Wilderness Science in a Time of Change Conference—Volume 5: Wilderness Ecosystems, Threats, and Management; 1999 May 23–27;

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Helicopter-Supported Commercial Recreation Activities in Alaska

HELICOPTER-SUPPORTED COMMERCIAL RECREATION ACTIVITIES IN ALASKA Prepared for Alaska Quiet Rights Coalition Prepared by Nancy Welch Rodman, Welch & Associates and Robert Loeffler, Opus Consulting Funded by a grant from Alaska Conservation Foundation October 2006 Helicopter-Supported Commercial Recreation Activities in Alaska Helicopter-Supported Commercial Recreation Activities in Alaska TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive Summary.................................................................................................................. ES-1 1. Introduction ........................................................................................................................1-1 1.1. Purpose of this report...............................................................................................1-1 1.2. What is not covered by this report ...........................................................................1-1 2. Laws, Regulations and Policies..........................................................................................2-1 2.1. Legal Authority to Regulate.....................................................................................2-1 2.2. Strategies to Regulate Impacts.................................................................................2-5 2.3. Limitations on Authorities, Permit Terms, and Strategies.......................................2-7 2.4. Summary..................................................................................................................2-8 3. Types and Consumers of Helicopter-Supported -

Alaska Range

Alaska Range Introduction The heavily glacierized Alaska Range consists of a number of adjacent and discrete mountain ranges that extend in an arc more than 750 km long (figs. 1, 381). From east to west, named ranges include the Nutzotin, Mentas- ta, Amphitheater, Clearwater, Tokosha, Kichatna, Teocalli, Tordrillo, Terra Cotta, and Revelation Mountains. This arcuate mountain massif spans the area from the White River, just east of the Canadian Border, to Merrill Pass on the western side of Cook Inlet southwest of Anchorage. Many of the indi- Figure 381.—Index map of vidual ranges support glaciers. The total glacier area of the Alaska Range is the Alaska Range showing 2 approximately 13,900 km (Post and Meier, 1980, p. 45). Its several thousand the glacierized areas. Index glaciers range in size from tiny unnamed cirque glaciers with areas of less map modified from Field than 1 km2 to very large valley glaciers with lengths up to 76 km (Denton (1975a). Figure 382.—Enlargement of NOAA Advanced Very High Resolution Radiometer (AVHRR) image mosaic of the Alaska Range in summer 1995. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration image mosaic from Mike Fleming, Alaska Science Center, U.S. Geological Survey, Anchorage, Alaska. The numbers 1–5 indicate the seg- ments of the Alaska Range discussed in the text. K406 SATELLITE IMAGE ATLAS OF GLACIERS OF THE WORLD and Field, 1975a, p. 575) and areas of greater than 500 km2. Alaska Range glaciers extend in elevation from above 6,000 m, near the summit of Mount McKinley, to slightly more than 100 m above sea level at Capps and Triumvi- rate Glaciers in the southwestern part of the range. -

Park Summer Conditions Report DENALI STATE PARK ______9/24/2021

Park Summer Conditions Report DENALI STATE PARK ___________________________9/24/2021 Park Facility Conditions OPEN. RV campground will be closing on Tuesday 9/28. Reservations ended 9/15. K’esugi Ken Campground OPEN. Denali View South OPEN. Lower Troublesome Creek OPEN. Alaska Veterans Memorial OPEN. Campground will be closing on Tuesday 9/28. Byers Lake Campground OPEN. Denali View North Campground Trail Reports Trail is lightly snow covered. Curry Ridge Trail Some downed trees. Lower Troublesome Creek Trail Several downed trees. Upper Troublesome Creek Trail Trail is snow-covered with several downed trees due to recent heavy winds. Cascade Trail Trail is snow-covered with several downed trees due to recent heavy winds. Ermine Hill Trail Outlet Bridge on South End is Closed. Many downed trees. Backside of Lake very brushy. Byers Lake Loop Trail Be prepared for Winter conditions including snow and below freezing temps. Kesugi Ridge Trail Trail is snow-covered with several downed trees due to recent heavy winds. Little Coal Creek Trail Overall Conditions: CAUTION: Alaska State Parks is committed to keeping our public use cabins open for all to enjoy. We need your help! BRING YOUR OWN CLEANING SUPPLIES. CLEAN AND SANITIZE WHEN YOU ARRIVE FOR THE HEALTH AND SAFETY OF ALL. CLEAN AND SANITIZE WHEN YOU LEAVE. Public Use Cabins are not sanitized on a regular basis like our other Park facilities. Reminder: Open fires are only allowed in approved metal fire rings at developed facilities or on gravel bars of the Chulitna, Susitna, or Tokositna Rivers. Real time weather info at: Kesugi Ken Web Cam: http://dnr.alaska.gov/parks/units/matsu/kkwebcam/kkwebcam.htm Weather Station: www.wunderground.com/weather/us/ak/talkeetna/KAKTRAPP2 A $5 day-use fee or annual parking pass is required at most trailheads through the park. -

