Building 'Suburban' Luxury in the Sky by ANNA BAHNEY JUNE 5, 2005

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

GRACIE MANSION, East End Avenue at 88Th Street in Carl Schurz Park, Borough of Manhattan

Landmarks Preservation Commission September 20, 1966, Number 1 LP-0179 GRACIE MANSION, East End Avenue at 88th Street in Carl Schurz Park, Borough of Manhattan. Begun 1799, completed 1801; north addition 1810. Landmark Site: Borough of Manhattan Tax Map Block 1592, Lot l in part, consisting of the land on which the described building is situated. On March 8, 1966, the Landmarks Preservation Commission held a public hearing on the proposed designation as a Landmark of Gracie Mansion and the proposed desig nation of the related Landmark Site. (Item No. 3). The hearing had been duly advertised in accordance with the provisions of l aw. Two witnesses spoke in favor of designation, including the Park Commissioner Thomas • Hoving. There were no speakers in opposition to designation~ DESCRIPTION AND ANALYSIS Located in Carl Schurz Park on the East River at East Eighty Eighth Street is one of the finest Federal Style country seats r emaining to us from that early period. Standing on a promontory, once known as "Gracie's Point," the large two story frame house is enclosed, at first floor l evel, by a porch surmounted by a handsome Chinese hippendale railing, a near duplicate of the balustrade surrounding the hipped roof above. On the river side the house boasts ~~ exceedingly fine Federal doorway with leaded glass sidelights and a semi-circular lunette above the door, flanked by oval rosettes set between delicate wood consoles. As tradition would have us believe, this work, consisting of additions made b,y Archibald Gracie about 1809, may well represent the efforts of the noted architect, Major Charles Pierre L'Enfant. -

15 Armani/Architecture the Timelessness and Textures of Space John Potvin

15 Armani/Architecture The Timelessness and Textures of Space John Potvin To borrow Pierre Bourdieu’s notion of “symbolic magic,” a fashion designer’s label possesses the auratic potency to conjure the mystique of distinction, authenticity, and exclusivity which in turn engenders a fervent dedication (verging on the religious) on the part of faithful costumers. The aura surround- ing the name of the designer transforms objects of no real value to objects of luxury, preciousness, and desire. However, the label itself is not enough; it requires to be housed in a space equally endowed with the potential to elicit reverence and pleasure, a coveted destination. Boutiques offer up affective spatial attenuation of the auratic nature of the designer’s label through the preferred pathways of engagement with the space and merchandise. In his discussion of retail design Otto Riewoldt contends that “[w]ith the same care and professionalism as in the theatre, the sequence of events [of shopping] must be worked out in detail, including everything from props to stage direc- tions, in order to transform the sale of merchandise into an experience-inten- sive act—one in which the potential customers are actors rather than passive spectators” (Riewoldt 9). To best achieve this, a designer must create spaces which communicate his brand, as distinct from all other designer and public spaces. As a designer attempts to make his mark, therefore, so too must he employ an architect whose own unmistakable material signature will assist in the proposition and perpetuation of an authentic designer material and visual identity. The boutique itself must be equally as visually effective and mate- rially auratic as the discreet label sewn into an Armani garment. -

