Hugh Chilton

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Evangelicalism and the Church of England in the Twentieth Century

STUDIES IN MODERN BRITISH RELIGIOUS HISTORY Volume 31 EVANGELICALISM AND THE CHURCH OF ENGLAND IN THE TWENTIETH CENTURY REFORM, RESISTANCE AND RENEWAL Evangelicalism and the Church.indb 1 25/07/2014 10:00 STUDIES IN MODERN BRITISH RELIGIOUS HISTORY ISSN: 1464-6625 General editors Stephen Taylor – Durham University Arthur Burns – King’s College London Kenneth Fincham – University of Kent This series aims to differentiate ‘religious history’ from the narrow confines of church history, investigating not only the social and cultural history of reli- gion, but also theological, political and institutional themes, while remaining sensitive to the wider historical context; it thus advances an understanding of the importance of religion for the history of modern Britain, covering all periods of British history since the Reformation. Previously published volumes in this series are listed at the back of this volume. Evangelicalism and the Church.indb 2 25/07/2014 10:00 EVANGELICALISM AND THE CHURCH OF ENGLAND IN THE TWENTIETH CENTURY REFORM, RESISTANCE AND RENEWAL EDITED BY ANDREW ATHERSTONE AND JOHN MAIDEN THE BOYDELL PRESS Evangelicalism and the Church.indb 3 25/07/2014 10:00 © Contributors 2014 All Rights Reserved. Except as permitted under current legislation no part of this work may be photocopied, stored in a retrieval system, published, performed in public, adapted, broadcast, transmitted, recorded or reproduced in any form or by any means, without the prior permission of the copyright owner First published 2014 The Boydell Press, Woodbridge ISBN 978-1-84383-911-8 The Boydell Press is an imprint of Boydell & Brewer Ltd PO Box 9, Woodbridge, Suffolk IP12 3DF, UK and of Boydell & Brewer Inc. -

1962 the Witness, Vol. 47, No. 32

Tte WITN OCTOBER 4, 1962 publication. and reuse for required Permission DFMS. / Church Episcopal the of Archives 2020. Copyright CHURCH OF THE EPIPHANY, NEW YORK RECTOR HUGH McCANDLESS begins in this issue a series of three articles on a method of evangelization used in this parish. The drawing is by a parishioner, Richard Stark, M.D. SOME TEMPTATIONS OF THE CAMPUS SERVICES The Witness SERVICES In Leading Churches For Christ and His Church In Leading Churches THE CATHEDRAL CHURCH CHRIST CHURCH OF ST. JOHN THE DIVINE EDITORIAL BOARD Sunday: Holy Communion 7, 8, 9, 10; CAMBRIDGE, MASS. Morn ing Prayer, Holv Communion W. NORMAN PITTENGER, Chairman and Sermon, 11; Evensong and W. B. SPOFFORD SR., Managing Editor The Rev. Gardiner M. Day, Rector sermon, 4. CHARLES J. ADAMEK; O. SYDNEY BARR; LEE Sunday Services: 8:00, 9:30 and Morning Prayer and Holy Communion BELFORD; KENNETH R. FORBES; ROSCOE T. 11:15 a.m. Wed. and Holy Days: 7:15 (and 10 Wed.); Evensong, 5. FOUST; GORDON C. GRAHAM; ROBERT HAMP- 8:00 and 12:10 p.m. SHIRE; DAVID JOHNSON; CHARLES D. KEAN; THE HEAVENLY REST, NEW YORK GF-ORGE MACMURRAY; CHARLES MARTIN; CHRIST CHURCH, DETROIT 5th Avenue at 90th Street ROBERT F. MCGREGOR; BENJAMIN MINIFLE; SUNDAYS: Family Eucharist 9:00 a.m. J. EDWARD MOHR; CHARLES F. PENNIMAN; 976 East Jefferson Avenue Morning Praver and Sermon 11:00 •i m. (Choral Eucharist, first Sun- WILLIAM STRINGFELLOW; JOSEPH F. TITUS- The Rev. William B. Sperry, Rector 8 and 9 a.m. Holy Communion WEEKDAYS: Wednesdays: Holv Com- munion 7:30 a.m.; Thursdavs, Holy (breakfast served following 9 a.m. -

