15 Armani/Architecture the Timelessness and Textures of Space John Potvin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Beauty Power

BEAUTY Contacts: Thea M. Page, 626-405-2260, [email protected] Lisa Blackburn, 626-405-2140, [email protected] POWER Renaissance and Baroque Bronzes & from the Peter Marino Collection PETER MARINO Peter Marino, FAIA, is the principal of Peter Marino Archi - tect PLLC, an internationally acclaimed architecture, plan - ning, and design firm founded in 1978 and based in New York City. Marino’s design contributions in the areas of commercial, cultural, residential, and retail architecture have helped redefine modern luxury, emphasizing materiality, tex - ture, scale, light, and the dialogue between interior and exte - rior. His recent architectural projects include Chanel boutiques in Los Angeles (one on Robertson Boulevard and the other on Rodeo Drive in Beverly Hills) and the Chanel Tower in Ginza, Tokyo; Louis Vuitton boutiques in Shang - hai and Singapore, and the recently opened Louis Vuitton Maison on London’s New Bond Street; a Dior boutique in Shanghai; a fine jewelry boutique in Geneva; Ermenegildo Zegna global flagship stores in Tokyo and Hong Kong; and 170 East End Avenue, a luxury, high-rise condominium on New York’s Upper East Side. Marino was born in New York City. He received an architecture degree from Cornell Univer - sity and began his career with the architecture firms Skidmore Owings & Merrill and I. M. Pei/Cossutta & Ponte. Andy Warhol and Yves Saint Laurent were among Marino’s first clients, with initial commis - sions including the design of Warhol’s seminal Factory space and renovation of his New York townhouse. Friendship with Warhol furthered Marino’s interest in art collecting, a passion he has been able to develop while sourcing artworks for clients and through his work for international museums. -

University of Huddersfield Repository

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Huddersfield Repository University of Huddersfield Repository Anderson, Stacy, Nobbs, Karinna, Wigley, Stephen M. and Larsen, Ewa Collaborative Space: An Exploration of the Form and Function of Fashion Designer and Architect Partnerships Original Citation Anderson, Stacy, Nobbs, Karinna, Wigley, Stephen M. and Larsen, Ewa (2010) Collaborative Space: An Exploration of the Form and Function of Fashion Designer and Architect Partnerships. SCAN Journal of Media Arts Culture, 7 (2). ISSN 1449-1818 This version is available at http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/11458/ The University Repository is a digital collection of the research output of the University, available on Open Access. Copyright and Moral Rights for the items on this site are retained by the individual author and/or other copyright owners. Users may access full items free of charge; copies of full text items generally can be reproduced, displayed or performed and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided: • The authors, title and full bibliographic details is credited in any copy; • A hyperlink and/or URL is included for the original metadata page; and • The content is not changed in any way. For more information, including our policy and submission procedure, please contact the Repository Team at: [email protected]. http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/ :: SCAN | journal of media arts culture :: Page 1 of 8 Home News & Events Journal Magazine Gallery About Search >> Go Collaborative Space: An Exploration of the Form and Function of Fashion Designer and Synopsis Architect Partnerships Refereed articles Stacy Anderson, Karinna Nobbs, Stephen M. -

Über-Wealthy Flock to Soon-To-Open East End Avenue Tower

Über-Wealthy Flock to Soon-To-Open East End Avenue Tower By JILL GARDINER, Staff Reporter of the Sun | August 9, 2007 The neurologists, orthopedic surgeons, and nurses who once milled around this quiet stretch of the Upper East Side, enjoying breathtaking river views from their medical examining rooms, are long gone. And a who's who of real estate, art, fashion, and business will replace them. Nearly three years after Beth Israel Medical Center shuttered its satellite hospital across the street from Gracie Mansion, a far more lavish building is preparing to open. The luxury condominium at 170 East End Ave., between 87th and 88th streets could open as soon as October. Its residents will include the president of Vornado Realty Trust, Michael Fascitelli; an heir to the Bronfman family fortune, Adam Bronfman; a prominent Manhattan art dealer, Dominique Levy; the founder of the clothing chain Club Monaco, Joseph Mimram, and a number of other boldfaced names. Designed by the architect Peter Marino, who created the flagship Giorgio Armani store on Madison Avenue and the Louis Vuitton store on Fifth Avenue, 170 East End Ave. has units priced up to $16 million. The building is more than 90% sold, and includes amenities such as a squash court, golf simulator, a library, and a children's game room that is shown with pinball machines and a foosball table in renderings. "We sold to a very large amount of prominent real estate people," the building's developer and president of Skyline Developers, Orin Wilf, said. "We probably sold 12 or 14 apartments to some of the biggest real estate people in New York." Real estate experts say the opening of the 90-unit building could be the beginning of a transformation of the upscale but sleepy East End Avenue into a new, edgier destination neighborhood for the über-wealthy. -