Ackerman and Sonnenschein of Meridian Arrange $104

Ackerman and Sonnenschein of Meridian arrange $104 million financing; Levine & Berkes of Meridian handle $37 million: loan placed by Mesa West July 05, 2016 - Front Section Shaya Ackerman, Meridian Capital GroupShaya Sonnenschein, Meridian Capital GroupRonnie Levine, Meridian Capital Group Manhattan, NY Meridian Capital Group arranged $104 million in acquisition financing for the purchase of The Hamilton multifamily property located at 1735 York Ave. on the Upper East Side on behalf of Bonjour Capital. The seven-year loan, provided by a balance sheet lender, features a competitive fixed rate of 3.625% and three years of interest-only payments. This transaction was negotiated by Meridian managing director, Shaya Ackerman, and senior vice president, Shaya Sonnenschein. The Hamilton, 1735 York Avenue - Manhattan, NY The 38-story property totals 265 units and is located at 1735 York Avenue, on the northwest corner of East 90th Street, across the street from the Asphalt Green sports facility and along the East River Esplanade. Apartments feature granite kitchens, marble bathrooms and individually controlled air conditioning in each room. Building features include an elegant lobby with a 24-hour uniformed doorman, attended service entrance, state-of-the-art fitness center, locker rooms and saunas, landscaped roof deck, a children’s playroom, furnished lounge with kitchen, billiards lounge, fully-equipped air-conditioned laundry facility, attached 24-hour garage, building-wide water filtration and complimentary shuttlebus service to the subway and shopping. Residents enjoy close proximity to the 4 and 6 subway lines and the property’s location affords quick access to leading epicurean establishments, exclusive private and public schools, notable global cultural institutions including the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Guggenheim museum as well as Carl Schurz Park, Central Park and the shopping mecca of Madison Avenue. -

Take Advantage of Dog Park Fun That's Off the Chain(PDF)

TIPS +tails SEPTEMBER 2012 Take Advantage of Dog Park Fun That’s Off the Chain New York City’s many off-leash dog parks provide the perfect venue for a tail-wagging good time The start of fall is probably one of the most beautiful times to be outside in the City with your dog. Now that the dog days are wafting away on cooler breezes, it may be a great time to treat yourself and your pooch to a quality time dedicated to socializing, fun and freedom. Did you know New York City boasts more than 50 off-leash dog parks, each with its own charm and amenities ranging from nature trails to swimming pools? For a good time, keep this list of the top 25 handy and refer to it often. With it, you and your dog will never tire of a walk outside. 1. Carl Schurz Park Dog Run: East End Ave. between 12. Inwood Hill Park Dog Run: Dyckman St and Payson 24. Tompkins Square Park Dog Run: 1st Ave and Ave 84th and 89th St. Stroll along the East River after Ave. It’s a popular City park for both pooches and B between 7th and 10th. Soft mulch and fun times your pup mixes it up in two off-leash dog runs. pet owners, and there’s plenty of room to explore. await at this well-maintained off-leash park. 2. Central Park. Central Park is designated off-leash 13. J. Hood Wright Dog Run: Fort Washington & 25. Washington Square Park Dog Run: Washington for the hours of 9pm until 9am daily. -

Beauty Power

BEAUTY Contacts: Thea M. Page, 626-405-2260, [email protected] Lisa Blackburn, 626-405-2140, [email protected] POWER Renaissance and Baroque Bronzes & from the Peter Marino Collection PETER MARINO Peter Marino, FAIA, is the principal of Peter Marino Archi - tect PLLC, an internationally acclaimed architecture, plan - ning, and design firm founded in 1978 and based in New York City. Marino’s design contributions in the areas of commercial, cultural, residential, and retail architecture have helped redefine modern luxury, emphasizing materiality, tex - ture, scale, light, and the dialogue between interior and exte - rior. His recent architectural projects include Chanel boutiques in Los Angeles (one on Robertson Boulevard and the other on Rodeo Drive in Beverly Hills) and the Chanel Tower in Ginza, Tokyo; Louis Vuitton boutiques in Shang - hai and Singapore, and the recently opened Louis Vuitton Maison on London’s New Bond Street; a Dior boutique in Shanghai; a fine jewelry boutique in Geneva; Ermenegildo Zegna global flagship stores in Tokyo and Hong Kong; and 170 East End Avenue, a luxury, high-rise condominium on New York’s Upper East Side. Marino was born in New York City. He received an architecture degree from Cornell Univer - sity and began his career with the architecture firms Skidmore Owings & Merrill and I. M. Pei/Cossutta & Ponte. Andy Warhol and Yves Saint Laurent were among Marino’s first clients, with initial commis - sions including the design of Warhol’s seminal Factory space and renovation of his New York townhouse. Friendship with Warhol furthered Marino’s interest in art collecting, a passion he has been able to develop while sourcing artworks for clients and through his work for international museums. -

