The Literary Structure of the Song of Songs Redivivus

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Church Holy Books 1. Holy Bible: Old Testament

Church Holy Books •How many books does the Church use? •What are they for and when are they used? 1. Holy Bible: Old Testament 39 Books: Books of the LAW (5): – Genesis – Exodus – Leviticus – Numbers – Deuteronomy 1 1. Holy Bible: Old Testament Historical Books (12): – Joshua – Judges – Ruth – 1 & 2 Samuel – 1 & 2 Kings – 1 & 2 Chronicles – Ezra – Nehemiah – Esther 1. Holy Bible: Old Testament Poetic Books (5): – Job – Psalms – Proverbs – Ecclesiastes – Song of Songs 2 1. Holy Bible: Old Testament Major Prophets (5): – Isaiah – Jeremiah – Lamentations of Jeremiah – Ezekiel – Daniel 1. Holy Bible: Old Testament Minor Prophets (12): Hosea Nahum Joel Habakkuk Amos Zephaniah Obadiah Haggai Jonah Zechariah Micah Malachi 3 1. Holy Bible “All Scripture is given by inspiration of God, and is profitable for doctrine, for reproof, for correction, for instruction in righteousness” (2 Timothy 3:16) Most important of all books All the other books are based upon It and inspired by It Our Church is an entirely Biblical Church relying on God’s inspired Word for our spiritual nourishment 1. Holy Bible: Old Testament Easy way to remember: – 5 – 12 – 5 – 5 – 12 – Law (5) – Historical (12) – Poetic (5) – Major Prophets (5) – Minor Prophets (12) 4 1. Holy Bible: Old Testament More Old Testament Books Deuterocanonical Books 10 additional books or parts of books were removed from the Protestant translation of the Bible, but exist in the Hebrew, Septuagint (Greek) and Vulgate (Latin) 1. Holy Bible: Old Testament According to the Coptic tradition, they are: – Tobit – Judith – 1 and 2 Maccabees – Wisdom – Sirach – Baruch – Rest of Esther – Additions to Daniel – Psalm 151 5 1. -

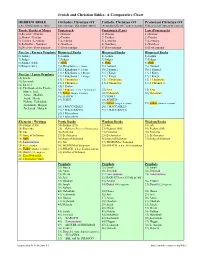

Hebrew and Christian Bibles: a Comparative Chart

Jewish and Christian Bibles: A Comparative Chart HEBREW BIBLE Orthodox Christian OT Catholic Christian OT Protestant Christian OT (a.k.a. TaNaK/Tanakh or Mikra) (based on longer LXX; various editions) (Alexandrian LXX, with 7 deutero-can. bks) (Cath. order, but 7 Apocrypha removed) Torah / Books of Moses Pentateuch Pentateuch (Law) Law (Pentateuch) 1) Bereshit / Genesis 1) Genesis 1) Genesis 1) Genesis 2) Shemot / Exodus 2) Exodus 2) Exodus 2) Exodus 3) VaYikra / Leviticus 3) Leviticus 3) Leviticus 3) Leviticus 4) BaMidbar / Numbers 4) Numbers 4) Numbers 4) Numbers 5) Devarim / Deuteronomy 5) Deuteronomy 5) Deuteronomy 5) Deuteronomy Nevi’im / Former Prophets Historical Books Historical Books Historical Books 6) Joshua 6) Joshua 6) Joshua 6) Joshua 7) Judges 7) Judges 7) Judges 7) Judges 8) Samuel (1&2) 8) Ruth 8) Ruth 8) Ruth 9) Kings (1&2) 9) 1 Kingdoms (= 1 Sam) 9) 1 Samuel 9) 1 Samuel 10) 2 Kingdoms (= 2 Sam) 10) 2 Samuel 10) 2 Samuel 11) 3 Kingdoms (= 1 Kings) 11) 1 Kings 11) 1 Kings Nevi’im / Latter Prophets 12) 4 Kingdoms (= 2 Kings) 12) 2 Kings 12) 2 Kings 10) Isaiah 13) 1 Chronicles 13) 1 Chronicles 13) 1 Chronicles 11) Jeremiah 14) 2 Chronicles 14) 2 Chronicles 14) 2 Chronicles 12) Ezekiel 15) 1 Esdras 13) The Book of the Twelve: 16) 2 Esdras (= Ezra + Nehemiah) 15) Ezra 15) Ezra Hosea, Joel, 17) Esther (longer version) 16) Nehemiah 16) Nehemiah Amos, Obadiah, 18) JUDITH 17) TOBIT Jonah, Micah, 19) TOBIT 18) JUDITH Nahum, Habakkuk, 19) Esther (longer version) 17) Esther (shorter version) Zephaniah, Haggai, 20) 1 MACCABEES 20) -

