae Parhyale hawaiensis amphipod, marine ORDER Anomura FAMILY Porcellanidae Petrolisthes cabrolloi crab, porcelain Petrolisthes cinctipes crab, porcelain Petrolisthes elongatus crab, porcelain Petrolisthes eriomerus crab, porcelain Petrolisthes gracilis crab, porcelain Petrolisthes granulosus crab, porcelain Petrolisthes -

Alpha Codes for 2168 Bird Species (And 113 Non-Species Taxa) in Accordance with the 62Nd AOU Supplement (2021), Sorted Taxonomically

Four-letter (English Name) and Six-letter (Scientific Name) Alpha Codes for 2168 Bird Species (and 113 Non-Species Taxa) in accordance with the 62nd AOU Supplement (2021), sorted taxonomically Prepared by Peter Pyle and David F. DeSante The Institute for Bird Populations www.birdpop.org ENGLISH NAME 4-LETTER CODE SCIENTIFIC NAME 6-LETTER CODE Highland Tinamou HITI Nothocercus bonapartei NOTBON Great Tinamou GRTI Tinamus major TINMAJ Little Tinamou LITI Crypturellus soui CRYSOU Thicket Tinamou THTI Crypturellus cinnamomeus CRYCIN Slaty-breasted Tinamou SBTI Crypturellus boucardi CRYBOU Choco Tinamou CHTI Crypturellus kerriae CRYKER White-faced Whistling-Duck WFWD Dendrocygna viduata DENVID Black-bellied Whistling-Duck BBWD Dendrocygna autumnalis DENAUT West Indian Whistling-Duck WIWD Dendrocygna arborea DENARB Fulvous Whistling-Duck FUWD Dendrocygna bicolor DENBIC Emperor Goose EMGO Anser canagicus ANSCAN Snow Goose SNGO Anser caerulescens ANSCAE + Lesser Snow Goose White-morph LSGW Anser caerulescens caerulescens ANSCCA + Lesser Snow Goose Intermediate-morph LSGI Anser caerulescens caerulescens ANSCCA + Lesser Snow Goose Blue-morph LSGB Anser caerulescens caerulescens ANSCCA + Greater Snow Goose White-morph GSGW Anser caerulescens atlantica ANSCAT + Greater Snow Goose Intermediate-morph GSGI Anser caerulescens atlantica ANSCAT + Greater Snow Goose Blue-morph GSGB Anser caerulescens atlantica ANSCAT + Snow X Ross's Goose Hybrid SRGH Anser caerulescens x rossii ANSCAR + Snow/Ross's Goose SRGO Anser caerulescens/rossii ANSCRO Ross's Goose -

SWFSC Archive

CONTENTS LIST OF TABLES ........................................................................................................................ ii LIST OF FIGURES ...................................................................................................................... ii INTRODUCTION......................................................................................................................... 1 OBJECTIVES ............................................................................................................................... 1 STUDY AREA AND ITINERARY ............................................................................................. 2 MATERIALS AND METHODS ................................................................................................. 3 Oceanography ............................................................................................................................. 3 Net Tows ...................................................................................................................................... 4 Acoustic Backscatter.................................................................................................................... 4 Seabirds ....................................................................................................................................... 5 Contour Plots............................................................................................................................... 5 RESULTS ..................................................................................................................................... -

Recovery of the Trinidad Piping-Guan ( Pipile Pipile )

Expedition ID: 300605 Grant Category : Gold Grant Amount: $14,500 Project Pawi: Recovery of the Trinidad Piping-Guan ( Pipile pipile ) Team members: Jahson Alemu, Emma Davis, Aidan Keane, Kevin Mahabir, Srishti Mohais, Alesha Naranjit, Kerrie Naranjit, Bethany Stoker Contact: Aidan Keane Imperial College London Silwood Park Buckhurst Road Ascot Berks SL5 7PY [email protected] Acknowledgements The team would like to thank British Petroleum (BP), BirdLife International, Fauna and Flora International (FFI), Conservation International, Wildlife Conservation Society for funding the project. Special thanks go to Phil McGowan at the World Pheasant Association and to Marianne, Robyn and Kate at the BP Conservation Programme whose help and patience have been invaluable throughout. Project Pawi was only possible because of the generosity, support and encouragement of a large number of people within Trinidad itself, to whom we are very grateful. The team would particularly like to thank the members of the Pawi Study Group, tirelessly led by John and Margaret Cooper, for their practical help, thoughtful discussions and friendship. On ecological matters the guidance and expertise of Adrian Hailey and Howard Nelson was greatly appreciated. Grande Riviere has been at the heart of efforts to study the Pawi for many years, and once again played a central role in our project. We are indebted to owners of the Grande Riviere house for their generosity in allowing us to use the site as our base. The team would especially like to thank the guides of the Grande Riviere Nature Tour Guide Association and Mr Guy for their help and friendship. We are very grateful for the practical support provided by the University of the West Indies, Asa Wright, the Forestry Department, the Wildlife Section and the National Parks Section. -

