Exploring the Use of Communication and Information Technologies by Older Adults

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Project Folder: Honour Without Courage

Project by Levi Orta Montreal, 2013 In Quebec, 85% of the population rejects the monarchy as a model of representation for Canada; the monarchy justifies itself as a cultural tradition of the country. I am interested in linking the concepts of “representation” in art and “representation” in politics, triggering a perversion of both. The project uses a fictional event where I save the life of a woman disguised as Queen Elizabeth II in order to apply for the “Star of Courage”, a decoration awarded by the representative of the monarchy in Canada by order of the Queen. The whole application process, the proofs of the heroic action, and the expected granting of the medal are part of the project. It is one representation that meets another, the realities of art and politics dissolving into each other and becoming accomplices. … Au Québec, 85% de la population rejette la monarchie comme modèle de représentation du Canada ; la monarchie justifie l’implémentation de ses pratiques comme un sujet de tradition culturelle du pays. Je suis intéressé à lier les concepts de « représentation » dans l’art et de « représentation » dans la politique, afin de provoquer une perversion de ces représentations. Le projet consiste à utiliser un incident fictif lors duquel je sauve la vie d'une femme déguisée en Reine Elizabeth II afin de soumettre ma candidature à la nomination de la « Star of Courage », une décoration décernée par la monarchie canadienne sur ordre de la Reine. Tout le processus d’application, les preuves de l’action héroïque ainsi que l’octroi tant attendu de la médaille font partie du projet. -

Canada's New Governor General

CANADA’S NEW GOVERNOR GENERAL Introduction The governor general is the Queen’s the governor general is that he or she Focus representative in Canada. The position remains impartial; that means that he or David Johnston was appointed the 28th exists because of Canada’s history as she cannot take sides with a particular Governor General of a British colony. Even though Canada political party when offering advice. Canada on October 1, is no longer a colony of Britain, a The process of selecting David 2010. While Johnston number of symbolic traditions, laws, and Johnston as Canada’s newest governor is widely regarded institutions established as a result of this general began when Prime Minister as a solid choice to former relationship still exist. Typically Stephen Harper established a non- act as the Queen’s every five years, the prime minister partisan panel composed of six people representative in Canada, he must nominates a new governor general. to provide a shortlist of candidates. follow in the footsteps The position of the governor general is They canvassed more than 200 people of Michaëlle Jean, largely a ceremonial one. The governor for suggestions. Those canvassed a well-admired and general doesn’t vote in Parliament included premiers, civic leaders, former gracious woman who or introduce bills. But he or she has prime ministers, and opposition leaders was thrust into a the power to “advise, encourage, and Michael Ignatieff and Jack Layton. It constitutional crisis to warn” the prime minister and the was from their shortlist that Harper during her tenure as Governor General. -

