Dudley Baines Has Posed a Key Question for Migration Historians

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Parish Boundaries

Parishes affected by registered Common Land: May 2014 94 No. Name No. Name No. Name No. Name No. Name 1 Advent 65 Lansall os 129 St. Allen 169 St. Martin-in-Meneage 201 Trewen 54 2 A ltarnun 66 Lanteglos 130 St. Anthony-in-Meneage 170 St. Mellion 202 Truro 3 Antony 67 Launce lls 131 St. Austell 171 St. Merryn 203 Tywardreath and Par 4 Blisland 68 Launceston 132 St. Austell Bay 172 St. Mewan 204 Veryan 11 67 5 Boconnoc 69 Lawhitton Rural 133 St. Blaise 173 St. M ichael Caerhays 205 Wadebridge 6 Bodmi n 70 Lesnewth 134 St. Breock 174 St. Michael Penkevil 206 Warbstow 7 Botusfleming 71 Lewannick 135 St. Breward 175 St. Michael's Mount 207 Warleggan 84 8 Boyton 72 Lezant 136 St. Buryan 176 St. Minver Highlands 208 Week St. Mary 9 Breage 73 Linkinhorne 137 St. C leer 177 St. Minver Lowlands 209 Wendron 115 10 Broadoak 74 Liskeard 138 St. Clement 178 St. Neot 210 Werrington 211 208 100 11 Bude-Stratton 75 Looe 139 St. Clether 179 St. Newlyn East 211 Whitstone 151 12 Budock 76 Lostwithiel 140 St. Columb Major 180 St. Pinnock 212 Withiel 51 13 Callington 77 Ludgvan 141 St. Day 181 St. Sampson 213 Zennor 14 Ca lstock 78 Luxul yan 142 St. Dennis 182 St. Stephen-in-Brannel 160 101 8 206 99 15 Camborne 79 Mabe 143 St. Dominic 183 St. Stephens By Launceston Rural 70 196 16 Camel ford 80 Madron 144 St. Endellion 184 St. Teath 199 210 197 198 17 Card inham 81 Maker-wi th-Rame 145 St. -

Wind Turbines East Cornwall

Eastern operational turbines Planning ref. no. Description Capacity (KW) Scale Postcode PA12/02907 St Breock Wind Farm, Wadebridge (5 X 2.5MW) 12500 Large PL27 6EX E1/2008/00638 Dell Farm, Delabole (4 X 2.25MW) 9000 Large PL33 9BZ E1/90/2595 Cold Northcott Farm, St Clether (23 x 280kw) 6600 Large PL15 8PR E1/98/1286 Bears Down (9 x 600 kw) (see also Central) 5400 Large PL27 7TA E1/2004/02831 Crimp, Morwenstow (3 x 1.3 MW) 3900 Large EX23 9PB E2/08/00329/FUL Redland Higher Down, Pensilva, Liskeard 1300 Large PL14 5RG E1/2008/01702 Land NNE of Otterham Down Farm, Marshgate, Camelford 800 Large PL32 9SW PA12/05289 Ivleaf Farm, Ivyleaf Hill, Bude 660 Large EX23 9LD PA13/08865 Land east of Dilland Farm, Whitstone 500 Industrial EX22 6TD PA12/11125 Bennacott Farm, Boyton, Launceston 500 Industrial PL15 8NR PA12/02928 Menwenicke Barton, Launceston 500 Industrial PL15 8PF PA12/01671 Storm, Pennygillam Industrial Estate, Launceston 500 Industrial PL15 7ED PA12/12067 Land east of Hurdon Road, Launceston 500 Industrial PL15 9DA PA13/03342 Trethorne Leisure Park, Kennards House 500 Industrial PL15 8QE PA12/09666 Land south of Papillion, South Petherwin 500 Industrial PL15 7EZ PA12/00649 Trevozah Cross, South Petherwin 500 Industrial PL15 9LT PA13/03604 Land north of Treguddick Farm, South Petherwin 500 Industrial PL15 7JN PA13/07962 Land northwest of Bottonett Farm, Trebullett, Launceston 500 Industrial PL15 9QF PA12/09171 Blackaton, Lewannick, Launceston 500 Industrial PL15 7QS PA12/04542 Oak House, Trethawle, Horningtops, Liskeard 500 Industrial -