Ecuador Birding the Chocó-Andes Region: Western and Eastern Slopes of Ecuador November 25-December 4, 2018

MINDO CLOUD FOREST ECUADOR Birding the Chocó-Andes Region: Western and Eastern Slopes of Ecuador NOVEMBER 25-DECEMBER 4, 2018 Per square mile, Ecuador has the PROGRAM HIGHLIGHTS highest biodiversity in the world, including some 1,640 species of birds, • Explore diverse habitats at varying elevations at national and private reserves, including Alambi Cloud Forest Reserve, many of which are rare and endemic. the subtropical rainforest at Milpe Bird Sanctuary, páramo Discover the amazing contrasts of ecosystem at Antisana Ecological Reserve, and more. cloud forest, the Amazon, and Andean landscapes on this 10-day birding • Seek out some of Ecuador’s approximately 130 adventure. With assistance from an hummingbird species, including the Giant Hummingbird, Black-tailed Trainbearer, Sword-billed Hummingbird, expert guide, encounter a variety of Tourmaline Sunangel, and Glowing Puffleg. birds, plants, and other wildlife while traversing a selection of Ecuador’s • Identify other target species like the Andean Condor, 50 different ecosystems. The program Andean Cock-of-the-rock, Long-wattled Umbrellabird, Chocó Trogon, and dozens of tanagers. begins with a journey to Mindo Loma Private Reserve and its 17 acres of primary and secondary recovering cloud forest. Also experience the WHAt’s INCLUDED? Milpe Bird Sanctuary in the Chocó • Bilingual local guide Andean foothills, considered one of • Driver the finest sites in all of Ecuador. Along • Accommodations the way, meet a famous Ecuadorian • Activities ornithologist, view the snow-capped • Private transportation Antisana Volcano, and straddle the • Meals equator at the Middle of the World • Beverages with meals Monument. • Carbon offsetting BUFF-TAILED CORONET BY JULIAN LONDONO holbrooktravel.com | 800-451-7111 ANTISANA VOLCANO BY MARCIO RAMALHO ITINERARY areas of original cloud forest habitat and wildlife, where you will be able to experience the natural beauty and BLD = BREAKFAST, LUNCH, DINNER wonder of this very unique and biologically diverse environment. -

The Cracidae – Chachalacas, Guans and Curassows the Cracidae Or

The Cracidae – Chachalacas, Guans and Curassows The Cracidae or cracids are a bird family group of ancient origin going back perhaps some 50 million years and currently inhabiting parts of South and Central America. The Craci are a sub-order of the Galliformes which also contains most of the best known game birds in the sub-order the Phasiani such as pheasants, grouse, guinea fowls, and quails. The other members of the Craci comprise the megapodes of Australasia. Cracids are mostly arboreal (tree-dwelling) species which typically inhabit forest environments and thus their biology and habits are not well known. There is a good deal of debate on how many species the family comprise but there are some 40 – 50 currently extant. Curassows are the largest in size of the birds in this group with measurements generally in the 70-80 cm range; Guans are slightly smaller (+/- 60cm) and Chachalacas the smallest in the group at +/- 50 cm. Chachalacas are all rather similar in appearance Plain Chachalaca Ortalis vetula Chaco Chachalaca Ortalis canicollis Cracids appear to be monogamous and make a rather flat rudimentary nest of sticks with two to four plain white or cream eggs being laid depending on the species; the eggs are quite large relative to the size of the bird although the nests tend to be relatively small. Little Chachalaca Ortalis motmot Rufous-vented Chachalaca Ortalis ruficauda All cracids are typically vegetarian eating fruits, seeds, flowers, buds and leaves but limited evidence shows that some animal matter, especially insects such as grasshoppers are taken. Most cracids are highly vocal and their calls can carry a considerable distance. -