ON TRACK Autonome Et Renseigné

Independent and Informed ON TRACK Autonome et renseigné The Conference of Defence Associations Institute ● L’Institut de la Conférence des Associations de la Défense Winter / Hiver Volume 15, Number 4 2010/2011 The Vimy Award Recipient Sustaining Funding for Defence No Mountain Too High China in the Arctic What next for the Canadian Forces? DND Photo / Photo DDN CDA INSTITUTE BOARD OF DIRECTORS Admiral (Ret’d) John Anderson Général (Ret) Maurice Baril Dr. David Bercuson L’hon. Jean-Jacques Blais Dr. Douglas Bland Mr. Robert T. Booth Mr. Thomas Caldwell Mr. Mel Cappe Dr. Jim Carruthers Mr. Paul H. Chapin Mr. Terry Colfer Dr. John Scott Cowan Mr. Dan Donovan Lieutenant-général (Ret) Richard Evraire Honourary Lieutenant-Colonel Justin Fogarty Mr. Robert Fowler Colonel, The Hon. John Fraser Lieutenant-général (Ret) Michel Gauthier Rear-Admiral (Ret’d) Roger Girouard Brigadier-General (Ret’d) Bernd A. Goetze Honourary Colonel Blake C. Goldring Mr. Mike Greenley Général (Ret) Raymond Henault Honourary Colonel, Dr. Frederick Jackman The Hon. Colin Kenny Dr. George A. Lampropoulos Colonel (Ret’d) Brian MacDonald Major-General (Ret’d) Lewis MacKenzie Brigadier-General (Ret’d) W. Don Macnamara Lieutenant-général (Ret) Michel Maisonneuve General (Ret’d) Paul D. Manson Mr. John Noble The Hon. David Pratt Honourary Captain (N) Colin Robertson The Hon. Hugh Segal Colonel (Ret’d) Ben Shapiro Brigadier-General (Ret’d) Joe Sharpe M. André Sincennes Dr. Joel Sokolsky Rear-Admiral (Ret’d) Ken Summers The Hon. Pamela Wallin ON TRACK VOLUME 15 NUMBER 4 CONTENTS CONTENU WINTER / HIVER 2010/11 PRESIDENT / PRÉSIDENT Dr. John Scott Cowan, BSc, MSc, PhD From the Executive Director......................................................................4 VICE PRESIDENT / VICE PRÉSIDENT Général (Ret’d) Raymond Henault, CMM, CD Colonel (Ret’d) Alain Pellerin Le mot du Directeur exécutif....................................................................4 EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR / DIRECTEUR EXÉCUTIF Le Colonel (Ret) Alain Pellerin Colonel (Ret) Alain M. -

BROCK's BANTER: Above the Footsteps of Giants

This page was exported from - The Auroran Export date: Fri Oct 1 4:52:17 2021 / +0000 GMT BROCK'S BANTER: Above the footsteps of giants By Brock Weir It is sometimes said our leaders lack perspective, whether it is looking at the elusive, oft-mentioned ? and usually undefined ? ?big picture? or having a full grasp of Canada's (or Ontario's, or insert the jurisdiction of your choice) place in the world. Well, as far as our next Governor General is concerned, we can throw those ideas out the window. I think the Queen would be hard-pressed to find someone in the country with a wider-ranging perspective of the world, as well as the issues within it, than the newly-minted Governor General-Designate Julie Payette, the former Chief Astronaut of the Canadian Space Agency. A systems engineer by trade, she brings an impressive résumé to Rideau Hall, ranging from a long-time position at IBM to Board positions at organization as varied as Queen's University, Drug Free Kids Canada, the International Olympic Committee Women in Sports Commission, and the Montreal Bach Festival. There are few people who can say this is not a well-rounded portfolio! Ms. Payette's appointment as Governor General-Designate was announced by Prime Minister Justin Trudeau in Ottawa last week, following a meeting with the Queen in Edinburgh. ?She is already well-known to Canadians,? said Trudeau, noting her achievement of being the second Canadian woman in space following Roberta Bondar. ?Ms. Payette's life has been one dedicated to discovery, to dreaming big, to always staying focused on the things that matter most. -

By Their Excellencies the Right Honourable David Johnston, Governor General of Canada and Mrs

State Visit to the Kingdom of Sweden, by Their Excellencies the Right Honourable David Johnston, Governor General of Canada and Mrs. Sharon Johnston Delegation State Visit to the Kingdom of Sweden February 19-23, 2017 Official Delegation State Visit to the Kingdom of Sweden February 19-23, 2017 HIS EXCELLENCY THE RIGHT HONOURABLE DAVID JOHNSTON Governor General of Canada David Johnston was born in Copper Cliff, near Sudbury, Ontario on June 28, 1941, the son of Dorothy Stonehouse and Lloyd Johnston, the retail manager of a local hardware store. Following the family’s move to Sault Ste. Marie, he attended Sault Collegiate Institute and played under-17 hockey with future hockey hall of famers Phil and Tony Esposito. Mr. Johnston went on to attend Harvard University, where he earned a Bachelor of Arts degree in 1963, twice being selected to the All-American hockey team on his way to being named to Harvard’s athletic hall of fame. He later obtained Bachelor of Laws degrees from the University of Cambridge and Queen’s University. In 1964, he married his high school sweetheart, Sharon Johnston, with whom he has five daughters. They are grandparents to 14 grandchildren. Mr. Johnston’s professional career began in 1966 as assistant professor in the Queen’s University law faculty. He moved on to the University of Toronto’s law faculty in 1968, and became dean of Western University’s law faculty in 1974. He was named principal and vice-chancellor of McGill University in 1979, serving for fifteen years before returning to teaching as a full-time professor in the McGill Faculty of Law. -