Spotlight on NYC's Athletic Fields, Bathrooms and Drinking Fountains

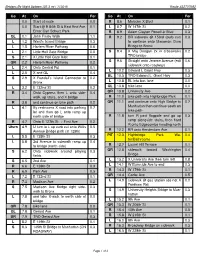

research project 111605 1/4/06 12:19 PM Page 1 The Mini Report Card on Parks Spotlight on NYC’s Athletic Fields, Bathrooms and Drinking Fountains November 2005 research project 111605 1/4/06 12:19 PM Page 2 Table of Contents 1 The Mini Report Card on Parks 2 Athletic Fields 4 Bathrooms 6 Drinking Fountains 8 Recommendations 9 Find Your Park 14 Methodology research project 111605 1/4/06 12:19 PM Page 3 Why A Mini Report Card on Parks? ince 2002, New Yorkers for Parks (NY4P) has conducted comprehensive This study has proven that the more extensive Report Card, though it only included one inspections throughout the five boroughs as part of our Report Card on Parks site visit per summer, is indeed effectively tracking neighborhood park conditions. Low Sevaluation program. The Mini Report Card on Parks, a follow-up study under- and mediocre scores for these three features covered in The Mini Report Card are not taken during the summer of 2005, focuses on athletic fields, bathrooms, and drink- anomalies or “spikes”/“dips”– they are common conditions and consistent with the three ing fountains, tracking the conditions of these features over a three-month period. previous Report Card studies. This design is meant to track maintenance for specific, heavily used features, to mon- These poor scores are the result of decades of disinvestment. Even with a recent modest itor changes over time, and to “test” past Report Card on Parks inspection ratings. increase, bipartisan cuts over the last 20 years have resulted in an almost 20% cut in the 1 The annual Report Card provides information on the following eight Major Service Parks Department’s budget and an approximately 60% cut in staffing. -

7. the Vision CIVITAS CIVITAS CIVITAS CIVITAS CIVITAS CIVITAS CIVITAS CIVITAS

CIVITAS CIVITAS CIVITAS CIVITAS CIVITAS CIVITAS CIVITAS CIVITAS CIVITAS CIVITAS CIVITAS CIVITAS CIVITAS CIVITAS CIVITAS CIVITAS CIVITAS CIVITAS CIVITAS CIVITAS CIVITAS CIVITAS CIVITAS CIVITAS 7. The Vision CIVITAS CIVITAS CIVITAS CIVITAS CIVITAS CIVITAS CIVITAS CIVITAS CIVITAS CIVITAS CIVITAS CIVITAS CIVITAS CIVITAS CIVITAS CIVITAS CIVITAS CIVITAS CIVITAS CIVITAS CIVITAS CIVITAS CIVITAS CIVITAS 80 East River Esplanade Vision Plan Site Specific Visions Through research, analysis, outreach, and as bold, playful gestures, potentially discussions with city and state agency whimsical in nature and designed to representatives, it became apparent that spark conversation about the community’s a phased, incremental approach to the desires for future design. Other short-term reconstruction of the Esplanade would be interventions simply involve removing the most feasible for this project. The technical, physical and visual “clutter” of derelict financial, and regulatory challenges suggest furnishing and dead vegetation, serving to that some long narrow segments will make circulation easier and prepare for remain as such, even if the more ambitious longer-term projects. In some locations, designs of a long-term master plan are the desired condition requires a longer implemented. However, there are clearly timeframe within which to plan, construct, opportunities to broaden the Esplanade in and secure funding. It is important to note certain locations. This would create larger that the concepts presented in this report nodes that will better serve the needs of the are a vision describing only some of the community and reconnect people to their many possible outcomes. They should waterfront. serve as an aspirational template, but not be overly prescriptive or inflexible. -

