University of Huddersfield Repository

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Peter Bowes Los Angeles Correspondent, BBC News

Peter Bowes Los Angeles Correspondent, BBC News Media Masters – August 11, 2016 Listen to the podcast online, visit www.mediafocus.org.uk Welcome to Media Masters, a series of one to one interviews with people at the top of the media game. Today I’m, joined by BBC correspondent Peter Bowes. Peter started out in scientific research before moving into broadcasting though local radio. He joined the BBC in 1988, working for Radio 4 on PM, The World at One and the Today programme, before moving to Radio 1 where he worked on the breakfast show and presented Newsbeat. He moved to the US in 1996. Based in Los Angeles, he has since covered a huge number of stories for viewers back home, and interviewed almost every Hollywood star. He became a US citizen in 2008, and is currently covering the US presidential election. Peter, thank you for joining me. It’s great to be here, thank you. And very kind that you’re a bit of a fan of the podcast before you agreed to come on! I love the podcast, yes! I’m a bit of a media geek, so I love hearing the stories and I especially like hearing people that I know and that I worked with. Peter Dixon was great, we worked on Steve Wright, of course, many moons ago. He’s a legend, isn’t he? He is a legend. They’re both legends. And Torin Douglas as well, that was one of the ones you listened to. Yes, I mean, the media talk especially and the insider stuff, of course the BBC stuff, dealing with stories, and we all have these things in common; how we interact with people in the real world and Hollywood and deadlines and all that kind of thing. -

Have 24 Hour TV News Channels Had Their Day?

9/21/2018 Have 24-hour TV news channels had their day? | Media | The Guardian Have 24hour TV news channels had their day? The former director of BBC News, Richard Sambrook, and its ex-head of strategy, Sean McGuire, argue that digital technology has left rolling news channels outmoded Richard Sambrook and Sean McGuire Mon 3 Feb 2014 14.14 GMT It's January 1991. Peter Arnett is reporting from the Al-Rashid hotel in Baghdad as the first air strikes of the Gulf war hit the Iraqi capital. He's live on CNN. Audiences around the world are gripped. The 24-hour news channel has come of age. Fast forward to January 2011. Tahrir Square, Egypt. Citizen journalism ensures that pictures of demonstrations and the resulting crackdown are beamed directly to a global audience. https://www.theguardian.com/media/2014/feb/03/tv-24-hour-news-channels-bbc-rolling 1/8 9/21/2018 Have 24-hour TV news channels had their day? | Media | The Guardian Protests in Cairo's Tahrir Square were brought to us by citizen journalism. Photograph: Mohammed Abed/AFP/Getty Images The next year, 8 million people tune in live to YouTube to watch Felix Baumgartner jump from outer space. Many times that audience log in to watch it over the next few days. Spin on to April 2013 and the Boston marathon bombings. CNN stumbles in front of a huge and anxious audience claiming an arrest had been made when it hadn't. Live blogging – with its speed, transparency of sources, and pared-down format – comes into its own. -

Stephen Cole

Stephen Cole Writer and broadcaster Media Masters – August 3, 2017 Listen to the podcast online, visit www.mediamasters.fm Welcome to Media Masters, a series of one to one interviews with people at the top of the media game. Today I’m joined by the international broadcast journalist Stephen Cole, chairman of the Institute of Diplomacy and Business, and CEO of communications business Cole Productions. Stephen has been part of the launch presenting team for four major news networks – Sky News, CNN International, BBC World and Al-Jazeera English. He also worked at the BBC where he founded the technology programme Click Online, and stepped into the breach to cover the nightly news during the staff strike action in 2005. Stephen, thank you for joining me. Thank you Paul. Good to see you. You’re the consummate TV News anchorman. Can you beat that rush of breaking a story on air? Do you miss it? No I don’t, because I’ve done it for a long time. But I don’t think there’s any real buzz that I get that is the same as when a story starts to break and you’re on your own in a studio. You don’t have a script. You don’t know where you’re going, because you don’t know where the story’s going, and nobody in the gallery can help you. You are exposed; you are in the headlights, you are on your own. And that I find so exciting. And the first time I knew I could do that was at Sky News in ‘89. -