Paleoceanographic Changes in the Late Pliocene Promoted Rapid

Paleoceanographic changes in the late Pliocene promoted rapid diversification in pelagic seabirds Joan Ferrer Obiol1, Helen James2, R. Chesser2, Vincent Bretagnolle3, Jacob Gonzales-Solis1, Julio Rozas1, Andreanna Welch4, and Marta Riutort1 1Universitat de Barcelona Facultat de Biologia 2Smithsonian Institution 3Centre d’Etudes´ Biologiques de Chiz´e,CNRS & La Rochelle Universit´e 4Durham University Department of Biosciences October 12, 2020 Abstract In marine environments, paleoceanographic changes can act as drivers of diversification and speciation, even in highly mobile marine organisms. Shearwaters are a group of pelagic seabirds with a well-resolved phylogeny that are globally distributed and show periods of both slow and rapid diversification. Using reduced representation sequencing data, we explored the role of paleoceanographic changes on diversification and speciation in these highly mobile pelagic seabirds. We performed molecular dating, applying a multispecies coalescent approach (MSC) to account for the high levels of incomplete lineage sorting (ILS). We identified a major effect of the Pliocene marine megafauna extinction, followed by a period of high dispersal and rapid speciation. Biogeographic analyses showed that dispersal appears to be favoured by surface ocean currents, and we found that founder and vicariant events are the main processes of diversification. Body mass appears to be a key phenotypic trait potentially under selection during shearwater diversification, and it shows significant associations with life strategies and local conditions. We also found incongruences between the current taxonomy and patterns of genomic divergence, suggesting revisions to alpha taxonomy. Globally, our findings extend our understanding on the drivers of speciation and dispersal of highly mobile pelagic seabirds and shed new light on the important role of paleoceanographic events. -

In Brazil, There Are Seven Species of the Genus Penelope (Cracidae: Galliformes)

ISSN 1981-1268 COSTA & CHRISTOFFERSEN (2016) 173 http://dx.doi.org/10.21707/gs.v10.n04a14 COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS OF VOCALIZATIONS OF GUANS (GALLIFORMES, CRACIDAE, PENELOPE) FROM BRAZIL (SOUTH AMERICA) DIMITRI DE ARAUJO COSTA1 & MARTIN LINDSEY CHRISTOFFERSEN1 1 Universidade Federal da Paraíba. Centro de Ciências Exatas e da Natureza. Departamento de Sistemática e Ecologia. João Pessoa, Paraíba, Brasil. Recebido em 23 de setembro de 2015. Aceito em 11 de julho de 2016. Publicado em 30 de setembro de 2016. ABSTRACT – The genus Penelope is a group of guans of the family Cracidae, Order Galliformes, which is widely distributed in Brazil, totaling seven species (Penelope jacquacu, P. jacucaca, P. marail, P. pileata, P. obscura, P. ochrogaster and P. superciliaris). Each guan species has a particular distribution, with the exception of the Rusty-margined Guan (P. superciliaris) that is found in almost all the national territory. The objective of this study involves analyzing the songs of the species of Penelope in different regions of Brazil, and comparing them to those of the species P. superciliaris to know if their singing patterns are modified when overlapping with other species of the genus, thus avoiding competition by acoustic interference. This comparative analysis involving several guan species is the first performed in cracids in the world, thus being highly relevant for future studies. Furthermore, we are providing the diagnostic characteristics, conservation status and ecological data of each species of the genus Penelope reported from Brazil. KEY WORDS: ACOUSTIC INTERFERENCE; APOMORPHIES; COMPETITION; CONSERVATION STATUS; CRACIDS. ANÁLISE COMPARATIVA DAS VOCALIZAÇÕES DOS JACUS (GALLIFORMES, CRACIDAE, PENELOPE) DO BRASIL (AMÉRICA DO SUL) RESUMO – O gênero Penelope é um grupo de jacus da família Cracidae, Ordem Galliformes, que é amplamente distribuído no Brasil, totalizando sete espécies (Penelope jacquacu, P. -

When China Rules the World

When China Rules the World 803P_pre.indd i 5/5/09 16:50:52 803P_pre.indd ii 5/5/09 16:50:52 martin jacques When China Rules the World The Rise of the Middle Kingdom and the End of the Western World ALLEN LANE an imprint of penguin books 803P_pre.indd iii 5/5/09 16:50:52 ALLEN LANE Published by the Penguin Group Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London wc2r orl, England Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, USA Penguin Group (Canada), 90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700, Toronto, Ontario, Canada m4p 2y3 (a division of Pearson Canada Inc.) Penguin Ireland, 25 St Stephen’s Green, Dublin 2, Ireland (a division of Penguin Books Ltd) Penguin Group (Australia), 250 Camberwell Road, Camberwell, Victoria 3124, Australia (a division of Pearson Australia Group Pty Ltd) Penguin Books India Pvt Ltd, 11 Community Centre, Panchsheel Park, New Delhi – 110 017, India Penguin Group (NZ), 67 Apollo Drive, North Shore 0632, New Zealand (a division of Pearson New Zealand Ltd) Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd, 24 Sturdee Avenue, Rosebank 2196, South Africa Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offi ces: 80 Strand, London wc2r orl, England www.penguin.com First published 2009 1 Copyright © Martin Jacques, 2009 The moral right of the author has been asserted All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book Typeset in 10.5/14pt Sabon by Palimpsest Book Production Limited, Grangemouth, Stirlingshire Printed in England by XXX ISBN: 978–0–713–99254–0 www.greenpenguin.co.uk Penguin Books is committed to a sustainable future for our business, our readers and our planet.