Constitutional Law - Editorial Discretion Over Public Television - Muir V

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Rights of the Accused in Saudi Criminal Procedure

Loyola of Los Angeles International and Comparative Law Review Volume 15 Number 4 Symposium: Business and Investment Law in the United States and Article 5 Mexico 6-1-1993 The Rights of the Accused in Saudi Criminal Procedure Jeffrey K. Walker Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/ilr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Jeffrey K. Walker, The Rights of the Accused in Saudi Criminal Procedure, 15 Loy. L.A. Int'l & Comp. L. Rev. 863 (1993). Available at: https://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/ilr/vol15/iss4/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews at Digital Commons @ Loyola Marymount University and Loyola Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in Loyola of Los Angeles International and Comparative Law Review by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Loyola Marymount University and Loyola Law School. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Rights of the Accused in Saudi Criminal Procedure JEFFREY K. WALKER* I. INTRODUCTION In Islam, the only law is the law of God, and the law of God is the Shari'a. Literally "the way" or "the straight path," Shari'a is the civil and criminal law of Saudi Arabia2 and the Koran is the Saudi constitution. 3 "In Saudi Arabia, as in other Muslim countries, reli- gion and law are inseparable. Ethics, faith, jurisprudence, and practi- cality are so interdependent that it is impossible to study only Islamic religion or only Islamic law."' 4 Indeed, Islamic law is intended to serve as the expression of God's will. -

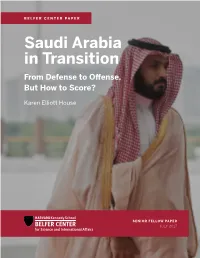

Saudi Arabia in Transition from Defense to Offense, but How to Score?

v BELFER CENTER PAPER Saudi Arabia in Transition From Defense to Offense, But How to Score? Karen Elliott House SENIOR FELLOW PAPER JULY 2017 Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs Harvard Kennedy School 79 JFK Street Cambridge, MA 02138 www.belfercenter.org Statements and views expressed in this report are solely those of the author and do not imply endorsement by Harvard University, Harvard Kennedy School, or the Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs. Design & Layout by Andrew Facini Cover photo and opposite page 1: Deputy Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman arrives at the Hangzhou Exhibition Center to participate in G20 Summit, Sunday, Sept. 4, 2016 in Hangzhou, China. (Etienne Oliveau/Pool Photo via AP) Copyright 2017, President and Fellows of Harvard College Printed in the United States of America BELFER CENTER PAPER Saudi Arabia in Transition From Defense to Offense, But How to Score? Karen Elliott House SENIOR FELLOW PAPER JUNE 2017 About the Author Karen Elliott House is a senior fellow at the Belfer Center and author of “On Saudi Arabia: Its People, Past, Religion, Fault Lines—and Future,” published by Knopf in 2012. During a 32 year career at The Wall Street Journal she served as diplomatic correspondent, foreign editor and finally as Publisher of the paper. She won a Pulitzer Prize for International Reporting in 1984 for her coverage of the Middle East. She is chairman of the RAND Corporation. Her April 2016 report on Saudi Arabia, “Uneasy Lies the Head that Wears a Crown,” can be found at the Belfer Center’s website: http://www.belfercenter.org/publication/uneasy-lies-head-wears-crown The author, above, in rural Jizan Province in April 2009 with an elderly farmer and some of his 35 children (from three wives) and 30 grandchildren. -