Designers of New York 2 3 the Best 25 Interior Designers of New York

THE BEST 25 INTERIOR DESIGNERS OF NEW YORK 2 3 THE BEST 25 INTERIOR DESIGNERS OF NEW YORK POWERED by 4 TABLE OF CONTENTS 01AMY LAU 02CENK FIKRI 03CLODAGH 04DRAKE/ 05DUTCH EAST 16PETER 17PETI LAU 18ROBERTO 19RICHARD 20ROCKWELL PAG.10 PAG.12 PAG.14 ANDERSON DESIGN MARINO PAG.56 RINCON MISHAAN GROUP PAG.18 PAG.20 PAG.54 PAG.58 PAG.62 PAG.66 06FOX NAHEM 07HALPERN 08JESSICA 09JOE GINSBERG10MARMOL 21ROTTET 22SASHA BIKOFF 23SARA STORY 25YABU 24VIDESIGNS ASSOCIATES DESIGN GERSTEN PAG.32 RADZINER STUDIO PAG.70 PAG.72 PUSHELBERG PAG.76 PAG.24 PAG.26 INTERIORS PAG.34 PAG.68 PAG.74 PAG.30 11MERVE 12MESHBERG 13NICOLE FULLER 14OVADIA 15PEPE CALDERIN KAHRAMAN GROUP PAG.48 DESIGN GROUP DESIGN PAG.38 PAG.44 PAG.50 PAG.52 NEW YORK Home to some of the biggest companies and design studios in the world, New York City is a “design meca” that’s been growing in creativity, size, and popularity since it’s foundation! It’s a known fact that designers continue to flock to The Big Apple chasing big dreams, despite the impossible odds facing them or the challenges that dog their every step. And why do they continue to do that? Because New York is the City of Dreams and one of the only cities in the world where everything is possible! Every year, iconic works from iconic companies, publications and institutions are released to the world and help influence every single international design movement and design trend on the planet. You can’t be at the top of the design industry if you don’t know what’s happening in New York, and that’s why this major city is one of the biggest design capitals of the world. -

Call Him Monsieur Dior for Proof That Peter Marino Truly Lives and Breathes the Brand, Just Visit the Boutique in Seoul, South Korea Text: Edie Cohen

Call Him Monsieur Dior For proof that Peter Marino truly lives and breathes the brand, just visit the boutique in Seoul, South Korea text: edie cohen 228 INTERIOR DESIGN APRIL.17 APRIL.17 INTERIOR DESIGN 229 Previous spread, left: At the Christian Dior boutique that Peter Marino Architect de signed for Seoul, South Korea, monitors looping video art by Yorame Mevorach Oyoram line the stairwell. Photog raphy: Kristen Pelou/ Christian Dior. Previous spread, right: Powdercoated aluminum paillettes drape a corner of the handbag salon. Pho tography: Luc Castel. Top: Lee Bul’s sculpture, a composition in aluminum chains, acrylic beads, and crystals, hangs above the handbag salon. Photography: Kyungsub Shin/Christian Dior. Bottom: The perfumery’s console has a base in verre églomisé. Photography: Kristen Pelou/Christian Dior. Opposite: The staircase, with Pick a luxury brand. Bulgari, Chanel, Christian Dior, Fendi, Hublot, Louis Vuitton, or Ermenegildo Zegna. Interior Design Hall of Fame its balustrades of mirror member Peter Marino has created exceptional showplaces for them all, from New York and Los Angeles to London, Paris, Rome, Singa- polished stainless steel and pore, Hong Kong, and Tokyo. With the august Dior brand, celebrating its 70th anniversary, Marino can boast of a relationship that was glass, connects five of the established more than 20 years ago, with the redesign of the flagship maison in Paris, and has taken an Asian direction over the past six levels. Photography: Luc Castel. couple of years, with boutiques in Seoul, South Korea, followed by Beijing. Of the two newcomers, Seoul is the mega-store, housed in a ground-up building by Atelier Christian de Portzamparc. -

