Performing Fabulous Monsters: Re-Inventing the Gothic Personae in Bizarre Magic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pressive Cast of Thinkers and Performers

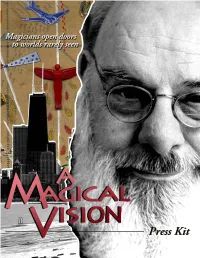

Table of Contents Long Synopsis Short Synopsis Michael Caplan Biography Key Production Personnel Filmography Credit List Magicians & Scholars Cover design by Lara Marsh, Illustration by Michael Pajon A Magical Vision /Long Synopsis ______________________________________________________ A Magical Vision spotlights Eugene Burger, a far-sighted philosopher and magician who is considered one of the great teachers of the magical arts. Eugene has spent twenty-five years speaking to magicians, academics, and the general public about the experience of magic. Advocating a return to magic’s shamanistic, healing traditions, Eugene’s “magic tricks” seek to evoke feelings of awe and transcendence, and surpass the Las Vegas-style entertainment so many of us visualize when we think of magicians. Mentors and colleagues have emerged throughout Eugene’s globe-trotting career. Among them is Jeff McBride, a recognized innovator of contemporary magic, and Max Maven, a one-man-show who performs a unique brand of “mind magic” to audiences worldwide. Lawrence Hass created the world’s first magic program in a liberal arts setting, where his seminar has attracted an impressive cast of thinkers and performers. The film, however, is Eugene’s journey. It began in 1940s Chicago, a city already renowned as the center of classic magic performance. Yale Divinity School followed, leading Eugene to the world of Asian mysticism. From there came the creation of Hauntings, a tribute to the sprit theatre of the 19th century, and the gore of the Bizarre Magick movement. Today Eugene’s performances and lectures draw inspiration from the mythology of India to the Buddhism of magical theory. On this stage, the magicians and thinkers open doors to an astounding world, a world that we rarely take time to see. -

Eugene Burger (1939-2017)

1 Eugene Burger (1939-2017) Photo: Michael Caplan A Celebration of Life and Legacy by Lawrence Hass, Ph.D. August 19, 2017 (This obituary was written at the request of Eugene Burger’s Estate. A shortened version of it appeared in Genii: The International Conjurors’ Magazine, October 2017, pages 79-86.) “Be an example to the world, ever true and unwavering. Then return to the infinite.” —Lao Tsu, Tao Te Ching, 28 How can I say goodbye to my dear friend Eugene Burger? How can we say goodbye to him? Eugene was beloved by nearly every magician in the world, and the outpouring of love, appreciation, and sadness since his death in Chicago on August 8, 2017, has been astonishing. The magic world grieves because we have lost a giant in our field, a genuine master: a supremely gifted performer, writer, philosopher, and teacher of magic. But we have lost something more: an extremely rare soul who inspired us to join him in elevating the art of magic. 2 There are not enough words for this remarkable man—will never be enough words. Eugene is, as he always said about his beloved art, inexhaustible. Yet the news of his death has brought, from every corner of the world, testimonies, eulogies, songs of praise, cries of lamentation, performances in his honor, expressions of love, photos, videos, and remembrances. All of it widens our perspective on the man; it has been beautiful and deeply moving. Even so, I have been asked by Eugene’s executors to write his obituary, a statement of his history, and I am deeply honored to do so. -

September/October 2020 Oakland Magic Circle Newsletter Official Website: Facebook:

September/October 2020 Oakland Magic Circle Newsletter Official Website:www.OaklandMagicCircle.com Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/groups/42889493580/ Password: EWeiss This Month’s Contents -. Where Are We?- page 1 - Ran’D Shines at September Lecture- page 2 - October 6 Meeting-Halloween Special -page 4 - September Performances- page 5 - Ran’D Answers Five Questions- page 9 - Phil Ackerly’s New Book & Max Malini at OMC- page 10 - Magical Resource of the Month -Black Magician Matter II-page 12 -The Funnies- page 16 - Magic in the Bay Area- Virtual Shows & Lectures – page 17 - Beyond the Bay Shows, Seminars, Lectures & Events in July- page 25 - Northern California Magic Dealers - page 32 Everything that is highlighted in blue in this newsletter should be a link that takes you to that person, place or event. WHERE ARE WE? JOIN THE OAKLAND MAGIC CIRCLE---OR RENEW OMC has been around since 1925, the oldest continuously running independent magic club west of the Mississippi. Dozens of members have gone on to fame and fortune in the magic world. When we can return to in-person meetings it will be at Bjornson Hall with a stage, curtains, lighting and our excellent new sound system. The expanding library of books, lecture notes and DVDs will reopen. And we will have our monthly meetings, banquets, contests, lectures, teach-ins plus the annual Magic Flea Market & Auction. Good fellowship is something we all miss. Until then we are proud to be presenting a series of top quality virtual lectures. A benefit of doing virtual events is that we can have talent from all over the planet and the audiences are not limited to those who can drive to Oakland. -