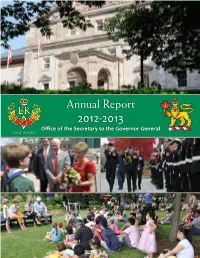

Annual Report

Annual Report 2012-2013 Office of the Secretary to the Governor General VIVAT REGINA Emblem for the Diamond Jubilee of Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II This emblem was created to mark the 2012 celebrations of the Diamond Jubilee, the 60th anniversary, of Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II’s accession to the Throne as Queen of Canada. The anniversary is expressed by the central diamond shape. The Royal Cypher consists of the Royal Crown above the letters EIIR (i.e., Elizabeth II Regina, the latter word meaning Queen in Latin). The maple leaves refer to Canada, while the motto VIVAT REGINA means “Long live The Queen!” VIVAT REGINA The Viceregal Lion The emblem used by the Office of the Secretary to the Governor General is the crest from the Royal Arms of Canada. It consists of a gold lion wearing the Royal Crown and holding in its right paw a red maple leaf. The lion stands on a wreath of the official colours of Canada, red and white. Photo credits Canadian Space Agency: page 15 Sgt Eric Jolin, Rideau Hall: pg. 17 MCpl Vincent Carbonneau, Rideau Hall: pgs. 9, 13 Pte Ariane Montambeault, Rideau Hall: cover page, pgs. 6, 14 Department of Canadian Heritage: page 5 Cpl Roxanne Shewchuk, Rideau Hall: pgs. 5, 8, 10, 11, 13, 15, 17 Sgt Ronald Duchesne, Rideau Hall: cover page, pgs. 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12, 14, 15 Chris Weicker, Rideau Hall: pgs. 16, 18 Sgt Serge Gouin, Rideau Hall: pgs. 16, 18 MCpl Dany Veillette, Rideau Hall: pgs. 5, 6, 8, 9, 10, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16 MCpl Evan Kuelz, Rideau Hall: page 3 Rideau Hall, 1 Sussex Drive, Ottawa, Ontario K1A 0A1 Citadelle of Québec, 1 Côte de la Citadelle, Québec, Quebec G1R 4V7 © Her Majesty The Queen in Right of Canada represented by the Office of the Secretary to the Governor General (2013). -

Canada and the Crown: Essays in Constitutional Monarchy Edited by D

New title from Queen’s School of Policy Studies Series McGill-Queen’s University Press www.queensu.ca/sps/ Canada and the Crown: Essays in Constitutional Monarchy Edited by D. Michael Jackson and Philippe Lagassé Foreword by His Excellency the Right Honourable David Johnston Governor General of Canada Stephen Harper's Conservative government has reversed the trend of its predecessors by giving the Crown a higher profile through royal tours, publications, and symbolic initiatives. Based on papers given at a Diamond Jubilee conference on the Crown held in Regina in 2012, Canada and the Crown assesses the historical and contemporary importance of constitutional monarchy in Canada. Established and emerging scholars consider the Canadian Crown from a variety of viewpoints, including the ways in which the monarch relates to Quebec, First Nations, the media, educa- tion, Parliament, the constitution, and the military. They also consider a republican option for Canada. Editors D. Michael Jackson and Philippe Lagassé provide context for the essays, summarize and expand on the issues discussed by the contributors, and offer a perspective on further study of the Crown in Canada. January 2013 Queen’s Policy Studies Series – Institute of Intergovernmental Relations ISBN 978-1-55339-204-0 $39.95 paper 6 x 9 336 pp Contributors include Richard Berthelsen, Lieutenant-Colonel Alexander Bolt (Office of the Judge Advocate General), James W.J. Bowden, Stephanie Danyluk (Whitecap-Dakota First Nation), Linda Cardinal (University of Ottawa), Phillip Crawley (CEO, The Globe and Mail), John Fraser (Massey College), Carolyn Harris (University of Toronto), Robert E. Hawkins (University of Regina), Ian Holloway (University of Calgary), Senator Serge Joyal, Nicholas A. -