Fall 2005, Volume 31, No. 1

Fall 2005 Vol. 31 No. 1 FINDING COMMON GROUND IN THE MIDDLE EAST Zahira Kamal and Naomi Chazan to Speak at the UW sunday October 23, 2005 7:30 p.m. Kane Hall Room 130 University of Washington Free and open to the public Naomi Chazan Zahira Kamal N partnership with was Deputy Speaker and a Women. She was among the I Seattle’s Find Common member, among others, of the Founders and is presently the Ground organization, the Foreign Affairs and Defense Foreign Affairs Director of the Middle East Center will sponsor Committee. A professor of Palestinian Federation of an evening lecture on October political science (emerita) at the Women's Action, a member of 23, 2005 featuring Naomi Hebrew University of the Women's Affairs Technical Chazan and Zahira Kamal— Jerusalem, where she chaired Committee, and member on two extraordinary women who the Harry S Truman Research the boards of both Israeli and are working toward developing Institute for the Advancement Palestinian Networking and the progressive civil societies in of Peace, Naomi Chazan has Jerusalem Link, two Israel and Palestine. The written extensively on cooperating women's centers in evening event will be moderated comparative politics, African East and West Jerusalem. by KIRO Radio’s Dave Ross. politics, the Arab-Israel conflict, Sponsors of this event include: NAOMI CHAZAN now heads and women and peace. School of Theology and Ministry, Seattle University, Temple the School of Society and ZAHIRA KAMAL is currently De Hirsch Sinai, Politics at the Academic College the General Director of the The Episcopal Diocese of Western of Tel-Aviv-Yaffo after Directorate for Gender Washington, PNW Conference of the completing a year as the first Planning and Development at United Methodist Church – Peace Robert Wilhelm Fellow at the the Palestinian Ministry of with Justice Commission, University Temple United Methodist Center for International Studies Planning. -

Taleb Al-Ahmady Z

THE IMAGE OF SAUDI ARABIA IN THE BRITISH PRESS, with Particular Reference to Saudi Arabia's Islamic Mission. Taleb Al-Ahmady Z Submittedin accordancewith the requirementsfor the degreeof Ph.D. The University of Leeds Institute of CommunicationsStudies June 1995 The candidateconfirms that the work submittedis his own work and that appropriate credit hasbeen given where referencehas been madeto the work of others. 1 ABSTRACT Saudi The aim of this study is to trace the evolution of the image of Arabia in the British pressfrom the 1970's to the 1990's. During this period, the image which the press and its readershad of Saudi Arabia underwent a transformation. At the beginningof the 1970's, Saudi Arabia was perceivedas a distant, rather exotic, part of the Arabianpeninsula, much of a muchnesswith the other statesin the Gulf, a country about which little was or neededto be for known by British readers. It appearedto have no particular importance Britain, far less so than Egypt, Syria or Iraq which were seenas the countries of importanceand influence, for good or ill in the Middle East and within the Arab world. By the beginning of the 1990's, Saudi Arabia was by contrast in seen as a country which was of considerableimportance for Britain both particular and in a general,being of critical importancefor the West as a whole as the holder of both the largestoil reservesand having the largestlong-term oil production capacity in the world. It came to be presentedas economically important as a market for British exportsboth visible and invisible; a country in which a substantialnumber of British citizens worked and thus required the maintenanceof actively good diplomatic relations; a regional power; and, as at least one, if not now the most influential country in the affairs of the Arab world, when it choosesto exert its influence. -

