Dogs, Meat and Douglas Mawson

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Introduction Itinerary

ANTARCTICA - AKADEMIK SHOKALSKY TRIP CODE ACHEIWM DEPARTURE 10/02/2022 DURATION 25 Days LOCATIONS East Antarctica INTRODUCTION This is a 25 day expedition voyage to East Antarctica starting and ending in Invercargill, New Zealand. The journey will explore the rugged landscape and wildlife-rich Subantarctic Islands and cross the Antarctic circle into Mawsonâs Antarctica. Conditions depending, it will hope to visit Cape Denison, the location of Mawsonâs Hut. East Antarctica is one of the most remote and least frequented stretches of coast in the world and was the fascination of Australian Antarctic explorer, Sir Douglas Mawson. A true Australian hero, Douglas Mawson's initial interest in Antarctica was scientific. Whilst others were racing for polar records, Mawson was studying Antarctica and leading the charge on claiming a large chunk of the continent for Australia. On his quest Mawson, along with Xavier Mertz and Belgrave Ninnis, set out to explore and study east of the Mawson's Hut. On what began as a journey of discovery and science ended in Mertz and Ninnis perishing and Mawson surviving extreme conditions against all odds, with next to no food or supplies in the bitter cold of Antarctica. This expedition allows you to embrace your inner explorer to the backdrop of incredible scenery such as glaciers, icebergs and rare fauna while looking out for myriad whale, seal and penguin species. A truly unique journey not to be missed. ITINERARY DAY 1: Invercargill Arrive at Invercargill, New Zealand’s southernmost city. Established by Scottish settlers, the area’s wealth of rich farmland is well suited to the sheep and dairy farms that dot the landscape. -

A Sheffield Hallam University Thesis

The polar sublime in contemporary poetry of Arctic and Antarctic exploration. JACKSON, Andrew Buchanan. Available from the Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive (SHURA) at: http://shura.shu.ac.uk/20170/ A Sheffield Hallam University thesis This thesis is protected by copyright which belongs to the author. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. Please visit http://shura.shu.ac.uk/20170/ and http://shura.shu.ac.uk/information.html for further details about copyright and re-use permissions. jj Learning and information Services I Adsetts Centre, City Campus * Sheffield S1 1WD 102 156 549 0 REFERENCE ProQuest Number: 10700005 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10700005 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 The Polar Sublime in Contemporary Poetry of Arctic and Antarctic Exploration Andrew Buchanan Jackson A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of Sheffield Hallam University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy September 2015 Abstract In this thesis I formulate the concept of a polar sublime, building on the work of Chauncy Loomis and Francis Spufford, and use this new framework for the appraisal of contemporary polar-themed poetry. -

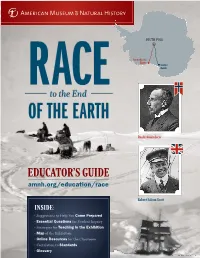

Educator's Guide

SOUTH POLE Amundsen’s Route Scott’s Route Roald Amundsen EDUCATOR’S GUIDE amnh.org/education/race Robert Falcon Scott INSIDE: • Suggestions to Help You Come Prepared • Essential Questions for Student Inquiry • Strategies for Teaching in the Exhibition • Map of the Exhibition • Online Resources for the Classroom • Correlation to Standards • Glossary ESSENTIAL QUESTIONS Who would be fi rst to set foot at the South Pole, Norwegian explorer Roald Amundsen or British Naval offi cer Robert Falcon Scott? Tracing their heroic journeys, this exhibition portrays the harsh environment and scientifi c importance of the last continent to be explored. Use the Essential Questions below to connect the exhibition’s themes to your curriculum. What do explorers need to survive during What is Antarctica? Antarctica is Earth’s southernmost continent. About the size of the polar expeditions? United States and Mexico combined, it’s almost entirely covered Exploring Antarc- by a thick ice sheet that gives it the highest average elevation of tica involved great any continent. This ice sheet contains 90% of the world’s land ice, danger and un- which represents 70% of its fresh water. Antarctica is the coldest imaginable physical place on Earth, and an encircling polar ocean current keeps it hardship. Hazards that way. Winds blowing out of the continent’s core can reach included snow over 320 kilometers per hour (200 mph), making it the windiest. blindness, malnu- Since most of Antarctica receives no precipitation at all, it’s also trition, frostbite, the driest place on Earth. Its landforms include high plateaus and crevasses, and active volcanoes. -

