Full Issue University of New Mexico Press

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Old Humphrey's Walks in London and Its Neighbourhood (1854)

Victor i an 914.21 0L1o 1854 Joseph Earl and Genevieve Thornton Arlington Collection of 19th Century Americana Brigham Young University Library BRIGHAM YOUNG UNIVERSITY 3 1197 22902 8037 OLD HUMPHREY'S WALKS IN LONDON AND ITS NEIGHBOURHOOD. BY THE AUTHOR OP "OLD HUMPHREY'S OBSERVATIONS"—" ADDRESSES 1"- "THOUGHTS FOR THE THOUGHTFUL," ETC. Recall thy wandering eyes from distant lands, And gaze where London's goodly city stands. FIFTH EDITION. NEW YORK: ROBERT CARTER & BROTHERS, No. 28 5 BROADWAY. 1854. UOPB CONTENTS Pagt The Tower of London 14 Saint Paul's Cathedral 27 London, from the Cupola of St. Paul's .... 37 The Zoological Gardens 49 The National Gallery CO The Monument 71 The Panoramas of Jerusalem and Thebes .... 81 The Royal Adelaide Gallery, and the Polytechnic Institution 94 Westminster Abbey Ill The Museum at the India Hcfuse 121 The Colosseum 132 The Model of Palestine, or the Holy Land . 145 The Panoramas of Mont Blanc, Lima, and Lago Maggiore . 152 Exhibitions.—Miss Linwood's Needle-work—Dubourg's Me- chanical Theatre—Madame Tussaud's Wax-work—Model of St. Peter's at Rome 168 Shops, and Shop Windows * 177 The Parks 189 The British Museum 196 . IV CONTENTS. Chelsea College, and Greenwich Hospital • • . 205 The Diorama, and Cosmorama 213 The Docks 226 Sir John Soane's Museum 237 The Cemeteries of London 244 The Chinese Collection 263 The River Thames, th e Bridges, and the Thames Tunnel 2TO ; PREFACE. It is possible that in the present work I may, with some readers, run the risk of forfeiting a portion of that good opinion which has been so kindly and so liberally extended to me. -

|||GET||| Superheroes and American Self Image 1St Edition

SUPERHEROES AND AMERICAN SELF IMAGE 1ST EDITION DOWNLOAD FREE Michael Goodrum | 9781317048404 | | | | | Art Spiegelman: golden age superheroes were shaped by the rise of fascism International fascism again looms large how quickly we humans forget — study these golden age Superheroes and American Self Image 1st edition hard, boys and girls! Retrieved June 20, Justice Society of America vol. Wonder Comics 1. One of the ways they showed their disdain was through mass comic burnings, which Hajdu discusses Alysia Yeoha supporting character created by writer Gail Simone for the Batgirl ongoing series published by DC Comics, received substantial media attention in for being the first major transgender character written in a contemporary context in a mainstream American comic book. These sound effects, on page and screen alike, are unmistakable: splash art of brightly-colored, enormous block letters that practically shout to the audience for attention. World's Fair Comics 1. For example, Black Panther, first introduced inspent years as a recurring hero in Fantastic Four Goodrum ; Howe Achilles Warkiller. The dark Skull Man manga would later get a television adaptation and underwent drastic changes. The Senate committee had comic writers panicking. Howe, Marvel Comics Kurt BusiekMark Bagley. During this era DC introduced the Superheroes and American Self Image 1st edition of Batwoman inSupergirlMiss Arrowetteand Bat-Girl ; all female derivatives of established male superheroes. By format Comic books Comic strips Manga magazines Webcomics. The Greatest American Hero. Seme and uke. Len StrazewskiMike Parobeck. This era saw the debut of one of the earliest female superheroes, writer-artist Fletcher Hanks 's character Fantomahan ageless ancient Egyptian woman in the modern day who could transform into a skull-faced creature with superpowers to fight evil; she debuted in Fiction House 's Jungle Comic 2 Feb. -

