Kilkhampton, Cornwall Andrew Breeze

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Parish Boundaries

Parishes affected by registered Common Land: May 2014 94 No. Name No. Name No. Name No. Name No. Name 1 Advent 65 Lansall os 129 St. Allen 169 St. Martin-in-Meneage 201 Trewen 54 2 A ltarnun 66 Lanteglos 130 St. Anthony-in-Meneage 170 St. Mellion 202 Truro 3 Antony 67 Launce lls 131 St. Austell 171 St. Merryn 203 Tywardreath and Par 4 Blisland 68 Launceston 132 St. Austell Bay 172 St. Mewan 204 Veryan 11 67 5 Boconnoc 69 Lawhitton Rural 133 St. Blaise 173 St. M ichael Caerhays 205 Wadebridge 6 Bodmi n 70 Lesnewth 134 St. Breock 174 St. Michael Penkevil 206 Warbstow 7 Botusfleming 71 Lewannick 135 St. Breward 175 St. Michael's Mount 207 Warleggan 84 8 Boyton 72 Lezant 136 St. Buryan 176 St. Minver Highlands 208 Week St. Mary 9 Breage 73 Linkinhorne 137 St. C leer 177 St. Minver Lowlands 209 Wendron 115 10 Broadoak 74 Liskeard 138 St. Clement 178 St. Neot 210 Werrington 211 208 100 11 Bude-Stratton 75 Looe 139 St. Clether 179 St. Newlyn East 211 Whitstone 151 12 Budock 76 Lostwithiel 140 St. Columb Major 180 St. Pinnock 212 Withiel 51 13 Callington 77 Ludgvan 141 St. Day 181 St. Sampson 213 Zennor 14 Ca lstock 78 Luxul yan 142 St. Dennis 182 St. Stephen-in-Brannel 160 101 8 206 99 15 Camborne 79 Mabe 143 St. Dominic 183 St. Stephens By Launceston Rural 70 196 16 Camel ford 80 Madron 144 St. Endellion 184 St. Teath 199 210 197 198 17 Card inham 81 Maker-wi th-Rame 145 St. -

Wind Turbines East Cornwall

Eastern operational turbines Planning ref. no. Description Capacity (KW) Scale Postcode PA12/02907 St Breock Wind Farm, Wadebridge (5 X 2.5MW) 12500 Large PL27 6EX E1/2008/00638 Dell Farm, Delabole (4 X 2.25MW) 9000 Large PL33 9BZ E1/90/2595 Cold Northcott Farm, St Clether (23 x 280kw) 6600 Large PL15 8PR E1/98/1286 Bears Down (9 x 600 kw) (see also Central) 5400 Large PL27 7TA E1/2004/02831 Crimp, Morwenstow (3 x 1.3 MW) 3900 Large EX23 9PB E2/08/00329/FUL Redland Higher Down, Pensilva, Liskeard 1300 Large PL14 5RG E1/2008/01702 Land NNE of Otterham Down Farm, Marshgate, Camelford 800 Large PL32 9SW PA12/05289 Ivleaf Farm, Ivyleaf Hill, Bude 660 Large EX23 9LD PA13/08865 Land east of Dilland Farm, Whitstone 500 Industrial EX22 6TD PA12/11125 Bennacott Farm, Boyton, Launceston 500 Industrial PL15 8NR PA12/02928 Menwenicke Barton, Launceston 500 Industrial PL15 8PF PA12/01671 Storm, Pennygillam Industrial Estate, Launceston 500 Industrial PL15 7ED PA12/12067 Land east of Hurdon Road, Launceston 500 Industrial PL15 9DA PA13/03342 Trethorne Leisure Park, Kennards House 500 Industrial PL15 8QE PA12/09666 Land south of Papillion, South Petherwin 500 Industrial PL15 7EZ PA12/00649 Trevozah Cross, South Petherwin 500 Industrial PL15 9LT PA13/03604 Land north of Treguddick Farm, South Petherwin 500 Industrial PL15 7JN PA13/07962 Land northwest of Bottonett Farm, Trebullett, Launceston 500 Industrial PL15 9QF PA12/09171 Blackaton, Lewannick, Launceston 500 Industrial PL15 7QS PA12/04542 Oak House, Trethawle, Horningtops, Liskeard 500 Industrial -