S. Antarctic Projects Officer Bullet

S. ANTARCTIC PROJECTS OFFICER BULLET VOLUME III NUMBER 8 APRIL 1962 Instructions given by the Lords Commissioners of the Admiralty ti James Clark Ross, Esquire, Captain of HMS EREBUS, 14 September 1839, in J. C. Ross, A Voya ge of Dis- covery_and Research in the Southern and Antarctic Regions, . I, pp. xxiv-xxv: In the following summer, your provisions having been completed and your crews refreshed, you will proceed direct to the southward, in order to determine the position of the magnet- ic pole, and oven to attain to it if pssble, which it is hoped will be one of the remarka- ble and creditable results of this expedition. In the execution, however, of this arduous part of the service entrusted to your enter- prise and to your resources, you are to use your best endoavours to withdraw from the high latitudes in time to prevent the ships being besot with the ice Volume III, No. 8 April 1962 CONTENTS South Magnetic Pole 1 University of Miohigan Glaoiologioal Work on the Ross Ice Shelf, 1961-62 9 by Charles W. M. Swithinbank 2 Little America - Byrd Traverse, by Major Wilbur E. Martin, USA 6 Air Development Squadron SIX, Navy Unit Commendation 16 Geological Reoonnaissanoe of the Ellsworth Mountains, by Paul G. Schmidt 17 Hydrographio Offices Shipboard Marine Geophysical Program, by Alan Ballard and James Q. Tierney 21 Sentinel flange Mapped 23 Antarctic Chronology, 1961-62 24 The Bulletin is pleased to present four firsthand accounts of activities in the Antarctic during the recent season. The Illustration accompanying Major Martins log is an official U.S. -

Antarctica: Music, Sounds and Cultural Connections

Antarctica Music, sounds and cultural connections Antarctica Music, sounds and cultural connections Edited by Bernadette Hince, Rupert Summerson and Arnan Wiesel Published by ANU Press The Australian National University Acton ACT 2601, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at http://press.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Title: Antarctica - music, sounds and cultural connections / edited by Bernadette Hince, Rupert Summerson, Arnan Wiesel. ISBN: 9781925022285 (paperback) 9781925022292 (ebook) Subjects: Australasian Antarctic Expedition (1911-1914)--Centennial celebrations, etc. Music festivals--Australian Capital Territory--Canberra. Antarctica--Discovery and exploration--Australian--Congresses. Antarctica--Songs and music--Congresses. Other Creators/Contributors: Hince, B. (Bernadette), editor. Summerson, Rupert, editor. Wiesel, Arnan, editor. Australian National University School of Music. Antarctica - music, sounds and cultural connections (2011 : Australian National University). Dewey Number: 780.789471 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design and layout by ANU Press Cover photo: Moonrise over Fram Bank, Antarctica. Photographer: Steve Nicol © Printed by Griffin Press This edition © 2015 ANU Press Contents Preface: Music and Antarctica . ix Arnan Wiesel Introduction: Listening to Antarctica . 1 Tom Griffiths Mawson’s musings and Morse code: Antarctic silence at the end of the ‘Heroic Era’, and how it was lost . 15 Mark Pharaoh Thulia: a Tale of the Antarctic (1843): The earliest Antarctic poem and its musical setting . 23 Elizabeth Truswell Nankyoku no kyoku: The cultural life of the Shirase Antarctic Expedition 1910–12 . -

Leadership Lessons from Sir Douglas Mawson

LEADERSHIP LESSONS FROM SIR DOUGLAS MAWSON Sir Douglas Mawson was one of the most courageous and adventurous men Australia has produced. Through his determination and efforts he added to the Commonwealth an area in Antarctica almost as large as Australia itself. He was born in Yorkshire, England May 1882 and at the age of four his parents migrated to Sydney. He was educated at the University of Sydney and played a leading role in founding the Science Society. His great interest was geology and in 1902 he joined expeditions to survey the land around Mittagong and later the New Hebrides Islands. In 1905 he was appointed Lecturer in Mineralogy and Petrology at the University of Adelaide which he served in various capacities until his death. In 1907 a tour of the Snowy Mountains became his first experience of a glacial environment with an ascent of Mount Kosciusko and the beginning of his interest in Antarctica. At this time Britain, Germany and Sweden were involved in Antarctica, Ernest Shackleton was determined to reach the South Pole and in 1907 lead a party with Mawson joining as physicist and surveyor of the expedition. They reached the continent in February 1908 and Shackleton decided that Mawson, Professor Edgeworth David and Dr Forbes MacKay should travel 1800km to the Magnetic Pole. During the expedition they met very bad surfaces and some blizzards and they had underestimated the distance to the Magnetic Pole. While they reached their destination all were in poor condition with only seal meat to eat. They struggled back over hundreds of kilometres of ice caps and at last saw their ship, the Nimrod, less than a kilometre away when suddenly Mawson fell six metres down a crevasse. -