Guide to Reading Nevi'im and Ketuvim" Serves a Dual Purpose: (1) It Gives You an Overall Picture, a Sort of Textual Snapshot, of the Book You Are Reading

A Guide to Reading Nevi’im and Ketuvim By Seth (Avi) Kadish Contents (All materials are in Hebrew only unless otherwise noted.) Midrash Introduction (English) How to Use the Guide Sheets (English) Month 1: Yehoshua & Shofetim (1 page each) Month 2: Shemuel Month 3: Melakhim Month 4: Yeshayahu Month 5: Yirmiyahu (2 pages) Month 6: Yehezkel Month 7: Trei Asar (2 pages) Month 8: Iyyov Month 9: Mishlei & Kohelet Month 10: Megillot (except Kohelet) & Daniel Months 11-12: Divrei HaYamim & Ezra-Nehemiah (3 pages) Chart for Reading Sefer Tehillim (six-month cycle) Chart for Reading Sefer Tehillim (leap year) Guide to Reading the Five Megillot in the Synagogue Sources and Notes (English) A Guide to Reading Nevi’im and Ketuvim Introduction What purpose did the divisions serve? They let Moses pause to reflect between sections and between topics. The matter may be inferred: If a person who heard the Torah directly from the Holy One, Blessed be He, who spoke with the Holy Spirit, must pause to reflect between sections and between topics, then this is true all the more so for an ordinary person who hears it from another ordinary person. (On the parashiyot petuhot and setumot. From Dibbura de-Nedava at the beginning of Sifra.) A Basic Problem with Reading Tanakh Knowing where to stop to pause and reflect is not a trivial detail when it comes to reading Tanakh. In my own study, simply not knowing where to start reading and where to stop kept me, for many years, from picking up a Tanakh and reading the books I was unfamiliar with. -

Old Testament Basics LESSON 08 of 10 Old Testament Poetry

OT128 Old Testament Basics LESSON 08 of 10 Old Testament Poetry Dr. Sid Buzzell Experience: Dean of Christian University GlobalNet Introduction In this lesson, we study some of the Bible’s most profound and treasured literature. In fact it’s some of the most beautiful literature written anywhere. In this lesson, we will study Israel’s Old Testament poetry. There are five Old Testament books—Job, Psalms, Proverbs, the Song of Solomon, and Lamentations— that are written entirely or almost entirely in poetic form. Many narrative books contain poetry and so do all but two of the prophetic books. Isaiah contains some of the most magnificent poetry in all of the Old Testament. From Genesis to Malachi, the Old Testament is enriched by poetry. Characteristics of Old Testament Poetry Poetry is distilled language. While prose is usually explicit in its form, poetry is written in such a way that the reader has to interact with the writer. The message is written so the reader has to discover it by working with the poem’s construction. When writing in distilled language, the poet works very hard to find just the right word to make the poem work. He or she has to make the lines in the poetic verses interact with each other. The poet writes with the expectation that the reader work the meaning out of the poem and that truth discovered is more powerful than truth given. So if you try to read Old Testament poetry quickly, casually, easily, it won’t work. You have to get into the process. -

Parallelism in Hebrew Poetry Demonstrates a Major Error in the Hermeneutic of Many Old-Earth Creationists