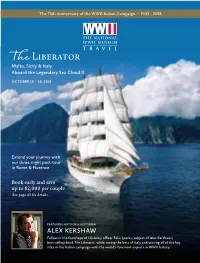

Alex Kershaw

The 75th Anniversary of the WWII Italian Campaign • 1943 - 2018 The Liberator Malta, Sicily & Italy Aboard the Legendary Sea Cloud II OCTOBER 19 – 28, 2018 Extend your journey with our three-night post-tour in Rome & Florence Book early and save up to $2,000 per couple See page 43 for details. FEATURING AUTHOR & HISTORIAN ALEX KERSHAW Follow in the footsteps of US Army officer Felix Sparks, subject of Alex Kershaw’s best-selling book The Liberator, while seeing the best of Italy and visiting all of the key sites in the Italian campaign with the world's foremost experts in WWII history. Dear friend of the Museum and fellow traveler, t is my great delight to invite you to travel with me and my esteemed colleagues from The National WWII Museum on an epic voyage of liberation and wonder – Ifrom the ancient harbor of Valetta, Malta, to the shores of Italy, and all the way to the gates of Rome. I have written about many extraordinary warriors but none who gave more than Felix Sparks of the 45th “Thunderbird” Infantry Division. He experienced the full horrors of the key battles in Italy–a land of “mountains, mules, and mud,” but also of unforgettable beauty. Sparks fought from the very first day that Americans landed in Europe on July 10, 1943, to the end of the war. He earned promotions first as commander of an infantry company and then an entire battalion through Italy, France, and Germany, to the hell of Dachau. His was a truly awesome odyssey: from the beaches of Sicily to the ancient ruins at Paestum near Salerno; along the jagged, mountainous spine of Italy to the Liri Valley, overlooked by the Abbey of Monte Cassino; to the caves of Anzio where he lost his entire company in what his German foes believed was the most savage combat of the war–worse even than Stalingrad. -

The Phenomenon of the Kentucky Burden in the Writing of James Still, Jesse Stuart, Allen Tate, and Robert Penn Warren

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Masters Theses Graduate School 5-2005 Their Old Kentucky Home: The Phenomenon of the Kentucky Burden in the Writing of James Still, Jesse Stuart, Allen Tate, and Robert Penn Warren Christian Leigh Faught University of Tennessee, Knoxville Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Faught, Christian Leigh, "Their Old Kentucky Home: The Phenomenon of the Kentucky Burden in the Writing of James Still, Jesse Stuart, Allen Tate, and Robert Penn Warren. " Master's Thesis, University of Tennessee, 2005. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes/4557 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by Christian Leigh Faught entitled "Their Old Kentucky Home: The Phenomenon of the Kentucky Burden in the Writing of James Still, Jesse Stuart, Allen Tate, and Robert Penn Warren." I have examined the final electronic copy of this thesis for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Master of Arts, with a major in English. Allison R. Ensor, Major Professor We have read this thesis and recommend its acceptance: Mary E. Papke, Thomas Haddox Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. -

Page 01 Aug 11.Indd

www.thepeninsulaqatar.com BUSINESS | 17 SPORT | 21 Central banks Pakistan ponder can’t just dial up line-up for England growth: Stevens finale at The Oval THURSDAY 11 AUGUST 2016 • 8 DHUL QA’DA 1437 • Volume 21 • Number 6885 2 Riyals thepeninsulaqatar @peninsulaqatar @peninsula_qatar PM meets Kuwait envoy Emir sends greetings Three regional to Ecuador President DOHA: Emir H H Sheikh Tamim bin Hamad Al Thani sent a cable of congratulations to President of the hospitals help Republic of Ecuador Rafael Cor- rea Delgado on the anniversary of his country’s Independence Day. reduce HGH rush Barwa awards ‘Dara A’ project to QDTC Cuban ( in Dukhan) hospitals are DOHA: Barwa Real Estate has bringing quality health care closer announced the award of the con- The demand for to the communities. So patients have struction of “Dara A” project to services at the to travel to Doha only for complex Qatar Development Company for care,” an HMC spokesman said yes- Trading & Contracting (QDTC) for Hamad General terday citing 2015 data on hospital a total value of QR115,9m and a visits. Last year, Al Wakra Hospi- duration of 18 months. The Dara A Hospital (HGH) has Prime Minister and Interior Minister H E Sheikh Abdullah bin Nasser bin Khalifa Al Thani with Ambassador also increased as tal recorded the highest number of project is located in the Northern visits at its Outpatient Department of Kuwait Mutib Saleh Al Mutawtah on the occasion of ending his tenure in Qatar. The Prime Minister part of Fox Hills in Lusail City. Qatar’s population (OPD). -

