Political Rights and Suffrage in the Hungarian Constitution

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reversing Privatization and Re-Nationalizing Pensions in Hungary

ESS – Extension of Social Security Reversing Privatization and Re-Nationalizing Pensions in Hungary Dorottya Szikra ESS – Working Paper No. 66 Social Protection Department INTERNATIONAL LABOUR OFFICE, GENEVA Copyright © International Labour Organization 2018 Publications of the International Labour Office enjoy copyright under Protocol 2 of the Universal Copyright Convention. Nevertheless, short excerpts from them may be reproduced without authorization, on condition that the source is indicated. For rights of reproduction or translation, application should be made to ILO Publications (Rights and Licensing), International Labour Office, CH-1211 Geneva 22, Switzerland, or by email: [email protected]. The International Labour Office welcomes such applications. Libraries, institutions and other users registered with a reproduction rights organization may make copies in accordance with the licences issued to them for this purpose. Visit www.ifrro.org to find the reproduction rights organization in your country. ISSN 1020-9581; 1020-959X (web pdf) The designations employed in ILO publications, which are in conformity with United Nations practice, and the presentation of material therein do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the International Labour Office concerning the legal status of any country, area or territory or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers. The responsibility for opinions expressed in signed articles, studies and other contributions rests solely with their authors, and publication does not constitute an endorsement by the International Labour Office of the opinions expressed in them. Reference to names of firms and commercial products and processes does not imply their endorsement by the International Labour Office, and any failure to mention a particular firm, commercial product or process is not a sign of disapproval. -

Hungary Must Provide Space for Civil Society

Hungary must provide space for civil society No. 1-2016 Hungarian authorities have orchestrated a crack-down on human rights groups unprecedented since the end of the communist era. Alongside Russia, Uganda, Ecuador and China, Hungary sticks out as the only member country of the European Union which puts undue pressure on human rights groups. Hungary’s Prime Minister Viktor Orbán has repeated a Putin-inspired idea of monitoring foreign-funded civil society organizations, described by state authorities as “agents of foreign powers”. This Policy Paper argues that Hungary should reconsider its policies, which are hurting not only the country’s international image, but also have negative consequences at home. Worldwide, the trend is well-known: A large number of countries pass restrictive laws and make the operations of civil society organisations difficult. Over the past three years, more than 60 countries have introduced legislation that place restrictions on non-governmental and civil society organisations. 1 More surprising is that a member state of the EU is entering the club of states that restrict the space of civil society. In the same speech in which Prime Minister Orbán described foreign-funded organizations as foreign agents, he made it clear that the government is now openly embracing the characteristics of an illiberal state. 2 A democratic state does not necessarily have to be liberal, according to the Prime Minister. Liberal values, in particular a concept of freedom which implies that the individual can do whatever s-/he wants, as long as s-/he does not infringe on the freedom of others, “today incorporate corruption, sex and violence”. -

Codebook CPDS I 1960-2013

1 Codebook: Comparative Political Data Set, 1960-2013 Codebook: COMPARATIVE POLITICAL DATA SET 1960-2013 Klaus Armingeon, Christian Isler, Laura Knöpfel, David Weisstanner and Sarah Engler The Comparative Political Data Set 1960-2013 (CPDS) is a collection of political and institu- tional data which have been assembled in the context of the research projects “Die Hand- lungsspielräume des Nationalstaates” and “Critical junctures. An international comparison” directed by Klaus Armingeon and funded by the Swiss National Science Foundation. This data set consists of (mostly) annual data for 36 democratic OECD and/or EU-member coun- tries for the period of 1960 to 2013. In all countries, political data were collected only for the democratic periods.1 The data set is suited for cross-national, longitudinal and pooled time- series analyses. The present data set combines and replaces the earlier versions “Comparative Political Data Set I” (data for 23 OECD countries from 1960 onwards) and the “Comparative Political Data Set III” (data for 36 OECD and/or EU member states from 1990 onwards). A variable has been added to identify former CPDS I countries. For additional detailed information on the composition of government in the 36 countries, please consult the “Supplement to the Comparative Political Data Set – Government Com- position 1960-2013”, available on the CPDS website. The Comparative Political Data Set contains some additional demographic, socio- and eco- nomic variables. However, these variables are not the major concern of the project and are thus limited in scope. For more in-depth sources of these data, see the online databases of the OECD, Eurostat or AMECO. -