MOUNT Mckinley NATIONAL PARK ALASKA

UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR HUBERT WORK. SECRETARY NATIONAL PARK SERVICE STEPHEN T. MATHER, DIRECTOR RULES AND REGULATIONS MOUNT McKINLEY NATIONAL PARK ALASKA Courtesy Alaska Railroad MOUNT McKINLEY AND REFLECTION SEASON FROM JUNE 1 TO SEPTEMBER 15 U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE : 1927 Courtesy Bragaw'8 Studio, Anchorage, Alaska CARIBOU IN MOUNT McKINLEY NATIONAL PARK Courtesy Brogaw's Studio, Anchorage, Alaska AN ALASKAN DOG TEAM CONTENTS Pane General description 1 Glaciers . 2 Plant life 2 The mammals and birds of Mount McKinley National Park ", Fishing 1) Climate 9 Administration 12 Park season 12 How to reach the park 12 Roads and trails 13 Accommodations 14 Rules and regulations It! Government publications: General IS Other national parks 18 Authorized rates for public utilities 1!) ILLUSTRATIONS COVER Mount McKinley and reflection Front, Caribou.in Mount McKinley National Park Inside front An Alaskan dog team Inside front A male surf bird on his nest Inside back Mountain sheep at Double Mountain Inside hack Mount McKinley Outside back Lake on divide at Sanctuary River Outside back TEXT Map of Alaska showing national park and monuments 10,11 Map of Mount McKinley National Park 15 52087°—27 1 j THE NATIONAL PARKS AT A GLANCE [Number, 10; total area, 11,801 square miles] Area in National parks in Location square Distinctive characteristics order of creation miles Hot Sprints Middle Arkansas . 1M •10 hot springs possessing curative properties— 1832 Many hotels and hoarding houses—19 bath houses under Government supervision. Yellowstone Northwestern Wyo 3, 348 More geysers than in all rest of world together- 1872 ming. -

Denali National Park and Preserve

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Natural Resource Program Center Water Resources Stewardship Report Denali National Park and Preserve Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/NRPC/WRD/NRTR—2007/051 ON THE COVER Photograph: Toklat River, Denali National Park and Preserve (Guy Adema, 2007) Water Resources Stewardship Report Denali National Park and Preserve Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/NRPC/WRD/NRTR-2007/051 Kenneth F. Karle, P.E. Hydraulic Mapping and Modeling P.O. Box 181 Denali Park, Alaska 99755 September 2007 U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service Natural Resources Program Center Fort Collins, Colorado The Natural Resource Publication series addresses natural resource topics that are of interest and applicability to a broad readership in the National Park Service and to others in the management of natural resources, including the scientific community, the public, and the NPS conservation and environmental constituencies. Manuscripts are peer- reviewed to ensure that the information is scientifically credible, technically accurate, appropriately written for the intended audience, and is designed and published in a professional manner. The Natural Resources Technical Reports series is used to disseminate the peer-reviewed results of scientific studies in the physical, biological, and social sciences for both the advancement of science and the achievement of the National Park Service’s mission. The reports provide contributors with a forum for displaying comprehensive data that are often deleted from journals because of page limitations. Current examples of such reports include the results of research that addresses natural resource management issues; natural resource inventory and monitoring activities; resource assessment reports; scientific literature reviews; and peer reviewed proceedings of technical workshops, conferences, or symposia. -