Les Lalanne at the Raleigh Gardens

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE GORILLAS, BUNNIES AND SHEEP ARE TAKING OVER THE NEWLY DESIGNED RALEIGH GARDENS, INAUGURATING AN IMMERSIVE SCULPTURE EXHIBIT FEATURING WORKS BY CLAUDE AND FRANÇOIS-XAVIER LALANNE AT MIAMI BEACH’S HISTORIC RALEIGH HOTEL Longtime Lalanne Friend, Developer and Investor Michael Shvo, Marks New Raleigh Hotel Renaissance and Commitment to Miami Beach with a Public Tribute to the Iconic Artists Installation image Les Lalanne at The Raleigh Gardens. Courtesy SHVO. © Douglas Friedman. Miami Beach, FL, November 27,2019 – To inaugurate the opening of the newly-designed Raleigh Gardens, real estate developer and investor Michael Shvo and his partners announced their plans for the largest- ever outdoor public exhibition of the work of the late Claude Lalanne (1924-2019) and François-Xavier Lalanne (1927-2008), the artistic duo known together as Les Lalanne. The exhibition, which has been envisioned and created by Shvo, is on public display in a new, immersive, lush, beach-side tropical garden designed by architect Peter Marino, a longtime SHVO collaborator, and Miami landscape architect Raymond Jungles. The exhibition and new garden are free and open to the public through February 29, 2020, between the hours of 12pm to 8pm. The opening of the Raleigh Gardens marks the latest step in the restoration and renewal of the iconic Raleigh Hotel, along with adjacent properties, The Richmond and South Seas, located on Miami Beach’s famed Collins Avenue, which were purchased by SHVO and partners Bilgili Holdings and Deutsche Finance this past summer. In a nod to the Raleigh Hotel’s epic past as an icon of culture and style, Les Lalanne at The Raleigh Gardens is a monumental public art exhibition which animates the newly designed Raleigh Gardens in tribute to the profound legacy of Les Lalanne. -

FA05 Layout 001-032 V4 Copy.Qxd 7/9/16 4:49 PM Page 2

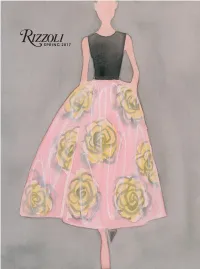

SP17 cover INSIDE LEFT_FULL SIZE V8.qxd:Layout 1 7/9/16 11:24 AM Page 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS RIZZOLI 100 Buildings . .24 Toscanini . .46 The Adirondacks . .44 Watches International XVIII . .102 Adobe Houses . .32 What to Eat for How You Feel: The Appalachian Trail . .44 The New Ayurvedic Kitchen . .11 The Art of Dressing . .39 The Art of Elegance . .13 SKIRA RIZZOLI The Art of Flower Arranging . .28 American Treasures . .51 Ballet for Life . .29 Andrew Wyeth . .50 BEAMS . .36 Carpenters Workshop Gallery . .59 Chocolat . .18 Daniel Lismore . .56 Cinecitta . .46 Enrico Baj . .55 Civil War Battlefields . .21 The Hidden Art . .54 Creating Home . .6 House Style . .48 The Decorated Home . .5 Jim Lambie . .58 Digit@l Girls . .27 Manolo Blahnik: The Art of Shoes . .49 Dior by Mats Gustafson . .47 Mark Tobey . .57 Dora Maar . .14 Painting a Nation . .56 Elizabeth Peyton . .15 Ryan McGinley . .52 Entertaining in the Country . .30 Takashi Murakami . .53 Fashion Forward: 300 Years of Fashion . .3 FuturPiaggio . .42 RIZZOLI/ GAGOSIAN GALLERY The Garden of Peter Marino . .34 Alberto Giacometti, Yves Klein . .81 Gâteaux . .7 Line into Color, Color into Line: Helen Frankenthaler . .80 Giorgio Armani . .76 Painting Paintings (David Reed) 1975 . .80 Grand Complications . .102 Sterling Ruby . .79 Harry Winston . .78 Highland Retreats . .40 UNIVERSE How They Decorated . .38 1000 T-Shirts . .65 I Actually Wore This . .26 Big Shots . .62 In Full Flower . .9 The Bucket List . .60 Jean Dubuffet: Anticultural Positions . .74 Color Your Own Masterpiece . .75 La Colle Noire . .78 Complete Guide to Boating and Seamanship . .71 Les Francaises . -