Codebook CPDS III 1990-2012

Codebook: COMPARATIVE POLITICAL DATA SET III 1990-2012 Klaus Armingeon, Laura Knöpfel, David Weisstanner and Sarah Engler The Comparative Political Data Set III 1990-2012 is a collection of political and institutional data. This data set consists of (mostly) annual data for a group of 36 OECD and/or EU- member countries for the period 1990-20121. The data are primarily from the data set created at the University of Berne, Institute of Political Science and funded by the Swiss National Science Foundation: The Comparative Political Data Set I (CPDS I). However, the present data set differs in several aspects from the CPDS I dataset. Compared to CPDS I Bulgaria, Croatia, Cyprus (Greek part), Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Malta, Poland, Romania, Slovakia and Slovenia have been added. The present data set is suited for cross-national, longitudinal and pooled time series analyses. The data set contains some additional demographic, socio- and economic variables. However, these variables are not the major concern of the project and are thus limited in scope. For more in-depth sources of these data, see the online databases of the OECD. For trade union membership, excellent data for European trade unions is provided by Jelle Visser (2013). When using the data from this data set, please quote both the data set and, where appropriate, the original source. This data set is to be cited as: Klaus Armingeon, Laura Knöpfel, David Weisstanner and Sarah Engler. 2014. Comparative Political Data Set III 1990-2012. Bern: Institute of Political Science, University of Berne. Last updated: 2014-09-30 1 Data for former communist countries begin in 1990 for Bulgaria, Cyprus, Czech Republic, Hungary, Malta, Romania and Slovakia, in 1991 for Poland, in 1992 for Estonia and Lithuania, in 1993 for Lativa and Slovenia and in 2000 for Croatia. -

Republic of Hungary

Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights REPUBLIC OF HUNGARY PARLIAMENTARY ELECTIONS 11 April 2010 OSCE/ODIHR Election Assessment Mission Report Warsaw 9 August 2010 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ......................................................................................................................... 1 II. INTRODUCTION AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS.............................................................................. 2 III. BACKGROUND..................................................................................................................................... 3 IV. LEGAL FRAMEWORK........................................................................................................................ 3 A. OVERVIEW ............................................................................................................................................... 3 B. SUFFRAGE ................................................................................................................................................. 4 C. SECRECY OF THE VOTE ........................................................................................................................... 5 V. ELECTORAL SYSTEM............................................................................................................................. 5 A. OVERVIEW ............................................................................................................................................... 5 B. EQUALITY OF THE VOTE ......................................................................................................................... -

Thesis Krisztina Hetyesi

AALBORG UNIVERSITY If you come to Hungary… Hungarian Civil Society Initiatives in the wake of the influx of refugees Krisztina Hetyési Master Thesis, Global Refugee Studies, Department of Political Science, Fall 2016 Supervisor: Michael Alexander Ulfstjerne Abstract In 2015, an unexpected influx of migrants arrived in Hungary which resulted in various measures by the government and the mainly negative discourse on the migrants in the Hungarian media. However, despite the Government’s anti-immigration campaign, a small segment of the Hungarian society understood the need of these people and joined forces to provide aid. Facebook-based volunteer grassroots groups emerged and provided street-based social aid which was – unlike in many other European countries – a fairly new phenomenon in Hungary. This thesis analyses the emergence and nature of these volunteer-based grassroots groups in Hungary, as well as their operation, motivations, and relation to other stakeholders. As a method, this thesis uses case study and document analysis together with several theories. The collected data consists of online sources, such as information collected from web pages and Facebook pages of the grassroots groups and online newspaper articles. The data from documents is organized into major themes, categories, and case examples through content analysis followed by thematic analysis, which implies a careful, more focused re-reading, review, and interpretation of the data. The analysis consists of three parts. The first part examines the organizational structure and positioning of the grassroots groups by applying the New Social Movements (NSMs) approach. The second part investigates the underlying motivational drivers of volunteers to engage in providing street-based assistance to migrants by applying a modified multifactor model, the Volunteer Motivation Inventory (VMI). -

E.Saltman Final Thesis Submission

TURNING RIGHT A Case Study on Contemporary Political Socialization of the Hungarian Youth Erin Marie Saltman School of Slavonic and East European Studies University College London (UCL) Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science 2014 1 I, Erin Marie Saltman, confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. X__________________________________ 2 ABSTRACT Young Central and Eastern Europeans are growing up in newly solidifying democratic political systems with a parent generation raised under an entirely different regime. In order to comprehend future sociopolitical dynamics within these countries it is crucial to question how the youth are developing their political knowledge and how they are engaging in political activism. As such, political socialization theory provides a lens for analyzing what forms youth activism is taking as well as tracking the roots of current political trends. Political socialization, as a theory, is relatively straightforward. Experiences and influences of various agents that affect an individual in their earlier years have a significant impact on political outlooks, activism and values in later years. However, implied within this theory, ‘political socialization’ is also a process and a field of research with a variety of methods and research structures. Through primarily qualitative analysis, the research in this case study investigates the influences behind post-communist political trends among the youth, targeting the primary agents of socialization: the family unit, educational institutions and the media. These agents are analyzed in the context of developing partisanships and activism within political parties and grassroots social movements. -

