Studies in Biblical Poetry the Collected Notes of C.A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Notes on Psalms 2015 Edition Dr

Notes on Psalms 2015 Edition Dr. Thomas L. Constable Introduction TITLE The title of this book in the Hebrew Bible is Tehillim, which means "praise songs." The title adopted by the Septuagint translators for their Greek version was Psalmoi meaning "songs to the accompaniment of a stringed instrument." This Greek word translates the Hebrew word mizmor that occurs in the titles of 57 of the psalms. In time the Greek word psalmoi came to mean "songs of praise" without reference to stringed accompaniment. The English translators transliterated the Greek title resulting in the title "Psalms" in English Bibles. WRITERS The texts of the individual psalms do not usually indicate who wrote them. Psalm 72:20 seems to be an exception, but this verse was probably an early editorial addition, referring to the preceding collection of Davidic psalms, of which Psalm 72 was the last.1 However, some of the titles of the individual psalms do contain information about the writers. The titles occur in English versions after the heading (e.g., "Psalm 1") and before the first verse. They were usually the first verse in the Hebrew Bible. Consequently the numbering of the verses in the Hebrew and English Bibles is often different, the first verse in the Septuagint and English texts usually being the second verse in the Hebrew text, when the psalm has a title. ". there is considerable circumstantial evidence that the psalm titles were later additions."2 However, one should not understand this statement to mean that they are not inspired. As with some of the added and updated material in the historical books, the Holy Spirit evidently led editors to add material that the original writer did not include. -

A Resource Guide for Studying and Appropriating the Psalms

Leaven Volume 7 Issue 3 I Lift Up My Soul Article 10 1-1-1999 I Lift Up My Soul: A Resource Guide for Studying and Appropriating the Psalms Paul Watson Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.pepperdine.edu/leaven Part of the Biblical Studies Commons, Christianity Commons, and the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Watson, Paul (1999) "I Lift Up My Soul: A Resource Guide for Studying and Appropriating the Psalms," Leaven: Vol. 7 : Iss. 3 , Article 10. Available at: https://digitalcommons.pepperdine.edu/leaven/vol7/iss3/10 This Resource Guide is brought to you for free and open access by the Religion at Pepperdine Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Leaven by an authorized editor of Pepperdine Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]. Watson: I Lift Up My Soul: A Resource Guide for Studying and Appropriatin 160 Leaven, Summer, 1999 ILift Up My Soul: A Resource Guide for Studying and Appropriating the Psal By Paul Watson We are experiencing among our not to suggest that oldel"'tesources the new Interpretation Biblical people a renewed and increased are not also valuable); and third, Studies series. Intended for use in interest in the psalms, which is most that they be readable and accessible congregational Bible classes, this is encouraging. We are turning to the to any serious student of the psalms. a ten-unit study guide. The first two psalms in many different settings-- I hope that you will find these units provide a general overview of in classes and small groups, in the resources as helpful and insightful the psalms; the remaining eight pulpit, in private devotional mo- as I have. -

Psalms Psalm

Cultivate - PSALMS PSALM 126: We now come to the seventh of the "Songs of Ascent," a lovely group of Psalms that God's people would sing and pray together as they journeyed up to Jerusalem. Here in this Psalm they are praying for the day when the Lord would "restore the fortunes" of God's people (vs.1,4). 126 is a prayer for spiritual revival and reawakening. The first half is all happiness and joy, remembering how God answered this prayer once. But now that's just a memory... like a dream. They need to be renewed again. So they call out to God once more: transform, restore, deliver us again. Don't you think this is a prayer that God's people could stand to sing and pray today? Pray it this week. We'll pray it together on Sunday. God is here inviting such prayer; he's even putting the very words in our mouths. PSALM 127: This is now the eighth of the "Songs of Ascent," which God's people would sing on their procession up to the temple. We've seen that Zion / Jerusalem / The House of the Lord are all common themes in these Psalms. But the "house" that Psalm 127 refers to (in v.1) is that of a dwelling for a family. 127 speaks plainly and clearly to our anxiety-ridden thirst for success. How can anything be strong or successful or sufficient or secure... if it does not come from the Lord? Without the blessing of the Lord, our lives will come to nothing. -

