Chapter 41. Tunas and Billfishes Contributors

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rey, J.C. and Cort, J.L. 1978. Nota Sobre Los Primeros Resultados De La Campaña De Marcado De Túnidos Frente Al Litoral De Castellón

110 Rey, J.C. and Cort, J.L. 1978. Nota sobre los primeros resultados de la campaña de marcado de túnidos frente al litoral de Castellón. Bol. Inst. Esp. Oceanogr. 4 (3): 140–142 Rey, J.C. and Cort, J.L. 1981. Contribution à la connaissance de la migration des Scombridae en Méditerranée Occidentale. Rapp. P-V, Commn. Int. Explor. Scient. Mer Méditerr., 27: 97–98. Rey, J.C., Alot, E. and Ramos, A. 1984. Sinopsis biológica del bonito, Sarda sarda (Bloch), del Mediterráneo y Atlántico Este. Iccat, Coll. Vol. Sci. Pap. 20(2): 469–502. Rey, J.C., Alot, E. and Ramos, A. 1986. Growth of the Atlantic bonito (Sarda sarda Bloch, 1793) in the Atlantic and Mediterranean area of the Strait of Gibraltar. Inv. Pesq. 50 (2): 179–185. Robert, M. and Roesti. 1966. The Declining Economic Role of the Mediterranean Tuna Fishery American Journal of Economics and Sociology 25 (1), 77–90. Rodriguez Roda, J. 1966. Estudio de la bacoreta, Euthynnus alleteratus (Raf.) bonito, Sarda sarda (Bloch) y melva, Auxis thazard (Lac.), capturados por las almadrabas españolas. Inv. Pesq. 30: 247–292. Rodriguez Roda, J. 1981. Estudio de la edad y crecimiento del bonito, Sarda sarda (Block), de la costa sudatlantica de España. Inv. Pesq. 45(1):181–186. Rodriguez Roda, J. 1983. Edad y crecimiento de la melva, Auxis rochei (Risso), del Sur de España. Invest. Pesq. (Barc.), 47 (3): 397–402. Sabatés, A. and Recasens, L. 2001. Seasonal distribution and spawning of small tunas, Auxis rochei (Risso) and Sarda sarda (Bloch) in the northwestern Mediterranean. -

The 2016 SWFSC Billfish Newsletter

The SouthwestSWFSC Fisheries 2016 Billfish Science Newsletter Center’s 2016 Billfish Newsletter Global Tagging Map El Niño fishing conditions Catch-Photo-Release mobile phone application IGFA Great Marlin Race and satellite tagging 1 Top Anglers and Captains of 2015 SWFSC 2016 Billfish Newsletter Table of Contents Special Foreword …………………………………………………………….. 3 An Inside Look ……………………………………………………………..… 4 Prologue …………………………………………………………………….… 5 Introduction ……………………………………………………………..….… 5 The International Billfish Angler Survey ………………………………....... 7 Pacific blue marlin 9 Striped marlin 10 Indo-Pacific sailfish 11 Black marlin 13 Shortbill spearfish 13 Broadbill swordfish 14 The Billfish Tagging Program ……………………………………………..... 14 The Hawaiian Islands 16 2015 Tagging-at-a-Glance Map 17 Baja California and Guerrero, Mexico 18 Southern California 18 Western Pacific 18 Top Anglers and Captains Acknowledgements ……………………………. 19 Top Tagging Anglers 19 Top Tagging Captains 21 Tag Recoveries ……………………………………………………………….. 21 Science in Action: “The IGFA Great Marlin Race and Marlin Tagging” 23 Acknowledgements ………………………………………………………....... 25 Angler Photos ……………………………………………………………..….. 26 Congratulations to Captain Teddy Hoogs of the Bwana for winning this year’s cover photo contest! Teddy photographed this spectacular marlin off the coast of Hawaii. Fish on! 2 Special Forward James Wraith, director of the SWFSC Cooperative Billfish Tagging Program since 2007, recently left the SWFSC to move back to Australia. James was an integral part of the Highly Migratory Species (HMS) program. In addition to day-to-day work, James planned and organized the research cruises for HMS at the SWFSC and was involved in tagging thresher, blue, and mako sharks in the Southern California Bight for many years. We are sad to see him go but are excited for his future opportunities and thankful for his many contributions to the program over the last 10 years. -

