Psalms and Wisdom Literature: an Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wisdom in Daniel and the Origin of Apocalyptic

WISDOM IN DANIEL AND THE ORIGIN OF APOCALYPTIC by GERALD H. WILSON University of Georgia, Athens, Georgia 30602 In this paper, I am concerned with the relationship of the book of Daniel and the biblical wisdom literature. The study draws its impetus from the belief of von Rad that apocalyptic is the "child" of wisdom (1965, II, pp. 304-15). My intent is to test von Rad's claim by a study of wisdom terminology in Daniel in order to determine whether, in fact, that book has its roots in the wisdom tradition. Adequate evidence has been gathered to demonstrate a robust connection between the nar ratives of Daniel 1-6 and mantic wisdom which employs the interpreta tion of dreams, signs and visions (Millier, 1972; Collins, 1975). Here I am concerned to dispell the continuing notion that apocalyptic as ex hibited in Daniel (especially in chapters 7-12) is the product of the same wisdom circles from which came the proverbial biblical books of Proverbs, Ecclesiastes, Job and the later Ben Sirach. 1 I am indebted to the work of Why bray ( 1974), who has dealt exhaustively with the terminology of biblical wisdom, and to the work of Crenshaw (1969), who, among others, has rightly cautioned that the presence of wisdom vocabulary is insufficient evidence of sapiential influence. 2 Whybray (1974, pp. 71-154) distinguishes four categories of wisdom terminology: a) words from the root J:ikm itself; b) other characteristic terms occurring only in the wisdom corpus (5 words); c) words char acteristic of wisdom, but occurring so frequently in other contexts as to render their usefulness in determining sapiential influence questionable (23 words); and d) words characteristic of wisdom, but occurring only occasionally in other OT traditions (10 words). -

The King Who Will Rule the World the Writings (Ketuvim) Mako A

David’s Heir – The King Who Will Rule the World The Writings (Ketuvim) Mako A. Nagasawa Last modified: September 24, 2009 Introduction: The Hero Among ‘the gifts of the Jews’ given to the rest of the world is a hope: A hope for a King who will rule the world with justice, mercy, and peace. Stories and legends from long ago seem to suggest that we are waiting for a special hero. However, it is the larger Jewish story that gives very specific meaning and shape to that hope. The theme of the Writings is the Heir of David, the King who will rule the world. This section of Scripture is very significant, especially taken all together as a whole. For example, not only is the Book of Psalms a personal favorite of many people for its emotional expression, it is a prophetic favorite of the New Testament. The Psalms, written long before Jesus, point to a King. The NT quotes Psalms 2, 16, and 110 (Psalm 110 is the most quoted chapter of the OT by the NT, more frequently cited than Isaiah 53) in very important places to assert that Jesus is the King of Israel and King of the world. The Book of Chronicles – the last book of the Writings – points to a King. He will come from the line of David, and he will rule the world. Who will that King be? What will his life be like? Will he usher in the life promised by God to Israel and the world? If so, how? And, what will he accomplish? How worldwide will his reign be? How will he defeat evil on God’s behalf? Those are the major questions and themes found in the Writings. -

Book Introductions: Job – Malachi

Book Introductions: Job - Malachi Job offers a hard look at suffering from both the human and divine perspec7ve. In the first two chapters we catch a glimpse of the spiritual background as Satan and God discuss righteous Job (and then Satan is allowed to bring disasters into Job’s life). From chapter 3 on we see Job responding, without the perspec7ve of chapters 1-2. Much of the book is a cycle of debate between Job and three men, plus a fourth nearer the end. The “friends” are clear that suffering is a consequence for sin, so Job must be a terrible sinner. Job calls on God to disclose his righteousness. Where does wisdom come from in the harsh reali7es of life? It cannot come from human thought, it must come from God. Finally God speaks and Job is humbled by dozens of ques7ons from the Almighty One. God is God. Job is dumbfounded. Finally God restores Job’s fortunes again. There is no easy answer for undeserved suffering, but Job urges us to look heavenwards in every circumstance. Psalms is a collec7on of collec7ons of poetry, many wriSen by King David. Psalms 1 and 2 act as an introduc7on to the book. The first psalm contrasts the enduring blessing of the believer who meditates on God’s Word with the flee7ng and vain eXistence of the wicked. Yet the book clearly demonstrates that life usually doesn’t seem to work out as it should – the wicked seem to prosper, the righteous seem to suffer, things are not right. So the various psalmists ask ques7ons, complain, occasionally have an emo7onal outburst. -