30Th-31St JANUARY 2013 HILTON LONDON TOWER BRIDGE HOTEL

30th-31st JANUARY 2013 HILTON LONDON TOWER BRIDGE HOTEL HOSTED BY: SPONSORED BY: 1 TELECOMFINANCE WOULD LIKE TO EXTEND A 6 Programme WARM WELCOME TO ALL DELEGATES, SPEAKERS AND SPONSORS ATTENDING OUR EIGHTH ANNUAL 8 Awards Shortlist TELECOMFINANCE CONFERENCE IN LONDON 9 Sponsors We’d like to welcome all of our Bright spots in the sector include cable, delegates, speakers and sponsors to which already boasts FTTH, towercos, the TelecomFinance 2013 Conference, whose innovative business model has two days of networking, learning proven to be both efficient and financially 13 Speakers and debating with peers in the global beneficial, and data centres, thanks to telecoms and technology industry. revenues that increase in tandem with data traffic. 2012 was another tough year, marked however by a necessary admission by We are looking forward to hearing telecoms operators that soaring debt different views from you all on how the levels and continued falling revenue telecoms operator of the future will look. required tough decisions like selling hard Will it compete on the basis of brand won assets, overhauling infrastructure- rather than network, or will investors focused business models and partnering demand a safer utility approach? with rivals. Enjoy the conference. This year, European operators especially will try to convince regulators to favour vital investment in new networks over competition, and perhaps consider radical moves such as shared international and intra-national networks – spurring smaller players to warn of a return to the -

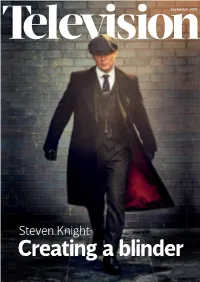

Steven Knight Creating a Blinder CAPTURE the ESSENCE of a NATION

September 2019 Steven Knight Creating a blinder CAPTURE THE ESSENCE OF A NATION A collection of music inspired by Japan, from traditional instruments to modern J-Pop AVAILABLE FOR LICENCE AT AUDIONETWORK.COM/DISCOVER/SOUNDSOFJAPAN FIND OUT MORE: Rebecca Hodges [email protected] (0)207 566 1441 Journal of The Royal Television Society September 2019 l Volume 56/8 From the CEO The man who wrote ITV Chief Executive Carolyn McCall, over licence fees for the over-75s, Britain’s answer to the convention’s chair, outlines her which provides a lot of context. HBO’s Boardwalk thinking for the RTS conference in an Mathew Horsman’s piece on the con- Empire, the brilliant interview with Television. She explains, test to own the on-demand market is crime drama Peaky among other things, how a panel of typically well-informed and incisive. Blinders, is the subject consumers will be a key part of this In keeping with the accent on Cam- of this month’s cover year’s Cambridge agenda. bridge, this month’s Our Friend column story. Andrew Billen interviewed We also profile one of the conven- has an East Anglian flavour. Chris Page Steven Knight and found that his life tion’s US speakers, Linda Yaccarino, will need no introduction to viewers in story really is stranger than fiction. head of advertising and partnerships the ITV Anglia region. His sometimes Don’t miss this riveting read. In my at NBCUniversal. Linda is less well maverick approach to weather fore- opinion, it is one of Andrew’s best known in the UK than she is across casting is often a talking point in his ever interviews for Television. -

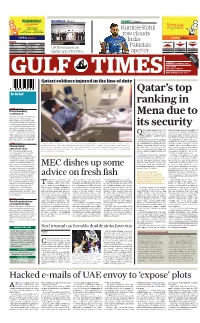

Qatar's Top Ranking in Mena Due to Its Security

BUSINESS | Page 1 SPORT | Page 1 Kumble-Kohli row clouds India- INDEX DOW JONES QE NYMEX QATAR 2-7, 24 COMMENT 22, 23 REGION 8 BUSINESS 1-5, 12-16 Pakistan UK fi rms keen on 21,203.00 9,901.38 47.66 ARAB WORLD 8, 9 CLASSIFIED 6-12 +71.00 -162.26 -0.70 INTERNATIONAL 10 – 21 SPORTS 1 – 8 Qatar opportunities opener +0.34% -1.61% -1.45% Latest Figures published in QATAR since 1978 SUNDAY Vol. XXXVIII No. 10474 June 4, 2017 Ramadan 9, 1438 AH GULF TIMES www. gulf-times.com 2 Riyals Qatari soldiers injured in the line of duty Qatar’s top In brief ranking in QATAR | Reaction Kabul bombing condemned Mena due to Qatar has strongly condemned the bombing in the Afghan capital of Kabul, which resulted in the death and injury of a number of people. In a statement yesterday the Ministry of Foreign Aff airs reiterated Qatar’s its security firm position rejecting violence and terrorism regardless of motives or atar’s high ranking in the 2017 ing the internal and external aff airs of reasons. The statement expressed Global Peace Index (GPI) re- countries such as political stability, ex- Qatar’s condolences to the families Qfl ects the country’s security tent of crime in society, level of respect of the victims, the government and status, the Ministry of Interior (MoI) for human rights, terrorist crimes on the Afghan people, and wished the has stressed. the territory of the State, the extent injured speedy recovery. Page 19 For the ninth year in a row, Qatar has of participation in support of peace- been ranked as the most peaceful coun- keeping forces, military capabilities of QATAR | Weather Six Qatari soldiers were injured in the course of their duty as part of the Qatari contingent defending the southern border of try in the Middle East and North Africa the State, spread of corruption and the the sisterly Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, the Directorate of Moral Guidance at the Ministry of Defence announced. -