1860 Cornwall Quarter Sessions and Assizes

1860 Cornwall Quarter Sessions and Assizes Table of Contents 1. Epiphany Sessions .......................................................................................................... 1 2. Lent Assizes .................................................................................................................. 19 3. Easter Sessions ............................................................................................................. 64 4. Midsummer Sessions ................................................................................................... 79 5. Summer Assizes ......................................................................................................... 102 6. Michaelmas Sessions.................................................................................................. 125 Royal Cornwall Gazette 6th January 1860 1. Epiphany Sessions These Sessions opened at 11 o’clock on Tuesday the 3rd instant, at the County Hall, Bodmin, before the following Magistrates: Chairmen: J. JOPE ROGERS, ESQ., (presiding); SIR COLMAN RASHLEIGH, Bart.; C.B. GRAVES SAWLE, Esq. Lord Vivian. Edwin Ley, Esq. Lord Valletort, M.P. T.S. Bolitho, Esq. The Hon. Captain Vivian. W. Horton Davey, Esq. T.J. Agar Robartes, Esq., M.P. Stephen Nowell Usticke, Esq. N. Kendall, Esq., M.P. F.M. Williams, Esq. R. Davey, Esq., M.P. George Williams, Esq. J. St. Aubyn, Esq., M.P. R. Gould Lakes, Esq. W.H. Pole Carew, Esq. C.A. Reynolds, Esq. F. Rodd, Esq. H. Thomson, Esq. Augustus Coryton, Esq. Neville Norway, Esq. Harry Reginald -

Cornwall Council Altarnun Parish Council

CORNWALL COUNCIL THURSDAY, 4 MAY 2017 The following is a statement as to the persons nominated for election as Councillor for the ALTARNUN PARISH COUNCIL STATEMENT AS TO PERSONS NOMINATED The following persons have been nominated: Decision of the Surname Other Names Home Address Description (if any) Returning Officer Baker-Pannell Lisa Olwen Sun Briar Treween Altarnun Launceston PL15 7RD Bloomfield Chris Ipc Altarnun Launceston Cornwall PL15 7SA Branch Debra Ann 3 Penpont View Fivelanes Launceston Cornwall PL15 7RY Dowler Craig Nicholas Rivendale Altarnun Launceston PL15 7SA Hoskin Tom The Bungalow Trewint Marsh Launceston Cornwall PL15 7TF Jasper Ronald Neil Kernyk Park Car Mechanic Tredaule Altarnun Launceston Cornwall PL15 7RW KATE KENNALLY Dated: Wednesday, 05 April, 2017 RETURNING OFFICER Printed and Published by the RETURNING OFFICER, CORNWALL COUNCIL, COUNCIL OFFICES, 39 PENWINNICK ROAD, ST AUSTELL, PL25 5DR CORNWALL COUNCIL THURSDAY, 4 MAY 2017 The following is a statement as to the persons nominated for election as Councillor for the ALTARNUN PARISH COUNCIL STATEMENT AS TO PERSONS NOMINATED The following persons have been nominated: Decision of the Surname Other Names Home Address Description (if any) Returning Officer Kendall Jason John Harrowbridge Hill Farm Commonmoor Liskeard PL14 6SD May Rosalyn 39 Penpont View Labour Party Five Lanes Altarnun Launceston Cornwall PL15 7RY McCallum Marion St Nonna's View St Nonna's Close Altarnun PL15 7RT Richards Catherine Mary Penpont House Altarnun Launceston Cornwall PL15 7SJ Smith Wes Laskeys Caravan Farmer Trewint Launceston Cornwall PL15 7TG The persons opposite whose names no entry is made in the last column have been and stand validly nominated. -