Fao Species Catalogue

FAO Fisheries Synopsis No. 125, Volume 5 FIR/S125 Vol. 5 FAO SPECIES CATALOGUE VOL. 5. BILLFISHES OF THE WORLD AN ANNOTATED AND ILLUSTRATED CATALOGUE OF MARLINS, SAILFISHES, SPEARFISHES AND SWORDFISHES KNOWN TO DATE UNITED NATIONS DEVELOPMENT PROGRAMME FOOD AND AGRICULTURE ORGANIZATION OF THE UNITED NATIONS FAO Fisheries Synopsis No. 125, Volume 5 FIR/S125 Vol.5 FAO SPECIES CATALOGUE VOL. 5 BILLFISHES OF THE WORLD An Annotated and Illustrated Catalogue of Marlins, Sailfishes, Spearfishes and Swordfishes Known to date MarIins, prepared by Izumi Nakamura Fisheries Research Station Kyoto University Maizuru Kyoto 625, Japan Prepared with the support from the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) UNITED NATIONS DEVELOPMENT PROGRAMME FOOD AND AGRICULTURE ORGANIZATION OF THE UNITED NATIONS Rome 1985 The designations employed and the presentation of material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory. city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. M-42 ISBN 92-5-102232-1 All rights reserved . No part of this publicatlon may be reproduced. stored in a retriewal system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwase, wthout the prior permission of the copyright owner. Applications for such permission, with a statement of the purpose and extent of the reproduction should be addressed to the Director, Publications Division, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations Via delle Terme di Caracalla, 00100 Rome, Italy. -

Status of Billfish Resources and the Billfish Fisheries in the Western

SLC/FIAF/C1127 (En) FAO Fisheries and Aquaculture Circular ISSN 2070-6065 STATUS OF BILLFISH RESOURCES AND BILLFISH FISHERIES IN THE WESTERN CENTRAL ATLANTIC Source: ICCAT (2015) FAO Fisheries and Aquaculture Circular No. 1127 SLC/FIAF/C1127 (En) STATUS OF BILLFISH RESOURCES AND BILLFISH FISHERIES IN THE WESTERN CENTRAL ATLANTIC by Nelson Ehrhardt and Mark Fitchett School of Marine and Atmospheric Science, University of Miami Miami, United States of America FOOD AND AGRICULTURE ORGANIZATION OF THE UNITED NATIONS Bridgetown, Barbados, 2016 The designations employed and the presentation of material in this information product do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) concerning the legal or development status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The mention of specific companies or products of manufacturers, whether or not these have been patented, does not imply that these have been endorsed or recommended by FAO in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. The views expressed in this information product are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of FAO. ISBN 978-92-5-109436-5 © FAO, 2016 FAO encourages the use, reproduction and dissemination of material in this information product. Except where otherwise indicated, material may be copied, downloaded and printed for private study, research and teaching purposes, or for use in non-commercial products or services, provided that appropriate DFNQRZOHGJHPHQWRI)$2DVWKHVRXUFHDQGFRS\ULJKWKROGHULVJLYHQDQGWKDW)$2¶VHQGRUVHPHQWRI XVHUV¶YLHZVSURGXFWVRUVHUYLFHVLVQRWLPSOLHGLQDQ\ZD\ All requests for translation and adaptation rights, and for resale and other commercial use rights should be made via www.fao.org/contact-us/licence-request or addressed to [email protected]. -