Saturday 14 November, the Lancaster, London Welcome

SATURDAY 14 NOVEMBER, THE LANCASTER, LONDON WELCOME I am often asked what makes a Special Day The Willow Ball means so much to us special? What is it about this one day that means both. Every other activity throughout so much to so many? It is impossible to provide a the year centres around sport, single response. Each Special Day is a bespoke comedy or art but the Ball always experience tailor-made to meet the beneficiary’s brings us back to the core of Willow needs so its meaning and its impact is totally unique and our Special Days. This is where to them and their loved ones. Tonight we aim to our hearts and minds are always highlight just a few of the reasons why a Special focused. We read the thank you Day sparkles. Individual testimonies can be read in letters from our beneficiaries, we see this programme and feature in tonight’s activities. their photographs and we share their And, if you are left in any doubt, Doun, the husband experiences. Life is unfair, young of one of our beneficiaries, Ting, joins us this evening adults should not have to live with to share her Special Day story and introduce more the difficult realities of life threatening Special Day stories in our new Willow film. illnesses. But, while they do, Willow will be here to provide a little normality, a day of joy and a bank of positive memories for them Willow is the only national charity offering quality of life and quality of time and their families through our Special Days. -

Annual Repor T and Accounts 2005/2006

BBC Annual Report and Accounts ReportAnnual and BBC 2005/2006 British Broadcasting Corporation Broadcasting House London W1A 1AA bbc.co.uk Annual Repor t and © BBC 2006 Accounts 2005/2006 Purpose, vision and values The BBC’s purpose is to enrich people’s lives with programmes and services that inform, educate and entertain The BBC’s vision is to be the most creative organisation in the world Values I Trust is the foundation of the BBC: we are independent, impartial and honest I Audiences are at the heart of everything we do I We take pride in delivering quality and value for money I Creativity is the lifeblood of our organisation I We respect each other and celebrate our diversity so that everyone can give their best I We are one BBC: great things happen when we work together Contents 2 Chairman’s statement 4 Director-General’s report 6 The BBC now and in the future 10 Board of Governors 12 Executive Board 14 Governors’ review of objectives 22 The BBC at a glance Governors’ review of services 24 Television 32 Radio 40 New Media 46 News 50 BBC World Service & Global News 54 Nations & Regions 58 Governors’ review of commercial activities 60 Being accountable and responsible 68 Performance against Statements of Programme Policy commitments 2005/2006 76 Compliance 92 Financial review 95 Financial statements 140 Broadcasting facts and figures 151 Getting in touch with the BBC 152 Other information BBC Annual Report and Accounts 2005/2006 1 Chairman’s statement This is the last annual report from the The main function of the Trust will be to BBC Board of Governors, which is to ensure that licence fee payers’ expectations be replaced under the new draft Royal of the BBC are fulfilled in terms of the Charter by the BBC Trust. -

Annual Repor T and Accounts 2005/2006

BBC Annual Report and Accounts ReportAnnual and BBC 2005/2006 British Broadcasting Corporation Broadcasting House London W1A 1AA bbc.co.uk Annual Repor t and © BBC 2006 Accounts 2005/2006 Purpose, vision and values The BBC’s purpose is to enrich people’s lives with programmes and services that inform, educate and entertain The BBC’s vision is to be the most creative organisation in the world Values I Trust is the foundation of the BBC: we are independent, impartial and honest I Audiences are at the heart of everything we do I We take pride in delivering quality and value for money I Creativity is the lifeblood of our organisation I We respect each other and celebrate our diversity so that everyone can give their best I We are one BBC: great things happen when we work together Contents 2 Chairman’s statement 4 Director-General’s report 6 The BBC now and in the future 10 Board of Governors 12 Executive Board 14 Governors’ review of objectives 22 The BBC at a glance Governors’ review of services 24 Television 32 Radio 40 New Media 46 News 50 BBC World Service & Global News 54 Nations & Regions 58 Governors’ review of commercial activities 60 Being accountable and responsible 68 Performance against Statements of Programme Policy commitments 2005/2006 76 Compliance 92 Financial review 95 Financial statements 140 Broadcasting facts and figures 151 Getting in touch with the BBC 152 Other information BBC Annual Report and Accounts 2005/2006 1 Chairman’s statement This is the last annual report from the The main function of the Trust will be to BBC Board of Governors, which is to ensure that licence fee payers’ expectations be replaced under the new draft Royal of the BBC are fulfilled in terms of the Charter by the BBC Trust. -