Edited by Marcus K. Harmes, Lindsay Henderson, BARBARA HARMES and Amy Antonio

i The British World: Religion, Memory, Society, Culture Refereed Proceedings of the conference Hosted by the University of Southern Queensland, Toowoomba, July 2nd -5th, 2012 Edited by Marcus K. Harmes, Lindsay Henderson, BARBARA HARMES and amy antonio ii © The Contributors and Editors All rights reserved. Except as permitted under current legislation no part of this work may be photocopied, stored in a retrieval system, published, performed in public, adapted, broadcast, transmitted, recorded or reproduced in any form or by any means, without the prior permission of the copyright owners. First published 2012 British World Conference, University of Southern Queensland, Toowoomba www. usq.edu.au/oac/Research/bwc National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication Data Author: British World Conference (2012 : Toowoomba, Qld.) Title: The British world: religion, memory, society, culture: refereed proceedings of the conference hosted by the University of Southern Queensland, Toowoomba, July 2nd to July 5th, 2012 / Marcus K Harmes editor, author ... [et al]. ISBN: 9780987408204 (hbk.) 9780987408211 (pdf) Subjects: Civilization--English influences--Congresses. Other Authors/Contributors: Harmes, Marcus K. University of Southern Queensland. Faculty of Arts. Dewey Number: 909 Printed in Australia by CS Digital Print iii Contents Introduction vii Esoteric knowledge 1.Burning Prophecies: The Scholastic Tradition of Comet Interpretation as found in the Works of the Venerable Bede Jessica Hudepohl, University of Queensland 1 2.‘Words of Art’: -

October 2019

OCTOBER 2019 Love, marriage and unbelief CHURCH AND HOME LIFE WITH A NON-CHRISTIAN PLUS Do we really want God’s will done? Persecution in 21st-century Sydney PRINT POST APPROVED 100021441 ISSN 2207-0648 ISSN 100021441 APPROVED PRINT POST CONTENTS COVER Do we know how to support and love friends and family when a Christian is married to a non- Christian? “I felt there was a real opportunity... to Sydney News 3 acknowledge God’s Australian News 4 hand in the rescue”. Simon Owen Sydney News World News 5 6 Letters Southern cross OCTOBER 2019 Changes 7 volume 25 number 9 PUBLISHER: Anglican Media Sydney Essay 8 PO Box W185 Parramatta Westfield 2150 PHONE: 02 8860 8860 Archbishop Writes 9 FAX: 02 8860 8899 EMAIL: [email protected] MANAGING EDITOR: Russell Powell Cover Feature 10 EDITOR: Judy Adamson 2019 ART DIRECTOR: Stephen Mason Moore is More 11 ADVERTISING MANAGER: Kylie Schleicher PHONE: 02 8860 8850 OCTOBER EMAIL: [email protected] Opinion 12 Acceptance of advertising does not imply endorsement. Inclusion of advertising material is at the discretion of the publisher. Events 13 cross SUBSCRIPTIONS: Garry Joy PHONE: 02 8860 8861 Culture 14 EMAIL: [email protected] $44.00 per annum (Australia) Southern 2 SYDNEY NEWS Abortion protests have limited success Choose life: participants in the Sydney protest against the abortion Bill before NSW Parliament. TWO MAJOR PROTESTS AND TESTIMONY TO A PARLIAMENTARY INQUIRY BY ARCHBISHOP GLENN Davies and other leaders has failed to stop a Bill that would allow abortion right up until birth. But the interventions and support of Christian MPs resulted in several amendments in the Upper House of State Parliament. -