Talking Books Catalogue

Aaronovitch, Ben Rivers of London My name is Peter Grant and until January I was just another probationary constable in the Metropolitan Police Service. My only concerns in life were how to avoid a transfer to the Case Progression Unit and finding a way to climb into the panties of WPC Leslie May. Then one night, I tried to take a statement from a man who was already dead. Ackroyd, Peter The death of King Arthur An immortal story of love, adventure, chivalry, treachery and death brought to new life for our times. The legend of King Arthur has retained its appeal and popularity through the ages - Mordred's treason, the knightly exploits of Tristan, Lancelot's fatally divided loyalties and his love for Guenever, the quest for the Holy Grail. Adams, Jane Fragile lives The battered body of Patrick Duggan is washed up on a beach a short distance from Frantham. To complicate matters, Edward Parker, who worked for Duggan's father, disappeared at the same time. Coincidence? Mac, a police officer, and Rina, an interested outsider, don't think so. Adams,Jane The power of one Why was Paul de Freitas, a games designer, shot dead aboard a luxury yacht and what secret was he protecting that so many people are prepared to kill to get hold of? Rina Martin takes it upon herself to get to the bottom of things, much to the consternation of her friend, DI McGregor. ADICHIE, Chimamanda Ngozi Half of a Yellow Sun The setting is the lead up to and the course of Nigeria's Biafra War in the 1960's, and the events unfold through the eyes of three central characters who are swept along in the chaos of civil war. -

NEDOR HEROES! $ NEDOR HEROES! In8 Th.E9 U5SA

Roy Tho mas ’Sta nd ard Comi cs Fan zine OKAY,, AXIS—HERE COME THE GOLDEN AGE NEDOR HEROES! $ NEDOR HEROES! In8 th.e9 U5SA No.111 July 2012 . y e l o F e n a h S 2 1 0 2 © t r A 0 7 1 82658 27763 5 Vol. 3, No. 111 / July 2012 Editor Roy Thomas Associate Editors Bill Schelly Jim Amash Design & Layout Jon B. Cooke Consulting Editor John Morrow FCA Editor P.C. Hamerlinck Comic Crypt Editor Michael T. Gilbert Editorial Honor Roll Jerry G. Bails (founder) Ronn Foss, Biljo White, Mike Friedrich Proofreaders Rob Smentek, William J. Dowlding Cover Artist Shane Foley (after Frank Robbins & John Romita) Cover Colorist Tom Ziuko With Special Thanks to: Deane Aikins Liz Galeria Bob Mitsch Contents Heidi Amash Jeff Gelb Drury Moroz Ger Apeldoorn Janet Gilbert Brian K. Morris Writer/Editorial: Setting The Standard . 2 Mark Austin Joe Goggin Hoy Murphy Jean Bails Golden Age Comic Nedor-a-Day (website) Nedor Comic Index . 3 Matt D. Baker Book Stories (website) Michelle Nolan illustrated! John Baldwin M.C. Goodwin Frank Nuessel Michelle Nolan re-presents the 1968 salute to The Black Terror & co.— John Barrett Grand Comics Wayne Pearce “None Of Us Were Working For The Ages” . 49 Barry Bauman Database Charles Pelto Howard Bayliss Michael Gronsky John G. Pierce Continuing Jim Amash’s in-depth interview with comic art great Leonard Starr. Rod Beck Larry Guidry Bud Plant Mr. Monster’s Comic Crypt! Twice-Told DC Covers! . 57 John Benson Jennifer Hamerlinck Gene Reed Larry Bigman Claude Held Charles Reinsel Michael T. -