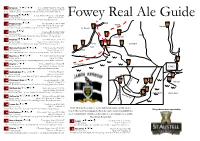

Fowey, Looe & Polperro Real Ale Pub Guide

1 Britannia St Austell Rd, Tregrehan, PL24 2SL (01726) 812889 Open 11-11 Sat 11-12 Sun 12-10.30 Large family free house, serving Fuller’s London Pride, Bass and Cornish ale. 2 Four Lords St Austell Rd, St Blazey Gate, PL24 2EE (01726) 814200 Open 12-12 Sat 11-12 Fowey Real Ale Guide Friendly local St Austell pub, 2 St Austell ales. Pub is allegedly haunted. B390 3 Packhorse Inn Fore St, St Blazey, PL24 2NH B3269 10 (01726) 813970 Open 10-4 5-12 Sat 10-12 Sun 12-11 3 Golant A historical coaching inn, now welcoming free house. Tintagel & Bays ale. St. Blazey 4 Par Inn 2 Harbour Rd, Par, PL24 2BD 7 (01726) 815695 Open 11-11 Sat 11-12 Sun 12-11 5 B3269 Unpretentious St Austell pub. Regular live music and disco. 3 St Austell ales Tywardreath 5 Royal Inn 66 Eastcliff Rd, Par, PL24 2AJ (01726) 815601 Open 11-11 Fri-Sat 11-12 Sun 12-11 A modern pub near Par railway station. Regular entertainment. Sharp’s ales. 2 St. Blazey 4 6 8 Lanteglos Gate 6 Welcome Home Inn 39 Par Green, Par, PL24 2AF 1 Par (01726) 816894 Open 11-12 Sun 11-11 B390 A St Austell owned village local. An open fire & large garden. 3 St Austell ales. A3082 7 New Inn Fore St, Tywardreath, PL24 2QP Par Moor Rd (01726) 813901 Open 12-11 Daily Welcoming village pub, up to 5 ales including Bass by gravity. Bistro style food. 11 9 8 Ship Inn Polmear Hill, Polmear, PL24 2AR Carlyon Bay (01726) 812540 Open Daily 11.30-12 Sun 12-11.30 FOWEYFowey A free house regular ales include Doom Bar and London Pride. -

Fortuna Villa Phillack, Hayle, Cornwall

Fortuna Villa Phillack, Hayle, Cornwall An imposing Victorian south-facing family residence with attractive bay windows and beautiful views over the surrounding countryside and with easy access to the beaches at St. Ives Bay. Guide Price £750,000 Features The Property • Reception Hall Built in 1898, this late Victorian gentleman’s • Drawing Room residence offers well-proportioned family • Sun Room accommodation. The current owners have carried out a schedule of improvements over • Kitchen with Rayburn their ownership, including replacing the majority • Utility Room of windows with hardwood double glazed • 2 Bedrooms with En-Suite Shower windows. The ground floor enjoys generous Rooms accommodation. The dining and drawing room • 4 Further Bedrooms at the front of the property both enjoying • Bathroom splendid views over the surrounding countryside and down towards Hayle. Off the drawing room • Separate Cloakroom is a sunroom that has enjoyed many different • Garages guises over the years. The first floor houses • Workshop three double bedrooms, a single bedroom, • Gardens bathroom and W.C . Up on the second floor there are two further bedrooms both with en-suite shower rooms. Distances The property leads onto the cliff path with easy access to the beach. Ideal for families, dog • Hayle 1.5 miles walkers or runners. • St . Ives 8.8 miles • Penzance 11.2 miles • Truro 18.6 miles • Newquay Airport 33.2 miles (D istances approximate) The Location Fortuna Villa occupies a delightful position facing almost due south and within easy reach of a wide range of local amenities to be found at nearby Copperhouse and Hayle. It Is on Phillack Towans, an expanse of sand dunes which form a backdrop to the miles of golden sand that make up Hayle Beach. -

