Chaos, Accomplishment, and Work, Or, What I Learned on Paternity Leave

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Paternity Trials Are Usually Required to Be Held While the Child Is Quite Young Because of the Operation of the Statute of Limitations

Marquette Law Review Volume 50 Article 2 Issue 3 April 1967 The rT ial of a Paternity Case Judge Marvin C. Holz Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.marquette.edu/mulr Part of the Law Commons Repository Citation Judge Marvin C. Holz, The Trial of a Paternity Case, 50 Marq. L. Rev. 450 (1967). Available at: http://scholarship.law.marquette.edu/mulr/vol50/iss3/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Marquette Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Marquette Law Review by an authorized administrator of Marquette Law Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE TRIAL OE A PATERNITY CASE Judge Marvin C. Holz* CONTENTS PRELIMINARY CONSIDERATION ................................. 453 FORM OF TRIAL, ISSUES, BURDEN OF PROOF .................... 453 PRESUMPTIONS ............................................ 456 THE COMPLAINANT'S CASE ................................... 460 PROOF OF A PRIMA FACIE CASE ........................... 460 CORROBORATING CIRCUMSTANTIAL EVIDENCE .............. 460 INTIMACY AND OPPORTUNITY ............................. 460 ACTS OUTSIDE CONCEPTIVE PERIOD ........................ 462 DEFENDANT'S ADMISSIONS AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ...... 464 DECLARATION OF THE COMPLAINANT ...................... 467 BIRTH CERTIFICATE .................................... 468 THE DEFENDANT'S CASE ................................... 470 IMPOTENCY AND STERILITY ............................... 471 USE OF BLOOD TESTS .................................... -

Blood Tests in Paternity Litigation Assembly Committee on Judiciary

Golden Gate University School of Law GGU Law Digital Commons California Assembly California Documents 9-22-1980 Blood Tests in Paternity Litigation Assembly Committee on Judiciary Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.law.ggu.edu/caldocs_assembly Part of the Family Law Commons, and the Legislation Commons Recommended Citation Assembly Committee on Judiciary, "Blood Tests in Paternity Litigation" (1980). California Assembly. Paper 220. http://digitalcommons.law.ggu.edu/caldocs_assembly/220 This Hearing is brought to you for free and open access by the California Documents at GGU Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in California Assembly by an authorized administrator of GGU Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TABLE OF CONTENTS Testimony taken on Monday, September 22, 1980 WITNESSES PAGE NO. ASSEMBLYMAN DAVE STIRLING l Author of AB 1981 ROBERT W. PETERSON, J. D. 2 Professor of Law, University of Santa Clara JEFFREY w. MORRIS, Ph.D. I M.D. 14 Director, Paternity Testing Laboratory, l'~emorial Hospital Medical Center of Long Beach BRIAN \A7RAXALL 28 Executive Director, Serological Research Institute BYRON HYHRE, M.D. , Ph.D. 33 Professor of Pathology, School of Medicine, University of California at Los Angeles DOMENICO BERNOCO, D.V.M. 37 Associate Professor of Immunogenetics, University of California at Davis, Associate Research Immu nologist, University of California at Los Angeles cTUDY BOND 43 Supervisor of Paternity Evaluation, Tissue Typing Laboratory, Department of Surgerv, University of California at Los Angeles MAX RAY MICKEY, Ph.D. 45 Biostatistician, School of Medicine, University of California at Los Angeles MICHAEL E. -