Shell Game a Monthly Newsletter for the London Magic Community September 2017 Volume 13, Issue 1

2017/2018 Club Membership Dues are now due!! Please bring your $40 membership renewal dues to the September meeting, or mail them to: Mark Hogan, 21-455 Hyde Park Road, London ON N6H 3R9 Shell Game A Monthly Newsletter for the London Magic Community September 2017 Volume 13, Issue 1 June’s meeting We started the summer with a bang by seeing the premiere of The Charming Cheat – Mike Fisher’s entry into this year’s London Fringe Festival. Dressed in his impressive Victorian-era suit, wearing his equally impressive handlebar mustache, the Charming Cheat opened his jacket to show the … ummm … quality items he had for sale. With no takers, he started into his games of chance. First up was a selection of 6 wallets by the audience, leading to a classic Banknite effect where Mike ended up with the $100. Next was a Three Card Monte (Martin Lewis’s Sidewalk Shuffle), and a nice Hanky to Egg routine, which he then explained to the crowd, except the hollow egg turned into a real egg! Then it was time for his Liar’s Dice routine where he determined the correct spots on the die even with it covered up (with an audience member who tried their very best to hide it!). and Cheater’s Poker was hit, where every hand the spectator dealt to our Charming Cheat was the winner! He also performed a rope escape from behind his suit jacket. Finally he got the 6 spectators with wallets to come up on stage. A pre- written set of instructions were used to eliminate them one by one until only one remained. -

THE MAGIC LAWYER® When Law Meets Magic

THE MAGIC LAWYER® When Law Meets Magic By Robert Speer, The Magic Lawyer® Copyright © 2009 Robert H. Speer, Jr., The Magic Lawyer® All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, without the prior written permission of the author. INTRODUCTION "It’s kind of fun to do the impossible." -- Walt Disney Just who and what is The Magic Lawyer®1? I’m asked that question quite a bit. It is a persona, a brand, and a real person, all in one. It is what happened when law mixed with magic. It is what a perfect stranger remembers when they see my card in their wallet months after we met. It is the hope that my clients have that, no matter how bad their situation is, they know that their lawyer is doing his best “magic” for them in court. It represents a refreshing way to practice law - - a way that reminds the client that life can be fun, no matter what happened to them, or why they are in their current situation. It is also a really cool way to market Robert Speer, Attorney at Law. When I was about ten years old, my dad let me travel with him when he made his sales calls around the southeast. On our travels, we would always look forward to stopping at one of the Stuckey’s gas stations along the road. Stuckey’s gas stations are long gone, but my memory of them, and my dad, are not. In Stuckey’s, you could always find a rack of tricks and pranks made by the S.S. -

Fall Magic Auction

Public Auction #027 Fall Magic Auction Featuring Personal Artifacts and Memorabilia From The Career of Channing Pollock and The Library of James B. Alfredson Complemented by a Selection of Collectible Magicana Auction Saturday, November 1, 2014 v 10:00 Am Exhibition October 29 - 31 v 10:00 am - 5:00 pm Inquiries [email protected] Phone: 773-472-1442 Potter & Potter Auctions, Inc. 3759 N. Ravenswood Ave. -Suite 121- Chicago, IL 60613 Channing Pollock Channing West Pollock (1926 – 2006) was one of the most Snow-white birds materialized from the hands of the tall, dark, sophisticated, professional, accomplished—and imitated— and handsome magician. Then they vanished, along with the magicians of his generation. cage that held them. He began studying magic at the age of 21. Upon Pollock’s popularity was not only derived from his sleight of graduation from the Chavez College of Manual Dexterity hand technique, however. Often billed as “the most handsome and Prestidigitation in 1952, he was regarded as its most man in the world,” his appeal to general audiences led him into accomplished pupil and soon held a teaching position at starring roles in European films such as Judex and Rocambole, the school, but quickly moved on to a storied career in show and to regular appearances in American television on a number business. In 1954, he appeared on Ed Sullivan’s famous of popular programs. television variety show. Soon thereafter, Pollock went on to Although Pollock retired from show business completely conquer American stages, and then set his sights abroad to in 1969, he never lost his love for magic. -