FALLACIES by John Chancellor BERT R

DIRECTING MET: Kirk Browning FIRST AMENDMENT FREEDOMS: Bob Packwood THE DOCUDRAMA DILEMMA: Douglas Brode GRENADA AND THE MEDIA: John Chancellor IN AWORLD OF SUBTLETY, NUANCE, AND HIDDEN MEANING... "Wo _..,". - Ncyw4.7 T-....: ... ISN'T IT GOOD TO KNOW THERE'S SOMETHING THAT CAN EXPRESS EVE MOOD. The most evocative scenes in recent movies simply wouldn't ha tive without the film medium. The artistic versatility of Eastman color negative films lish any kind of mood or feeling, without losing believability. x Film is also the most flexible post -production medium. When yá ,;final negative imagery to videotape or to film, you can expect exception ds and feelings on Eastman color films, the best medium for your 'magi ó" Eastman film. It's looking Eastman Kodak Company, 1982 we think international TV Asahi Asahi National Broadcasting Co., Ltd. Celebrating a Decade of Innovation THE JOURNAL OF THE VOLUME XX NUMBER IV 1984 NATIONAL ACADEMY OF TELEVISION ARTS AND SCIENCES S'} TELEVI e \ QUATELY CONTENTS EDITORIAL BOARD EDITOR 7 VIDEO VERITÉ: DEFINING THE RICHARD M. PACK DOCUDRAMA by Douglas Brode CHAIRMAN HERMAN LAND 27 THE MEDIA AND THE INVASION MEMBERS OF GRENADA: FACTS AND ROYAL E. BLAKEMAN FALLACIES by John Chancellor BERT R. BRILLER JOHN CANNON 39 THERE WAS "AFTER" JOHN GARDEN BEFORE SCHUYLER CHAPIN THERE WAS ... by John O'Toole MELVIN A. GOLDBERG FREDERICK A. JACOBI 51 PROTECTING FIRST AMENDMENT ELLIN IvI00RE IN THE AGE OF THE MARLENE SANDERS FREEDOMS ALEX TOOGOOD ELECTRONIC REVOLUTION by Senator Bob Packwood 61 THE "CRANIOLOGY" OF THE 20th CENTURY: RESEARCH ON TELEVISION'S EFFECTS by Jib Fowles 75 CALLING THE SHOTS AT THE GRAPHICS DIRECTOR METROPOLITAN OPERA ROBERT MANSFIELD Kirk Browning -interviewed by Jack Kuney 93 REVIEW AND COMMENT: Three views of the MacNeil/Lehrer S. -

David Fanning, ‘Frontline’ Executive Producer, Graduate School of Journalism Wins 2004 Columbia Journalism Award Honors Distinguished Alumni

C olumbia U niversity RECORD May 19, 2004 9 David Fanning, ‘Frontline’ Executive Producer, Graduate School of Journalism Wins 2004 Columbia Journalism Award Honors Distinguished Alumni associate dean for academic PBS, initially with KOCE-TV in our distinguished alumni received the BY CAROLINE LADHANI affairs. Huntington, Calif. Graduate School of Journalism’s highest Fanning has been executive WGBH first hired Fanning in Falumni honor during the Alumni Associa- avid Fanning, executive producer of Frontline, which 1980 to develop a weekly pro- tion’s recent spring meeting. The awards, producer of PBS’ Front- originates from Boston PBS sta- gram called World. He then pro- which are presented annually, recognize jour- Dline, is the 2004 recipient tion WGBH, since the program’s duced and cowrote the docudra- nalistic excellence, a single outstanding jour- of the Columbia Journalism inception in 1983. The investiga- ma Death of a Princess with nalistic accomplishment or a contribution to Award, the highest honor award- tive documentary series has aired director Antony Thomas, and in journalism education. The following are this ed by the Columbia Graduate for 21 seasons and won major 1982, also with Thomas, the year’s winners. School of Journalism faculty. awards for broadcast journalism, Emmy Award-winning inves- The award recognizes singular among them, 29 Emmys, 16 tigative documentary Frank Ter- Kenneth Best, Journalism’67, is editor in journalistic performance in the duPont-Columbia University pil: Confessions of a Dangerous chief of West Africa’s first independent newspa- public interest. Awards and 11 Peabody Awards. Man. per, the Daily Observer, of Monrovia, Liberia. “David Fanning and his signa- More than a decade before his That same year, Fanning During that country’s Doe regime, Best was Best ture program, Frontline, have tenure began at Frontline, Fan- began developing Frontline for arrested and the offices of his newspaper burned turned a commitment to probing ning, a South Africa native, pro- WGBH, and soon after, two down. -