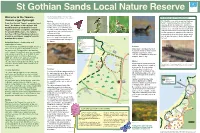

St Gothian Sands Local Nature Reserve

St Gothian Sands Local Nature Reserve As the seasons change, look out for the Welcome to the Towans - following wildlife in this part of the towans: St Gothian Sands’ Industrial past Towans a’gas Dynnergh Spring The Red River enters the sea at the Gwithian From the Cornish ‘Tewyn’, meaning ‘sand From early March, flocks of sand beach. It gets its name from mineral waste dune’, the towans between Hayle and martins, with swallows and house associated with tin mining in the Camborne/ Gwithian make up Cornwall’s second martins can be seen skimming over Redruth area. In the late 19th century, deposits of tin ore were extracted from the beach sand largest sand dune ecosystem, extending the water in the main lagoon. These Cinnabar moth migrants have just returned from over- and processed on site. Horses and carts were for around 400 hectares. The famous Photo Credit: David Chapman wintering in Africa. used to transport the sand as well as buckets beaches of St Ives Bay lying below you Stonechat Skylark suspended on wires attached to pylons which provide a continuous supply of sand to Wheatears have also come back - were bedded in concrete blocks and can still these are easily viewed on the open maintain these dunes. St Gothian Sands Key be seen. dune grasslands around the edge of Path NORTH the lagoon. Track St Gothian Sands – Ownership and Minor road National Trust Fencing P car park Moorhen explanation of name Power lines Electricity station Concrete blocks (tin streaming) (tin streaming) Formerly known as Gwithian Sandpit, this area Sand areas Autumn was a focus for gravel and sand extraction Sand areas with stone Many waders and waterfowl visit Marram grass for many years- for agriculture and building – Chimney St Gothian Sands on their autumn Scale until Cornwall Council took over the ownership 100m migration south for the winter. -

St Blazey Fowey and Lostwithiel Cormac Community Programme

Cormac Community Programme St Blazey, Fowey and Lostwithiel Community Network Area ........ Please direct any enquiries to [email protected] ...... Project Name Anticipated Anticipated Anticipated Worktype Location Electoral Division TM Type - Primary Duration Start Finish MID MID-St Blazey Fowey & Lostwithiel Contracting St Austell Bay Resilient Regeneration (ERDF) Construction - Various Locations 443 d Jul 2020 Apr 2022 Major Contracts (MCCL) St Blazey Area Fowey Tywardreath & Par Various (See Notes) Doubletrees School, St Austell Carpark Tank 211 d Apr 2021 Feb 2022 Environmental Capital Safety Works (ENSP) St Austell St Blazey 2WTL (2 Way Signals) Luxulyan Valley_St Austell_Benches, Signs 19 d Jun 2021 Aug 2021 Environmental Capital Safety Works (ENSP) St Austell Lostwithiel & Lanreath TBC Luxulyan Valley_St Austell_Path Works 130 d Jul 2021 Feb 2022 Environmental Capital Safety Works (ENSP) St Austell Lostwithiel & Lanreath Not Required Luxulyan Valley_St Austell_Riverbank Repairs (Cam Bridges Lux Phase 1) 14 d Aug 2021 Sep 2021 Environmental Capital Safety Works (ENSP) St Austell Lostwithiel & Lanreath Not Required Luxulyan Valley_St Austell_Drainage Feature (Leat Repairs Trail) 15 d Sep 2021 Sep 2021 Environmental Capital Safety Works (ENSP) St Austell Lostwithiel & Lanreath TBC Bull Engine, Par -Skate Park Equipment Design & Installation 10 d Nov 2021 Nov 2021 Environmental Capital Safety Works (ENSP) Par Fowey Tywardreath & Par Not Required Luxulyan Valley, St Austell -Historic Structures 40 d Nov 2021 Jan 2022 Environmental -