Bermuda's Marine Reserve

POTENTIAL IMPACTS OF BERMUDA’s MARINE RESERVE ON SPORTFISHING TOURISM The Need to Explore Other Options ECONOMIC RETURNS CAN FLOW TO COASTAL NATIONS that Implement Billfish Conservation Measures Sportfishing eco-tourism is a strong economic driver for communities. Visting anglers are driven by the likelihood of catching a lot of billfish. Anticipated quality of a billfishing trip greatly influences anglers’ destination choices. Anglers most often select fishing destination where commercial fishing is restrained. Responsible management of billfish can maximize catch rates and economic returns to communities. As of 2011, more than 3.2 created Of the visitors who million anglers fished outside visited Panama that did not of the United States (exclud- fish, 30% said they would ing Canada) at least once in be interested in fishing on a the previous five years. Anglers subsequent trip to Panama. have many options when it comes to where they travel to fish, and countries must ISLA MUJERES, give particular attention to the socio-economic benefits MEXICO - Marlin and generated from sportfishing Sport Fishing magazines, both when making decisions that international publications could impact their sportfish- Photo courtesy of Viljoen with widespread circulation in ing industry. With only 0.3% the sportfishing community of these anglers reported to recognized Isla Mujeres, have taken their last fishing Mexico on the Yucatan trip to Bermuda, there is peninsula as being one of great potential for increasing the “most desired sailfishing tourism from sportfishing in destinations.” Marlin rated Bermuda.1 Isla as Number Three among its “Easy Billfish Destinations” to fish for Atlantic sailfish.Sport Fishing magazine rated Isla Mujeres in their “Top 20 Sailfish Hot Spots” of the world. -

Estimating Age and Growth of Little Tunny, Euthynnus Alletteratus, Off the Coast of Senegal, Using Dorsal Fin Spine Sections

SUMMARY PAPER Estimating Age and Growth of Little Tunny, Euthynnus alletteratus, off the Coast of Senegal, Using Dorsal Fin Spine Sections PATRICE M. CAYRE 1 and TAIB DIOUP ABSTRACT Estimates of age were made from counts of growtb bands on dorsal spine sections of 491 little tunny, Euthynnus alletteratus, captured off the coast of Senegal during 1979. Analysis of marginal growtb bands (by montb) indicates that these bands are probably formed during tbe cold season (November-May). Mean size at estimated age was deter mined for tbe first 8 yr of life. These results, tbougb not validated, closely approximated other studies for young fisb (estimated ages 1-3), but were bigbly variable for older age categories. Tbe index of average percent error (E) for age nates from our study was 10.5% and infers good precision. RESUME r La determination de I'age de 491 thonines, Euthynnus alletteratus, a ele Iaite par complage des anneaux de croissaneesurdeseoupes transversales du premier rayon de la nageoire dorsale. L'analyse mensuelle de la nature du bord externe des coupes, Indique que les annuli (i.e., zones translucides) se Iormeraient au cours de la saison froide (novembre a mail. Les tailles moyennes correspondant aux ages de I a 8 ans sonl donnees, Usresultats, bien que non valides par d'autres metbodes, sont Ires voisins de ceux exposes dans d'autres travaux pour les ages de I a 3 ans; des differences non negligeables apparaissent cependant pour res poissons plus ages. L'index de pourcentage moyen d'erreur (E) entre les ages attribues par les deux auteurs est de 10.50/0ce qui indique une bonne precision de la methode utilisee, INTRODUCTION age of little tunny collected off Senegal by counting growth bands on sections of dorsal spines, 2) determine the time of Commercial tuna fisheries in the eastern tropical Atlantic band formation by analysis of marginal growth bandspine sec seem to have reached their maximum sustainable yield for tions, and 3) estimate the degree of precision (repeatability) of most species (ICCAT 1977-82). -