Singalong Songs Alles Kampvuurmuziek

Singalong Songs Alles Kampvuurmuziek Terug naar inhoudsopgave 1 Singalong Songs Alles Kampvuurmuziek --- Inhoudsopgave --- 26. Bill Withers - Ain't No Sunshine ........................................ 37 27. Earth Wind & Fire - Fantasy .............................................. 38 28. Bob Marley & The Wailers - No Woman No Cry ............. 39 29. Neil Young - Like A Hurricane .......................................... 40 30. Pointer Sisters – Fire .......................................................... 41 1. The Mamas & The Papas - California Dreamin' ................... 9 31. Grease – You’re the one that I want ................................... 42 2. Stand by me - Ben King ...................................................... 10 32. Meat Loaf - Paradise By The Dashboard Light ................. 43 3. Janis Joplin - Me and Bobby McGee .................................. 11 33. Soft Cell - Tainted Love ..................................................... 47 4. Johnny Cash - Ring Of Fire ................................................ 12 34. Golden Earring - When The Lady Smiles .......................... 48 5. Creedence Clearwater Revival - Proud Mary ..................... 13 35. Janis Ian - The Other Side of the Sun ................................. 49 6. Little Richard - Tutti Frutti ................................................. 14 36. George Michael - I knew you were waiting for me ........... 50 7. Jerry Lee Lewis – Great Balls Of Fire ................................ 15 37. George Michael – Faith ..................................................... -

Ye Intruders Beware: Fantastical Pirates in the Golden Age of Illustration

YE INTRUDERS BEWARE: FANTASTICAL PIRATES IN THE GOLDEN AGE OF ILLUSTRATION Anne M. Loechle Submitted to the faculty of the University Graduate School in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of the History of Art Indiana University November 2010 Accepted by the Graduate Faculty, Indiana University, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Doctoral Committee _________________________________ Chairperson, Sarah Burns, Ph.D. __________________________________ Janet Kennedy, Ph.D. __________________________________ Patrick McNaughton, Ph.D. __________________________________ Beverly Stoeltje, Ph.D. November 9, 2010 ii ©2010 Anne M. Loechle ALL RIGHTS RESERVED iii Acknowledgments I am indebted to many people for the help and encouragement they have given me during the long duration of this project. From academic and financial to editorial and emotional, I was never lacking in support. I am truly thankful, not to mention lucky. Sarah Burns, my advisor and mentor, supported my ideas, cheered my successes, and patiently edited and helped me to revise my failures. I also owe her thanks for encouraging me to pursue an unorthodox topic. From the moment pirates came up during one of our meetings in the spring of 2005, I was hooked. She knew it, and she continuously suggested ways to expand the idea first into an independent study, and then into this dissertation. My dissertation committee – Janet Kennedy, Patrick McNaughton, and Beverly Stoeltje – likewise deserves my thanks for their mentoring and enthusiasm. Other scholars have graciously shared with me their knowledge and input along the way. David M. Lubin read a version of my third chapter and gave me helpful advice, opening up to me new ways of thinking about Howard Pyle in particular. -

Race War Draft 2

Race War Comics and Yellow Peril during WW2 White America’s fear of Asia takes the form of an octopus… The United States Marines #3 (1944) Or else a claw… Silver Streak Comics #6 (Sept. 1940)1 1Silver Streak #6 is the first appearance of Daredevil Creatures whose purpose is to reach out and ensnare. Before the Octopus became a symbol of racial fear it was often used in satirical cartoons to stoke a fear of hegemony… Frank Bellew’s illustration here from 1873 shows the tentacles of the railroad monopoly (built on the underpaid labor of Chinese immigrants) ensnaring our dear Columbia as she struggles to defend the constitution from such a beast. The Threat is clear, the railroad monopoly is threating our national sovereignty. But wait… Isn’t that the same Columbia who the year before… Yep… Maybe instead of Columbia frightening away Indigenous Americans as she expands west, John Gast should have painted an octopus reaching out across the continent grabbing land away from them. White America’s relationship with hegemony has always been hypocritical… When White America views the immigration of Chinese laborers to California as inevitably leading to the eradication of “native” White Americans, it can only be because when White Americans themselves migrated to California they brought with them an agenda of eradication. In this way White European and American “Yellow Peril” has largely been based on the view that China, Japan, and India represent the only real threats to white colonial dominance. The paranoia of a potential competitor in the game of rule-the-world, especially a competitor perceived as being part of a different species of humans, can be seen in the motivation behind many of the U.S.A.’s military involvement in Asia. -