Collection Name

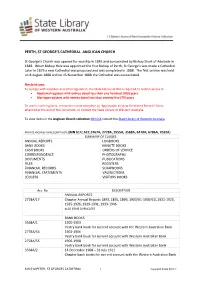

PERTH, ST GEORGE’S CATHEDRAL. ANGLICAN CHURCH St George’s Church was opened for worship in 1845 and consecrated by Bishop Short of Adelaide in 1848. When Bishop Hale was appointed the first Bishop of Perth, St George’s was made a Cathedral. Later in 1879 a new Cathedral was proposed and was completed in 1888. The first service was held on 8 August 1888 and on 15 November 1888 the Cathedral was consecrated. Restrictions To comply with adoption and other legislation, the State Library of WA is required to restrict access to Baptismal registers with entries dated less than one hundred (100) years Marriage registers with entries dated less than seventy five (75) years To access such registers, researchers must complete an 'Application to View Restricted Records' form, attached at the end of this document, or contact the State Library of Western Australia. To view items in the Anglican Church collection MN 614 contact the State Library of Western Australia PRIVATE ARCHIVES MANUSCRIPT NOTE (MN 614; ACC 2467A, 2778A, 3555A, 3568A, 6470A, 6786A, 7032A) SUMMARY OF CLASSES ANNUAL REPORTS LOGBOOKS BANK BOOKS MINUTE BOOKS CASH BOOKS ORDERS OF SERVICE CORRESPONDENCE PHOTOGRAPHS DOCUMENTS PUBLICATIONS FILES REGISTERS FINANCIAL RECORDS SCRAPBOOKS FINANCIAL STATEMENTS VALEDICTIONS LEDGERS VISITORS BOOKS Acc. No. DESCRIPTION ANNUAL REPORTS 2778A/17 Chapter Annual Reports 1893, 1895, 1899, 1900/01-1909/10, 1921-1923, 1925-1926, 1929-1931, 1933-1946. ALSO SOME DUPLICATES BANK BOOKS 3568A/1 1900-1903 Vestry bank book for current account with the Western Australian Bank 2778A/54 1903-1906 Vestry bank book for current account with Western Australian Bank 2778A/55 1906-1908 Vestry bank book for current account with Western Australian bank 3568A/2 14 December 1908 – 31 July 1911 Chapter bank books for current account with the Western Australian Bank MN 614 PERTH, ST GEORGES CATHEDRAL 1 Copyright SLWA ©2012 Acc. -

Frank Patrick Henagan a Life Well Lived

No 81 MarcFebruah 20ry 142014 The Magazine of Trinity College, The University of Melbourne Frank Patrick Henagan A life well lived Celebrating 40 years of co-residency Australia Post Publication Number PP 100004938 CONTENTS Vale Frank 02 Founders and Benefactors 07 Resident Student News 08 Education is the Key 10 Lisa and Anna 12 A Word from our Senior Student 15 The Southern Gateway 16 Oak Program 18 Gourlay Professor 19 New Careers Office 20 2 Theological School News 21 Trinity College Choir 22 Reaching Out to Others 23 In Remembrance of the Wooden Wing 24 Alumni and Friends events 26 Thank You to Our Donors 28 Events Update 30 Alumni News 31 Obituaries 32 8 10 JOIN YOUR NETWORK Did you know Trinity has more than 20,000 alumni in over 50 different countries? All former students automatically become members of The Union of the Fleur-de-Lys, the Trinity College Founded in 1872 as the first college of the University of Alumni Association. This global network puts you in touch with Melbourne, Trinity College is a unique tertiary institution lawyers, doctors, engineers, community workers, musicians and that provides a diverse range of rigorous academic programs many more. You can organise an internship, connect with someone for some 1,500 talented students from across Australia and to act as a mentor, or arrange work experience. Trinity’s LinkedIn around the world. group http://linkd.in/trinityunimelb is your global alumni business Trinity College actively contributes to the life of the wider network. You can also keep in touch via Facebook, Twitter, YouTube University and its main campus is set within the University and Flickr. -

English Duplicates of Lost Virginia Records

T iPlCTP \jrIRG by Lot L I B RAHY OF THL UN IVER.SITY Of ILLINOIS 975.5 D4-5"e ILL. HJST. survey Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2012 with funding from University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign http://archive.org/details/englishduplicateOOdesc English Duplicates of Lost Virginia Records compiled by Louis des Cognets, Jr. © 1958, Louis des Cognets, Jr. P.O. Box 163 Princeton, New Jersey This book is dedicated to my grandmother ANNA RUSSELL des COGNETS in memory of the many years she spent writing two genealogies about her Virginia ancestors \ i FOREWORD This book was compiled from material found in the Public Record Office during the summer of 1957. Original reports sent to the Colonial Office from Virginia were first microfilmed, and then transcribed for publication. Some of the penmanship of the early part of the 18th Century was like copper plate, but some was very hard to decipher, and where the same name was often spelled in two different ways on the same page, the task was all the more difficult. May the various lists of pioneer Virginians contained herein aid both genealogists, students of colonial history, and those who make a study of the evolution of names. In this event a part of my debt to other abstracters and compilers will have been paid. Thanks are due the Staff at the Public Record Office for many heavy volumes carried to my desk, and for friendly assistance. Mrs. William Dabney Duke furnished valuable advice based upon her considerable experience in Virginia research. Mrs .Olive Sheridan being acquainted with old English names was especially suited to the secretarial duties she faithfully performed. -