Church Holy Books 1. Holy Bible: Old Testament

Church Holy Books •How many books does the Church use? •What are they for and when are they used? 1. Holy Bible: Old Testament 39 Books: Books of the LAW (5): – Genesis – Exodus – Leviticus – Numbers – Deuteronomy 1 1. Holy Bible: Old Testament Historical Books (12): – Joshua – Judges – Ruth – 1 & 2 Samuel – 1 & 2 Kings – 1 & 2 Chronicles – Ezra – Nehemiah – Esther 1. Holy Bible: Old Testament Poetic Books (5): – Job – Psalms – Proverbs – Ecclesiastes – Song of Songs 2 1. Holy Bible: Old Testament Major Prophets (5): – Isaiah – Jeremiah – Lamentations of Jeremiah – Ezekiel – Daniel 1. Holy Bible: Old Testament Minor Prophets (12): Hosea Nahum Joel Habakkuk Amos Zephaniah Obadiah Haggai Jonah Zechariah Micah Malachi 3 1. Holy Bible “All Scripture is given by inspiration of God, and is profitable for doctrine, for reproof, for correction, for instruction in righteousness” (2 Timothy 3:16) Most important of all books All the other books are based upon It and inspired by It Our Church is an entirely Biblical Church relying on God’s inspired Word for our spiritual nourishment 1. Holy Bible: Old Testament Easy way to remember: – 5 – 12 – 5 – 5 – 12 – Law (5) – Historical (12) – Poetic (5) – Major Prophets (5) – Minor Prophets (12) 4 1. Holy Bible: Old Testament More Old Testament Books Deuterocanonical Books 10 additional books or parts of books were removed from the Protestant translation of the Bible, but exist in the Hebrew, Septuagint (Greek) and Vulgate (Latin) 1. Holy Bible: Old Testament According to the Coptic tradition, they are: – Tobit – Judith – 1 and 2 Maccabees – Wisdom – Sirach – Baruch – Rest of Esther – Additions to Daniel – Psalm 151 5 1. -

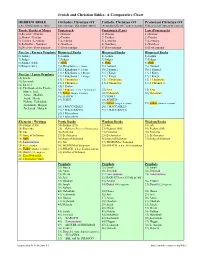

Hebrew and Christian Bibles: a Comparative Chart

Jewish and Christian Bibles: A Comparative Chart HEBREW BIBLE Orthodox Christian OT Catholic Christian OT Protestant Christian OT (a.k.a. TaNaK/Tanakh or Mikra) (based on longer LXX; various editions) (Alexandrian LXX, with 7 deutero-can. bks) (Cath. order, but 7 Apocrypha removed) Torah / Books of Moses Pentateuch Pentateuch (Law) Law (Pentateuch) 1) Bereshit / Genesis 1) Genesis 1) Genesis 1) Genesis 2) Shemot / Exodus 2) Exodus 2) Exodus 2) Exodus 3) VaYikra / Leviticus 3) Leviticus 3) Leviticus 3) Leviticus 4) BaMidbar / Numbers 4) Numbers 4) Numbers 4) Numbers 5) Devarim / Deuteronomy 5) Deuteronomy 5) Deuteronomy 5) Deuteronomy Nevi’im / Former Prophets Historical Books Historical Books Historical Books 6) Joshua 6) Joshua 6) Joshua 6) Joshua 7) Judges 7) Judges 7) Judges 7) Judges 8) Samuel (1&2) 8) Ruth 8) Ruth 8) Ruth 9) Kings (1&2) 9) 1 Kingdoms (= 1 Sam) 9) 1 Samuel 9) 1 Samuel 10) 2 Kingdoms (= 2 Sam) 10) 2 Samuel 10) 2 Samuel 11) 3 Kingdoms (= 1 Kings) 11) 1 Kings 11) 1 Kings Nevi’im / Latter Prophets 12) 4 Kingdoms (= 2 Kings) 12) 2 Kings 12) 2 Kings 10) Isaiah 13) 1 Chronicles 13) 1 Chronicles 13) 1 Chronicles 11) Jeremiah 14) 2 Chronicles 14) 2 Chronicles 14) 2 Chronicles 12) Ezekiel 15) 1 Esdras 13) The Book of the Twelve: 16) 2 Esdras (= Ezra + Nehemiah) 15) Ezra 15) Ezra Hosea, Joel, 17) Esther (longer version) 16) Nehemiah 16) Nehemiah Amos, Obadiah, 18) JUDITH 17) TOBIT Jonah, Micah, 19) TOBIT 18) JUDITH Nahum, Habakkuk, 19) Esther (longer version) 17) Esther (shorter version) Zephaniah, Haggai, 20) 1 MACCABEES 20) -