CORNWALL Extracted from the Database of the Milestone Society

Entries in red - require a photograph CORNWALL Extracted from the database of the Milestone Society National ID Grid Reference Road No Parish Location Position CW_BFST16 SS 26245 16619 A39 MORWENSTOW Woolley, just S of Bradworthy turn low down on verge between two turns of staggered crossroads CW_BFST17 SS 25545 15308 A39 MORWENSTOW Crimp just S of staggered crossroads, against a low Cornish hedge CW_BFST18 SS 25687 13762 A39 KILKHAMPTON N of Stursdon Cross set back against Cornish hedge CW_BFST19 SS 26016 12222 A39 KILKHAMPTON Taylors Cross, N of Kilkhampton in lay-by in front of bungalow CW_BFST20 SS 25072 10944 A39 KILKHAMPTON just S of 30mph sign in bank, in front of modern house CW_BFST21 SS 24287 09609 A39 KILKHAMPTON Barnacott, lay-by (the old road) leaning to left at 45 degrees CW_BFST22 SS 23641 08203 UC road STRATTON Bush, cutting on old road over Hunthill set into bank on climb CW_BLBM02 SX 10301 70462 A30 CARDINHAM Cardinham Downs, Blisland jct, eastbound carriageway on the verge CW_BMBL02 SX 09143 69785 UC road HELLAND Racecourse Downs, S of Norton Cottage drive on opp side on bank CW_BMBL03 SX 08838 71505 UC road HELLAND Coldrenick, on bank in front of ditch difficult to read, no paint CW_BMBL04 SX 08963 72960 UC road BLISLAND opp. Tresarrett hamlet sign against bank. Covered in ivy (2003) CW_BMCM03 SX 04657 70474 B3266 EGLOSHAYLE 100m N of Higher Lodge on bend, in bank CW_BMCM04 SX 05520 71655 B3266 ST MABYN Hellandbridge turning on the verge by sign CW_BMCM06 SX 06595 74538 B3266 ST TUDY 210 m SW of Bravery on the verge CW_BMCM06b SX 06478 74707 UC road ST TUDY Tresquare, 220m W of Bravery, on climb, S of bend and T junction on the verge CW_BMCM07 SX 0727 7592 B3266 ST TUDY on crossroads near Tregooden; 400m NE of Tregooden opp. -

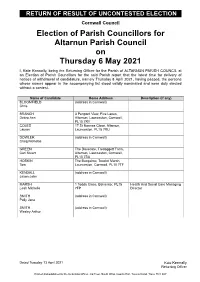

Election of Parish Councillors for Altarnun Parish Council on Thursday 6 May 2021

RETURN OF RESULT OF UNCONTESTED ELECTION Cornwall Council Election of Parish Councillors for Altarnun Parish Council on Thursday 6 May 2021 I, Kate Kennally, being the Returning Officer for the Parish of ALTARNUN PARISH COUNCIL at an Election of Parish Councillors for the said Parish report that the latest time for delivery of notices of withdrawal of candidature, namely Thursday 8 April 2021, having passed, the persons whose names appear in the accompanying list stood validly nominated and were duly elected without a contest. Name of Candidate Home Address Description (if any) BLOOMFIELD (address in Cornwall) Chris BRANCH 3 Penpont View, Five Lanes, Debra Ann Altarnun, Launceston, Cornwall, PL15 7RY COLES 17 St Nonnas Close, Altarnun, Lauren Launceston, PL15 7RU DOWLER (address in Cornwall) Craig Nicholas GREEN The Dovecote, Tredoggett Farm, Carl Stuart Altarnun, Launceston, Cornwall, PL15 7SA HOSKIN The Bungalow, Trewint Marsh, Tom Launceston, Cornwall, PL15 7TF KENDALL (address in Cornwall) Jason John MARSH 1 Todda Close, Bolventor, PL15 Health And Social Care Managing Leah Michelle 7FP Director SMITH (address in Cornwall) Polly Jane SMITH (address in Cornwall) Wesley Arthur Dated Tuesday 13 April 2021 Kate Kennally Returning Officer Printed and published by the Returning Officer, 3rd Floor, South Wing, County Hall, Treyew Road, Truro, TR1 3AY RETURN OF RESULT OF UNCONTESTED ELECTION Cornwall Council Election of Parish Councillors for Antony Parish Council on Thursday 6 May 2021 I, Kate Kennally, being the Returning Officer for the Parish of ANTONY PARISH COUNCIL at an Election of Parish Councillors for the said Parish report that the latest time for delivery of notices of withdrawal of candidature, namely Thursday 8 April 2021, having passed, the persons whose names appear in the accompanying list stood validly nominated and were duly elected without a contest. -