Anglicans and Abortion: Sydney in the Seventies

COLVILLE: Anglicans and Abortion: Sydney in the Seventies Anglicans and Abortion: Sydney in the Seventies Murray Colville SYNOPSIS This paper considers the public voice of the Anglican Church in Sydney as it discussed and took part in debates concerning the issue of medical abortion during the 1970s. Just prior to this decade, UK law changes and church discussions were bringing this issue on to the table. Contrary to many other voices, the Sydney Anglican position was not supportive of legislative change to make abortion more readily available. Following an initial investigation, the Sydney diocese recommended actions at church, diocesan and State levels calling primarily for better education and support for those considering abortion. While the diocese was not unanimous in its voice on the matter, it found a significant ally in the Roman Catholic Church, with whom it campaigned over the next decade despite a number of other tensions. In 1971, while a court case provided greater security for those seeking abortions, it was still a controversial topic. It surfaced at elections and during significant parliamentary debates as politicians were called on to clarify their personal opinions regarding the matter. The Church aimed to be non-partisan, but spoke independently and with groups such as the Festival of Light, calling for restraint and moral conduct. Archbishop Marcus Loane and Dean of the Cathedral Lance Shilton were prominent Anglican voices throughout this period. While increased support and education were provided over the decade, the results were not always as the Church would have wished. Page | 87 COLVILLE: Anglicans and Abortion: Sydney in the Seventies As the seventies drew to a close, the voice of the Anglican Church is here briefly assessed. -

No. 3 March 2014

No. 3 March 2014 Newsletter of the Religious History Association TheRHA: Newsletter of the Religious History Association March 2014 http:// www.therha.com.au CONTENTS PRESIDENT’S REPORT 1 JOURNAL OF RELIGIOUS HISTORY: EDITORS’ REPORT 3 CORRESPONDENTS’ REPORTS: NEW ZEALAND 5 VICTORIA 6 QUEENSLAND 12 SOUTH AUSTRALIA 12 MACQUARIE 14 TASMANIA 17 UNIVERSITY OF NEW SOUTH WALES 19 UNIVERSITY OF SYDNEY 20 AUSTRALIAN CATHOLIC UNIVERSITY – CENTRE FOR EARLY CHRISTIAN STUDIES 29 AUSTRALIAN CATHOLIC UNIVERSITY – GOLDING CENTRE 31 SYDNEY COLLEGE OF DIVINITY RESEARCH REPORT 33 SUBSCRIPTION AND EDITORIAL ENQUIRIES 36 OFFICE BEARERS 37 Cover photographs: Sent in by Carole M. Cusack: Ancient Pillar, Sanur, Bali (photographed by Don Barrett, April 2013) Astronomical Clock, Prague (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Prague_astronomical_clock) Europe a Prophecy, (frontispiece, also known as The Ancient of Days) printed 1821 by William Blake, The Ancient of Days is the title of a design by William Blake, originally published as the frontispiece to a 1794 work, Europe a Prophecy. (http://www.blakearchive.org/exist/blake/archive/biography.xq?b=biography&targ_div=d1) Madonna Della Strada (Or Lady of the Way) the original – Roma, Chiesa Del SS. Nome Di Gesù All’Argentina The image of The Virgin before whom St Ignatius prayed and entrusted the fledgling Society of Jesus. (http://contemplatioadamorem.blogspot.com.au/2006/12/restored-image-of-madonna-della-strada.html). The Religious History Association exists for the following objects: to promote and advance the study of religious history in Australia to promote the study of all fields of religious history to encourage research in Australian religious history to publish the Journal of Religious History TheRHA: Newsletter of the Religious History Association March 2014 http:// www.therha.com.au Religious History Association - President’s Report for 2013 2103 has seen some changes on the executive as various office-bearers have moved on after a period of considerable service. -

In Good Faith a Historical Study of the Provision of Religious Education for Catholic Children Not in Catholic Schools in New South Wales