Psalm 113-114 Psalms Praising God for His Deliverance Psalms 113-118

Finding Yourself in the Psalms Psalm 113-114 Psalms Praising God for His Deliverance Psalms 113-118 - The HALLEL. Recited during PASSOVER, TABERNACLES, PENTECOST 113-114 Sung at the Passover Meal, after the 2nd CUP 113 - 3 Stanzas, 3 verses each. - Trinity - Praise and Deliverance 114 - Deliverance from Egypt I. Praise Him EVERYWHERE. 113:1-3 II. Praise Him EVERYONE. 113:4-6 III. The Deliverer of the NEEDY. 113:7-9 A. 113:7. “Dust” (Psalm 103:14) "for he knows how we are formed, he remembers that we are dust." B. “When you’re as low as you can get, God is there waiting to deliver you.” C. (Psalm 40:1-3) "I waited patiently for the Lord; he turned to me and heard my cry. He lifted me out of the slimy pit, out of the mud and mire; he set my feet on a rock and gave me a firm place to stand. He put a new song in my mouth, a hymn of praise to our God. Many will see and fear and put their trust in the Lord." D. The Songs of HANNAH and MARY. 113:9 1. (1 Samuel 2:8) "He raises the poor from the dust and lifts the needy from the ash heap; he seats them with princes and has them inherit a throne of honor. “For the foundations of the earth are the Lord’s; upon them he has set the world." 2. (Luke 1:52) "He has brought down rulers from their thrones but has lifted up the humble." 3. -

Ecclesiastes: Koheleth's Quest for Life's Meaning

ECCLESIASTES: KOHELETH'S QUEST FOR LIFE'S MEANING by Weston W. Fields Submitted in partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree of Master of Theology in Grace Theological Seminary May 1975 Digitized by Ted Hildebrandt and Dr. Perry Phillips, Gordon College, 2007. PREFACE It was during a series of lectures given in Grace Theological Seminary by Professor Thomas V. Taylor on the book of Ecclesiastes that the writer's own interest in the book was first stirred. The words of Koheleth are remark- ably suited to the solution of questions and problems which arise for the Christian in the twentieth century. Indeed, the message of the book is so appropriate for the contem- porary world, and the book so cogently analyzes the purpose and value of life, that he who reads it wants to study it; and he who studies it finds himself thoroughly attached to it: one cannot come away from the book unchanged. For the completion of this study the writer is greatly indebted to his advisors, Dr. John C. Whitcomb, Jr. and Professor James R. Battenfield, without whose patient help and valuable suggestions this thesis would have been considerably impoverished. To my wife Beverly, who has once again patiently and graciously endured a writing project, I say thank you. TABLE OF CONTENTS GRADE PAGE iii PREFACE iv TABLE OF CONTENTS v Chapter I. INTRODUCTION AND STATEMENT OF PURPOSE 1 II. THE TITLE 5 Translation 5 Meaning of tl,h,qo 6 Zimmermann's Interpretation 7 Historical Interpretations 9 Linguistic Analysis 9 What did Solomon collect? 12 Why does Solomon bear this name? 12 The feminine gender 13 Conclusion 15 III. -

Guide to Reading Nevi'im and Ketuvim" Serves a Dual Purpose: (1) It Gives You an Overall Picture, a Sort of Textual Snapshot, of the Book You Are Reading

A Guide to Reading Nevi’im and Ketuvim By Seth (Avi) Kadish Contents (All materials are in Hebrew only unless otherwise noted.) Midrash Introduction (English) How to Use the Guide Sheets (English) Month 1: Yehoshua & Shofetim (1 page each) Month 2: Shemuel Month 3: Melakhim Month 4: Yeshayahu Month 5: Yirmiyahu (2 pages) Month 6: Yehezkel Month 7: Trei Asar (2 pages) Month 8: Iyyov Month 9: Mishlei & Kohelet Month 10: Megillot (except Kohelet) & Daniel Months 11-12: Divrei HaYamim & Ezra-Nehemiah (3 pages) Chart for Reading Sefer Tehillim (six-month cycle) Chart for Reading Sefer Tehillim (leap year) Guide to Reading the Five Megillot in the Synagogue Sources and Notes (English) A Guide to Reading Nevi’im and Ketuvim Introduction What purpose did the divisions serve? They let Moses pause to reflect between sections and between topics. The matter may be inferred: If a person who heard the Torah directly from the Holy One, Blessed be He, who spoke with the Holy Spirit, must pause to reflect between sections and between topics, then this is true all the more so for an ordinary person who hears it from another ordinary person. (On the parashiyot petuhot and setumot. From Dibbura de-Nedava at the beginning of Sifra.) A Basic Problem with Reading Tanakh Knowing where to stop to pause and reflect is not a trivial detail when it comes to reading Tanakh. In my own study, simply not knowing where to start reading and where to stop kept me, for many years, from picking up a Tanakh and reading the books I was unfamiliar with. -