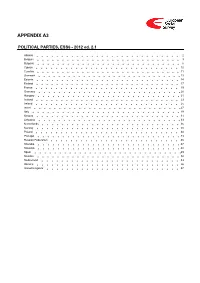

ESS6 Appendix A3 Political Parties Ed

APPENDIX A3 POLITICAL PARTIES, ESS6 - 2012 ed. 2.1 Albania 2 Belgium 3 Bulgaria 6 Cyprus 10 Czechia 11 Denmark 13 Estonia 14 Finland 17 France 19 Germany 20 Hungary 21 Iceland 23 Ireland 25 Israel 27 Italy 29 Kosovo 31 Lithuania 33 Netherlands 36 Norway 38 Poland 40 Portugal 43 Russian Federation 45 Slovakia 47 Slovenia 48 Spain 49 Sweden 52 Switzerland 53 Ukraine 56 United Kingdom 57 Albania 1. Political parties Language used in data file: Albanian Year of last election: 2009 Official party names, English 1. Partia Socialiste e Shqipërisë (PS) - The Socialist Party of Albania - 40,85 % names/translation, and size in last 2. Partia Demokratike e Shqipërisë (PD) - The Democratic Party of Albania - 40,18 % election: 3. Lëvizja Socialiste për Integrim (LSI) - The Socialist Movement for Integration - 4,85 % 4. Partia Republikane e Shqipërisë (PR) - The Republican Party of Albania - 2,11 % 5. Partia Socialdemokrate e Shqipërisë (PSD) - The Social Democratic Party of Albania - 1,76 % 6. Partia Drejtësi, Integrim dhe Unitet (PDIU) - The Party for Justice, Integration and Unity - 0,95 % 7. Partia Bashkimi për të Drejtat e Njeriut (PBDNJ) - The Unity for Human Rights Party - 1,19 % Description of political parties listed 1. The Socialist Party of Albania (Albanian: Partia Socialiste e Shqipërisë), is a social- above democratic political party in Albania; it is the leading opposition party in Albania. It seated 66 MPs in the 2009 Albanian parliament (out of a total of 140). It achieved power in 1997 after a political crisis and governmental realignment. In the 2001 General Election it secured 73 seats in the Parliament, which enabled it to form the Government. -

Center-Right Parties in East Central Europe and Their Return to Power in the 2000S

WHY HAND OW WE WON Center-Right Parties in East Central Europe and Their Return to Power in the 2000s PETER UČEŇ and JAN ERIK SUROTCHAK (editors) WHY AND HOW WE WON Center-Right Parties in East Central Europe and Their Return to Power in the 2000s Editors: Peter Učeň and Jan Erik Surotchak © International Republican Institute, Bratislava 2013. Graphic design: Stano Jendek | Renesans, s. r. o. Printing production: Renesans, s. r. o. Obsah PREFACE .................................................................................................................................... V DiD WE EvER LOSE? THE BulgARIAN CENTER RigHT REBORN ........................ 5 Roumen Iontchev THE CENTER RigHT IN CROATIA – HOW TO WIN, AgAIN? .................................21 Davor Ivo Stier A LONG HARD ROAD OUT OF OppOsitiON: EXplAINING THE SuccESS OF FIDESz–HUNGARIAN Civic UNION ..........................................31 Márk Szabó THE CONSErvATIVE COMEBACK IN LITHUANIA IN 2008: A PYRRHic victORY? .........................................................................................................49 Mantas Adomėnas FOUR VictORIES: THE MACEDONIAN CASE .............................................................71 Jovan Ananiev WHY WE WON – THE POLISH CASE ...............................................................................85 Marek Matraszek THE CENTEr RigHT IN ROMANIA: BEtwEEN COALITION CONFlicts AND REFORM REspONsibilitiES Dragoş Paul Aligică and Vlad Tarko FROM CulturE StrugglE TO DEVELOPMENTAL REFORMS: THE CASE OF SLOVENIA’s CENTEr RigHT -

The Influence of Voting Advice Applications on Preferences, Loyalties and Turnout: an Experimental Study