Forest Health Conditions in Alaska 2020

Forest Service U.S. DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE Alaska Region | R10-PR-046 | April 2021 Forest Health Conditions in Alaska - 2020 A Forest Health Protection Report U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, State & Private Forestry, Alaska Region Karl Dalla Rosa, Acting Director for State & Private Forestry, 1220 SW Third Avenue, Portland, OR 97204, [email protected] Michael Shephard, Deputy Director State & Private Forestry, 161 East 1st Avenue, Door 8, Anchorage, AK 99501, [email protected] Jason Anderson, Acting Deputy Director State & Private Forestry, 161 East 1st Avenue, Door 8, Anchorage, AK 99501, [email protected] Alaska Forest Health Specialists Forest Service, Forest Health Protection, http://www.fs.fed.us/r10/spf/fhp/ Anchorage, Southcentral Field Office 161 East 1st Avenue, Door 8, Anchorage, AK 99501 Phone: (907) 743-9451 Fax: (907) 743-9479 Betty Charnon, Invasive Plants, FHM, Pesticides, [email protected]; Jessie Moan, Entomologist, [email protected]; Steve Swenson, Biological Science Technician, [email protected] Fairbanks, Interior Field Office 3700 Airport Way, Fairbanks, AK 99709 Phone: (907) 451-2799, Fax: (907) 451-2690 Sydney Brannoch, Entomologist, [email protected]; Garret Dubois, Biological Science Technician, [email protected]; Lori Winton, Plant Pathologist, [email protected] Juneau, Southeast Field Office 11175 Auke Lake Way, Juneau, AK 99801 Phone: (907) 586-8811; Fax: (907) 586-7848 Isaac Dell, Biological Scientist, [email protected]; Elizabeth Graham, Entomologist, [email protected]; Karen Hutten, Aerial Survey Program Manager, [email protected]; Robin Mulvey, Plant Pathologist, [email protected] State of Alaska, Department of Natural Resources Division of Forestry 550 W 7th Avenue, Suite 1450, Anchorage, AK 99501 Phone: (907) 269-8460; Fax: (907) 269-8931 Jason Moan, Forest Health Program Coordinator, [email protected]; Martin Schoofs, Forest Health Forester, [email protected] University of Alaska Fairbanks Cooperative Extension Service 219 E. -

Wildlife & Wilderness 2022

ILDLIFE ILDERNESS WALASKAOutstanding & ImagesW of Wild 2022Alaska time 9winner NATIONAL CALENDAR TM AWARDS An Alaska Photographers’An Alaska Calendar Photographers’ Calendar Eagle River Valley Sunrise photo by Brent Reynolds Celebrating Alaska's Wild Beauty r ILDLIFE ILDERNESS ALASKA W & W 2022 Sunday Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday The Eagle River flows through the Eagle River NEW YEAR’S DAY ECEMBER EBRUARY D 2021 F Valley, which is part of the 295,240-acre Chugach State Park created in 1970. It is the third-largest 1 2 3 4 1 2 3 4 5 state park in the entire United States. The 30 31 1 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 scenic river includes the north and south fork, 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 surrounded by the Chugach Mountains that 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 arc across the state's south-central region. • 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 The Eagle River Nature Center, a not-for 26 27 28 29 30 31 27 28 -profit organization, provides natural history City and Borough of Juneau, 1970 information for those curious to explore the Governor Tony Knowles, 1943- park's beauty and learn about the wildlife Fairbanks-North Star, Kenai Peninsula, and that inhabits the area. Matanuska-Susitna Boroughs, 1964 New moon 2 ● 3 4 5 6 7 8 Alessandro Malaspina, navigator, Sitka fire destroyed St. Michael’s 1754-1809 Cathedral, 1966 President Eisenhower signed Alaska Federal government sold Alaska Railroad Barry Lopez, author, 1945-2020 Robert Marshall, forester, 1901-1939 statehood proclamation, 1959 to state, 1985 Mt. -