TOKYO City Walking

ITS Co.,Ltd. / i Travel Square TEL:03-6706-4700 FAX:03-3779-3800 EMAIL: [email protected] WEB: http://i-travel-square.tokyo Day trip : TOKYO City Walking Tokyo is one of the most exciting city in the world. Culture, art, entertainment, fashion, gourmet, sports, we have everything, and you can do everything! In this time, we will introduce you Architecture in Tokyo. Especially we focus to "modernism architecture" which had built after Samurai period ended, when our culture changed rapidly, and "post modern" buildings are also including, each of them has designed by internationally famous architects. Our English speaking guides, who had been trained by real architect, show you with explanation about these buildings, e.g. theme, characteristics, originality, ingenious points, historical and cultural background, secret story. Let's visit these beautiful buildings, with the other view spots, by all means!! Course 1: Omotesando (表参道) ◎ Schedule (4 hours/Walking) 9:00/13:00 Meet at your hotel (※within 23 ward), then move to each town ☆☆ Sample plan ● Nezu Museum(outside)→● Omotesando Hills(enter)→ ● Ota kinen museum(enter)→● Meiji Jingu→● Yoyogi Park while walking to each spots, visit some of buildings and explain the story about them and the town's background ☆☆ Recommended spots in this area ● Meiji Jingu ● Yoyogi Park ● Harajuku ● Aoyama ● Ota kinen museum (Ukiyoe) ☆☆ Buildings designed by well-known architects (only view from outside) ● Nezu Museum/Kengo Kuma ● Tokyu Plaza/Hiroshi Nakamura ● The Jewels of Aoyama/Jun Mitsui ● La Foret Harajuku/Klein Dytham ● La Perla Aoyama/Bruno Moinard ● GYRE/MVRDV ● PRADA/Herzog & de Meuron ● Christian Dior/SANAA ● STELLA McCARTNEY/Takenaka Corp. -

Rodeo Drive - the Podcast Episode Three Launches Today

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Friday, June 26, 2020 Rodeo Drive - The Podcast Episode Three Launches Today Every Detail is The Universe: Michael Chow’s Design for Giorgio Armani LISTEN Beverly Hills, CA– When Giorgio Armani opened his flagship mega boutique on Rodeo Drive in 1988 people were stunned at the 13,000 square feet interior with a sweeping staircase, white gold leaf and glorious light. It was created by Michael Chow, legendary restaurateur and artist. It inspired Armani’s famed uplit runway, became a Hollywood hot spot, and set the trend for retailers to team up with famous architects: think Prada and Rem Koolhaas; Louis Vuitton, Chanel and Peter Marino; Valentino Menswear, Bally and David Chipperfield. Chow’s design for Giorgio Armani Beverly Hills has remained intact. “It’s very simple to be timeless,” says Chow. “You just have to be true to yourself.” But is the age of the vast boutique over? Hear Bronwyn Cosgrave in conversation with Michael Chow, Interior Design magazine editor Edie Cohen and writer and former editor-in-chief of French Vogue Joan Juliet Buck. Michael Chow, photo by Andy Warhol; Rendering of Giorgio Armani’s Rodeo Drive flagship store. Portrait of Edie Cohen; Portrait of Joan Juliet Buck, photo © Les Guzman. Rodeo Drive -The Podcast connects listeners around the world with up to date stories about the past, present and future of the renowned three-block stretch in Beverly Hills, which has now officially reopened post lockdown. Rodeo Drive began as little more than a bridle path. Pioneering designers, hoteliers and entrepreneurs transformed it into a rival to New York’s Fifth Avenue - with sun, palm trees and Hollywood sizzle. -

Walking Tour Map Midtown

www.fmsp.com 22 west 19th street, floor 6 | new york, ny 10011 | +1 212 691 3020 walking tour map [email protected] 80 vine street, suite 202 | seattle, wa 98121 | +1 206 691 0101 midtown nyc 1 American Museum of Natural History 9 Radio City Music Hall 17 Gucci Flagship Store 26 Park Avenue Armory Hall of Planet Earth Building Exterior North American Mammals Dioramas h3 hardy collaboration architecture gucci worldwide store planning Wade Thompson Drill Hall Rose Center for Earth and Space 1260 6th avenue between 50th and 51st streets 725 5th avenue between 56th and 57th streets Company D and E Room Plaza and 77th Street Façade 2000 iald award of merit Board of Officers Room 2000 iesny lumen award of merit Veterans Room ennead architects (formerly polshek partnership) / 2000 new york landmarks conservancy: wiss janney elstner associates lucy g. moses preservation award platt byard dovell white / central park west between 77th and 81st streets herzog & de meuron TKTS Booth The Peninsula Hotel th th 2001 iald award of excellence 10 18 643 park avenue between 66 and 67 streets 2001 iesny lumen citation 2017 iald special citation for inventive perkins eastman / chrofi stonehill & taylor / faithful + gould 2001 iesna edwin guth memorial award of and sensitive reimagining of historic gas duffy square at 47th street and broadway 700 5th avenue between 54th and 55th streets excellence for interior lighting luminaires 2009 iald special citation for remarkable use of light 2017 iesny lumen award of excellence 2010 new york landmarks conservancy: and architecture as an urban intervention lucy g. -