Psalm 75 — God Will Judge

Psalms, Hymns, and Spiritual Songs: The Master Musician’s Melodies Bereans Sunday School Placerita Baptist Church 2006 by William D. Barrick, Th.D. Professor of OT, The Master’s Seminary Psalm 75 — God Will Judge 1.0 Introducing Psalm 75 y Psalms 50 and 73–83 attribute their composition to Asaph. 9 There could be more than one Asaph. 9 “Asaph” might sometimes refer to a descendant of Asaph (cp. 2 Chron 35:15). y Psalm 75 shares themes and phraseology with “Hannah’s Song” (1 Samuel 2:1-10) and Mary’s “Magnificat” (Luke 1:46-55). y Placement of Psalm 75 following 74 highlights common emphases: 9 The psalmist prays for God to act (74:22-23) and He does (75:7, 10). 9 God is King (74:12) and God is Judge (75:2, 7). 9 Question of “How long?” (74:10) will be answered at “an appointed time” (75:2). 9 Both “meeting places” (74:8) and “appointed time” (75:2) translate the same Hebrew word (74:8 is the plural). 9 “Your name” occurs in both psalms (74:7, 10, 18, 21; 75:1). 2.0 Reading Psalm 75 (NAU) 75:1 A Psalm of Asaph, a Song. We give thanks to You, O God, we give thanks, For Your name is near; Men declare Your wondrous works. 75:2 “When I select an appointed time, It is I who judge with equity. 75:3 “The earth and all who dwell in it melt; It is I who have firmly set its pillars. Selah. Psalms, Hymns, and Spiritual Songs 2 Barrick, Placerita Baptist Church 2006 75:4 “I said to the boastful, ‘Do not boast,’ And to the wicked, ‘Do not lift up the horn; 75:5 “‘Do not lift up your horn on high, Do not speak with insolent pride.’” 75:6 For not from the east, nor from the west, Nor from the desert comes exaltation; 75:7 But God is the Judge; He puts down one and exalts another. -

Congressional Record—House H9104

H9104 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — HOUSE November 20, 2019 was inducted into the San Diego Wom- most difficult circumstances. And her throughout the world where such free- en’s Hall of Fame for her work in co- death reminds us that transgender peo- doms do not exist. founding the United Domestic Workers ple are under attack and must have Americans have the right under our of America. equal protection under the law. wonderful system of government to re- With her passing, the State of Cali- f spect and study the Bible or any other fornia and our Nation suffered a tre- system of belief that they so choose or mendous loss. She will be remembered HONORING TOM VASQUEZ even none at all. That is the beauty of for her ‘‘si, se puede’’ attitude and for (Mr. GARCI´A of Illinois asked and the American way, and I believe it goes exemplifying the meaning of her Swa- was given permission to address the all the way back to the Bible. hili given name, Fahari, which means House for 1 minute and to revise and In 1941, President Franklin Delano magnificent, and magnificent she was. extend his remarks.) Roosevelt declared the week of f Mr. GARCI´A of Illinois. Mr. Speaker, Thanksgiving to be National Bible SUPPORT BIPARTISAN PATH FOR today, I rise to honor the memory of Week. The National Bible Association USMCA my dear friend Tom Vasquez, who and the U.S. Conference of Bishops have designated the specific days of (Ms. KENDRA S. HORN of Oklahoma passed away on July 23. -