Syllabus, Deuterocanonical Books

The Deuterocanonical Books (Tobit, Judith, 1 & 2 Maccabees, Wisdom, Sirach, Baruch, and additions to Daniel & Esther) Caravaggio. Saint Jerome Writing (oil on canvas), c. 1605-1606. Galleria Borghese, Rome. with Dr. Bill Creasy Copyright © 2021 by Logos Educational Corporation. All rights reserved. No part of this course—audio, video, photography, maps, timelines or other media—may be reproduced or transmitted in any form by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage or retrieval devices without permission in writing or a licensing agreement from the copyright holder. Scripture texts in this work are taken from the New American Bible, revised edition © 2010, 1991, 1986, 1970 Confraternity of Christian Doctrine, Washington, D.C. and are used by permission of the copyright owner. All Rights Reserved. No part of the New American Bible may be reproduced in any form without permission in writing from the copyright owner. 2 The Deuterocanonical Books (Tobit, Judith, 1 & 2 Maccabees, Wisdom, Sirach, Baruch, and additions to Daniel & Esther) Traditional Authors: Various Traditional Dates Written: c. 250-100 B.C. Traditional Periods Covered: c. 250-100 B.C. Introduction The Deuterocanonical books are those books of Scripture written (for the most part) in Greek that are accepted by Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox churches as inspired, but they are not among the 39 books written in Hebrew accepted by Jews, nor are they accepted as Scripture by most Protestant denominations. The deuterocanonical books include: • Tobit • Judith • 1 Maccabees • 2 Maccabees • Wisdom (also called the Wisdom of Solomon) • Sirach (also called Ecclesiasticus) • Baruch, (including the Letter of Jeremiah) • Additions to Daniel o “Prayer of Azariah” and the “Song of the Three Holy Children” (Vulgate Daniel 3: 24- 90) o Suzanna (Daniel 13) o Bel and the Dragon (Daniel 14) • Additions to Esther Eastern Orthodox churches also include: 3 Maccabees, 4 Maccabees, 1 Esdras, Odes (which include the “Prayer of Manasseh”) and Psalm 151. -

Proverbs Part One: Ten Instructions for the Wisdom Seeker

PROVERBS 67 Part One: Ten Instructions for the Wisdom Seeker Chapters 1-9 Introduction.Proverbs is generally regarded as the COMMENTARY book that best characterizes the Wisdom tradition. It is presented as a “guide for successful living.” Its PART 1: Ten wisdom instructions (Chapters 1-9) primary purpose is to teach wisdom. In chapters 1-9, we find a set of ten instructions, A “proverb” is a short saying that summarizes some aimed at persuading young minds about the power of truths about life. Knowing and practicing such truths wisdom. constitutes wisdom—the ability to navigate human relationships and realities. CHAPTER 1: Avoid the path of the wicked; Lady Wisdom speaks The Book of Proverbs takes its name from its first verse: “The proverbs of Solomon, the son of David.” “That men may appreciate wisdom and discipline, Solomon is not the author of this book which is a may understand words of intelligence; may receive compilation of smaller collections of sayings training in wise conduct….” (vv 2-3) gathered up over many centuries and finally edited around 500 B.C. “The fear of the Lord is the beginning of knowledge….” (v.7) In Proverbs we will find that certain themes or topics are dealt with several times, such as respect for Verses 1-7.In these verses, the sage or teacher sets parents and teachers, control of one’s tongue, down his goal: to instruct people in the ways of cautious trust of others, care in the selection of wisdom. friends, avoidance of fools and women with loose morals, practice of virtues such as humility, The ten instructions in chapters 1-9 are for those prudence, justice, temperance and obedience. -