760 Madison Ave New York, Ny March 26, 2019 Cookfox Architects 1 760 Madison 2019

760 MADISON AVE NEW YORK, NY MARCH 26, 2019 COOKFOX ARCHITECTS 1 760 MADISON 2019 E 70TH ST 3RD AVE PARK AVE PARK FIFTH AVE MADISON AVE MADISON LEXINGTON AVE LEXINGTON E 65TH ST 2 SPECIAL MADISON AVENUE PRESERVATION DISTRICT ZONING DISTRICT DECEMBER 20,1973 2ND AVE 3RD AVE 3RD PARK AVE PARK FIFTH AVE MADISON AVE MADISON LEXINGTON AVE E 75TH ST E 75TH ST E 66TH STREET E 70TH ST E 70TH ST 762 MADISON AVENUE MADISON 3RD AVE 3RD 2ND AVE PARK AVE PARK FIFTH AVE MADISON AVE MADISON LEXINGTON AVE 19 21 760 E 65TH ST E 65TH ST E 65TH STREET E 60TH ST E 60TH ST 3 UPPER EAST SIDE HISTORIC DISTRICT LANDMARK DISTRICT DESIGNATED MAY 19,1981 2ND AVE 3RD AVE 3RD PARK AVE PARK FIFTH AVE MADISON AVE MADISON LEXINGTON AVE E 75TH ST E 75TH ST E 66TH STREET E 70TH ST E 70TH ST 762 MADISON AVENUE MADISON 3RD AVE 3RD 2ND AVE PARK AVE PARK FIFTH AVE MADISON AVE MADISON LEXINGTON AVE 19 21 760 E 65TH ST E 65TH ST E 65TH STREET E 60TH ST E 60TH ST 4 MADISON AVENUE LUXURY RETAIL FIFTH MADISON PARK LEXINGTON 3RD 2ND AVE AVE AVE AVE AVE AVE MISSONI VERA WANG MISSONI CHRISTIAN LOUBOUTIN APPLE VERA WANG STELLA MCCARTNEY RALPH LAUREN CHRISTIAN LOUBOUTIN EMILIO PUCCI E 75TH ST APPLE LANVIN PRADA STELLA MCCARTNEY ANNE FONTAINE BALENCIAGA CARTIER RALPH LAUREN RALPH LAUREN DOLCE & GABBANA VALENTINO EMILIO PUCCI JIL SANDER LANVIN E 70TH ST LA PERLA BALENCIAGA PRADA GIUSEPPE ZANOTTI CARTIER ANNE FONTAINE CAROLINA HERRERA DOLCE & GABBANA JIL SANDER VALENTINO ISABEL MARANT GIUSEPPE ZANOTTI J. -

Building 'Suburban' Luxury in the Sky by ANNA BAHNEY JUNE 5, 2005

Building 'Suburban' Luxury in the Sky By ANNA BAHNEY JUNE 5, 2005 IN the last few years, Manhattanites of means have grown accustomed to having the world's most famous architects furiously catering to their every whim, trying to lure them to apartments that seem to break price records with each new building. The newest entrant is Peter Marino, best known for exquisite interiors created for fashion designers like Giorgio Armani (an apartment in Milan) and Valentino Garavani (a private yacht) and for financiers like Stephen Schwarzman (an apartment at 740 Park Avenue) and David Martinez (one home in London and another atop the Time Warner Center) as well as high-end fashion showrooms evocative of the clothes inside. Now, in his first building, Mr. Marino, 55, is designing the interiors and exteriors of a new condominium at 170 East End Avenue, between 87th and 88th Streets. The offering plan has not been approved yet, but proposed prices range from $1,600 to $3,000 a square foot -- that's at least $3.2 million for a 1,600-square-foot two-bedroom apartment. To attract buyers, the building will have to up the ante and Mr. Marino's name will undoubtedly help. Star designers and architects like Richard Meier, Charles Gwathmey, David Childs, Costas Kondylis, Cesar Pelli and Philippe Starck have each had their hand in signature buildings in Manhattan recently. But even the developer of the East End Avenue condos, Orin Wilf, does not seem entirely sure how to present the project to wealthy urban dwellers. In a meeting recently at Mr.