Fisheries Series Part II: Commercial Policy & Management for Commercial Fishing

SAILFISHVERSION 14 TEENS TAKE ON BILLFISH CONSERVATION FISHERIES SERIES Part II: Commercial POLICY & MANAGEMENT for Commercial Fishing All About AQUACULTURE RECAPTURE MAPS Jr. Angler Profile SALES DE LA BARRE Cutler Bay Academy Welcomes The Billfish Foundation & Carey Chen CONTENTS Inside this issue of Sailfish FFEATURESEATURES 3 Fisheries Series Part II: Commercial Fishing 5 Aquaculture 7 Policy & Management of Commercial Fisheries 8 Commercial Fishing Review Questions 9 Cutler Bay Academy Students Enjoy Visit from TBF & Carey Chen 10 Billfish Advocacy at South Broward High ALSO INSIDE Get Involved: Track your school’s climate impact Recapture Maps Jr Angler Profile – Sales de La Barre We would like to extend our gratitude to the Fleming Family Foundation and the William H. and Mattie Wattis Harris Foundation for their belief in education as an important conservation tool. The Billfish Founation, educators, students, parents, the ocean and the fish are grateful for our sponsors generous donation that made this issue of Sailfish possible. Copyright 2014 • The Billfish Foundation • Editor: Peter Chaibongsai • Associate Editor: Elizabeth Black • Graphic Designer: Jackie Marsolais Sister Publications: Billfish and Spearfish magazines • Published by The Billfish Foundation • For subscription information contact: [email protected] by Jorie Heilman COMMERCIAL FISHING by Jorie Heilman What provides nutrition to 3 billion people gear advanced, humans could pursue food Top left: Aquacage snapper farm. Top right: Korean fishing boat. Below top to bottom: worldwide and is relied upon by 500 sources that were farther off the coast. Fishing boat in India. Commercial longline boat. Fishermen in the Seychelles. Commercial million people for their livelihoods? The Fish traps and nets were among the fishermen on a dock fixing a net. -

PROXIMATE and GENETIC ANALYSIS of BLACKFIN TUNA (T. Atlanticus)

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.11.03.366153; this version posted November 4, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. PROXIMATE AND GENETIC ANALYSIS OF BLACKFIN TUNA (T. atlanticus). Yuridia M. Núñez-Mata1, Jesse R. Ríos Rodríguez 1, Adriana L. Perales-Torres 1, Xochitl F. De la Rosa-Reyna2, Jesús A. Vázquez-Rodríguez 3, Nadia A. Fernández-Santos2, Humberto Martínez Montoya 1 * 1 Unidad Académica Multidisciplinaria Reynosa Aztlán – Universidad Autónoma de Tamaulipas. Reynosa, Tamaulipas. 2 Centro de Biotecnología Genómica – Instituto Politécnico Nacional. Reynosa, Tamaulipas. 3 Centro de Investigación en Salud Pública y Nutrición – Universidad Autónoma de Nuevo León. Monterrey, Nuevo León. *Correspondence: [email protected] ORCID: 0000-0003-3228-0054 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.11.03.366153; this version posted November 4, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. ABSTRACT The tuna meat is a nutritious food that possesses high content of protein, its low content of saturated fatty acids makes it a high demand food in the world. The Thunnus genus is composed of eight species, albacore (T. alalunga), bigeye (T. obesus), long tail tuna (T. tonggol), yellowfin tuna (T. albacares), pacific bluefin tuna (T. orientalis), bluefin tuna (T. maccoyii), Atlantic bluefin tuna ( T. thynnus) and blackfin tuna (T. atlanticus). The blackfin tuna (BFT) (Thunnus atlanticus) represent the smallest species within the Thunnus genus. -

