A Quest for Plausible Libertarianism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Political Ideas and Movements That Created the Modern World

harri+b.cov 27/5/03 4:15 pm Page 1 UNDERSTANDINGPOLITICS Understanding RITTEN with the A2 component of the GCE WGovernment and Politics A level in mind, this book is a comprehensive introduction to the political ideas and movements that created the modern world. Underpinned by the work of major thinkers such as Hobbes, Locke, Marx, Mill, Weber and others, the first half of the book looks at core political concepts including the British and European political issues state and sovereignty, the nation, democracy, representation and legitimacy, freedom, equality and rights, obligation and citizenship. The role of ideology in modern politics and society is also discussed. The second half of the book addresses established ideologies such as Conservatism, Liberalism, Socialism, Marxism and Nationalism, before moving on to more recent movements such as Environmentalism and Ecologism, Fascism, and Feminism. The subject is covered in a clear, accessible style, including Understanding a number of student-friendly features, such as chapter summaries, key points to consider, definitions and tips for further sources of information. There is a definite need for a text of this kind. It will be invaluable for students of Government and Politics on introductory courses, whether they be A level candidates or undergraduates. political ideas KEVIN HARRISON IS A LECTURER IN POLITICS AND HISTORY AT MANCHESTER COLLEGE OF ARTS AND TECHNOLOGY. HE IS ALSO AN ASSOCIATE McNAUGHTON LECTURER IN SOCIAL SCIENCES WITH THE OPEN UNIVERSITY. HE HAS WRITTEN ARTICLES ON POLITICS AND HISTORY AND IS JOINT AUTHOR, WITH TONY BOYD, OF THE BRITISH CONSTITUTION: EVOLUTION OR REVOLUTION? and TONY BOYD WAS FORMERLY HEAD OF GENERAL STUDIES AT XAVERIAN VI FORM COLLEGE, MANCHESTER, WHERE HE TAUGHT POLITICS AND HISTORY. -

Unit 5 Equality

UNIT 5 EQUALITY Structure 5.1 Introduction 5.2 Equality vs. Inequality 5.2.1 Struggle for Equality 5.3 What is Equality? 5.4 Dimensions of Equality 5.4.1 Legal Equality 5.4.2 Political Equality 5.4.3 Economic Equality 5.4.4 Social Equality 5.5 Relation of Equality with Liberty and Justice 5.5.1 Equality and Liberty As Opposed To Each Other 5.5.2 Equality and Liberty Are Complementary To Each Other 5.5.3 Equality and Justice 5.6 Towards Equality 5.7 Plea for Inequality in the Contemporary World 5.8 Marxist Concept of Equality 5.9 Summary 5.10 Exercises 5.1 INTRODUCTION Of all the basic concepts of social, economic, moral and political philosophy, none is more confusing and baffling than the concept of equality because it figures in all other concepts like justice, liberty, rights, property, etc. During the last two thousand years, many dimensions of equality have been elaborated by Greeks, Stoics, Christian fathers who separately and collectively stressed on its one or the other aspect. Under the impact of liberalism and Marxism, equality acquired an altogether different connotation. Contemporary social movements like feminism, environmentalism are trying to give a new meaning to this concept. Basically, equality is a value and a principle essentially modern and progressive. Though the debate about equality has been going on for centuries, the special feature of modern societies is that we no longer take inequality for granted or something natural. Equality is also used as a measure of what is modern and the whole process of modernisation in the form of political egalitarianism. -

Libertarianism, Culture, and Personal Predispositions

Undergraduate Journal of Psychology 22 Libertarianism, Culture, and Personal Predispositions Ida Hepsø, Scarlet Hernandez, Shir Offsey, & Katherine White Kennesaw State University Abstract The United States has exhibited two potentially connected trends – increasing individualism and increasing interest in libertarian ideology. Previous research on libertarian ideology found higher levels of individualism among libertarians, and cross-cultural research has tied greater individualism to making dispositional attributions and lower altruistic tendencies. Given this, we expected to observe positive correlations between the following variables in the present research: individualism and endorsement of libertarianism, individualism and dispositional attributions, and endorsement of libertarianism and dispositional attributions. We also expected to observe negative correlations between libertarianism and altruism, dispositional attributions and altruism, and individualism and altruism. Survey results from 252 participants confirmed a positive correlation between individualism and libertarianism, a marginally significant positive correlation between libertarianism and dispositional attributions, and a negative correlation between individualism and altruism. These results confirm the connection between libertarianism and individualism observed in previous research and present several intriguing questions for future research on libertarian ideology. Key Words: Libertarianism, individualism, altruism, attributions individualistic, made apparent -

