Downloaded from Manchesterhive.Com at 09/26/2021 06:43:35PM Via Free Access

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Report and Accounts 2004/2005

THE BFI PRESENTSANNUAL REPORT AND ACCOUNTS 2004/2005 WWW.BFI.ORG.UK The bfi annual report 2004-2005 2 The British Film Institute at a glance 4 Director’s foreword 9 The bfi’s cultural commitment 13 Governors’ report 13 – 20 Reaching out (13) What you saw (13) Big screen, little screen (14) bfi online (14) Working with our partners (15) Where you saw it (16) Big, bigger, biggest (16) Accessibility (18) Festivals (19) Looking forward: Aims for 2005–2006 Reaching out 22 – 25 Looking after the past to enrich the future (24) Consciousness raising (25) Looking forward: Aims for 2005–2006 Film and TV heritage 26 – 27 Archive Spectacular The Mitchell & Kenyon Collection 28 – 31 Lifelong learning (30) Best practice (30) bfi National Library (30) Sight & Sound (31) bfi Publishing (31) Looking forward: Aims for 2005–2006 Lifelong learning 32 – 35 About the bfi (33) Summary of legal objectives (33) Partnerships and collaborations 36 – 42 How the bfi is governed (37) Governors (37/38) Methods of appointment (39) Organisational structure (40) Statement of Governors’ responsibilities (41) bfi Executive (42) Risk management statement 43 – 54 Financial review (44) Statement of financial activities (45) Consolidated and charity balance sheets (46) Consolidated cash flow statement (47) Reference details (52) Independent auditors’ report 55 – 74 Appendices The bfi annual report 2004-2005 The bfi annual report 2004-2005 The British Film Institute at a glance What we do How we did: The British Film .4 million Up 46% People saw a film distributed Visits to -

Home Sweet Home

FINAL-1 Sat, Jun 30, 2018 5:22:48 PM tvupdateYour Weekly Guide to TV Entertainment For the week of July 8 - 14, 2018 Home sweet home Patricia Clarkson stars in “Sharp Objects” INSIDE •Sports highlights Page 2 •TV Word Search Page 2 •Family Favorites Page 4 •Hollywood Q&A Page14 When a big city crime reporter (Amy Adams, “Arrival,” 2016) returns to her hometown to cover a string of gruesome killings, not all is what it seems. Jean-Marc Vallée (“Dallas Buyers Club,” 2013) reunites with HBO to helm another beloved novel adaptation in Gillian Flynn’s “Sharp Objects,” premiering Sunday, July 8, on HBO. The ensemble cast also includes Patricia Clarkson (“House of Cards”) and Chris Messina (“The Mindy Project”). WANTED WANTED MOTORCYCLES, SNOWMOBILES, OR ATVS GOLD/DIAMONDS BUY SELL ✦ 37 years in business; A+ rating with the BBB. TRADE Salem, NH • Derry, NH • Hampstead, NH • Hooksett, NH ✦ For the record, there is only one authentic CASH FOR GOLD, Bay 4 Newburyport, MA • North Andover, MA • Lowell, MA Group Page Shell PARTS & ACCESSORIES IT’S MOLD ALLERGY SEASON We Need: SALESMotorsports & SERVICE DON’T LET IT GET YOU DOWN 5 x 3” Gold • Silver • Coins • Diamonds MASS. MOTORCYCLE 1 x 3” Are you suffering from itchy eyes, sneezing, sinusitis or INSPECTIONS asthma? Alleviate your mold allergies this season. We are the ORIGINAL and only AUTHENTIC Call or schedule your appointment online with New England Allergy today. CASH FOR GOLD Appointments Available Now on the Methuen line, above Enterprise Rent-A-Car 978-683-4299 at 527 So. Broadway, Rte. -