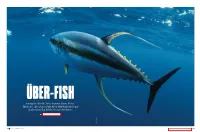

Among the World's Most Popular Game Fishes, Tunas Are Also

ÜBER-FISH Among the World’s Most Popular Game Fishes, Tunas Are Also Some of the Most Highly Evolved and Sophisticated of All the Ocean’s Predators BY DOUG OLANDER DANIEL GOEZ DANIEL 74 DECEMBER 2017 SPORTFISHINGMAG.COM 75 The Family Tree minimizes drag with a very low reduce the turbulence in the Tunas are part of the family drag coefficient,” optimizing effi- water ahead of the tail. Scombridae, which also includes cient swimming both at cruise Unlike most fishes with broad, mackerels, large and small. But and burst. While most fishes bend flexible tails that bend to scoop there are tunas, and then there their bodies side to side when water to move a fish forward, are, well, “true tunas.” moving forward, tunas’ bodies tunas derive tremendous That is, two groups don’t bend. They’re essentially thrust with thin, hard, lunate WHILE MOST FISHES BEND ( sometimes known as “tribes”) rigid, solid torpedoes. ( crescent-moon-shaped) tails dominate the tuna clan. One is And these torpedoes are that beat constantly, capable of THEIR BODIES SIDE TO SIDE Thunnini, which is the group perfectly streamlined, their 10 to 12 or more beats per second. considered true tunas, charac- larger fins fitting perfectly into That relentless thrust accounts WHEN MOVING FORWARD, terized by two separate dorsal grooves so no part of these fins for the unstoppable runs that fins and a relatively thick body. a number of highly specialized protrudes above the body surface. tuna make repeatedly when TUNAS’ BODIES DON’T BEND. The 15 species of Thunnini are features facilitate these They lack the convex eyes of hooked. -

Validity, Identification, and Distribution of the Roundscale Spearfish, <I>Tetrapturus Georgii</I> (Teleostei: Istio

BULLETIN OF MARINE SCIENCE, 79(3): 483–491, 2006 ValiDitY, IDentification, anD Distribution of THE RounDscale SPearfisH, TETRAPTURUS GEORGII (TELEOSTEI: ISTIOPHORIDAE): MorPHoloGical anD Molecular eviDence Mahmood S. Shivji, Jennifer E. Magnussen, Lawrence R. Beerkircher, George Hinteregger, Dennis W. Lee, Joseph E. Serafy, and Eric D. Prince ABSTRACT The roundscale spearfish, Tetrapturus georgii Lowe, 1840, is known only from four specimens from the Mediterranean and eastern North Atlantic. Additional specimens have not been identified since 1961, making the validity and distribution of this species unclear. Analysis of 16 billfish specimens from the western North Atlantic on the basis of scale morphology, anus position, and mitochondrial DNA confirms the validity of this species and extends its distribution. Mid-lateral scales are soft, notably rounded anteriorly, and bear 2–3 points distinct from those of the sympatric longbill spearfish Tetrapturus( pfluegeri Robins and de Sylva, 1963) and white marlin (Tetrapturus albidus Poey, 1860). Position of anus relative to first anal fin and a related morphometric ratio (distance from anus to first anal fin origin: height of first anal fin) are intermediate between T. pfluegeri and T. albidus. These characteristics match those described by Robins (1974) from the four eastern North Atlantic specimens of T. georgii. The mitochondrial ND4L, ND4, and cyt b gene sequences strongly support reciprocal monophyly of the western North Atlantic specimens relative to other Atlantic istiophorids. The difficulty in distinguishing between morphologically similar T. georgii and T. albidus in the field and the previ- ously unrecognized presence of T. georgii in the western North Atlantic has implica- tions for stock assessments of T. -