2021-2022 House Staff Manual Revised March 25, 2021

2021-2022 HOUSE STAFF MANUAL REVISED MARCH 25, 2021 WELCOME TO UNIVERSITY HEALTH We are so happy to have you as part of our team! University Health is a nationally recognized teaching hospital and network of outpatient healthcare centers, serving the people of Bexar County and beyond with the highest level of care and customer service. We are South Texas’ first Magnet healthcare organization having earned this prestigious accreditation since 2010. Our goal is to be the hospital of choice in our community and throughout South Texas. Our expectation is that you will bring the best of yourself to our hospital and all clinical locations every day, and understand that you are leaving a lasting impression—either good or bad—on every patient and visitor you encounter. We have locations across the community to provide the right level of care in facilities that are warm, welcoming and convenient for our patients. These include: University Hospital (Level I trauma center) More than 25 outpatient care centers Four school-based health centers Three dialysis centers Two ExpressMed urgent care centers Two ambulatory surgery centers Two healthyUexpress mobile units The new Women’s and Children’s Hospital is currently under construction and expected to open in 2023. Please visit UniversityHealthSystem.com to learn more about our services and locations. As a member of our House Staff, you will be practicing at some of these facilities and playing a vital role in the mission of our Health System. You will find additional information about these facilities in the section titled University Health Facilities and Services. -

HOUSE ...No. 3328

HOUSE DOCKET, NO. 3685 FILED ON: 1/18/2019 HOUSE . No. 3328 The Commonwealth of Massachusetts _________________ PRESENTED BY: Stephan Hay _________________ To the Honorable Senate and House of Representatives of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts in General Court assembled: The undersigned legislators and/or citizens respectfully petition for the adoption of the accompanying bill: An Act relative to great-grandparent visitation rights. _______________ PETITION OF: NAME: DISTRICT/ADDRESS: DATE ADDED: Stephan Hay 3rd Worcester 1/16/2019 Steven S. Howitt 4th Bristol 1/24/2019 Dylan A. Fernandes Barnstable, Dukes and Nantucket 1/28/2019 Elizabeth A. Poirier 14th Bristol 1/30/2019 Kay Khan 11th Middlesex 1/30/2019 Jonathan D. Zlotnik 2nd Worcester 1/31/2019 Andres X. Vargas 3rd Essex 1/31/2019 Natalie M. Higgins 4th Worcester 2/1/2019 1 of 1 HOUSE DOCKET, NO. 3685 FILED ON: 1/18/2019 HOUSE . No. 3328 By Mr. Hay of Fitchburg, a petition (accompanied by bill, House, No. 3328) of Stephan Hay and others relative to great-grandparent visitation rights. The Judiciary. The Commonwealth of Massachusetts _______________ In the One Hundred and Ninety-First General Court (2019-2020) _______________ An Act relative to great-grandparent visitation rights. Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives in General Court assembled, and by the authority of the same, as follows: 1 Chapter 119 of the General Laws is hereby amended by striking out section 39D and 2 inserting in place thereof the following section:- 3 Section 39D. If the parents of an -

South Carolina Parenting Opportunity Program Training Manual Revised June 2018

South Carolina Parenting Opportunity Program Making a world of difference for children What a difference a Dad makes! Training Manual SOUTH CAROLINA PARENTING OPPORTUNITY PROGRAM TRAINING MANUAL REVISED JUNE 2018 TABLE OF CONTENTS ABOUT THIS MANUAL .................................................................................................... SECTION 1: BACKGROUND ......................................................................................... 1 THE NEED FOR VOLUNTARY PATERNITY ACKNOWLEDGMENT ..................... WHAT IS PATERNITY ESTABLISHMENT? ............................................................ WHY SHOULD YOU HELP WITH PATERNITY ESTABLISHMENT? ..................... WHAT IS THE PATERNITY ESTABLISHMENT PERCENTAGE? .......................... ARE THERE PENALTIES ASSOCIATED WITH PEP? ........................................... WHAT'S THE CURRENT SOUTH CAROLINA PEP STATUS? ............................... SECTION 2: THE SOUTH CAROLINA PARENTING OPPORTUNITY PROGRAM ...... 4 THE IMPORTANCE OF ESTABLISHING PATERNITY ........................................... GOALS OF THE SOUTH CAROLINA PARENTING OPPORTUNITY PROGRAM THE ROLE OF HOSPITALS IN PATERNITY ACKNOWLEDGMENT ..................... THE ROLE OF LOCAL VITAL RECORDS OFFICES IN PATERNITY ACKNOWLEDGMENT ............................................................................................. THE ROLE OF THE VITAL RECORDS CENTRAL OFFICE IN PATERNITYACKNOWLEDGMENT ......................................................................... THE ROLE OF THE DSS CHILD SUPPORT -