Saudi Moderation? Prince Muhammad Is on Shaky Ground

Saudi Moderation? Prince Muhammad Is on Shaky Ground by Dr. James M. Dorsey BESA Center Perspectives Paper No. 794, April 12, 2018 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY: Saudi Crown Prince Muhammad bin Salman has dazzled international media and public opinion by lifting some restrictions on women’s rights and holding out hope for the abolishment of others, vowing to return the kingdom to a vague form of moderate Islam that many believe is defined by the social reforms he has already implemented, and curbing the powers of the country’s ultra-conservative leadership. But his top-down approach to social change, which brushes aside Saudi history, rests on shaky ground. No doubt, Prince Muhammad’s recent reforms have benefitted women and created social opportunity with the introduction of modern forms of entertainment, including the opening this month of Saudi Arabia’s first cinema as well as concerts, theater, and dance performances. Anecdotal evidence testifies to the popularity of these moves, certainly among urban youth. But Prince Muhammad’s top-down approach to countering religious militancy rests on shaky ground. It involves rewriting history rather than owning up to responsibility, imposing his will on an ultra-conservative Sunni Muslim establishment whose change of heart in publicly backing him lacks credibility, and suppressing religious and secular voices who link religious and social change to political reform. Prince Muhammad has traced Saudi Arabia’s embrace of ultra-conservatism to 1979. That year, a popular revolt toppled the Shah and replaced Iran’s monarchy with an Islamic republic, and Saudi zealots took control of the Great Mosque in the holy city of Mecca. -

The Effects of Intercultural Communication on Viewers' Perceptions

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 280 101 CS 505 543 AUTHOR Pohl, Gayle M. TITLE The Effects of Intercultural Communication on Viewers' Perceptions. PUB DATE Apr 87 NOTE 37p.; Paper presented at the Joint Meeting of the Central States Speech Associatioe and the Southern Speech Communication Association St. Louis, MO, April 9-12, 1987). Best copy available. PUB TYPE Reports - Research/Technical(143) -- Speeches/Conference Papers (150) EDRS PRICE MF01/PCO2 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Attitude Change; *Audience AnalySiSi Cultural Awareness; Cultural Images; Culture Conflict; Foreign Countries; Higher Educationl *Intercultural Communication; *Mass Media Effects; Television Research; Undergraduate Students IDENTIFIERS Audience Research; *Audience Response; *DocudramaS; Muslims; Saudi Arabia ABSTRACT Three studies explored the impact of the controversial television docudrama "Death of a Princess" on viewers' attitudes, comprehension, and desire to continue viewing the film. Sixty students in undergraduate communication classes participated in Study I, which measured attitude change induced by the film, relative to the viewers' prior knowledge base. A different group of 60 communication undergraduates took part in Study II, in which thesame procedures were used, but attitude change relative to the viewers' level of religiosity was measured. Study III used a third group, 40 undergraduates enrolled, as were the others, in communication classes, to examine attitude change relative to personal evaluation of two concepts: "Saudi Arabia" and "Moslem." Each group was divided equally into those who reviewed the film and those who did not. Although it was hypothesized that viewing the docudrama would induce a more negative attitude toward Saudi Arabia, results indicated that a sweeping attitude change did not occur. Contrary to findings of previous research, men were found to be more persuadable thanwomen. -

1 the Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs

The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project BROOKS WRAMPELMEIER Interviewed by: Charles Stuart Kennedy Initial interview date: March 22, 2000 Copyright 2004 A ST TABLE OF CONTENTS Background Born and raised in Ohio Princeton Uni ersity; American Uni ersity of Beirut, Lebanon Entered Foreign Ser ice - 1956 State Department - FSI - Staff Aide 1956-195, U.S. Army, Fort .no/; Holabird, 0aryland 195, State Department - I1A - E/ecuti e Secretariat 1952-1959 Beirut, Lebanon - FSI - Arabic Language Training 1959-1960 1i il war 0arriage Language school En ironment Amman, 5ordan - Political Officer 1960-1964 En ironment 5ordan labor mo ement .ing Hussein 5ews 5erusalem Palestinians Nasserism Ambassador 0acomber 5eddah, Saudi Arabia - Political Officer 1964-1966 8emen ci il war Nasser En ironment Tra el Riyadh capital 1 Royal family 1ontacts State Department - INR - Egypt Analyst 1966-1962 196, Arab-Israeli war U.S. policy State Department - NEA - Arabian Peninsula Affairs 1962-19,4 0ilitary programs Persian :ulf claims Berber issues Persian :ulf states British withdrawal 8emen ci il war Oil embargo Saudi Arabia issues .hartoum assassination Lusaka, ;ambia - Political Officer/D10 19,4-19,6 .aunda Economy Political organizations Rhodesia 1ongressional isits .issinger isit En ironment 5ohns Hopkins School of Ad anced International Studies [SAIS? - 0ideast Studies 19,6-19,, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates - D10 19,,-1920 Federation Iran Oil Abu Dhabi Fund Security U.S. military presence .uwait - D10 1920-1922 IraA-Iran war Political changes Oil policies Stock market bust Bisas Intermarriage Bubiyan/Carbah islands 2 State Department - NEA - Arabian Peninsula Affairs - Deputy Director/Office Director 1922-1924 Operation Staunch Iran-IraA war U.S. -