Go at on for 0.0 Start of Route 0.0 0.0 Start @ E 84Th St & East End

Bridges By Night Uptown (25.3 mi / 1130 ft) Route #32737682 Go At On For Go At On For 0.0 Start of route 0.0 R 8.6 Malcolm X Blvd 0.1 0.0 Start @ E 84th St & East End Ave. 0.1 L 8.7 W 147th St 0.2 Enter Carl Schurz Park R 8.9 Adam Clayton Powell Jr Blvd 0.3 QL 0.1 John Finley Walk 1.1 R 9.2 BR sidewalk @ 153rd (curb cut) 0.3 L 1.2 Ward’s Island Bridge 0.3 to continue onto Macombs Dam L 1.5 Harlem River Pathway 0.6 Bridge to Bronx L 2.1 Little Hell Gate Bridge 0.0 S 9.4 X Maj Deegan 2x in crosswalks 0.2 S 2.1 X Little Hell Gate Inlet 0.1 TRO bridge QR 2.2 Harlem River Pathway 0.2 S 9.6 Straight onto Jerome Avenue (exit 0.6 sidewalk onto roadway) L 2.4 Onto Central Rd 0.1 L 10.2 Edward L Grant Hwy 0.3 L 2.5 X and QL 0.4 BL 10.5 TRO Edward L. Grant Hwy 0.3 S 2.9 X Randall’s Island Connector to 0.2 Bronx L 10.8 BL into bus lane 0.0 L 3.2 E 132nd St 0.2 QL 10.8 bike lane 0.0 R 3.4 Onto Cypress then L onto side- 0.4 QR 10.8 University Ave 0.2 walk, up stairs, and X bridge R 11.0 bike path into Highbridge Park 0.1 R 3.8 and continue on bike path 0.2 QR 11.1 and continue onto High Bridge to 0.7 L 4.1 By restrooms X road into parking 0.7 Manhattan then continue south on lot and then go L onto ramp up bike path north side of bridge R 11.8 turn R past flagpole and go up 0.3 R 4.7 Onto E 127th St First Ave 0.2 ramp alongside stairs, then hard ) R onto Edgecombe heading north Uturn 4.9 U turn to L up curb cut onto Willis 0.5 Avenue Bridge path (at 125th) R 12.2 BR onto Amsterdam Ave 0.1 L 5.5 E 135th St 0.3 PIT 12.3 Highbridge Park Wa- 0.4 ter/Bathrooms -

University of Huddersfield Repository

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Huddersfield Repository University of Huddersfield Repository Anderson, Stacy, Nobbs, Karinna, Wigley, Stephen M. and Larsen, Ewa Collaborative Space: An Exploration of the Form and Function of Fashion Designer and Architect Partnerships Original Citation Anderson, Stacy, Nobbs, Karinna, Wigley, Stephen M. and Larsen, Ewa (2010) Collaborative Space: An Exploration of the Form and Function of Fashion Designer and Architect Partnerships. SCAN Journal of Media Arts Culture, 7 (2). ISSN 1449-1818 This version is available at http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/11458/ The University Repository is a digital collection of the research output of the University, available on Open Access. Copyright and Moral Rights for the items on this site are retained by the individual author and/or other copyright owners. Users may access full items free of charge; copies of full text items generally can be reproduced, displayed or performed and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided: • The authors, title and full bibliographic details is credited in any copy; • A hyperlink and/or URL is included for the original metadata page; and • The content is not changed in any way. For more information, including our policy and submission procedure, please contact the Repository Team at: [email protected]. http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/ :: SCAN | journal of media arts culture :: Page 1 of 8 Home News & Events Journal Magazine Gallery About Search >> Go Collaborative Space: An Exploration of the Form and Function of Fashion Designer and Synopsis Architect Partnerships Refereed articles Stacy Anderson, Karinna Nobbs, Stephen M. -