Alumni Newsletter Recruitment Edition

Spring 2013 Alumni Newsletter Recruitment Edition Foundation for Educational Exchange Between Canada and the United States of America Fulbright Canada Award for Outstanding Public Service On May 28, 2013, His Excellency the Right Honourable David Johnston, Governor General of Canada, received the inaugural A message from Fulbright Canada Award for Outstanding CEO Michael Hawes Public Service at a special ceremony in the Library Room at the Faculty Club at Harvard Spring is always an exciting time, University. A discussion amongst Fulbright with current Fulbrighters returning Scholars followed the award ceremony. home from their transformational experiences and new grantees The Governor General was announced as readying themselves for their the inaugural recipient of the award at a upcoming adventure. Please check celebration in Calgary on May 1st. The Mr. Brian McKenzie, Governor General Johnston, our website in the coming weeks Dr. Catherine Kreatsoulas, and Dr. Michael Hawes. event at Harvard provided a platform for the (from left to right) for the complete list of our 2013- Governor General to accept the Fulbright 2014 grantees and their projects. Canada Award in person and to engage with to John Devlin, an Alberta lawyer whose Canadian Fulbright scholars, as well as other aspirations reflect the deeds of Governor For Fulbright Canada, the Spring students and academics in the area. General Johnston. Devlin, a graduate of 2013 will be remembered as of the University of Alberta Law School the time that we announced the and the University of Calgary, will use “His Excellency has promoted new ideas, inaugural recipient of the Fulbright the scholarship to pursue a LLM in encouraged open discussion, supported Canada Award for Outstanding Constitutional Law at Harvard University. -

Monarchist League of Canada

THE MONARCHIST LEAGUE of CANADA Justin Trudeau takes Oath of Office as Prime Minister before Governor General David Johnston. “I do swear that I will be faithful and bear true allegiance to Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth the Second, Queen of Canada, Her Heirs and Successors. So help me God.” – Canada’s Oath of Allegiance, sworn by many public officials Members of the Canadian Royal Family make frequent homecomings here. In May 2016, Prime Minister Trudeau joined Prince Harry in checking out facilities for the Toronto 2017 Invictus Games, Prince Harry’s sporting event for ill, injured and wounded soldiers and veterans. Our Canadian Monarchy © 2017 by the Monarchist League of Canada. All rights reserved. All images remain the property of their respective owners 2 OUR CANADIAN MONARCHY Canada 150 portrait of The Queen, wearing the Maple Leaf brooch presented to her mother by George VI before their 1939 tour of Canada. Elizabeth II, Queen of Canada The Queen is the representation of all of Canada within one person. Together with her representatives and members of the Royal Family, she promotes “all that is best and most admired in the Canadian ideal”. Governor General Julie Payette gives Royal Assent in the Senate on December 12, 2017. 3 THE MONARCHIST LEAGUE of CANADA Canada: always a monarchy he lands that now comprise modern-day Canada Thave long been reigned over by hereditary leaders. Canada enjoys a history of functioning government that began to evolve centuries before European contact with Indigenous peoples. Many Indigenous groups were headed by a chieftain who was advised by a council of elders, not unlike the series of French and British monarchs in whose name the original colonies of North America were founded. -