Clive D. Field, Bibliography of Methodist Historical Literature

Supplement to the Proceedings of the Wesley Historical Society, May 2007 BIBLIOGRAPHY OF METHODIST HISTORICAL LITERATURE THIRTY.. THIRD EDITION 2006 CLIVE D. FIELD, M.A., D.Phil., D.Litt., F.R.Hist.S. 35 Elvetham Road, Edgbaston, Birmingham B 15 2LZ [email protected] 78 PROCEEDINGS OF THE WESLEY HISTORICAL SOCIETY BffiLIOGRAPHY OF METHODIST HISTORICAL LITERATURE, 2006 BIBLIOGRAPHIES I. FIELD, Clive Douglas: 'Bibliography of Methodist historical literature, 2005', Proceedings of the Wesley Historical Society, Vol. 55, Pt. 5 (Supplement), May 2006, pp. 209-35. 2. MADDEN, John Lionel: 'Cyhoeddiadau diweddar ar Fethodistiaeth Galfinaidd yng Nghymru, 2005/recent publications on Welsh Calvinistic Methodism, 2005', Cylchgrawn Hanes, Vol. 29/30, 2005/06, pp. 148-50. 3. RODDIE, Robin Parker: 'Bibliography of Irish Methodist historical literature, 2006', Bulletin of the Wesley Historical Society in Ireland, Vol. 12,2006-07, pp. 74-6. 4. TYSON, John Rodger: 'Charles Wesley bibliography', AsbU/y Journal, Vol. 61, No. 1, Spring 2006, pp. 64-6. See also Nos. 143, 166. GUIDES TO SOURCES AND ARCHIVES 5. CORNWALL RECORD OFFICE: Methodist registers held at Cornwall Record Office: Baptisms, burials & marriages, 1837-1900 [surname indexes], compiled by Sheila Townsend and Stephen Townsend, St. Austell: Shelkay, 2004, 20 vol., CD-ROM. 6. KISBY, Fiona: 'In hortis reginae: An introduction to the archives of Queenswood School', Recordkeeping, Winter 2006, pp. 20-3. 7. MADDEN, John Lionel: 'John Wesley's Methodists: Their confusing history and complicated records', Cronicl Powys, No. 67, April 2006, pp. 32-40. 8. MADDEN, John Lionel: Yr Eurgrawn (Wesleyaidd), 1809-1983: mynegai i ysgrifau am weinidogion [index to writings about ministers in the Welsh Wesleyan magazine], Aberystwyth: Yr Eglwys Fethodistaidd, Cymdeithas Hanes Talaith Cymru, 2006, 46pp. -