Validity, Identification, and Distribution of the Roundscale Spearfish

Nova Southeastern University NSUWorks Marine & Environmental Sciences Faculty Articles Department of Marine and Environmental Sciences NSUWorks Citation Mahmood S. Shivji, Jennifer E. Magnussen, Lawrence R. Beerkircher, George Hinteregger, Dennis W. Lee, Joseph E. Serafy, and Eric D. Prince. 2006. Validity, Identification, and Distribution of the Roundscale Spearfish, Tetrapturus georgii (Teleostei: Istiophoridae): Morphological and Molecular Evidence .Bulletin of Marine Science , (3) : 483 -491. https://nsuworks.nova.edu/occ_facarticles/374. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Marine and Environmental Sciences at NSUWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Marine & Environmental Sciences Faculty Articles by an authorized administrator of NSUWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 11-1-2006 Validity, Identification, and Distribution of the Roundscale Spearfish, Tetrapturus georgii (Teleostei: Istiophoridae): Morphological and Molecular Evidence Mahmood S. Shivji Nova Southeastern University, <<span class="elink">[email protected] Jennifer E. Magnussen Nova Southeastern University Lawrence R. Beerkircher National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration George Hinteregger National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Dennis W. Lee National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration See next page for additional authors Find out more information about Nova Southeastern University and the Halmos College of Natural Sciences and Oceanography. Follow this and additional works at: https://nsuworks.nova.edu/occ_facarticles Part of the Genetics and Genomics Commons, Marine Biology Commons, and the Oceanography and Atmospheric Sciences and Meteorology Commons This Article has supplementary content. View the full record on NSUWorks here: https://nsuworks.nova.edu/occ_facarticles/374 Authors Joseph E. Serafy National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, [email protected] Eric D. -

Spillover of the Atlantic Bluefin Tuna Offspring from Cages in the Adriatic Sea: a Multidisciplinary Approach and Assessment

RESEARCH ARTICLE Spillover of the Atlantic bluefin tuna offspring from cages in the Adriatic Sea: A multidisciplinary approach and assessment Tomislav DzÏoić1☯*, Gordana Beg Paklar1☯, Branka Grbec1☯, Stjepan Ivatek-SÏ ahdan2☯, Barbara Zorica3☯, Tanja SÏ egvić-Bubić4☯, Vanja ČikesÏ Keč3☯, Ivana Lepen Pleić4☯, Ivona Mladineo4☯, Leon GrubisÏić4☯, Philippe Verley5☯ 1 Physical Oceanography Laboratory, Institute of Oceanography and Fisheries, Split, Croatia, 2 Research and Development Division, Meteorological and Hydrological Service, Zagreb, Croatia, 3 Laboratory of a1111111111 Fisheries Science and Management of Pelagic and Demersal Resources, Institute of Oceanography and a1111111111 Fisheries, Split, Croatia, 4 Laboratory for Aquaculture, Institute of Oceanography and Fisheries, Split, a1111111111 Croatia, 5 Institute de recherche pour le developpement, UMR Botany and Modelling of Plant Architecture a1111111111 and Vegetation, Montpellier, France a1111111111 ☯ These authors contributed equally to this work. * [email protected] OPEN ACCESS Abstract Citation: DzÏoić T, Beg Paklar G, Grbec B, Ivatek- During routine monitoring of commercial purse seine catches in 2011, 87 fingerling speci- SÏahdan S, Zorica B, SÏegvić-Bubić T, et al. (2017) Spillover of the Atlantic bluefin tuna offspring from mens of scombrids were collected in the southern Adriatic Sea. Sequencing of the mito- cages in the Adriatic Sea: A multidisciplinary chondrial DNA control region locus inferred that specimens belonged to the Atlantic bluefin approach and assessment. PLoS ONE 12(11): tuna, Thunnus thynnus (Linnaeus, 1758) (N = 29), bullet tuna, Auxis rochei (Risso, 1810) e0188956. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal. pone.0188956 (N = 30) and little tunny, Euthynnus alletteratus, Rafinesque, 1810 (N = 28). According to previously published growth parameters, the age of the collected specimens was estimated Editor: Aldo Corriero, Universita degli Studi di Bari Aldo Moro, ITALY at approximately 30±40 days, suggesting they might have been spawned in the Adriatic Sea, contrary to the current knowledge.