Hom 9413 Preaching Various Literary Genre

HOM 9413 PREACHING VARIOUS LITERARY GENRE Syllabus Pre-campus Period: April 1—June 25, 2011, Campus Period: June 27—July 1, 2011 Post-Campus Period: July 2, 2011—August 26, 2011 William J. Larkin, Instructor Contact Information Office: #224 Schuster Mailing Address: CIU Seminary and School of Missions 7435 Monticello Road Columbia, SC 29230-3122 Phone: (O) 803-807-5334 (H) 803-798-6888 Email: [email protected] I. COURSE DESCRIPTION A study of the appropriation of Scripture's rich literary texture for preaching today. The student will investigate literary genres of Old Testament law, narrative, prophecy, praise and wisdom and New Testament narrative, parable, epistle, speech, and prophetic-apocalyptic and their promise for preaching. He will develop and execute, from study through preached sermon, an exegetical- homiletical method designed to produce effective sermons which embody the literary-rhetorical moves of the various Biblical genre. II. REQUIRED TEXTS Arthurs, Jeffrey D. Preaching with Variety: How to Recreate the Dynamics of Biblical Genre . Grand Rapids: Kregel, 2007. Bailey , James L. and Lyle D. Vanderbroek. Literary Forms in the New Testament: A Handbook . Louisville, KY: Westminster/John Knox, 1992. Kaiser, Jr., Walter C. Preaching and Teaching from the Old Testament: A Guide for the Church . Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2003. Larkin, William J. Greek is Great Gain: A Method for Exegesis and Exposition . Eugene, OR: Wipf and Stock, 2008. “Appendix: Additional Genre and Literary Form Analysis Procedures” (available at course website under “Resources”). Sandy, D. Brent and Ronald L. Giese, eds. Cracking Old Testament Codes: A Guide to Interpreting the Literary Genres of the Old Testament . -

Literary Techniques

Literary Techniques: The following literary techniques are introduced in sequence at various points in the year, and then reviewed and practiced as the year progresses. Understanding how formal techniques of literature are used by an author to present his or her content in a particular way involves use of the fourth level or sixth level of cognitive tasks in Bloom’s taxonomy, and involves cross- curricular integration as the same sort of questions are asked in Literature class as well. For each technique below, the number in parenthesis constitutes the class in which the technique is introduced (the first time we reach it in our reading of the text). Each one is reviewed multiple times afterwards. 1. Parable (2) 2. Metaphor (2) 3. Simile (2) 4. Leitwort (2) – the repeated use of a non-typical word in a section for the purpose of conveying a theme. 5. Biblical Parallelism (4) – the poetic technique used in the Bible where an idea is presented twice, in two consecutive phrases, using different words. 6. Irony (4) 7. Use of Structure (6) – the decision to arrange the text of a large passage in a stylized way, often using a repeated refrain or chorus to divide the large text into subsections. 8. Personification (11) 9. Selection of Genre (11) – the author’s decision to write using a particular genre (such as poetry, prose, etc.) instead of another. 10. Alliteration (11) 11. Pun (11) 12. Word Choice (14) – the author’s decision to use one particular word, when another, more common word may have been more appropriate. -

The Book of Proverbs: Wisdom for Life August 5Th, 2015 Text

The Book of Proverbs: Wisdom for Life August 5th, 2015 Text: Proverbs 1:1-7 Background/Theme: The book of Proverbs was written mainly by Solomon (known as Israel’s wisest king) yet some of the later sections were written by men named Lemuel and Agur (See Prov. 1:1). It was written during Solomon’s reign (970-930 B.C.). Solomon asked God for wisdom to rule God’s nation and God granted it (1 Kings 3:6-14). Proverbs along with Job, Psalms, Ecclesiastes, and Song of Solomon are known as the writings or “Wisdom Books” addressing practical living before God. The theme of Proverbs is wisdom (the skilled and right use of knowledge). The main purpose of this book is to teach wisdom to God’s people through the use of proverbs. The word Proverb means “to be like.” Therefore, Proverbs are short statements, which compare and contrast common, concrete images with life’s most profound truth. They are practical and point the way to godly character. These proverbs address subjects such as: life, family, friends, good judgment, and distinctions between the wise and foolish man. Proverbs is not a do-it-yourself success kit for the greedy but a guidebook for the godly. This starts with fearing the LORD. Memory Verse: Prov. 1:7 Outline: Ch 1-9-Solomon writes wisdom for younger people. Ch 10-24 - There is wisdom on various topics that apply to the average person. Ch 25-31 - Wisdom for leaders is provided. Tips for reading proverbs-Proverbs are statements of general truth and must not be taken as divine promises (Prov. -