2021-2022 Alaska Hunting Regulations

http://hunt.alaska.gov State restricted areas: 6 Tangle BLM & LakesDNR restrict Archaeological off-road veDistrict: - hiclesBLM designated to designated trails trails between MP 16 and MP 37. 1 Denali State Park: in Unit 13E within Denali State Park, hunting of include: Swede Lake Trail (MP 16) – 8.7 miles paralleling district boundary and bears over bait prohibited. leads into Dickey Lake Trail, Landmark Gap Trail South – branches to west for 6.2 miles, and Osar Lake (MP 37) – 8.2 miles to Osar Lake. DNR desig- nated trails include: Landmark Gap Trail North (MP 24.6) – 2.9 miles 2 Clearwater Creek Controlled Use Area: north of Denali Hwy, west of a to Landmark Gap Lake, Glacier Gap to Sevenmile Lake boundary 100 feet east of the length (MP 30.5) – 3 miles to Glacier Gap Lake continu- of the Maclaren Summit trail ing 4.9 miles to Sevenmile Lake, & Maclaren Summit Trailthis (MP 37) – 2.4 miles, that starts from the Denali authorization does not apply to Highway and heads north, hunting in the Clearwater Creek and including the Maclaren Controlled Use Area. Contact River drainage, east of and B L M (9 0 7 )8 2 2 -3 2 1 7 o rD N R including the eastern bank (907) 269-8503. drainages of the Susitna River downstream from and including the Susitna Glacier, 7 Delta Controlled Use Area: and the eastern bank of the Susitna that portion in 13B north of a line from the head of River, is closed to the use of any Canwell Glacier down the north side of glacier and Miller motorized vehicle for hunting, including Creek, along the divide separating the south side drainages the transportation of hunters, their hunting of Black Rapids Glacier, including Augustana Creek. -

Public Land Sources for Native Plant Materials in the Southcentral Alaska Region for Personal Landscaping Use

Public Land Sources for Native Plant Materials in the Southcentral Alaska Region for Personal Landscaping Use This paper describes where ANPS members and/or members of the public may collect native plant materials (seeds, cuttings for propagation, whole plants for transplant) from area public lands for use in home landscaping, floral arrangements or other related uses. This article DOES NOT address the collection of these materials for scientific or commercial use; collection of plant materials for non-personal use generally requires a permit from land management agencies prior to collection, if allowed at all. ANPS advises contacting the appropriate local land management office if you wish to collect material for scientific or commercial purposes. ANPS can also help advise non-profit scientific researchers about the practicality of making certain collections and/or assist with the gathering of materials; the Society can be reached at [email protected]. Other good sources of Native Plant Materials include via purchase from a number of local growers, commercial collectors and nurseries (see this website for a list of suppliers: http://plants.alaska.gov/nativeplantindex.htm), or by salvaging plants in advance of development projects on private land. A few words about management, boundaries and location Land ownership in the State of Alaska was relatively simple prior to 1959: land was either privately owned due to a homestead conveyance or similar grant, was withdrawn or otherwise reserved for some public purpose (i.e. national parks, military facilities, etc.), was included within a federal wildlife refuge or national forest, or was managed by the Bureau of Land Management / General Land Office as a part of the federal Public Domain. -