Answers Research Journal 5 (2012):115–123. www.answersingenesis.org/arj/v5/parallelism-hebrew-poetry-old-earth.pdf Parallelism in Hebrew Poetry Demonstrates a Major Error in the Hermeneutic of Many Old-Earth Creationists Tim Chaffey, Web writer and editor, Answers in Genesis, Petersburg, Kentucky Abstract Many old-earth creationists cite poetic passages in an effort to convince people that we cannot and should not interpret the creation account literally. Yet the old-earth creationist is quick to interpret SRHWLFSDVVDJHVO LWHUDO O\DQGWUHDWWKHQD U UDWLYHSDVVDJHVÀJX UDWLYHO\7KLVD U WLFOHZ L O OSURYLGHDVX U YH\RI the nature of Hebrew poetry and provide examples of the various forms of parallelism exhibited in the six poetic books of the Bible: Job, Psalms, Proverbs, Ecclesiastes, Song of Solomon, and Lamentations. 7KHÀQDOVHFWLRQRIWKLVVWXG\ZLOOVKRZWKDW*HQHVLVLVQRWSRHWU\DQGDEULHIH[DPLQDWLRQRID SRSXODU2OG7HVWDPHQWHYHQWZLOOUHDGLO\GLVSOD\WKHYDVWGLIIHUHQFHVEHWZHHQQDUUDWLYHDQGSRHWU\ Keywords: narrative, Hebrew poetry, synonymous parallelism, antithetic parallelism, synthetic parallelism, framework hypothesis, progressive creationism, hermeneutics, old-earth creationism, chiasm Introduction 7KHVHFRQGW\SHRISDUDOOHOLVPLGHQWLÀHGE\/RZWK Poetry is a highly stylized form of writing used LVNQRZQDVDQWLWKHWLFSDUDOOHOLVPZKLFKLVQHDUO\WKH by many cultures, each having their own unique opposite of synonymous parallelism. This occurs when methods of conveying information. Americans and WKHVHFRQGVWLFKLVGLUHFWO\FRQWUDVWHGWRWKHÀUVWDQG other Westerners are familiar -

Pardes (Jewish Exegesis)

PaRDeS (Jewish exegesis) Pardes refers to (types of) approaches to biblical exegesis in rabbinic Judaism (or - simpler - interpretation of text in Torah study). The term, sometimes also spelled PaRDeS, is an acronym formed from the name initials of the following four approaches: .plain" ("simple") or the direct meaning" — (פְּשָׁ ט) Peshat • hints" or the deep (allegoric: hidden or" — (רֶ מֶ ז) Remez symbolic) meaning beyond just the literal sense. — ("from Hebrew darash: "inquire" ("seek — (דְּרַ ש) Derash • the comparative (midrashic) meaning, as given through similar occurrences. "pronounced with a long O as in 'bone') — "secret) (סֹוד) Sod • ("mystery") or the esoteric/mystical meaning, as given through inspiration or revelation. Tanakh ;[pronounced [taˈnaχ] or [təˈnax ,תַּ נַּ"ְך :The Tanakh (Hebrew also Tenakh, Tenak, Tanach) is the canon of the Hebrew Bible. The name Tanakh is an acronym of the first Hebrew letter of each of the Masoretic Text's three traditional subdivisions: Torah ("Teaching", also known as the Five Books of Moses), Nevi'im ("Prophets") and Ketuvim ("Writings")—hence meaning "that which is ,(מקרא) "TaNaKh. The name "Miqra read", is another Hebrew word for the Tanakh. The books of the Tanakh were passed on by each generation with the accompanying oral tradition, called the Oral Torah. also known as the Masoretic Text or Miqra. Torah Instruction", "Teaching") is a" ,ּתֹורָ ה :Torah (/ˈtɔːrə/; Hebrew central concept in the Jewish tradition. It has a range of meanings: it can most specifically mean the first five books of the Tanakh, it can mean this plus the rabbinic commentaries on it, it can mean the continued narrative from Genesis to the end of the Tanakh, it can even mean the totality of Jewish teaching and practice.[1] Common to all these meanings, Torah consists of the foundational narrative of the Jewish people: their call into being by God, their trials and tribulations, and their covenant with their God, which involves following a way of life embodied in a set of religious obligations and civil laws (halakha). -

A. the Tanak As the Foundation of Judaism

A. THE TANAK AS THE FOUNDATION OF JUDAISM THE TANAK, OR THE JEWISH BIBLE, stands as the quintessential foundation for Jewish life, identity, practice, and thought from antiquity through contemporary times. The five books of the Torah, or the Instruction of G-d to the Jewish people and the world at large, constitute the foundation of the Tanak. According to Jewish tradition (Exod 19—Num 10), the Torah was revealed to the nation Israel at Mount Sinai while the people were journeying from Egypt through the wilderness of Sinai on their way to return to the land of Israel to take up residence in the land promised by G-d to their ancestors, Abraham and Sarah; Isaac and Rebecca; Jacob, Rachel and Leah; and the twelve sons of Jacob. The four books of the Nevi’im Rishonim, or the Former Prophets, provide an account of Israel’s life in the land from the time of the conquest under Joshua until the time of the Babylonian exile, when Jerusalem and the Temple were destroyed and Jews were exiled to Babylonia and elsewhere in the world. The four books of the Nevi’im Ahronim, or the Latter Prophets, provide an assessment of the reasons why G-d chose to exile Jews from the land of Israel and the scenarios by which G-d would choose to restore Jews to the land of Israel once the exile was completed. The eleven books of the Ketuvim, or the Writings, include a variety of books of different form and purpose that address various aspects of Jewish worship, critical thought, future expectations, history, and life in the world, both in the land of Israel and beyond. -