Church Holy Books 1. Holy Bible: Old Testament

Church Holy Books •How many books does the Church use? •What are they for and when are they used? 1. Holy Bible: Old Testament 39 Books: Books of the LAW (5): – Genesis – Exodus – Leviticus – Numbers – Deuteronomy 1 1. Holy Bible: Old Testament Historical Books (12): – Joshua – Judges – Ruth – 1 & 2 Samuel – 1 & 2 Kings – 1 & 2 Chronicles – Ezra – Nehemiah – Esther 1. Holy Bible: Old Testament Poetic Books (5): – Job – Psalms – Proverbs – Ecclesiastes – Song of Songs 2 1. Holy Bible: Old Testament Major Prophets (5): – Isaiah – Jeremiah – Lamentations of Jeremiah – Ezekiel – Daniel 1. Holy Bible: Old Testament Minor Prophets (12): Hosea Nahum Joel Habakkuk Amos Zephaniah Obadiah Haggai Jonah Zechariah Micah Malachi 3 1. Holy Bible “All Scripture is given by inspiration of God, and is profitable for doctrine, for reproof, for correction, for instruction in righteousness” (2 Timothy 3:16) Most important of all books All the other books are based upon It and inspired by It Our Church is an entirely Biblical Church relying on God’s inspired Word for our spiritual nourishment 1. Holy Bible: Old Testament Easy way to remember: – 5 – 12 – 5 – 5 – 12 – Law (5) – Historical (12) – Poetic (5) – Major Prophets (5) – Minor Prophets (12) 4 1. Holy Bible: Old Testament More Old Testament Books Deuterocanonical Books 10 additional books or parts of books were removed from the Protestant translation of the Bible, but exist in the Hebrew, Septuagint (Greek) and Vulgate (Latin) 1. Holy Bible: Old Testament According to the Coptic tradition, they are: – Tobit – Judith – 1 and 2 Maccabees – Wisdom – Sirach – Baruch – Rest of Esther – Additions to Daniel – Psalm 151 5 1. -

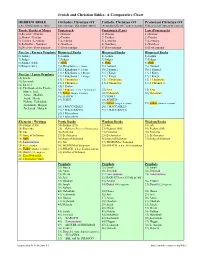

Hebrew and Christian Bibles: a Comparative Chart

Jewish and Christian Bibles: A Comparative Chart HEBREW BIBLE Orthodox Christian OT Catholic Christian OT Protestant Christian OT (a.k.a. TaNaK/Tanakh or Mikra) (based on longer LXX; various editions) (Alexandrian LXX, with 7 deutero-can. bks) (Cath. order, but 7 Apocrypha removed) Torah / Books of Moses Pentateuch Pentateuch (Law) Law (Pentateuch) 1) Bereshit / Genesis 1) Genesis 1) Genesis 1) Genesis 2) Shemot / Exodus 2) Exodus 2) Exodus 2) Exodus 3) VaYikra / Leviticus 3) Leviticus 3) Leviticus 3) Leviticus 4) BaMidbar / Numbers 4) Numbers 4) Numbers 4) Numbers 5) Devarim / Deuteronomy 5) Deuteronomy 5) Deuteronomy 5) Deuteronomy Nevi’im / Former Prophets Historical Books Historical Books Historical Books 6) Joshua 6) Joshua 6) Joshua 6) Joshua 7) Judges 7) Judges 7) Judges 7) Judges 8) Samuel (1&2) 8) Ruth 8) Ruth 8) Ruth 9) Kings (1&2) 9) 1 Kingdoms (= 1 Sam) 9) 1 Samuel 9) 1 Samuel 10) 2 Kingdoms (= 2 Sam) 10) 2 Samuel 10) 2 Samuel 11) 3 Kingdoms (= 1 Kings) 11) 1 Kings 11) 1 Kings Nevi’im / Latter Prophets 12) 4 Kingdoms (= 2 Kings) 12) 2 Kings 12) 2 Kings 10) Isaiah 13) 1 Chronicles 13) 1 Chronicles 13) 1 Chronicles 11) Jeremiah 14) 2 Chronicles 14) 2 Chronicles 14) 2 Chronicles 12) Ezekiel 15) 1 Esdras 13) The Book of the Twelve: 16) 2 Esdras (= Ezra + Nehemiah) 15) Ezra 15) Ezra Hosea, Joel, 17) Esther (longer version) 16) Nehemiah 16) Nehemiah Amos, Obadiah, 18) JUDITH 17) TOBIT Jonah, Micah, 19) TOBIT 18) JUDITH Nahum, Habakkuk, 19) Esther (longer version) 17) Esther (shorter version) Zephaniah, Haggai, 20) 1 MACCABEES 20) -