Download Press

Press Resource Contents: page Why McBride? 1 The Shows 2 Bio. 3 Clients/ Awars 4 Magic Magazine Article 5-12 Reviews 12-21 JeffJeff McBrideMcBride Why McBride Magic is the perfect show for your showroom or event 1. If you want appreciative, excited audiences, McBride’s shows have a proven record for thrill- ing audiences and reviewers worldwide. 2. Do you have a mixed audience of different ages, or different cultures? McBride’s magic appeals to audiences of all types and nationalities. The show is a visual and aural spectacle which can be fully understood no matter what the viewer’s native language. 3. Looking for a way to generate publicity for your event or product? We have long experience working with our clients’ creative and marketing staffs to assure the show will meet your criteria for success on every level. 4. We have a time-tested set of technical requirements which we can tailor to your venue and situa- tion. Because we have performed in every kind of venue imaginable, we know how to get the most from whatever technical support you can provide, and to work well with your technical staff. 5. When budgets are tight, but you need to make a big splash, our small company (McBride, 1-5 Assistants, one Production Manager) puts on a very big show -- the most exciting magic show in all the world! We have shows of different sizes to fit any budget and space. 6. We enjoy doing community outreach types of promotion - appearances at local schools, fund-rais- ers, etc., that help you both to sell tickets and maintain good relations for your organization within the community. -

[email protected]

[email protected] Sherman, Texas ‐ Lawrence Hass is professor of humanities at Austin College. He also has an international reputation as a sleight of hand magician and holds the position of associate dean of Jeff McBride’s Magic & Mystery School in Las Vegas. Dr. Hass came to Austin College in July of 2009 when his wife Dr. Marjorie Hass became the College’s 15th president. Prior to this, he was professor of philosophy and theatre arts at Muhlenberg College in Allentown, Pennsylvania, where he was an award‐winning teacher of philosophy and theatre, specializing in phenomenology, aesthetics, magic performance, and the history and philosophy of magic. During his 18‐year tenure at Muhlenberg College, Dr. Hass founded and directed the “Theory and Art of Magic” program—a college‐level co‐curricular program that was dedicated to the study and appreciation of the magical arts. From 1999 to 2009, the “Theory and Art of Magic” program featured performances, talks, and lectures by such world‐leading stars of magic as David Blaine, Eugene Burger, Roberto Giobbi, Max Howard, René Lavand, Max Maven, Jeff McBride, Robert E. Neale, Jim Steinmeyer, Juan Tamariz, and Teller (among many others). By the end of its 11‐year run, the “Theory and Art of Magic” program was drawing attendees—magicians, students, and scholars of magic—from all over the country and internationally. As an outgrowth of the program, Dr. Hass founded Theory and Art of Magic Press in 2007 to publish books, DVDs, and other materials that would connect with people wanting to perform and think about magic in a deeper way. -

Eliciting Wonder and Analyzing Its Expression Seth Taylor Raphaël

The Wonder of Magic: Eliciting Wonder and Analyzing its Expression by Seth Taylor Rapha¨el B.A., Hampshire College (2004) Submitted to the Program in Media Arts and Sciences, School of Architecture and Planning, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Media Arts and Sciences at the MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY September 2007 c Massachusetts Institute of Technology 2007. All rights reserved. Author Program in Media Arts and Sciences August 10, 2007 Certified by Rosalind W. Picard Professor of Media Arts and Sciences Program in Media Arts and Sciences Thesis Supervisor Accepted by Prof. Deb Roy Chairperson, Departmental Committee on Graduate Students Program in Media Arts and Sciences 2 The Wonder of Magic: Eliciting Wonder and Analyzing its Expression by Seth Taylor Rapha¨el Submitted to the Program in Media Arts and Sciences, School of Architecture and Planning, on August 10, 2007, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Media Arts and Sciences Abstract Insert abstract here. Thesis Supervisor: Rosalind W. Picard Title: Professor of Media Arts and Sciences, Program in Media Arts and Sciences 3 4 The Wonder of Magic: Eliciting Wonder and Analyzing its Expression by Seth Taylor Rapha¨el The following people served as readers for this thesis: Thesis Reader Glorianna Davenport Professor of Media Arts and Sciences Program in Media Arts and Sciences Thesis Reader Nick Pudar Vice President of Planning and Business Development OnStar 5 6 Contents Abstract 3 I Forematter 10 1 Acknowledgements 13 2 Preface 15 II The Study 17 3 Effect 19 3.1 Definition of Wonder . -