Item ID Number 01570 Color D Number of Images 192 Descrlpton Notes

Item ID Number 01570 Aether Lathrop, George D. Corporate Author United States Air Force School of Aerospace Medicine, Report/Article Title Epidemiologic Investigation of Health Effects in Air Force Personnel Following Exposure to Herbicides: Study Protocol Journal/Book Title Yeer MODth/Day December Color D Number of Images 192 Descrlpton Notes Wednesday, May 23, 2001 Page 1571 of 1608 ALV1N L. YOUNG, Major, USAF Consultant, Environmental Sciences Report SAM-TR- 82-44 EPIDEMIOLOGIC INVESTIGATION OF HEALTH EFFECTS IN AIR FORCE PERSONNEL FOLLOWING EXPOSURE TO HERBICIDES: STUDY PROTOCOL George D. Lathrop, Colonel, USAF, MC William H. Wolfe, Lieutenant Colonel, USAF, MC Richard A. Albanese, M.D. Patricia M. Mpynahan, Colonel, USAF, NC December 1982 Initial Report for Period October 1978 - December 1982 Approved for public release; distribution unlimited. Prepared for: The Surgeon General United States Air Force Washington, D.C. 20314 USAF SCHOOL OF AEROSPACE MEDICINE Aerospace Medical Division (AFSC) Brooks Air Force Base; Texas 78235 NOTICES This initial report was submitted by personnel of the Epidemiology Division and the Data Sciences Division, USAF School of Aerospace Medicine, Aerospace Medical Division, AFSC, Brooks Air Force Base, Texas, under job order 2767-00-01. When Government drawings, specifications, or other data are used for any purpose other than in connection with a definitely Government-related procure- ment, the United States Government incurs no responsibility or any obligation whatsoever. The fact that the Government may have formulated or in any way supplied the said drawings, specifications, or other data, is not to be regarded by implication, or otherwise in any manner construed, as licensing the holder, or any other person or corporation; or as conveying any rights or permission to manufacture, use, or sell any patented invention that may in any way be related thereto. -

Caves of Missouri

CAVES OF MISSOURI J HARLEN BRETZ Vol. XXXIX, Second Series E P LU M R I U BU N S U 1956 STATE OF MISSOURI Department of Business and Administration Division of GEOLOGICAL SURVEY AND WATER RESOURCES T. R. B, State Geologist Rolla, Missouri vii CONTENT Page Abstract 1 Introduction 1 Acknowledgments 5 Origin of Missouri's caves 6 Cave patterns 13 Solutional features 14 Phreatic solutional features 15 Vadose solutional features 17 Topographic relations of caves 23 Cave "formations" 28 Deposits made in air 30 Deposits made at air-water contact 34 Deposits made under water 36 Rate of growth of cave formations 37 Missouri caves with provision for visitors 39 Alley Spring and Cave 40 Big Spring and Cave 41 Bluff Dwellers' Cave 44 Bridal Cave 49 Cameron Cave 55 Cathedral Cave 62 Cave Spring Onyx Caverns 72 Cherokee Cave 74 Crystal Cave 81 Crystal Caverns 89 Doling City Park Cave 94 Fairy Cave 96 Fantastic Caverns 104 Fisher Cave 111 Hahatonka, caves in the vicinity of 123 River Cave 124 Counterfeiters' Cave 128 Robbers' Cave 128 Island Cave 130 Honey Branch Cave 133 Inca Cave 135 Jacob's Cave 139 Keener Cave 147 Mark Twain Cave 151 Marvel Cave 157 Meramec Caverns 166 Mount Shira Cave 185 Mushroom Cave 189 Old Spanish Cave 191 Onondaga Cave 197 Ozark Caverns 212 Ozark Wonder Cave 217 Pike's Peak Cave 222 Roaring River Spring and Cave 229 Round Spring Cavern 232 Sequiota Spring and Cave 248 viii Table of Contents Smittle Cave 250 Stark Caverns 256 Truitt's Cave 261 Wonder Cave 270 Undeveloped and wild caves of Missouri 275 Barry County 275 Ash Cave