The Book of Proverbs Is Not Mysterious, Nor Does It Leave Its Readers Wondering As to Its Purpose

INTRODUCTION The book of Proverbs is not mysterious, nor does it leave its readers wondering as to its purpose. At the very outset we are clearly told the author’s intention. The purpose of these proverbs is to teach people wisdom and discipline, and to help them understand wise sayings. Through these proverbs, people will receive instruction in discipline, good conduct, and doing what is right, just, and fair. These proverbs will make the simpleminded clever. They will give knowledge and purpose to young people. Let those who are wise listen to these proverbs and become even wiser. And let those who understand receive guidance by exploring the depth of meaning in these proverbs, parables, wise sayings, and riddles. NLT, 1:2-6 The book of Proverbs is simply about godly wisdom, how to attain it, and how to use it in everyday living. In Proverbs the words wise or wisdom are used roughly125 times. The wisdom that is spoken of in these proverbs is bigger than raw intelligence or advanced education. This is a wisdom that has to do skillful living. It speaks of understanding how to act and be competent in a variety of life situations. Dr. Roy Zuck’s definition of wisdom is to the point. Wisdom means being skillful and successful in one’s relationships and responsibilities . observing and following the Creator’s principles of order in the moral universe. (Zuck, Biblical Theology of the Old Testament, p. 232) The wisdom of Proverbs is not theoretical.1 It assumes that there is a right way and a wrong way to live. -

Guide to Reading Nevi'im and Ketuvim" Serves a Dual Purpose: (1) It Gives You an Overall Picture, a Sort of Textual Snapshot, of the Book You Are Reading

A Guide to Reading Nevi’im and Ketuvim By Seth (Avi) Kadish Contents (All materials are in Hebrew only unless otherwise noted.) Midrash Introduction (English) How to Use the Guide Sheets (English) Month 1: Yehoshua & Shofetim (1 page each) Month 2: Shemuel Month 3: Melakhim Month 4: Yeshayahu Month 5: Yirmiyahu (2 pages) Month 6: Yehezkel Month 7: Trei Asar (2 pages) Month 8: Iyyov Month 9: Mishlei & Kohelet Month 10: Megillot (except Kohelet) & Daniel Months 11-12: Divrei HaYamim & Ezra-Nehemiah (3 pages) Chart for Reading Sefer Tehillim (six-month cycle) Chart for Reading Sefer Tehillim (leap year) Guide to Reading the Five Megillot in the Synagogue Sources and Notes (English) A Guide to Reading Nevi’im and Ketuvim Introduction What purpose did the divisions serve? They let Moses pause to reflect between sections and between topics. The matter may be inferred: If a person who heard the Torah directly from the Holy One, Blessed be He, who spoke with the Holy Spirit, must pause to reflect between sections and between topics, then this is true all the more so for an ordinary person who hears it from another ordinary person. (On the parashiyot petuhot and setumot. From Dibbura de-Nedava at the beginning of Sifra.) A Basic Problem with Reading Tanakh Knowing where to stop to pause and reflect is not a trivial detail when it comes to reading Tanakh. In my own study, simply not knowing where to start reading and where to stop kept me, for many years, from picking up a Tanakh and reading the books I was unfamiliar with.