Title Subtitle Featuring 1 World Renowned Magic of Paul Potassy

# Title Subtitle Featuring 1 World Renowned Magic of Paul Potassy World Renowned Magic of Paul Potassy Potassy; Paul 2 T & R Tissue T & R Tissue White; Bob 3 Card Magic A Practical Approach White; Bob 4 Classic Six Card Repeat Greater Magic Video Library Various 5 Banachek's Psi Series Mentalism for the casual performer; part 1 Banachek 6 Banachek's Psi Series Mentalism for the casual performer; part 2 Banachek 7 Banachek's Psi Series Psychophysiological Thought (muscle) Reading Banachek 8 Banachek's Psi Series Psychokinesis Banachek 9 Masters of Mental Magic Falkenstein & Willard Falkenstein & Willard 10 Masters of Mental Magic Falkenstein & Willard Falkenstein & Willard 11 Masters of Mental Magic Falkenstein & Willard Falkenstein & Willard 12 In Action Gregory Wilson Wilson 13 In Action Gregory Wilson Wilson 14 In Action Gregory Wilson Wilson 15 Here I Go Again Bill Malone Malone 16 Here I Go Again Bill Malone Malone 17 Here I Go Again Bill Malone Malone 18 Educating Archer John Archer Archer; John 19 Magic You Can Make Magic Makers Presents Grams; Martin 20 Strengthening Your Magic Mike Powers Lecture CD Powers; Mike 21 Professional Rope Routines World's Greatest Magic Various 22 Cups & Balls Magic Makers Presents Ray; Eddie 23 Card Trick Magic Expert Insight Vanel; Stephane 24 Outstanding Magic Magic for Stand-up Performers Colombini; Aldo 25 Roped In Rope routines Colombini; Aldo 26 Card Capers Easy Card Routines Colombini; Aldo 27 All Hands on Deck Ten Card Routines Colombini; Aldo 28 Learn Magic w/ Timothy Noonan Novelty Magic Noonan; -

My Magic Ebook Collection

Magician books Aaron Fisher The Paper Engine FISM 2003 The Graduate Genii article 2009 Aaron Shields Dribble Block Pass Al Koran Legacy Professonal Presentations Alex Elmsley Collected works vol 1-2 Allan Ackerman Las Vegas Kardma 2004 lecture notes classic handlings here's my card the cardjuror 2012 notes Andi Gladwin The Cheetah's Handbook1-2 Andrew Wimhurst Down Under Deal Andy Nyman Bulletproof Annemann Practical Mental Magic The Jinx the life and times of a legend Anthony black Acaan Emote OOBE Resurrection dreams The sight of madness Antinomy 2005, 2006 Arthur Buckley Card control Improved and original card problems Asi Wind Chapter One Arturo de Ascano The magic of Ascanio vol 1-3 Atlas Brooking The prodigal the crusade Banachek Pyschological Subleties 1-3 Psychological Thought Reading Benjamin Earl Past midnight Bonus Booklet Dr Strangehand How to fool a Physicist Gambit 1&2 Bert Allerton The Close Up Magician Bill Cushman The Dr's Billet Tear Bill Dekel direct Mindcrafts psionics, visions Air Writer Digit Bill Goodwin Penumbra 1-11 lecture 1988 notes from the batcave the ancient empty street (1997) Evolution(2011) At the expense of grey matter Mini Lecture SAM 1994 Picking the carcas clean Theatricks Bill Montana psychic motherfucker Bill Simon Effective Card Magic bobo Modern Coin Magic Boris Wild ACAAB Brandon Queen Phatom Bruce Cervon Lecture notes 1995 card secrets Hard boiled mysteries Ultra Cervon Bryn reynolds the logar scrolls bullfrog issue 0-2 Caleb Wiles High Spots Cameron Francis Aberrations Convergence Everywhere -

Tommy Wonder & Stephen Minch)

Downloaded from www.vanishingincmagic.com by Ray Hyman EDITED by Joshua Jay Cover designed by Vinny DePonto Layout by Andi Gladwin Downloaded from www.vanishingincmagic.com by Ray Hyman Magic in Mind was prepared in cooperation with the Society of American Magicians, and the ebook will be made available for free to all members worldwide. www.vanishingincmagic.com All rights reserved. The essays in this book are copyrighted by their respective authors and used with permission. No portion may be reproduced without written permission from the authors. Downloaded from www.vanishingincmagic.com by Ray Hyman AcknowledgEments Magic in Mind started out as a project intended expressly for serious young magicians, but the first of many lessons I learned during my two-year endeavor is this: age has little to do with learning. It was evident, early on, that this collection would benefitanyone serious about getting serious in magic. So here we are. Thanks to all the generous magicians who have allowed me to include their work in this collection. I am overwhelmed by the support they have shown. In particular, I wish to single out Darwin Ortiz, whose writings I admire greatly, and who went against a personal policy, and agreed to participate. I consider it a favor to me, and a favor to all those who will learn from his writings. Thanks, Darwin, for being flexible and generous. Thanks to Stephen Minch, whose encouragement and “pull” helped initiate the project. Irving Quant helped with the translation of “Fundamentals of Illusionism” by Juan Tamariz. Denis Behr suggested a few essays I was not familiar with.