MOUNT Mckinley I Adolph Murie

I (Ie De/;,;;I; D·· 3g>' I \N ITHE :.Tnf,';AGt:: I GRIZZLIES OF !MOUNT McKINLEY I Adolph Murie I I I I I •I I I II I ,I I' I' Ii I I I •I I I Ii I I I I r THE GRIZZLIES OF I MOUNT McKINLEY I I I I I •I I PlEASE RETURN TO: TECHNICAL INfORMATION CENTER I f1r,}lVER SiRV~r.r Gs:t.!TER ON ;j1,l1uNAl PM~ :../,,;ICE I -------- --- For sale h~' the Super!u!p!u]eut of Documents, U.S. Goyernment Printing Office I Washing-ton. D.C. 20402 I I '1I I I I I I I I .1I Adolph Murie on Muldrow Glacier, 1939. I I I I , II I I' I I I THE GRIZZLIES I OF r MOUNT McKINLEY I ,I Adolph Murie I ,I I. I Scientific Monograph Series No. 14 'It I I I U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service Washington, D.C. I 1981 I I I As the Nation's principal conservation agency, the Department of the,I Interior has responsibility for most ofour nationally owned public lands and natural resources. This includes fostering the wisest use ofour land and water resources, protecting our fish and wildlife, preserving the environmental and cultural values of our national parks and historical places, and providing for the enjoyment of life through outdoor recre- I ation. The Department assesses our energy and mineral resources and works to assure that their development is in the best interests of all our people. The Department also has a major responsibility for American Indian reservation communities and for people who live in Island Ter- I ritories under U.S. -

Backcountry Camping Guide

National Park Service Denali National Park and Preserve U.S. Department of the Interior Backcountry Camping Guide Michael Larson Photo Getting Started Getting a Permit Leave No Trace and Safety This brochure contains information vital to the success of your Permits are available at the Backcountry Desk located in the Allow approximately one hour for the permit process, which Camping backcountry trip in Denali National Park and Preserve. The follow- Visitor Access Center (VAC) at the Riley Creek Entrance Area. consists of five basic steps: There are no established campsites in the Denali backcountry. Use ing paragraphs will outline the Denali backcountry permit system, the following guidelines when selecting your campsite: the steps required to obtain your permit, and some important tips for a safe and memorable wilderness experience. Step 1: Plan Your Itinerary tion that you understand all backcountry rules and regula- n Your tent must be at least 1/2-mile (1.3 km) away from the park road and not visible from it. Visit www.nps.gov/dena/home/hiking to preplan several alter- tions. Violations of the conditions of the permit may result in adverse impacts to park resources and legal consequences. Denali’s Trailless Wilderness native itineraries prior to your arrival in the park. Building flex- n Camp on durable surfaces whenever possible such as Traveling and camping in this expansive terrain is special. The lack ibility in your plans is very important because certain units may gravel river bars, and avoid damaging fragile tundra. of developed trails, bridges, or campsites means that you are free be unavailable at the time you actually wish to obtain your Step 4: Delineate Your Map to determine your own route and discover Denali for yourself. -

Appendix A. Glossary of Acoustic Terms

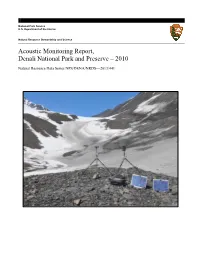

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Natural Resource Stewardship and Science Acoustic Monitoring Report, Denali National Park and Preserve – 2010 Natural Resource Data Series NPS/DENA/NRDS—2013/441 ON THE COVER A soundscape monitoring system collects data on the lateral moraine of the glacier which feeds Ohio Creek, on the south side of the Alaska Range in Denali National Park. NPS Photo by Jared Withers Acoustic Monitoring Report, Denali National Park and Preserve – 2010 Natural Resource Data Series NPS/DENA/NRDS—2013/441 Jared Withers Physical Scientist PO Box 9 Denali National Park, AK 99755 Davyd Betchkal Physical Science Technician PO Box 9 Denali National Park, AK 99755 January 2013 U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service Natural Resource Stewardship and Science Fort Collins, Colorado The National Park Service, Natural Resource Stewardship and Science office in Fort Collins, Colorado, publishes a range of reports that address natural resource topics. These reports are of interest and applicability to a broad audience in the National Park Service and others in natural resource management, including scientists, conservation and environmental constituencies, and the public. The Natural Resource Data Series is intended for the timely release of basic data sets and data summaries. Care has been taken to assure accuracy of raw data values, but a thorough analysis and interpretation of the data has not been completed. Consequently, the initial analyses of data in this report are provisional and subject to change. All manuscripts in the series receive the appropriate level of peer review to ensure that the information is scientifically credible, technically accurate, appropriately written for the intended audience, and designed and published in a professional manner.