Post-Conquest Medieval

Medieval 12 Post-Conquest Medieval Edited by Stephen Rippon and Bob Croft from contributions by Oliver Creighton, Bob Croft and Stephen Rippon 12.1 Introduction economic transformations reflected, for example, in Note The preparation of this assessment has been the emergence, virtual desertion and then revival of an hampered by a lack of information and input from some urban hierarchy, the post-Conquest Medieval period parts of the region. This will be apparent from the differing was one of relative social, political and economic levels of detail afforded to some areas and topics, and the continuity. Most of the key character defining features almost complete absence of Dorset and Wiltshire from the of the region – the foundations of its urban hier- discussion. archy, its settlement patterns and field systems, its The period covered by this review runs from the industries and its communication systems – actually Norman Conquest in 1066 through to the Dissolu- have their origins in the pre-Conquest period, and tion of the monasteries in the 16th century, and unlike the 11th to 13th centuries simply saw a continua- the pre-Conquest period is rich in both archaeology tion of these developments rather than anything radi- (including a continuous ceramic sequence across the cally new: new towns were created and monas- region) and documentary sources. Like every region teries founded, settlement and field systems spread of England, the South West is rich in Medieval archae- out into the more marginal environments, industrial ology preserved within the fabric of today’s historic production expanded and communication systems landscape, as extensive relict landscapes in areas of were improved, but all of these developments were the countryside that are no longer used as inten- built on pre-Conquest foundations (with the excep- sively as they were in the past, and buried beneath tion of urbanisation in the far south-west). -

Dudley Baines Has Posed a Key Question for Migration Historians

“WE DON’T TRAVEL MUCH … ONLY TO SOUTH AFRICA”: RECONSTRUCTING NINETEENTH CENTURY CORNISH MIGRATION PATTERNS Bernard Deacon (in Philip Payton (ed.), Cornish Studies Fifteen, University of Exeter Press, 2007, pp.90-106) INTRODUCTION Dudley Baines poses a key question about nineteenth-century migration: ‘why did some places produce relatively more migrants than others which were outwardly similar?’1 Yet pursuing an answer to this question is problematic in two ways. First, there is no agreed consensus on the scale to be adopted. In Britain most demographic data available to the historian of nineteenth century migration is organised at regional, county or at registration district (RD) level. The average size of the latter units were around 20,000 people. Although this enables investigation at a sub-county level, meeting Baines’ point that neither regional nor county scale is sufficiently sensitive to answer the relative migration question, it does not allow for easy testing of his further suggestion that the appropriate migration unit might be at the much smaller village or local community level. But the fluid process of immigration may need to be approached more flexibly. Charles Tilly has argued that the ‘effective units of migration were (and are) neither individuals nor households but sets of people linked by acquaintance, kinship and work experience’.2 Transferring attention in this way from spatial units to neighbourhood, family or occupational networks tends to emphasise one of the broad approaches put forward by migration historians -

Election of Town and Parish Councillors Notice Is Hereby Given That 1

Notice of Election Election of Town and Parish Councillors Notice is hereby given that 1. Elections are to be held of Town and Parish Councillors for each of the under-mentioned Town and Parish Councils. If the elections are contested the poll will take place on Thursday 2 May, 2013. 2. I have appointed Geoff Waxman, Sharon Holland and John Simmons whose offices are Room 33, Cornwall Council, Luxstowe House, Liskeard, PL14 3DZ to be my Deputies and are specifically responsible for the following Town and Parishes: Town / Parish Seats Town / Parish Seats Town / Parish Seats Altarnun 6 Maker with Rame 11 St Eval 7 Antony 6 Marhamchurch 10 St Ewe 10 Blisland 10 Mawgan-in-Pydar (St. Mawgan Ward) 6 St Gennys 10 Bodmin (St Leonard Ward) 5 Mawgan-in-Pydar (Trenance Ward) 6 St Germans (Bethany Ward) 2 Bodmin (St Mary's Ward) 6 Menheniot 11 St Germans (Polbathic Ward) 2 Bodmin (St Petroc Ward) 5 Mevagissey 14 St Germans (St Germans Ward) 4 Botus Fleming 8 Michaelstow 5 St Germans (Tideford Ward) 3 Boyton 8 Millbrook 13 St Goran 10 Bude-Stratton (Bude Ward) 9 Morval 10 St Issey 10 Bude-Stratton (Flexbury and Poughill Ward) 6 Morwenstow 10 St Ive (Pensilva Ward) 10 Bude-Stratton (Stratton Ward) 3 Newquay (Newquay Central Ward) 3 St Ive (St Ive Ward) 3 Callington (Callington Ward) 10 Newquay (Newquay Pentire Ward) 4 St John 6 Callington (Kelly Bray Ward) 2 Newquay (Newquay Treloggan Ward) 4 St Juliot 5 Calstock (Calstock Ward) 3 Newquay (Newquay Tretherras Ward) 3 St Kew (Pendoggett Ward) 1 Calstock (Chilsworthy Ward) 2 Newquay (Newquay Treviglas -