Up from Individualism (The Brennan Center Symposium On

University of Michigan Law School University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository Articles Faculty Scholarship 1998 Up from Individualism (The rB ennan Center Symposium on Constitutional Law)." Donald J. Herzog University of Michigan Law School, [email protected] Available at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/articles/141 Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/articles Part of the Jurisprudence Commons, Law and Society Commons, and the Public Law and Legal Theory Commons Recommended Citation Herzog, Donald J. "Up from Individualism (The rB ennan Center Symposium on Constitutional Law)." Cal. L. Rev. 86, no. 3 (1998): 459-67. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Articles by an authorized administrator of University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Up from Individualism Don Herzogt I was sitting, ruefully contemplating the dilemmas of being a com- mentator, wondering whether I had the effrontery to rise and offer a dreadful confession: the first time I encountered the counter- majoritarian difficulty, I didn't bite. I didn't say, "Wow, that's a giant problem." I didn't immediately start casting about for ingenious ways to solve or dissolve it. I just shrugged. Now I don't think that's because my commitments to either democracy or constitutionalism are somehow faulty or suspect. Nor do I think it's that they obviously cohere. It's rather that the framing, "look, these nine unelected characters can strike down a statute passed in procedurally valid ways by a democratically elected legislature," struck me as unhelpful. -

Me, Myself & Mine: the Scope of Ownership

ME, MYSELF & MINE The Scope of Ownership _________________________________ PETER MARTIN JAWORSKI _________________________________ May, 2012 Committee: Fred Miller (Chair) David Shoemaker, Steven Wall, Daniel Jacobson, Neil Englehart ii ABSTRACT This dissertation is an attempt to defend the following thesis: The scope of legitimate ownership claims is much more narrow than what Lockean liberals have traditionally thought. Firstly, it is more narrow with respect to the particular claims that are justified by Locke’s labour- mixing argument. It is more difficult to come to own things in the first place. Secondly, it is more narrow with respect to the kinds of things that are open to the ownership relation. Some things, like persons and, maybe, cultural artifacts, are not open to the ownership relation but are, rather, fit objects for the guardianship, in the case of the former, and stewardship, in the case of the latter, relationship. To own, rather than merely have a property in, some object requires the liberty to smash, sell, or let spoil the object owned. Finally, the scope of ownership claims appear to be restricted over time. We can lose our claims in virtue of a change in us, a change that makes it the case that we are no longer responsible for some past action, like the morally interesting action required for justifying ownership claims. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS: Much of this work has benefited from too many people to list. However, a few warrant special mention. My committee, of course, deserves recognition. I’m grateful to Fred Miller for his many, many hours of pouring over my various manuscripts and rough drafts. -

Free to Choose Video Tape Collection

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt1n39r38j No online items Inventory to the Free to Choose video tape collection Finding aid prepared by Natasha Porfirenko Hoover Institution Library and Archives © 2008 434 Galvez Mall Stanford University Stanford, CA 94305-6003 [email protected] URL: http://www.hoover.org/library-and-archives Inventory to the Free to Choose 80201 1 video tape collection Title: Free to Choose video tape collection Date (inclusive): 1977-1987 Collection Number: 80201 Contributing Institution: Hoover Institution Library and Archives Language of Material: English Physical Description: 10 manuscript boxes, 10 motion picture film reels, 42 videoreels(26.6 Linear Feet) Abstract: Motion picture film, video tapes, and film strips of the television series Free to Choose, featuring Milton Friedman and relating to laissez-faire economics, produced in 1980 by Penn Communications and television station WQLN in Erie, Pennsylvania. Includes commercial and master film copies, unedited film, and correspondence, memoranda, and legal agreements dated from 1977 to 1987 relating to production of the series. Digitized copies of many of the sound and video recordings in this collection, as well as some of Friedman's writings, are available at http://miltonfriedman.hoover.org . Creator: Friedman, Milton, 1912-2006 Creator: Penn Communications Creator: WQLN (Television station : Erie, Pa.) Hoover Institution Library & Archives Access The collection is open for research; materials must be requested at least two business days in advance of intended use. Publication Rights For copyright status, please contact the Hoover Institution Library & Archives. Acquisition Information Acquired by the Hoover Institution Library & Archives in 1980, with increments received in 1988 and 1989. -