Effective Paternity Establishment Practices

EFFCf PATERN ESTABLISHMNT PRACfICES TECHCAL REPORT RICHAD P. KUSSEROW INSPECfOR GENERA OAI 06-89-00911 JANUARY 1990 For Further Information: A condensed executive version of the report and additional copies of this technical report are available from the Superintendent of Documents, Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C. 20402. EXCU SUMY PUR This report describes effective State and local paternity establishment practices barriers to a succssful paternity establishment program, and perceptions of the program s cost/bnefit. BACKGROUN The Congress, concerned by the increasing costs of the Aid to Familes with Dependent Children (AFC) program, amended the Social Security Act in 1975 1984 and 1988 to create and then to strengthen the Child Support Enforcement (CSE) program. The 1988 amendments required State CSE programs, for the first time, to meet a specific paternity establishment percentage. Two recent evaluations of States' performance in child support enforcement conducted by a U.S. House of Representatives subcommittee and the General Accounting Offce show that many States are not pursuing paternity establishment vigorously and successfully. These findings have serious cost implications for the States because States are subject to fiscal penalties if they cannot meet their paternity establishment percentage goal, and most paternity suits are brought in behalf of single mothers applying for AFC. We intervewed 77 managers, supervsors and legal personnel at 13 effective practice sites about barrers and key improvements to the paternity establishment process. We defined effective practices as procedures which improve the number of paternities established, case decision accuracy and/or case management effciency. EFFCT PRACfCE SUMY States should consider adopting the following seven effective practices to improve paternity establihment in their Child Support Enforcement programs. -

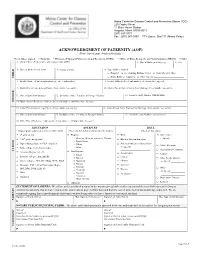

ACKNOWLEDGMENT of PATERNITY (AOP) (Please Type Or Print Clearly in Black Ink.)

Maine Center for Disease Control and Prevention (Maine CDC) 220 Capitol Street 11 State House Station Augusta, Maine 04333-0011 (207) 287-3771 Fax : (207) 287-1093 TTY Users: Dial 711 (Maine Relay) ACKNOWLEDGMENT OF PATERNITY (AOP) (Please type or print clearly in black ink.) Check where signed: □ Hospital □ Division of Support Enforcement and Recovery (DSER) □ Office of Data, Research, and Vital Statistics (DRVS) □ Other 1. Child’s Name (First, middle, other middle, last, suffix) 2. Date of Birth (mm/dd/yyyy) 3. Sex 4. Place of Birth (City or town) 5. County of Birth 6. Type of Place of Birth □ Hospital □ Freestanding Birthing Center □ Clinic/Doctor’s Office CHILD □ Home Birth □ Unknown □ Other (Specify)__________________________ 7. Facility Name (If not an institution, give street and number) 8. Facility Address (Street and number, city/town, state, zip code) 9. Mother/Parent Current Legal Name (First, middle, last, suffix) 10. Mother/Parent Name Prior to First Marriage (First, middle, last, suffix) 11. Date of Birth (mm/dd/yyyy) 12. Birthplace (State, Territory, or Foreign Country) 13. Social Security Number (xxx-xx-xxxx) MOTHER 14. Mother/Parent Residence Address (Street and number, city/town, state, zip code) 15. Father/Parent Current Legal Name (First, middle, last, suffix) 16. Father/Parent Name Prior to First Marriage (First, middle, last, suffix) 17. Date of Birth (mm/dd/yyyy) 18. Birthplace (State, Territory, or Foreign Country) 19. Social Security Number (xxx-xx-xxxx) 20. Father/Parent Residence Address (Street and number, -