Old Testament Basics LESSON 08 of 10 Old Testament Poetry

OT128 Old Testament Basics LESSON 08 of 10 Old Testament Poetry Dr. Sid Buzzell Experience: Dean of Christian University GlobalNet Introduction In this lesson, we study some of the Bible’s most profound and treasured literature. In fact it’s some of the most beautiful literature written anywhere. In this lesson, we will study Israel’s Old Testament poetry. There are five Old Testament books—Job, Psalms, Proverbs, the Song of Solomon, and Lamentations— that are written entirely or almost entirely in poetic form. Many narrative books contain poetry and so do all but two of the prophetic books. Isaiah contains some of the most magnificent poetry in all of the Old Testament. From Genesis to Malachi, the Old Testament is enriched by poetry. Characteristics of Old Testament Poetry Poetry is distilled language. While prose is usually explicit in its form, poetry is written in such a way that the reader has to interact with the writer. The message is written so the reader has to discover it by working with the poem’s construction. When writing in distilled language, the poet works very hard to find just the right word to make the poem work. He or she has to make the lines in the poetic verses interact with each other. The poet writes with the expectation that the reader work the meaning out of the poem and that truth discovered is more powerful than truth given. So if you try to read Old Testament poetry quickly, casually, easily, it won’t work. You have to get into the process. -

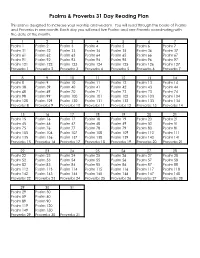

Psalms & Proverbs 31 Day Reading Plan

Psalms & Proverbs 31 Day Reading Plan This plan is designed to increase your worship and wisdom. You will read through the books of Psalms and Proverbs in one month. Each day you will read five Psalms and one Proverb coordinating with the date of the month. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Psalm 1 Psalm 2 Psalm 3 Psalm 4 Psalm 5 Psalm 6 Psalm 7 Psalm 31 Psalm 32 Psalm 33 Psalm 34 Psalm 35 Psalm 36 Psalm 37 Psalm 61 Psalm 62 Psalm 63 Psalm 64 Psalm 65 Psalm 66 Psalm 67 Psalm 91 Psalm 92 Psalm 93 Psalm 94 Psalm 95 Psalm 96 Psalm 97 Psalm 121 Psalm 122 Psalm 123 Psalm 124 Psalm 125 Psalm 126 Psalm 127 Proverbs 1 Proverbs 2 Proverbs 3 Proverbs 4 Proverbs 5 Proverbs 6 Proverbs 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Psalm 8 Psalm 9 Psalm 10 Psalm 11 Psalm 12 Psalm 13 Psalm 14 Psalm 38 Psalm 39 Psalm 40 Psalm 41 Psalm 42 Psalm 43 Psalm 44 Psalm 68 Psalm 69 Psalm 70 Psalm 71 Psalm 72 Psalm 73 Psalm 74 Psalm 98 Psalm 99 Psalm 100 Psalm 101 Psalm 102 Psalm 103 Psalm 104 Psalm 128 Psalm 129 Psalm 130 Psalm 131 Psalm 132 Psalm 133 Psalm 134 Proverbs 8 Proverbs 9 Proverbs 10 Proverbs 11 Proverbs 12 Proverbs 13 Proverbs 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 Psalm 15 Psalm 16 Psalm 17 Psalm 18 Psalm 19 Psalm 20 Psalm 21 Psalm 45 Psalm 46 Psalm 47 Psalm 48 Psalm 49 Psalm 50 Psalm 51 Psalm 75 Psalm 76 Psalm 77 Psalm 78 Psalm 79 Psalm 80 Psalm 81 Psalm 105 Psalm 106 Psalm 107 Psalm 108 Psalm 109 Psalm 110 Psalm 111 Psalm 135 Psalm 136 Psalm 137 Psalm 138 Psalm 139 Psalm 140 Psalm 141 Proverbs 15 Proverbs 16 Proverbs 17 Proverbs 18 Proverbs 19 Proverbs 20 Proverbs 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 Psalm 22 Psalm 23 Psalm 24 Psalm 25 Psalm 26 Psalm 27 Psalm 28 Psalm 52 Psalm 53 Psalm 54 Psalm 55 Psalm 56 Psalm 57 Psalm 58 Psalm 82 Psalm 83 Psalm 84 Psalm 85 Psalm 86 Psalm 87 Psalm 88 Psalm 112 Psalm 113 Psalm 114 Psalm 115 Psalm 116 Psalm 117 Psalm 118 Psalm 142 Psalm 143 Psalm 144 Psalm 145 Psalm 146 Psalm 147 Psalm 148 Proverbs 22 Proverbs 23 Proverbs 24 Proverbs 25 Proverbs 26 Proverbs 27 Proverbs 28 29 30 31 Psalm 29 Psalm 30 Psalm 59 Psalm 60 Psalm 89 Psalm 90 Psalm 119 Psalm 120 Psalm 149 Psalm 150 Proverbs 29 Proverbs 30 Proverbs 31.