Markets Not Capitalism Explores the Gap Between Radically Freed Markets and the Capitalist-Controlled Markets That Prevail Today

individualist anarchism against bosses, inequality, corporate power, and structural poverty Edited by Gary Chartier & Charles W. Johnson Individualist anarchists believe in mutual exchange, not economic privilege. They believe in freed markets, not capitalism. They defend a distinctive response to the challenges of ending global capitalism and achieving social justice: eliminate the political privileges that prop up capitalists. Massive concentrations of wealth, rigid economic hierarchies, and unsustainable modes of production are not the results of the market form, but of markets deformed and rigged by a network of state-secured controls and privileges to the business class. Markets Not Capitalism explores the gap between radically freed markets and the capitalist-controlled markets that prevail today. It explains how liberating market exchange from state capitalist privilege can abolish structural poverty, help working people take control over the conditions of their labor, and redistribute wealth and social power. Featuring discussions of socialism, capitalism, markets, ownership, labor struggle, grassroots privatization, intellectual property, health care, racism, sexism, and environmental issues, this unique collection brings together classic essays by Cleyre, and such contemporary innovators as Kevin Carson and Roderick Long. It introduces an eye-opening approach to radical social thought, rooted equally in libertarian socialism and market anarchism. “We on the left need a good shake to get us thinking, and these arguments for market anarchism do the job in lively and thoughtful fashion.” – Alexander Cockburn, editor and publisher, Counterpunch “Anarchy is not chaos; nor is it violence. This rich and provocative gathering of essays by anarchists past and present imagines society unburdened by state, markets un-warped by capitalism. -

Some Unpleasant Monetarist Arithmetic Thomas Sargent, ,, ^ Neil Wallace (P

Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis Quarterly Review Some Unpleasant Monetarist Arithmetic Thomas Sargent, ,, ^ Neil Wallace (p. 1) District Conditions (p.18) Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis Quarterly Review vol. 5, no 3 This publication primarily presents economic research aimed at improving policymaking by the Federal Reserve System and other governmental authorities. Produced in the Research Department. Edited by Arthur J. Rolnick, Richard M. Todd, Kathleen S. Rolfe, and Alan Struthers, Jr. Graphic design and charts drawn by Phil Swenson, Graphic Services Department. Address requests for additional copies to the Research Department. Federal Reserve Bank, Minneapolis, Minnesota 55480. Articles may be reprinted if the source is credited and the Research Department is provided with copies of reprints. The views expressed herein are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis or the Federal Reserve System. Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis Quarterly Review/Fall 1981 Some Unpleasant Monetarist Arithmetic Thomas J. Sargent Neil Wallace Advisers Research Department Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis and Professors of Economics University of Minnesota In his presidential address to the American Economic in at least two ways. (For simplicity, we will refer to Association (AEA), Milton Friedman (1968) warned publicly held interest-bearing government debt as govern- not to expect too much from monetary policy. In ment bonds.) One way the public's demand for bonds particular, Friedman argued that monetary policy could constrains the government is by setting an upper limit on not permanently influence the levels of real output, the real stock of government bonds relative to the size of unemployment, or real rates of return on securities. -

Chapter 18 County Budgets and Fiscal Control

CHAPTER 18 COUNTY BUDGETS AND FISCAL CONTROL Last Revision September, 2010 18.01 INTRODUCTION Balancing the Budget Ohio counties and other local political subdivisions are required by state law to adopt a budget resolution annually. Along with other local governmental entities, Ohio’s counties should adopt proper financial accounting, budgeting, and taxing standards as part of the requirement to maintain their fiscal integrity. 1 The basic outline of the county budget process is set by state law. Each board of county commissioners is required to pass an annual appropriation measure based on a “tax budget” that certifies that tax revenues and other receipts and resources will be sufficient to meet planned expenditures. It should be noted that ORC Section 5705.281 allows the county budget commission to waive the tax budget, and a number of counties have implemented this authority. For those counties that have waived the tax budget, the county budget commission may require the commissioners to provide other information during the budget process. See Section 18.10 for additional information. Counties maintain a variety of funds that support their programs and services. Budgeting by fund is a distinguishing feature of the public sector. State law recognizes 1 The roles and responsibilities of county offices are discussed in Section 18.02 of this Chapter, as well as in Chapter 1, and in the respective chapters of this Handbook , which are referred to in Chapter 1. 1 that balancing a county’s operating budget for each fund is at the heart of sound fiscal management. The following passage from the Ohio Revised Code (ORC) contains this fundamental requirement of balancing each fund within a county’s budget: The total appropriations from each fund shall not exceed the total of the estimated revenue available for expenditure therefrom, as certified by the budget commission, or in case of appeal, by the board of tax appeals. -