1860 Cornwall Quarter Sessions and Assizes

1860 Cornwall Quarter Sessions and Assizes Table of Contents 1. Epiphany Sessions .......................................................................................................... 1 2. Lent Assizes .................................................................................................................. 19 3. Easter Sessions ............................................................................................................. 64 4. Midsummer Sessions ................................................................................................... 79 5. Summer Assizes ......................................................................................................... 102 6. Michaelmas Sessions.................................................................................................. 125 Royal Cornwall Gazette 6th January 1860 1. Epiphany Sessions These Sessions opened at 11 o’clock on Tuesday the 3rd instant, at the County Hall, Bodmin, before the following Magistrates: Chairmen: J. JOPE ROGERS, ESQ., (presiding); SIR COLMAN RASHLEIGH, Bart.; C.B. GRAVES SAWLE, Esq. Lord Vivian. Edwin Ley, Esq. Lord Valletort, M.P. T.S. Bolitho, Esq. The Hon. Captain Vivian. W. Horton Davey, Esq. T.J. Agar Robartes, Esq., M.P. Stephen Nowell Usticke, Esq. N. Kendall, Esq., M.P. F.M. Williams, Esq. R. Davey, Esq., M.P. George Williams, Esq. J. St. Aubyn, Esq., M.P. R. Gould Lakes, Esq. W.H. Pole Carew, Esq. C.A. Reynolds, Esq. F. Rodd, Esq. H. Thomson, Esq. Augustus Coryton, Esq. Neville Norway, Esq. Harry Reginald -

Cornwall Council Altarnun Parish Council

CORNWALL COUNCIL THURSDAY, 4 MAY 2017 The following is a statement as to the persons nominated for election as Councillor for the ALTARNUN PARISH COUNCIL STATEMENT AS TO PERSONS NOMINATED The following persons have been nominated: Decision of the Surname Other Names Home Address Description (if any) Returning Officer Baker-Pannell Lisa Olwen Sun Briar Treween Altarnun Launceston PL15 7RD Bloomfield Chris Ipc Altarnun Launceston Cornwall PL15 7SA Branch Debra Ann 3 Penpont View Fivelanes Launceston Cornwall PL15 7RY Dowler Craig Nicholas Rivendale Altarnun Launceston PL15 7SA Hoskin Tom The Bungalow Trewint Marsh Launceston Cornwall PL15 7TF Jasper Ronald Neil Kernyk Park Car Mechanic Tredaule Altarnun Launceston Cornwall PL15 7RW KATE KENNALLY Dated: Wednesday, 05 April, 2017 RETURNING OFFICER Printed and Published by the RETURNING OFFICER, CORNWALL COUNCIL, COUNCIL OFFICES, 39 PENWINNICK ROAD, ST AUSTELL, PL25 5DR CORNWALL COUNCIL THURSDAY, 4 MAY 2017 The following is a statement as to the persons nominated for election as Councillor for the ALTARNUN PARISH COUNCIL STATEMENT AS TO PERSONS NOMINATED The following persons have been nominated: Decision of the Surname Other Names Home Address Description (if any) Returning Officer Kendall Jason John Harrowbridge Hill Farm Commonmoor Liskeard PL14 6SD May Rosalyn 39 Penpont View Labour Party Five Lanes Altarnun Launceston Cornwall PL15 7RY McCallum Marion St Nonna's View St Nonna's Close Altarnun PL15 7RT Richards Catherine Mary Penpont House Altarnun Launceston Cornwall PL15 7SJ Smith Wes Laskeys Caravan Farmer Trewint Launceston Cornwall PL15 7TG The persons opposite whose names no entry is made in the last column have been and stand validly nominated. -