Dr House Season 2 Subtitles

Dr house season 2 subtitles House M.D.. Season 8 | Season 7 | Season 6 | Season 5 | Season 4 | Season 3 | Season 2 | Season 1. #, Episode, Amount, Subtitles. 2x24, No Reason, filename: House_M.D. - season subtitles amount: subtitles list: House M.D. - 2x01 - House M.D. - 2x01 - Sort list by date. Subtitles -Arabic · OzOz. Pirate. D. House MD Season 2 Complete BluRay p .ﺗﺠﻤﯿﻊ ﺗﺮﺟﻤﺎت اﻟﻤﻮﺳﻢ اﻟﺜﺎﻧﻲ - ﺷﻜﺮا ﻟﺠﻤﯿﻊ اﻟﻤﺘﺮﺟﻤﯿﻦ rated good; Not rated; Visited . House M.D. - Second Season Imdb. Release info: Anonymous. Subtitles for all 24 episodes. Subtitle details; Preview. Subtitles rated good; Not rated; Visited Spell Check, perfect sync on this release: Arabic subtitle for House M.D. - Second Season. House M.D. - Second Season Imdb. Release info: House MD Season 2. A commentary by. House M.D. Season 2 HDTV by Lupin [1 - 12] Arabic subtitles · House.S02 Another Timing Arabic subtitles · House M.D. Season 08 COMPLETE p BluRay x MB Pahe .. M.D. The Complete Season 7, 2 years ago, 23, KB, I Only Collect The Subs. Watch Online House M.D. Season 2 HD with Subtitles House M.D. Online Streaming with english subtitles All Episodes HD Streaming eng sub Online HD. Download the popular multi language subtitles for House M D S2e22 Subtitles Forever Season 2 Episode 22 English Subtitles. Best Subsmax subtitles daily. house md season 6 english subtitles download Download Link . House M. D. (season 1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8) download full episodes. House subtitles Episode list and. There are so many out there online. But, Netflix has all the seasons there, so I suggest go there first. -

Instructions for Completing the Oregon Report of Live Birth on Paper

Center for Health Statistics Center for Public Health Practice Public Health Division Oregon Health Authority Instructions for completing the Oregon Report of Live Birth on paper These instructions are intended for births occurring outside of a licensed facility reported on paper reports of live birth (Certificate of Live Birth Form 45-1). Mailing Address Oregon Vital Records P.O. Box 14050 Portland, OR 97293-0050 Registration Manager: Marsha Trump 971-673-1191 [email protected] Document Change Activity The following is a record of the changes that have occurred on this document from the time of its original approval Rev. date Change Description Author Date May 13, 2011 Revised instructions regarding attendant certifier for Hampton 8/3/11 out of facility birth to comply with ORS 432.206(3) October 1, Removed items as reportable to match national Hampton 8/15/14 2014 standards; recognition of marriage between persons of same sex November 24, Revised instructions to match most recent Certificate Jackson 11/30/15 2015 of Live Birth Form 45-1. March 3, 2018 Revised instructions on new sex designation Zapata 03/03/18 May 11, 2020 Revised contact information Ruden 5/11/20 GENERAL INFORMATION – OREGON REPORTS OF LIVE BIRTH Births that occur outside a licensed facility create specific legal obligations and practical limitations. The attending physician, midwife, or other person as identified by statute (below) also referred to as the certifier of the birth, is required to report births that occur outside of a facility to the Center for Health Statistics within five days. This is different from births occurring in a licensed facility where the facility has the legal obligation to report the birth. -