Studies in Biblical Poetry the Collected Notes of C.A

Studies in Biblical Poetry The Collected Notes of C.A. LaRue 1 Table of Contents INTRODUCTION SECTION ONE: PSALMS SECTION TWO: LAMENTATIONS SECTION THREE: SONG OF SONGS SECTION FOUR: JOB SECTION FIVE: PROVERBS SECTION SIX: ECCLESIATES SECTION SEVEN: THE PROPHETS AND OTHER WRITINGS SECTION EIGHT: THE NEW TESTAMENT 2 INTRODUCTION: *from myjewishlearning.com The Poetic Writings Approximately one-third of the Old testament is written in poetry. The three main divisions-- the Law, the Prophets, and the Writings - contain poetry in successively greater amounts. Only seven Old Testament books - Leviticus, Ruth, Ezra, Nehemiah, Esther, Haggai, and Malachi - appear to have no poetic lines. Several books in the OT are written either totally (Psalms, Lamentations and Song of Songs) or predominantly in poetry (Job, Proverbs and Ecclesiastes). Moreover, many parts of Isaiah, Jeremiah, Ezekiel and the Minor Prophets also contain poetic writings. While each of these Old Testament books has its own unique tone and style, in general, the poetry they contain can be grouped into 5 basic types: Worship: •Hymns praising God. (Psalm 8) •Psalms of thanksgiving for deliverance. (Psalms 30,124) •Psalms of supplication, voicing complaints and requests. (Psalms 44,64) Teaching: •Proverbs (Ecclesiastes10:18), •Riddles (Proverbs 30:4), •Wise advice (Proverbs 4), •Narrative poems about traditions (Psalms 78, 132), •Narrative poems with a moral (Proverbs 7), •Hymns praising wisdom (Job 28), •Wisdom on the futility and fragility of human life (Ecclesiastes 1:4-9). Prophecy: •Prophecies of reproof and warning (Isaiah 34), •Prophecies of consolation (Isaiah 35). Weddings: •Processionals (Song 3:9-11), 3 •Songs for the bride's preparation (Song 4:1-7), •Epithalamiums outside the wedding chamber (Psalm 127), •Dawn songs greeting newlyweds after the wedding night (Song 6:9-10), •Blessings (Psalm 128). -

Chapter Six the Writings

Eiselein, Goins, Wood / Studying the Bible Chapter Six The Writings Introduction Following the Torah (Instruction) and the Nevi’im (the Former and Latter Prophets), we arrive at the third major division of the Hebrew Bible known as the Ketuvim or the Writings. They are a wide-ranging collection of literary works in various genres, including sacred poetry, practical philosophy or wisdom, paradoxical or speculative wisdom, history, erotic poetry, short stories, personal narratives, apocalyptic literature, and more. For the most part, the texts in this section of the Bible were among the last to be canonized, and they were generally authored later than the texts in the two earlier sections of the Tanakh. There is some older, pre-exilic material in the Writings, in Psalms and Proverbs most notably, but the books collected in this section are predominately from the period following the captivity and Babylonian Exile. (The Exile is the period stretching from 587 BCE, when Jerusalem is destroyed and its inhabitants deported, to 538 BCE, when Cyrus the Emperor of Persia, following his invasion and capture of Babylon, frees the people of Judahnd allows them to return to Jerusalem.) We know that these texts are, for the most part, later for a few different reasons. One clue to their dating has to do with setting and historical context. The histories of Ezra and Nehemiah, for instance, are explicitly set in the Second Temple Period, following the rebuilding of the Temple in Jerusalem, in the era of Persian domination (from about 538 to 332 BCE) but before Alexander the Great of Macedonia (336-323 BCE) conquers Judah/Judea. -