The BBC Executive's Review and Assessment 2009-10

THE BBC EXECUTIVE’S REVIEW AND ASSESSMENT In addition to the information given in the following pages, you can find out how we performed last year against a whole range of other commitments – including our Statements of Programme Policy, the WOCC, Ofcom quotas and access services targets – in the Performance Against Public Commitments pdf available in the download section at www.bbc.co.uk/annualreport. Executive cover image: Photo shows Doctor Who’s TARDIS: let the BBC take you on a journey to where you want to go – sharing new places and new possibilities. PART 2 GOVERNANCE 2-76 EXECUTIVE BOARD BBC EXECUTIVE 2-78 SUMMARY GOVERNANCE OVERVIEW REPORT 2-2 UN DERSTANDING FINANCIAL STATEMENTS THE BBC’S FINANCES 2-86 FINANCIAL OVERVIEW 2-4 DIRECTOR-GENERAL’S 2-94 BEYOND BROADCASTING FOREWORD 2-95 SUMMARY FINANCIAL 2-10 PUTTING QUALITY FIRST STATEMENT PERFORMANCE 2-95 INDEPENDENT AUDITOR’S 2-14 THE BBC’S PURPOSES STATEMENT 2-16 RADIO 2-96 SUMMARY CONSOLIDATED 2-24 JOURNALISM INCOME STATEMENT 2-32 TELEVISION 2-97 SUMMARY CONSOLIDATED 2-40 FUTURE MEDIA & TECHNOLOGY BALANCE SHEET 2-46 ENSURING FUTURE QUALITY 2-97 SUMMARY CONSOLIDATED MANAGING THE BUSINESS CASH FLOW STATEMENT 2-60 OPERATIONS 2-98 NOTES TO THE SUMMARY 2-66 BBC’S ROLE IN A WIDER FINANCIAL STATEMENTS MEDIA LANDSCAPE 2-104 GLOSSARY 2-72 RISKS AND OPPORTUNITIES CONTACT US CREDITS 2 This year the individual licence fee was £142.50. Gross efficiency savings £m The monthly charge per licence fee was: 2,000 Projected 2bn548 £1.35 (11%) 1,500 £0.67 480 (6%) 1,000 £2.01 404 (17%) Television 500 £7.85 Radio 316 (66%) Online 237 0 Other 08/09 09/10 10/11 11/12 12/13 Total Through the efficient and effective collection of the licence fee, by reducing the cost of running how we manage our business year-on-year, and by selling and licensing programmes and content assets to companies in the UK and abroad, we strive to increase the amount of money available to invest in delivering the right portfolio of programmes and services for UK audiences. -

Sam Taylor Executive Editor, BBC News Channel Media Masters – May 11, 2018 Listen to the Podcast Online, Visit

Sam Taylor Executive Editor, BBC News Channel Media Masters – May 11, 2018 Listen to the podcast online, visit www.mediamasters.fm Welcome to Media Masters, a series of one to one interviews with people at the top of the media game. Today, I’m joined by Sam Taylor, executive editor for BBC News Channel and BBC News at One. After starting his career as a trainee in 1997, Sam rose up the Beeb’s news division and is now responsible for commissioning and innovation, establishing new forms of real time online reporting, and a strategy for younger audiences. As executive editor, he has led the BBC’s coverage of the EU referendum, the election of President Donald Trump, and international terror. Sam, thank you for joining me. Nice to see you. So, Sam, executive editor for BBC News Channel and News at One. What does the job involve? Are you basically the guy who runs News Channel? I suppose that’s right, yes. My joB has been through several variations in the five years or so I’ve been doing some of it, and then other things, and it’s changed around, as you do with these things, but I started off as what was called the controller of the BBC News Channel at the time. That sounds pretty good! Yes. And I think this joB is Basically the same as the executive editor. So we’ve regrouped it a few times, changed things around a little bit as we’ve looked at how we integrate with digital, but yes, Basically I look after News Channel both on the day editorial, and also the strategy and the programming that we run every day.