VPEP Training Manual.Pdf

Virginia Paternity Establishment Program Training Manual Virginia Paternity Establishment Program Training Manual TABLE OF CONTENTS Page # ABOUT THIS MANUAL .......................................................................................................................................... 6 SECTION 1: BACKGROUND .................................................................................................................................. 7 The Need for Voluntary Paternity Acknowledgment ........................................................................................ 7 What is Paternity Establishment? .............................................................................................................................. 8 What is the Legal Basis for the Virginia Paternity Establishment Program (VPEP)? ........................... 9 Federal Legislation ................................................................................................................................................... 9 State Legislation ..................................................................................................................................................... 10 What Is the Paternity Establishment Percentage (PEP)? .............................................................................. 10 Are There Penalties Associated with PEP? ......................................................................................................... 12 SECTION 2: THE VIRGINIA PATERNITY ESTABLISHMENT PROGRAM ............................................. -

The Paternity Test and the Cultural Logic of Paternity

WHO'S YOUR DADDY? THE PATERNITY TEST AND THE CULTURAL LOGIC OF PATERNITY by Kathalene A. Razzano A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of George Mason University in Partial Fulfillment of The Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Cultural Studies Director Program Director Dean, College of Humanities and Social Sciences Date: );! Spring Semester 2012 George Mason University Fairfax, VA Who’s Your Daddy?: The Paternity Test and the Cultural Logic of Paternity A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at George Mason University by Kathalene A. Razzano Master of Arts The Pennsylvania State University, 1997 Bachelor of Arts University of Maryland, College Park, 1995 Director: Timothy Gibson, Professor Department of Communication Spring Semester 2012 George Mason University Fairfax, VA This work is licensed under a creative commons attribution-noderivs 3.0 unported license. ii DEDICATION This is dedicated to those I’ve lost along the way; my teachers, mentors and friends Joe L. Kincheloe, Peter Brunette, and Jeanne Hall; my step-mother Linda Razzano; and my Pop, Gabriel Razzano. I miss each of you but carry you on with me. I also dedicate this dissertation to my Grammies, Audrey Razzano. She’s been waiting for me to (finally) finish so that she can call me “Doctor.” iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank the many friends, relatives, and supporters who have made this happen. Since I’ve been doing this a while, I have a number of people to thank. First, I must thank my dissertation chair Tim Gibson who has been unbelievably supportive, helpful and productively critical. -

Download House Md Season 3 Episode 5

Download house md season 3 episode 5 House M.D. - Season 3: In this provocative and compelling season, House's unpredictable Scroll down. TV Series House M.D. season 5 Download at High Speed! Full Show Where to download House M.D. season 5 episodes? Episode 3. Watch House M.D. Season 3 Episode 5 Download in HD cause Foreman to ponder the strength of true love, and House abuses one too many patients with. and his team. House M.D. (season 1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8) download full episodes. Season 6 episode 22 is missing can this be uploaded please. House M.D. Season 3 Episode 4 Download S03E04 p, M. House M.D. Season 3 Episode 5 Download S03E05 p, M. House MD. Season 3 Episode 4 Lines in the Sand House MD. Season 3 Episode 5 Fools for Love House MD. Season 3 Episode 6 Que Será. The first episode of the Drama, Comedy, Mystery series House M.D. (season 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8) was released in by Fox. Watch House M.D. - Season 3 On Seriesonline, In this provocative and compelling season, Favorite Comment Report Download subtitle 10 Episode 9 Episode 8 Episode 7 Episode 6 Episode 5 Episode 4 Episode 3 Episode 2 Episode 1. Watch House M.D. - Season 3 Full Movie Online Free | Series9 | Gostream | Fmovies Favorite Comment Report Download subtitle 10 Episode 9 Episode 8 Episode 7 Episode 6 Episode 5 Episode 4 Episode 3 Episode 2 Episode 1. House M.d. Season 3 Episode 5 (s03e05) You can also download House M.d.