Eventsmay-Aug2015

‘FRIENDS OF THE TOWANS’ Events May -August 2015 Summary of recent activities Hello again, how time flies……yesterday was Helston Flora Day, as well as Election results day, so we now know that spring has definitely sprung and that ‘summer has a-come-o’. I’m sure you’ve all had enough of statistics over the last day or so (I know I have), so I’ll just very briefly linger on the facts and figures of our recent outings and then look ahead to future work and events. In a nutshell, since our outing on March 18th, when Dorothy and I hacked some lumps out of the sea buckthorn on St Ives Bay, each outing has more or less doubled in attendance figures. Ten of us enjoyed a walk in St Gothians and then around Gwithian Green on April 25th. It was a bit cool and cloudy, but we did see signs of spring in the form of a cuckoo, two broods of mallard ducklings, sand martins and a flock of whimbrel (a small migratory curlew), en-route from Africa to the Arctic Circle to breed. Cowslips were abundant on Gwithian Green. We also removed litter, including fairly significant amounts of dog waste from the sites. As we know, this is one of the issues that often spoils a visit to the Towans, so I am grateful for your willingness to help remove at least some of it. One of the other purposes in running these events is to improve people’s knowledge of various parts of the Towans, so it’s good that several of the group ‘discovered’ the gem that is Gwithian Green Nature Reserve on that day. -

Camborne, Pool & Redruth Place Based Issues

Camborne, Pool & Redruth Place Based Issues Paper - January 2012 Contents CORNWALL LDF: CORE STRATEGY PLACE-BASED ISSUES PAPER: CAMBORNE, POOL AND REDRUTH COMMUNITY 1 NETWORK AREA Summary 1 Purpose of paper 1 Camborne, Pool and Redruth Community Network Area 2 Key Facts 3 Introduction 5 Housing 6 Local Economy 8 Retail and Town Centres 10 Transport and Accessibility 12 Community facilities 14 People 16 Environment 18 Coast 20 Summary and Key Spatial Issues 22 Appendix A: Community Planning Area Visions / Key Objectives 22 Appendix B: Landscape Character information from the 2007 26 Cornwall Landscape Character Assessment Camborne, Pool & Redruth Place Based Issues Paper - January 2012 Contents Camborne, Pool & Redruth Place Based Issues Paper - January 2012 1 Cornwall LDF: Core Strategy Place-based Issues Paper: Camborne, Pool and Redruth Community Network Area Cornwall LDF: Core Strategy Place-based Issues Paper: Camborne, Pool and Redruth Community Network Area Summary Table .1 This paper summarises the key emerging issues for the Camborne and Redruth Community Network Area brought together to inform the Cornwall Core Strategy. The key issues: Issue 1 – Enable higher quality employment opportunities. Issue 2 – Manage the level and distribution of housing growth, taking into consideration the Camborne, Pool, Illogan, Redruth Area Action Plan research and evidence base. Issue 3 – Promote a positive relationship between the retail centres of Camborne, Pool and Redruth, strengthening comparison shopping. Issue 4 – Enhance sports and leisure facilities to serve population growth. Issue 5 – Reduce deprivation through allocation of land for services, open space and through high quality design. Issue 6 – Remediate contaminated land. Purpose of paper This is one of a series of papers whose main purpose is to identify the key issues for a specific area of Cornwall. -