MS ROALD AMUNDSEN Voyage Handbook

MS ROALD AMUNDSEN voyage handbook MS ROALD AMUNDSEN VOYAGE HANDBOOK 20192020 1 Dear Adventurer 2 Dear adventurer, Europe 4 Congratulations on booking make your voyage even more an extraordinary cruise on enjoyable. Norway 6 board our extraordinary new vessel, MS Roald Amundsen. This handbook includes in- formation on your chosen Svalbard 8 The ship’s namesake, Norwe- destination, as well as other gian explorer Roald Amund- destinations this ship visits Greenland 12 sen’s success as an explorer is during the 2019-2020 sailing often explained by his thor- season. We hope you will nd The Northwest Passage 16 ough preparations before this information inspiring. departure. He once said “vic- Contents tory awaits him who has every- We promise you an amazing Alaska 18 thing in order.” Being true to adventure! Amund sen’s heritage of good South America 20 planning, we encourage you to Welcome aboard for the ad- read this handbook. venture of a lifetime! Antarctica 24 It will provide you with good Your Hurtigruten Team Protecting the Antarctic advice, historical context, Environment from Invasive 28 practical information, and in- Species spiring information that will Environmental Commitment 30 Important Information 32 Frequently Asked Questions 33 Practical Information 34 Before and After Your Voyage Life on Board 38 MS Roald Amundsen Pack Like an Explorer 44 Our Team on Board 46 Landing by Small Boats 48 Important Phone Numbers 49 Maritime Expressions 49 MS Roald Amundsen 50 Deck Plan 2 3 COVER FRONT PHOTO: © HURTIGRUTEN © GREGORY SMITH HURTIGRUTEN SMITH GREGORY © COVER BACK PHOTO: © ESPEN MILLS HURTIGRUTEN CLIMATE Europe lies mainly lands and new trading routes. -

Meet... Douglas Mawson

TEACHERS’ RESOURCES RECOMMENDED FOR Lower and upper primary CONTENTS 1. Plot summary 1 2. About the author 2 3. About the illustrator 2 4. Interview with the author 2 5. Pre-reading questions 2 6. Key study topics 3 7. Other books in this series 4 8. Worksheets 5 KEY CURRICULUM AREAS Learning areas: History, English, Literacy THEMES Australian History Exploration Antarctica PREPARED BY Meet Douglas Mawson Penguin Random House Australia PUBLICATION DETAILS Written by Mike Dumbleton ISBN: 9780857981950 (hardback) Illustrated by Snip Green ISBN: 9780857981974 (ebook) ISBN: 9780857981967 (paperback) These notes may be reproduced free of charge for use and study within schools but they may not be PLOT SUMMARY reproduced (either in whole or in part) and offered for commercial sale. The year 2014 marks the 100th anniversary of the first Australian Antarctic Expedition (1911–14), led Visit penguin.com.au/teachers to find out how our fantastic Penguin Random House Australia books by Douglas Mawson. can be used in the classroom, sign up to the teachers’ newsletter and follow us on In this book, we follow Mawson and his team on @penguinteachers. their journey to Antarctica, as well as on their dangerous and challenging trek across the frozen Copyright © Penguin Random House Australia continent as they attempt to gather scientific and 2014 geological information. Meet Douglas Mawson Mike Dumbleton & Snip Green ABOUT THE AUTHOR 4. What was the most challenging part of the project? Mike Dumbleton is a writer with many educational It was a challenge to tell the story in a way that and children’s books to his credit. -

Cape Denison MAWSON CENTENNIAL 1911–2011, Commonwealth Bay

Cape Denison MAWSON CENTENNIAL 1911–2011, Commonwealth Bay Mawson and the Australasian Geology of Cape Denison Landforms of Cape Denison Position of Cape Denison in Gondwana Antarctic Expedition The two dominant rock-types found at Cape Denison Cape Denison is a small ice-free rocky outcrop covering Around 270 Million years ago the continents that we are orthogneiss and amphibolite. There are also minor less than one square kilometre, which emerges from The Australasian Antarctic Expedition (AAE) took place know today were part of a single ancient supercontinent occurrences of coarse grained felsic pegmatites. beneath the continental ice sheet. Stillwell (1918) reported between 1911 and 1914, and was organised and led by called Pangea. Later, Pangea split into two smaller that the continental ice sheet rises steeply behind Cape the geologist, Dr Douglas Mawson. The expedition was The Cape Denison Orthogneiss was described by Stillwell (1918) as supercontinents, Laurasia and Gondwana, and Denison reaching an altitude of ‘1000 ft in three miles and jointly funded by the Australian and British Governments coarse-grained grey quartz-feldspar layered granitic gneiss. These rock Antarctica formed part of Gondwana. with contributions received from various individuals and types are normally formed by metamorphism (changed by extreme heat 1500 ft in five and a half miles’ (approximately 300 metres and pressure) of granites. The Cape Denison Orthogneiss is found around In current reconstructions of the supercontinent Gondwana, the Cape scientific societies, including the Australasian Association to 450 metres over 8.9 kilometres). Photography by Chris Carson Cape Denison, the nearby offshore Mackellar Islands, and nearby outcrops Denison–Commonwealth Bay region was located adjacent to the coast for the Advancement of Science. -