In Good Faith A historical study of the provision of religious education for Catholic children not in Catholic Schools in New South Wales: The CCD Movement 1880 - 2000 Submitted by Ann Maree Whenman BA (Hons) DipEd (Macquarie University) Grad Dip RE (ACU) A thesis submitted in total fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Religious Education Faculty of Education Australian Catholic University Research Services Office PO Box 968 North Sydney NSW 2059 Date of Submission: July 2011 Statement of Authorship and Sources This thesis contains no material published elsewhere or extracted in whole or in part from a thesis by which I have qualified for or been awarded another degree or diploma. No parts of this thesis have been submitted towards the award of any other degree or diploma in any other tertiary institution. No other person’s work has been used without due acknowledgment in the main text of the thesis. All research procedures reported in the thesis received the approval of the Human Research Ethics Committee at Australian Catholic University. .................................................................................................. Signature ii Abstract This thesis provides a coherent documented history of the provision of religious education to Catholic children who did not attend Catholic schools in New South Wales from 1880 to 2000. The CCD movement is the title generally assigned to a variety of approaches associated with this activity. The Confraternity of Christian Doctrine (CCD) is an association of clergy and lay faithful, within the Catholic tradition, established in the 16th century, devoted to the work of Catholic religious education. In the 20th century the principal concern of the CCD came to be the religious education of Catholic children who were not in Catholic schools. -

2015 Journal

Journal of the Australian Catholic Historical Society Volume 36 2015 1 Bob Reece, The Invincibles: New Norcia’s aboriginal cricketers 1879-1906, reviewed by Rosa MacGinley, p 287 Odhran O’Brien, Martin Griver Unearthed reviewed by Clement Mulcahy, p 285 Wanda Skowronska, Catholic Converts Roy Williams, Post-God Nation?, from Down Under … And All Over, reviewed by James Franklin, p 308 reviewed by Robert Stove, p 301 2 Journal Editor: James Franklin ISSN: 0084-7259 Contact General Correspondence, including membership applications and renewals, should be addressed to The Secretary ACHS PO Box A621 Sydney South, NSW, 1235 Enquiries may also be directed to: [email protected] Executive members of the Society President: Dr John Carmody Vice Presidents: Prof James Franklin Mr Geoffrey Hogan Secretary: Dr Lesley Hughes Treasurer: Ms Helen Scanlon ACHS Chaplain: Fr George Connolly Cover image: Archbishop Mannix makes a regular visit to the Little Sisters of the Poor hostel for the aged, 1940s. Original image supplied by Michael Gilchrist. See book reviews, p 289 3 Journal of the Australian Catholic Historical Society Volume 36 2015 Contents Julia Horne, Political machinations and sectarian intrigue in the making of Sydney University. 4 Peter Cunich, The coadjutorship of Roger Bede Vaughan, 1873-77. 16 Cherrie de Leiuen, Remembering the significant: St John’s Kapunda, South Australia .......................................................43 Lesley Hughes, The Sydney ‘House of Mercy’: The Mater Misericordiae Servants’ Home and Training School, -

DALKIN, ROBERT NIXON (BOB) (1914–1991), Air Force Officer

D DALKIN, ROBERT NIXON (BOB) (1960–61), staff officer operations, Home (1914–1991), air force officer and territory Command (1957–59), and officer commanding administrator, was born on 21 February 1914 the RAAF Base, Williamtown, New South at Whitley Bay, Northumberland, England, Wales (1963). He had graduated from the RAF younger son of English-born parents George Staff College (1950) and the Imperial Defence Nixon Dalkin, rent collector, and his wife College (1962). Simultaneously, he maintained Jennie, née Porter. The family migrated operational proficiency, flying Canberra to Australia in 1929. During the 1930s bombers and Sabre fighters. Robert served in the Militia, was briefly At his own request Dalkin retired with a member of the right-wing New Guard, the rank of honorary air commodore from the and became business manager (1936–40) for RAAF on 4 July 1968 to become administrator W. R. Carpenter [q.v.7] & Co. (Aviation), (1968–72) of Norfolk Island. His tenure New Guinea, where he gained a commercial coincided with a number of important issues, pilot’s licence. Described as ‘tall, lean, dark including changes in taxation, the expansion and impressive [with a] well-developed of tourism, and an examination of the special sense of humour, and a natural, easy charm’ position held by islanders. (NAA A12372), Dalkin enlisted in the Royal Dalkin overcame a modest school Australian Air Force (RAAF) on 8 January education to study at The Australian National 1940 and was commissioned on 4 May. After University (BA, 1965; MA, 1978). Following a period instructing he was posted to No. 2 retirement, he wrote Colonial Era Cemetery of Squadron, Laverton, Victoria, where he Norfolk Island (1974) and his (unpublished) captained Lockheed Hudson light bombers on memoirs.