Notes on Song of Solomon 202 1 Edition Dr

Notes on Song of Solomon 202 1 Edition Dr. Thomas L. Constable TITLE In the Hebrew Bible the title of this book is "The Song of Songs." It comes from 1:1. The Septuagint and Vulgate translators adopted this title. The Latin word for song is canticum from which we get the word Canticles, another title for this book. Some English translations have kept the title "Song of Songs" (e.g., NIV, TNIV), but many have changed it to "Song of Solomon" based on 1:1 (e.g., NASB, AV, RSV, NKJV). "The name may be a kind of double entendre: it is the finest of Solomon's songs (in the superlative sense of 'song of songs'), and it is also a single musical work composed of many songs."1 WRITER AND DATE Many references to Solomon throughout the book confirm the claim of 1:1 that Solomon wrote this book (cf. 1:4-5, 12; 3:7, 9, 11; 6:12; 7:5; 8:11- 12; 1 Kings 4:33). He reigned between 971 and 931 B.C. Richard Hess believed the writer is unknown and could have been anyone, even a woman, and that the female heroine viewed and described her lover as a king: as a Solomon.2 Duane Garrett believed that the book was written either "by Solomon" or "for Solomon," by a court poet of Solomon's day.3 Some 1Duane A. Garrett, "Song of Songs," in Song of Songs, Lamentations, p. 26. 2Richard S. Hess, Song of Songs, pp. 34-35, 39, 50, 53, 67. -

Lect17-The Twelve

Lecture 18: Intro to OT Writings and Ruth 1 LECTURE 18a: OT WRITINGS–– The Old Covenant Enjoyed Jason S. DeRouchie, PhD Contents for Lecture 18a I. Introduction 1 A. Purpose 1 B. Two Central Questions 1 C. The Time of Writing and Shaping 1 II. Questions of Sequence 1 A. Various Arrangements of the Writings 1 B. Paul House 2 C. Jason DeRouchie 2 I. Introduction A. Purpose: To show God’s covenant people how to live faithfully in all of life’s circumstances as they hope in God’s faithfulness to fulfill all his kingdom promises. B. Two Central Questions: 1. In the Commentary: How did following Yahweh affect the lives of the remnant throughout the history of the covenant? 2. In the Narrative History: How should Israel’s history be understood by those who truly put their hope in God? C. The Time of Writing and Shaping: from Moses (mid-2nd millennium) to the post-exilic, 2nd temple period (mid-1st millennium) II. Questions of Sequence: A. Various Arrangements of the Writings 1. Baba Bathra 14b (a baraita perhaps dated as early as 2nd century B.C.; found in Babylonian Talmud): Ruth, Psalms, Job, Proverbs, Ecclesiastes, Song of Songs, Lamentations, Daniel, Esther, Ezra-Nehemiah, Chronicles.1 2. Tiberian masoretic codices like the Aleppo Codex (A.D. 930) and Leningrad Codex (A.D. 1008) + several Spanish compilations: Chronicles, Psalms, Job, Proverbs, Ruth, Song of Songs, Ecclesiastes, Lamentations, Esther, Daniel, Ezra-Nehemiah 3. Ashkenazi codices (from medieval Germany): a. The poetic books: Psalms, Job, Proverbs i. Sometimes Job and Proverbs are reversed ii. -

Old Testament

An overview of the books of the Old Testament Saint Mina Coptic Orthodox Church Hamilton, Ontario, Canada An overview of the books of the Old Testament The Bible was written by more than 40 different writers with the inspiration of the Holy Spirit That God inspired men to put it on paper (2 Peter 1:21). Writers From Different Backgrounds The Bible consists of two Testaments: The Old Testament is the period before Christ was born (39+7 books) The New Testament covers the period of Christ's birth and after (27 books) The Old Testament is divided into four basic divisions These divisions are simply man’s attempt at categorization for easy remembrance An Outline of the Old Testament An Outline of the Old Testament The Old Testament consists of 39 books The Deuterocanonical (Second Canonical) Books includes 7 more books and 2 additions Tobit, Judith, Macabees I and II and the additions to the book of Esther Wisdom of Solomon and Wisdom of Jesus the Son of Sirach Baruch and the additions to the book of Daniel (The Song of the three Young Men, Susanna) Quick Timeline of Hebrew Nation The OT Leadership begins with Adam Seth Noah Shem (Egyptians come from Ham’s son Mizraim) Patriarchs Abraham, Isaac, Jacob Moses the exodus from Egypt around 1440 B.C. Joshua Conquest of Canaan around 1400 B.C. Judges Gideon, Samson, Deborah, etc.. Prophet Samuel the Last of the Judges King Saul, Tribe of Benjamin 1043 B.C. King David, (Tribe of Judah) 1025 B.C. King Solomon 985 B.C.