Article POLITICAL STUDIES: 2015 Political Studies doi: 10.1111/1467-9248.122132016, Vol. 64(4) 1000–1015 The Influence of Voting Advice © The Author(s) 2015 Reprints and permissions: ApplicationsThe Influence on ofPreferences, Voting Advice Loyalties Applications sagepub.co.uk/journalsPermissions.nav on DOI: 10.1111/1467-9248.12213 andPreferences, Turnout: An Loyalties Experimental and Turnout: Study An psx.sagepub.com Experimental Study Zsolt Enyedi Central European University Voting Advice Applications (VAAs) are increasingly popular, yet little is known about their impact. This article investigates their influence on party choice, party loyalty and electoral participation, relying on a complex experiment conducted before and after the 2010 Hungarian election. Participants were directed to two VAAs, some received advice from one and some from both, while the control group visited none. According to subjective recollections, 7 per cent changed their vote intentions, but according to the panel study the VAAs were unable to direct users to specific parties. Sheer exposure to the advice did not have mobilising or demobilising effects either, but preference- confirming outputs increased party loyalty while preference-disconfirming recommendations decreased it, and double exposure amplified further the impact of the VAAs. Converging advice from two different sources increased the rate of electoral participation, but more by provoking, rather than by persuading, the users. Keywords: voting advice applications; party choice; electoral participation; experiment; political parties Voting Advice Applications (VAAs) – that is, websites that identify the user’s proximity to candidates and parties based on a set of political questions – are becoming increasingly popular across Europe and have also reached North America, the Arab World and Latin America (Mendez, 2012; Wall et al., 2012). -

2017 Civil Society Organization Sustainability Index

STRENGTHENING STRENGTHENING CIVIL SOCIETY CIVIL SOCIETY GLOBALLY GLOBALLY 2017 CIVIL SOCIETY ORGANIZATION SUSTAINABILITY INDEX FOR CENTRAL AND EASTERN EUROPE AND EURASIA 21st EDITION - SEPTEMBER 2018 2017 CIVIL SOCIETY ORGANIZATION SUSTAINABILITY INDEX FOR CENTRAL AND EASTERN EUROPE AND EURASIA 21st EDITION - SEPTEMBER 2018 Developed by: United States Agency for International Development Bureau for Democracy, Conflict and Humanitarian Assistance Center of Excellence on Democracy, Human Rights and Governance In Partnership With: FHI 360 International Center for Not-for-Profit Law (ICNL) Acknowledgment: This publication was made possible through support provided by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) under Cooperative Agreement No. AID-OAA-LA-17-00003. Disclaimer: The opinions expressed herein are those of the panelists and other project researchers and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or FHI 360. Cover Photo: Social Weekend’s Hackathon gathers 300 people to develop public benefit ideas (February 2017). The Hackathon was organized by Social Weekend - the largest contest of projects to attract motivated professionals from different fields to develop ideas useful to society. Photo Credit: USAID/Belarus TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................................................... i ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ....................................................................................................................................... -

Hungarian Party Websites and Parliamentary Elections Norbert Merkovity UNIVERSITY of SZEGED, HUNGARY

Hungarian party websites and parliamentary elections Norbert Merkovity UNIVERSITY OF SZEGED, HUNGARY ABSTRACT: Analysis of party websites was one of the popular research fi elds of political communica- tion in the 1990s. It was an interesting question as to how politics and the Internet are becoming con- nected to one another. However, with the appearance of Web 2.0, these surveys have become pointless, since the emphasis has moved to websites supporting the emergence of online communities. Research of Hungarian party websites has not yet been completed. Adapting to this new trend, researchers have begun to turn their attention to a completely new fi eld of investigation. Th is study makes an attempt to analyse the changes in the informative and interactive functions of Hungarian party websites on the basis of three diff erent eras (the 1990s, the mid-2000s and the present). Finally, with an international comparison, it evaluates the situation of websites in 2010. KEYWORDS: political communication, party websites, new ICTs, elections, communication interac- tivity INTRODUCTION: PARTIES IN THE NEW MEDIA SPACE Fift een years ago, nobody would have insisted on parties and politicians having a party website as a channel of communication. Even before that time, politicians did not deny the importance of new media, but they found that world rather strange. Th e American ex-vice president, Al Gore, argued that from Information and Com- munication Technologies (ICTs) “we will derive robust and sustainable economic progress, strong democracies, better solutions to global and local environmental challenges, improved health care, and — ultimately — a greater sense of shared stewardship of our small planet” (1995, p.