The Harrowing Story of Shackletons Ross Sea Party Pdf Free Download

THE LOST MEN: THE HARROWING STORY OF SHACKLETONS ROSS SEA PARTY PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Kelly Tyler-Lewis | 384 pages | 03 Sep 2007 | Bloomsbury Publishing PLC | 9780747579724 | English | London, United Kingdom Ross Sea party - Wikipedia Aurora finally broke free from the ice on 12 February and managed to reach New Zealand on 2 April. Because Mackintosh had intended to use Aurora as the party's main living quarters, most of the shore party's personal gear, food, equipment and fuel was still aboard when the ship departed. Although the sledging rations intended for Shackleton's depots had been landed, [41] the ten stranded men were left with "only the clothes on their backs". We cannot expect rescue before then, and so we must conserve and economize on what we have, and we must seek and apply what substitutes we can gather". On the last day of August Mackintosh recorded in his diary the work that had been completed during the winter, and ended: "Tomorrow we start for Hut Point". The second season's work was planned in three stages. Nine men in teams of three would undertake the sledging work. The first stage, hauling over the sea ice to Hut Point, started on 1 September , and was completed without mishap by the end of the month. Shortly after the main march to Mount Hope began, on 1 January , the failure of a Primus stove led to three men Cope, Jack and Gaze returning to Cape Evans, [49] where they joined Stevens. The scientist had remained at the base to take weather measurements and watch for the ship. -

Roald Amundsen - First Man to Reach Both North and South Poles

Roald Amundsen - first man to reach both North and South Poles Roald Amundsen (1872-1928) was born to a shipowning family near Fredrikstad, Norway on July 16, 1872. From an early age, he was fascinated with polar exploration. He joined the Belgian Antarctic Expedition of 1897, serving as first mate on the ship Belgica. When the ship was beset in the ice off the Antarctic Peninsula, its crew became the first to spend a winter in the Antarctic. First person to transit the Northwest Passage In 1903, he led a seven-man crew on the small steel-hull sealing vessel Gjoa in an attempt to traverse the fabled Northwest Passage. They entered Baffin Bay and headed west. The vessel spent two winters off King William Island (at a location now called Gjoa Haven). After a third winter trapped in the ice, Amundsen was able to navigate a passage into the Beaufort Sea after which he cleared into the Bering Strait, thus having successfully navigated the Northwest Passage. Continuing to the south of Victoria Island, the ship cleared the Canadian Arctic Archipelago on 17 August 1905, but had to stop for the winter before going on to Nome on the Alaska District's Pacific coast.before arriving in Nome, Alaska in 1906. It was at this time that Amundsen received news that Norway had formally become independent of Sweden and had a new king. Amundsen sent the new King Haakon VII news that it "was a great achievement for Norway". He said he hoped to do more and signed it "Your loyal subject, Roald Amundsen. -

Australian Antarctic Magazine

AusTRALIAN MAGAZINE ISSUE 23 2012 7317 AusTRALIAN ANTARCTIC ISSUE 2012 MAGAZINE 23 The Australian Antarctic Division, a Division of the Department for Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities, leads Australia’s CONTENTS Antarctic program and seeks to advance Australia’s Antarctic interests in pursuit of its vision of having PROFILE ‘Antarctica valued, protected and understood’. It does Charting the seas of science 1 this by managing Australian government activity in Antarctica, providing transport and logistic support to SEA ICE VOYAGE Australia’s Antarctic research program, maintaining four Antarctic science in the spring sea ice zone 4 permanent Australian research stations, and conducting scientific research programs both on land and in the Sea ice sky-lab 5 Southern Ocean. Search for sea ice algae reveals hidden Antarctic icescape 6 Australia’s four Antarctic goals are: Twenty metres under the sea ice 8 • To maintain the Antarctic Treaty System and enhance Australia’s influence in it; Pumping krill into research 9 • To protect the Antarctic environment; Rhythm of Antarctic life 10 • To understand the role of Antarctica in the global SCIENCE climate system; and A brave new world as Macquarie Island moves towards recovery 12 • To undertake scientific work of practical, economic and national significance. Listening to the blues 14 Australian Antarctic Magazine seeks to inform the Bugs, soils and rocks in the Prince Charles Mountains 16 Australian and international Antarctic community Antarctic bottom water disappearing 18 about the activities of the Australian Antarctic Antarctic bioregions enhance conservation planning 19 program. Opinions expressed in Australian Antarctic Magazine do not necessarily represent the position of Antarctic ice clouds 20 the Australian Government.