Forms of Government

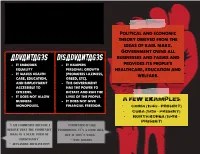

communism An economic ideology Political and economic theory derived from the ideas of karl marx. Government owns all Advantages DISAdvantages businesses and farms and - It embodies - It hampers provides its people's equality personal growth healthcare, education and - It makes health (promotes laziness, welfare. care, education, greed, etc). and employment - The government accessible to has the power to citizens. dictate and run the - It does not allow lives of the people. business - It does not give A Few Examples: monopolies. financial freedom. - China (1949 – Present) - Cuba (1959 – Present) - North Korea (1948 – Present) “I am communist because I “Communism is like believe that the comMunist prohibition. It’s a good idea, ideal is a state form of but it won’t work.” christianity” - will Rogers - Alexander Zhuravlyovv Socialism Government owns many of An Economic Ideology the larger industries and provide education, health and welfare services while Advantages DISAdvantages allowing citizens some - There is a balance - Bureaucracy hampers economic choices between wealth and the delivery of earnings services. - There is equal access - People are to health care and unmotivated to A Few Examples: education develop Vietnam - It breaks down social entrepreneurial skills. Laos barriers - The government has Denmark too much control Finland “The meaning of peace is “Socialism is workable only the absence of opposition to in heaven where it isn’t need socialism” and in where they’ve got it.” - Karl Marx - Cecil Palmer Capitalism Free-market -

Concepts of Inequality Development Issues No

Development Strategy and Policy Analysis Unit w Development Policy and Analysis Division Department of Economic and Social Affairs Concepts of Inequality Development Issues No. 1 21 October 2015 Inequality—the state of not being equal, especially in status, rights, and opportunities1—is a concept very much at the heart Summary of social justice theories. However, it is prone to confusion in public debate as it tends to mean different things to different The understanding of inequality has evolved from the people. Some distinctions are common though. Many authors traditional outcome-oriented view, whereby income is distinguish “economic inequality”, mostly meaning “income used as a proxy for well-being. The opportunity-oriented inequality”, “monetary inequality” or, more broadly, inequality perspective acknowledges that circumstances of birth are in “living conditions”. Others further distinguish a rights-based, essential to life outcomes and that equality of opportunity legalistic approach to inequality—inequality of rights and asso- requires a fair starting point for all. ciated obligations (e.g. when people are not equal before the law, or when people have unequal political power). Concerning economic inequality, much of the discussion has on poverty reduction. Pro-poor growth approaches made their boiled down to two views. One is chiefly concerned with the debut and growth and equity (through income redistribution) inequality of outcomes in the material dimensions of well-being were seen as separate policy instruments, each capable of address- and that may be the result of circumstances beyond one’s control ing poverty. The central concern was in raising the incomes of (ethnicity, family background, gender, and so on) as well as talent poor households. -

Justifying Group Intellectual Property: Applying Western Normative Principles to Justify Intangible Cultural Property

JUSTIFYING GROUP INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY: APPLYING WESTERN NORMATIVE PRINCIPLES TO JUSTIFY INTANGIBLE CULTURAL PROPERTY HARSHAVARDHAN GANESAN* I. INTRODUCTION What does Yoga,1 the German band Enigma,2 fan fiction,3 anti-fungal properties of Neem,4 Wikipedia,5 the Chain Art Project,6 and aboriginal paintings have in common? They all belong to a legal lacunae, a lacuna relating to group-rights (or collective rights) in Intellectual Property Law. Intellectual Property (‘IP’) has almost consistently, since its inception, romanticized the idea of a sole creator, or individual genius.7 This has deprived vast numbers of small, creative groups and indigenous people of IP protection, which has had varied effects on them, ranging from moral disparagement,8 to economic deprivation,9 and even cultural misappropriation.10 These events have not been ignored either at the domestic or international level however, with a steady consensus building up in favor of Cultural Property (‘CP’),11 particularly following the * Harshavardhan Ganesan is an advocate currently practicing in the Madras High Court with Senior Counsel, Mr. Satish Parasaran. 1 Stuart Schüssel, Copyright Protection Challenges and Alaska Natives' Cultural Property, 29 ALA. L. REV. 313, 315 (2012). 2 Timothy D. Taylor, A Riddle Wrapped in a Mystery: Transnational Music Sampling and Enigma's “Return to Innocence,” in MUSIC AND TECHNOCULTURE, 64, 68 (René T. A. Lysloff & Leslie C. Gay, Jr. eds., 2003). 3 Margaret Leidy, Protecting Creation: The Twilight Series, Creation Stories, and the Conversion of Intangible Cultural Property, 41 Sw. U. L. REV. 509 (2012). 4 Srividhya Ragavan, Protection of Traditional Knowledge, 2 MINN. INTELL. PROP.