Lecture Series

BB RR OO CC KK VV II LL LL EE MM UU SS EE UU MM LLeecctt1uu7 t hrr A n neeu a l SSW i n eet e r rriieess TUESDAYS @ 10AM | FEBRUARY 4 - MARCH 3 | Brockville Museum February 4th : Dr. Erika Behrisch Elce, Royal Military College Lady Franklin and the Franklin Expedition In the 1850s, the search for the lost Franklin Expedition was considered England’s “Modern Odyssey,” and Lady Franklin nothing less than the “Penelope of England.” Today, she is still often portrayed as a symbol, but now also as a conniving strategist whose own ambition propelled her husband to his tragic end. This presentation considers the life of one of the Victorian period’s most compelling women in a new light: not as Penelope or conniver, but as a master of narrative. February 11th: J. William (Bill) Galbraith, author From "The 39 Steps" to the Steps of Rideau Hall John Buchan, best known as the Scottish-born author of spy thrillers, was appointed Governor General of Canada in 1935, an appointment that created a nation-wide controversy but which ended by inspiring several of his Canadian successors, including Adrienne Clarkson and David Johnston. February 18th: Dan Black, author Veil of Secrecy Canada and the CPR participated in a secret scheme to transport tens of thousands of Chinese labourers to France during the First World War. February 25th: Dr. Steven High, Concordia University Donald Trump and the Rust Belt 5: The Populist Politics of De-industrialization Many small towns all over North America have been struggling as factories that helped build the town close their doors. -

His Excellency the Right Honourable David Johnston Governor General of Canada

His Excellency the Right Honourable David Johnston Governor General of Canada David Johnston began his professional career as an assistant professor in the Faculty of Law at Queen’s University in 1966, moving to the Law Faculty at the University of Toronto in 1968. He became dean of the Faculty of Law at the University of Western Ontario in 1974. In 1979, he was named principal and vice-chancellor of McGill University, and in July 1994, he returned to the McGill Faculty of Law as a full-time professor. In June 1999, he became the fifth president of the University of Waterloo. Mr. Johnston has served on many provincial and federal task forces and committees. He has also served on the boards of a number of companies, including Arise, CGI, Fairfax and Masco. He was president of the Association of Universities and Colleges of Canada, and of the Conférence des recteurs et des principaux des universités du Québec. He was the founding chair of the National Round Table on the Environment and the Economy, chaired the federal government’s Information Highway Advisory Council, and served as the first non- American chair of the Board of Overseers at Harvard University. He is the author or co-author of two dozen books, holds honorary doctorates from over a dozen universities, and has been awarded the Order of Canada (Companion). Mr. Johnston holds an LL.B. from Queen’s University (1966), an LL.B. from the University of Cambridge (1965), and an AB from Harvard University (1963). While at Harvard, he was twice selected for the All-American hockey team and is a member of Harvard’s Athletic Hall of Fame. -

Annual Report: 2013-2014

Annual Report 2013-2014 Office of the Secretary to the Governor General September 26, 2014 25 Years The Canadian Heraldic Authority The Viceregal Lion The emblem used by the Office of the Secretary to the Governor General is the crest from the Royal Arms of Canada. It consists of a gold lion wearing the Royal Crown and holding in its right paw a red maple leaf. The lion stands on a wreath of the official colours of Canada, red and white. The Shield of the Canadian Heraldic Authority The shield features the maple leaf of Canada charged with a smaller shield, which indicates the heraldic responsibilities of the Canadian Heraldic Authority. June 2013 marked the 25th anniversary of the Authority, established in 1988, as part of the Office of the Secretary to the Governor General. Photo credits Canada Post: page 7 François Grenier, Traveling Exhibit: page 10 MCpl Vincent Carbonneau, Rideau Hall: pgs. 3, 5, 7, 8, 13, 15, 17, 18 Sgt Eric Jolin, Rideau Hall: page 17 WO Kevin Daly: page 16 MCpl Jean-François Néron, Rideau Hall: page 9 Department of Canadian Heritage: page 5 Cpl Carbe Orellana, Rideau Hall: page 5 Sgt Ronald Duchesne, Rideau Hall: Cover Page, pgs. 4, 5, 6, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, Cpl Roxanne Shewchuk, Rideau Hall: Cover Page, pgs. 5, 6, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 14, 15 14, 15 Sgt Serge Gouin, Rideau Hall: page 16 Rideau Hall, 1 Sussex Drive, Ottawa, Ontario K1A 0A1 Citadelle of Québec, 1 Côte de la Citadelle, Québec, Quebec G1R 4V7 © Her Majesty The Queen in Right of Canada represented by the Office of the Secretary to the Governor General (2014).