Cornwall Local Plan: Community Network Area Sections

Planning for Cornwall Cornwall’s future Local Plan Strategic Policies 2010 - 2030 Community Network Area Sections www.cornwall.gov.uk Dalghow Contents 3 Community Networks 6 PP1 West Penwith 12 PP2 Hayle and St Ives 18 PP3 Helston and South Kerrier 22 PP4 Camborne, Pool and Redruth 28 PP5 Falmouth and Penryn 32 PP6 Truro and Roseland 36 PP7 St Agnes and Perranporth 38 PP8 Newquay and St Columb 41 PP9 St Austell & Mevagissey; China Clay; St Blazey, Fowey & Lostwithiel 51 PP10 Wadebridge and Padstow 54 PP11 Bodmin 57 PP12 Camelford 60 PP13 Bude 63 PP14 Launceston 66 PP15 Liskeard and Looe 69 PP16 Caradon 71 PP17 Cornwall Gateway Note: Penzance, Hayle, Helston, Camborne Pool Illogan Redruth, Falmouth Penryn, Newquay, St Austell, Bodmin, Bude, Launceston and Saltash will be subject to the Site Allocations Development Plan Document. This document should be read in conjunction with the Cornwall Local Plan: Strategic Policies 2010 - 2030 Community Network Area Sections 2010-2030 4 Planning for places unreasonably limiting future opportunity. 1.4 For the main towns, town frameworks were developed providing advice on objectives and opportunities for growth. The targets set out in this plan use these as a basis for policy where appropriate, but have been moderated to ensure the delivery of the wider strategy. These frameworks will form evidence supporting Cornwall Allocations Development Plan Document which will, where required, identify major sites and also Neighbourhood Development Plans where these are produced. Town frameworks have been prepared for; Bodmin; Bude; Camborne-Pool-Redruth; Falmouth Local objectives, implementation & Penryn; Hayle; Launceston; Newquay; Penzance & Newlyn; St Austell, St Blazey and Clay Country and monitoring (regeneration plan) and St Ives & Carbis Bay 1.1 The Local Plan (the Plan) sets out our main 1.5 The exception to the proposed policy framework planning approach and policies for Cornwall. -

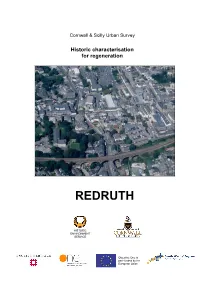

Redruth Main Report

Cornwall & Scilly Urban Survey Historic characterisation for regeneration REDRUTH HISTORIC ENVIRONMENT SERVICE Objective One is part-funded by the European Union Cornwall and Scilly Urban Survey Historic characterisation for regeneration REDRUTH Kate Newe ll June 2004 HES REPORT NO. 2004R037 HISTORIC ENVIRONMENT SERVICE Environment and Heritage Service, Planning Transportation and Estates, Cornwall County Council Kennall Building, Old County Hall, Station Road, Truro, Cornwall, TR1 3AY tel (01872) 323603 fax (01872) 323811 E-mail [email protected] Acknowledgements This report was produced as part of the Cornwall & Scilly Urban Survey project (CSUS), funded by English Heritage, the Objective One Partnership for Cornwall and the Isles of Scilly (European Regional Development Fund) and the South West Regional Development Agency (South West RDA). Peter Beacham (Head of Designation), Graham Fairclough (Head of Characterisation), Roger M Thomas (Head of Urban Archaeology), Jill Guthrie (Designation Team Leader, South West) and Ian Morrison (Ancient Monuments Inspector for Devon, Cornwall and Isles of Scilly) liaised with the project team for English Heritage and provided valuable advice, guidance and support. Nick Cahill (The Cahill Partnership) acted as Conservation Advisor to the project, providing support with the characterisation methodology and advice on the interpretation of individual settlements. Georgina McLaren (Cornwall Enterprise) performed an equally significant advisory role on all aspects of economic regeneration. Additional help has been given by Andrew Richards (Conservation Officer, Kerrier District Council). Mike Horrocks (then Community Regeneration Officer Redruth Area, Tin Country Partnership, IAP) and John Dobson (then Camborne – Pool – Redruth Principal Regeneration Manager Objective 1, South West RDA) provided valuable information regarding regeneration proposals and initiatives.