Making the Most of Our Parks

Making the Most of Our Parks RECREATION EXERCISE RESPITE PLAY ENSURING GREENER, SAFER, CLEANER PARKS, TOGETHER A SUMMARY OF A REPORT BY THE CITIZENS BUDGET COMMISSION AT THE REQUEST OF NEW YORKERS FOR PARKS NEW YORK’S NONPARTISAN VOICE SEPTEMBER 2007 FOR EFFECTIVE GOVERNMENT MAKING THE MOST OF OUR PARKS the challenge to new yorkers Parks play important roles in city life. They are a source of respite from the bustle of the urban environment, a place for active recreation and exercise for adults, and a safe place for children to play outdoors. In addition, parks preserve sensitive environmen- tal areas, and, by making neighborhoods more attractive, enhance property values and the tax base of the city. Given the benefits of urban parks, it should be reassuring to New Yorkers that more than 37,000 acres, or nearly one-fifth the city’s total land area, is parkland. This pro- portion is larger than in most big cities in the United States, suggesting that New Yorkers are well endowed with parks. But New Yorkers face a distinct challenge in enjoying their parks. Their parks must accommodate an unparalleled volume of people. New York has about 217 residents for each acre of parkland, one of the highest ratios in the nation, compared to a national average among large cities of about 55 residents per acre. When the extraordinarily large number of commuters and tourists is added to New York’s resident population, the potential demand on local parks likely is greater than in any other American city. New Yorkers must be especially innovative in order to make the most of their parks. -

Parks Post Nov./Dec

Manhattan PARKS POST Nov./Dec. 2007 City of New York • Parks & Recreation Michael R. Bloomberg, Mayor • Adrian Benepe, Commissioner Borough Beat Photo of the Month Riverside Alive! During October, Parks & Recreation and the Riverside Park Fund celebrated Riverside Alive!, a festival fea- turing free community events celebrating Riverside Park’s 1937 expansion under Parks Commissioner Robert Moses. Events included a groundbreaking at Soldiers and Sailors Monument Plaza, the open- ing of Serpentine Promenade, and Mayor Bloomberg breaking ground on construction of the park’s crucial waterfront greenway link, the Riverwalk. Opened in 1880, Riverside Park was significantly expanded and improved in the 1930s, growing by 132 acres. By 1937, it featured new playgrounds, promenades, and athletic facilities as well as the rotunda and the 79th Street Boat Basin. See you in the parks! Adrian Benepe, Commissioner Big Bird joined the festivities in the Bronx as Bette Midler and Bill Castro, Mayor Bloomberg plant Tree #1 to kick off Million Trees NYC. Manhattan Commissioner Photo: Daniel Avila Citywide Spotlight Something big is taking root… On October 9, Mayor Michael R. Bloomberg and New York Restoration HOW CAN I HELP? Project Founder Bette Midler planted Tree #1 in the Morrisania section of the Bronx to launch Million Trees NYC, a citywide, public-private • PLANT a tree in your yard or request a free initiative with an ambitious goal: to plant and care for one million new street tree from the Parks Department. trees across the city’s five boroughs over the next decade. • PROTECT and PRESERVE by volunteering to plant or care for trees. -

+ Public Art Tour

Corlears Hook Corlears J a c k s o n S t r e e PUBLIC ART TOUR t e o r n o M + Park Fish lton lton Hami E 10th St. St. 10th E E 6th St. E 14th St. 14th E E Houston St. St. Houston E Park Thomas Jefferson Jefferson Thomas Carl Schurz Park Schurz Carl a nel z la d d n a l l un P T Ho k r a P Seward Park Tompkins Square Tompkins E 20th St. 20th E St. Canal E 72nd St. St. 72nd E E 56th 56th E E 61st 61st E ASTOR PL. REST STOP Park Roosevelt D. Sara FOLEY SQ. REST STOP Square Chatham E 51st St. St. 51st E UPTOWN REST STOP St. 42nd E Park 52nd St. & Park Ave. Astor Pl. & Lafayette Square St.Stuyvesant Duane St. & Centre St. 35 39 36 Street Lafayette Square 8 Foley 4 Park 34 40 41 42 43 2 Gramercy LAFAYETTE ST. BROADWAY 37 44 45 46 47 48 PARK ROW 6 9 11 12 13 14 16 17 18 19 26 32 PARK AVE. PARK AVE. Park Square Union BROADWAY 49 50 51 52 5 7 27 28 10 20 29 30 31 38 Park Battery 21 22 23 E 51st St. St. 51st E E 61st St. St. 61st E 3 St. 34th E E 56th St. St. 56th E 24 25 E 42nd St. St. 42nd E E 14th St. 14th E 1 St. 20th E SOHO REST STOP Bryant Park Bryant Rotary St. John's John's St.