23 New Cottages, Kilkhampton, Cornwall, EX23 9QH

OPEN 7 DAYS A WEEK 23 New Cottages Kilkhampton, Cornwall, EX23 9QH . Overview An opportunity to acquire a 2 bedroom character cottage in need of some modernisation in the heart of this self contained village. Generous size garden and garage to rear with vehicular access. No ongoing chain. Freehold £162,000 . .5 34 Queen Street, Bude, Cornwall EX23 8BB Bond Oxborough Phillips T 01288 355066 F 01288 355982 INDEPENDENT ESTATE AGENTS The key to moving home E [email protected] 23 New Cottages, Kilkhampton, Cornwall, EX23 9QH LOCATION 23 New Cottages enjoys a pleasant position within this self contained rural village, situated close to the centre with all its local amenities including Village Store, Newsagents, Places of Worship, Bakery, Butcher, Electrical Wholesaler, Primary School and popular local inns etc. The coastal town of Bude is some 5 miles supporting an extensive range of shopping, schooling and recreational facilities as well as lying amidst the rugged North Cornish coastline famed for its many nearby areas of outstanding natural beauty and popular bathing beaches offering a whole host of watersports and leisure activities together with breathtaking cliff top coastal walks. The bustling market town of Holsworthy lies some 10 miles inland whilst the port and market town of Bideford lying some 24 miles in a north easterly direction provides a convenient access to the A39 North Devon Link Road which connects in turn to Barnstaple, Tiverton and the M5 motorway. DIRECTIONS TO FIND From Bude town centre proceed out of town towards Stratton. upon reaching the A39 turn left signposted Bideford and proceed for approximately 4 miles to Kilkhampton. -

Cornwall Housing Tenants Newsletter DECEMBER 2013

Tenants’ voice Cornwall Housing Tenants Newsletter DECEMBER 2013 At the end of September father and son John (left) and Matthew (right) Harris from Launceston both graduated from the Open University, being presented with their degrees by Sir Terry Pratchett. Many congratulations to them both. John’s story is below. IT’S NEVER TOO LATE family or just never had the If, like John, Matthew, your TO LEARN... opportunity. editor and many thousands of other people who have taken On Saturday 28th September 2013 Now, thanks to that great advantage of the Open a soon to be 54 year old mature institution the Open University University’s courses over the student gained a degree. It had men and women, people from any years, you are inspired to try it taken six years of hard work, but and all backgrounds, regardless of for yourself, you can check out after the hundreds of late nights, the usual social and economic the possibilities at early mornings and any time in barriers which still blight our www.open.ac.uk between when an odd half hour society, have made the decision to studying period could be squeezed plunge into the world of learning, in I found myself up on a stage in open our minds and realize our Also in this edition: Portsmouth's Guildhall shaking potential. It’s not easy - in fact it's hands with the vice chancellor of damn hard work, but whether it's ! A spring garden in the university and collecting my to get a job, promotion or just for St Kew Highway degree.