Documentary Screens: Non-Fiction Film and Television

Documentary Screens Non-Fiction Film and Television Keith Beattie 0333_74117X_01_preiv.qxd 2/19/04 8:59 PM Page i Documentary Screens This page intentionally left blank 0333_74117X_01_preiv.qxd 2/19/04 8:59 PM Page iii Documentary Screens Non-Fiction Film and Television Keith Beattie 0333_74117X_01_preiv.qxd 2/19/04 8:59 PM Page iv © Keith Beattie 2004 All rights reserved. No reproduction, copy or transmission of this publication may be made without written permission. No paragraph of this publication may be reproduced, copied or transmitted save with written permission or in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, or under the terms of any licence permitting limited copying issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency, 90 Tottenham Court Road, London W1T 4LP. Any person who does any unauthorized act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages. The author has asserted his right to be identified as the author of this work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. First published 2004 by PALGRAVE MACMILLAN Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire RG21 6XS and 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10010 Companies and representatives throughout the world PALGRAVE MACMILLAN is the global academic imprint of the Palgrave Macmillan division of St. Martin’s Press, LLC and of Palgrave Macmillan Ltd. Macmillan® is a registered trademark in the United States, United Kingdom and other countries. Palgrave is a registered trademark in the European Union and other countries. ISBN 0–333–74116–1 hardback ISBN 0–333–74117–X paperback This book is printed on paper suitable for recycling and made from fully managed and sustained forest sources. -

U. S. F-15 Jet Fighter Sale to Saudi Arabia--Analysis

INFORMATION TO USERS This was produced from a copy of a document sent to us for microfilming. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1.The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced Into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting through an image and duplicating adjacent pages to assure you of complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a round black mark it is an indication that the film inspector noticed either blurred copy because of movement during exposure, or duplicate copy. Unless we meant to delete copyrighted materials that should not have been filmed, you will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame, if copyrighted materials were deleted you will find a target note listing the pages in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., is part of the material being photo graphed the photographer has followed a definite method in "sectioning" the material. It is customary to begin filming at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. If necessary, sectioning is continued again—beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. -

An Introductory History of British Broadcasting

An Introductory History of British Broadcasting ‘. a timely and provocative combination of historical narrative and social analysis. Crisell’s book provides an important historical and analytical introduc- tion to a subject which has long needed an overview of this kind.’ Sian Nicholas, Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television ‘Absolutely excellent for an overview of British broadcasting history: detailed, systematic and written in an engaging style.’ Stephen Gordon, Sandwell College An Introductory History of British Broadcasting is a concise and accessible history of British radio and television. It begins with the birth of radio at the beginning of the twentieth century and discusses key moments in media history, from the first wireless broadcast in 1920 through to recent developments in digital broadcasting and the internet. Distinguishing broadcasting from other kinds of mass media, and evaluating the way in which audiences have experienced the medium, Andrew Crisell considers the nature and evolution of broadcasting, the growth of broadcasting institutions and the relation of broadcasting to a wider political and social context. This fully updated and expanded second edition includes: ■ The latest developments in digital broadcasting and the internet ■ Broadcasting in a multimedia era and its prospects for the future ■ The concept of public service broadcasting and its changing role in an era of interactivity, multiple channels and pay per view ■ An evaluation of recent political pressures on the BBC and ITV duopoly ■ A timeline of key broadcasting events and annotated advice on further reading Andrew Crisell is Professor of Broadcasting Studies at the University of Sunderland. He is the author of Understanding Radio, also published by Routledge.