Catalogo Novedades Dvd Abril 2013

CINE INTERNACIONAL AGUA PARA ALTA SOCIEDAD ELEFANTES DIR.: Francis Lawrence DIR.: Charles Walters INT.: Reese Witherspoon, INT.: Bing Crosby, Grace Robert Pattinson, Christoph Kelly, Frank Sinatra Waltz AÑO: 1956 AÑO: 2011 PREMIOS: 2 nominaciones PREMIOS: al Óscar. AMANECER (parte 1) ARGO DIR.: Bill Condon DIR.: Ben Affleck INT.: Kristen Stewart, Robert INT.: Ben Affleck, Bryan Pattinson, Taylor Lautner Cranston, Alan Arkin AÑO: 2011 AÑO: 2012 PREMIOS: PREMIOS: 3 Óscar, 2 Globos de Oro, 3 Premios BAFTA, 1 Premio César, 2 Critics Choice Awards. CINE INTERNACIONAL 1 THE ARTIST BREVE ENCUENTRO DIR.: Michel Hazanavicius DIR.: David Lean INT.: Jean Dujardin, INT.: Celia Johnson, Trevor Bérénica Bejo, James Howard, Stanley Holloway Cromwell AÑO: 1945 AÑO: 2011 PREMIOS: 3 nominaciones PREMIOS: 5 Óscar, 3 al Óscar, Gran Premio del Globos de Oro, 7 premios Festival de Cannes, mejor BAFTA, 6 premios César, actriz del Círculo de Críticos mejor actor Festival de de Nueva York. Cannes. CACHÉ (ESCONDIDO) LA CALUMNIA DIR.: Michael Haneke DIR.: William Wyler INT.: Daniel Auteil, Juliete INT.: Audrey Hepburn, Binoche, Maurice Bénichou Shirley MacLaine, James Garner AÑO: 2005 AÑO: 1961 PREMIOS: 3 premios del Festival de Cannes, 5 PREMIOS: 5 nominaciones premios Academia de Cine al Óscar. Europeo CINE INTERNACIONAL 2 EL CARDENAL LA CINTA BLANCA DIR.: Otto Preminger DIR.: Michael Haneke INT.: Tom Tryon, John INT.: Susanne Lothar, Ulrich Huston, Romy Schneider Tukur, Burghart Klaussner AÑO: 1963 AÑO: 2009 PREMIOS: 6 nominaciones PREMIOS: Palma de Oro de al Óscar y 3 Globos de Oro. Festival de Cannes, Globo de Oro mejor película de habla no inglesa, premio FIPRESCI, 3 premios del cine europeo. -

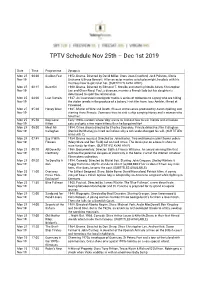

TPTV Schedule Nov 25Th – Dec 1St 2019

TPTV Schedule Nov 25th – Dec 1st 2019 Date Time Programme Synopsis Mon 25 00:00 Sudden Fear 1952. Drama. Directed by David Miller. Stars Joan Crawford, Jack Palance, Gloria Nov 19 Grahame & Bruce Bennett. After an actor marries a rich playwright, he plots with his mistress how to get rid of her. (SUBTITLES AVAILABLE) Mon 25 02:15 Beat Girl 1960. Drama. Directed by Edmond T. Greville and starring Noelle Adam, Christopher Nov 19 Lee and Oliver Reed. Paul, a divorcee, marries a French lady but his daughter is determined to spoil the relationship. Mon 25 04:00 Last Curtain 1937. An insurance investigator tracks a series of robberies to a gang who are hiding Nov 19 the stolen jewels in the produce of a bakery. First film from Joss Ambler, filmed at Pinewood. Mon 25 05:20 Honey West 1965. Matter of Wife and Death. Classic crime series produced by Aaron Spelling and Nov 19 starring Anne Francis. Someone tries to sink a ship carrying Honey and a woman who hired her. Mon 25 05:50 Dog Gone Early 1940s cartoon where 'dog' wants to find out how to win friends and influence Nov 19 Kitten cats and gets a few more kittens than he bargained for! Mon 25 06:00 Meet Mr 1954. Crime drama directed by Charles Saunders. Private detective Slim Callaghan Nov 19 Callaghan (Derrick De Marney) is hired to find out why a rich uncle changed his will. (SUBTITLES AVAILABLE) Mon 25 07:45 Say It With 1934. Drama musical. Directed by John Baxter. Two well-loved market flower sellers Nov 19 Flowers (Mary Clare and Ben Field) fall on hard times. -

Guillaume Durand : Canal Plus D'info

LeMonde Job: WMR2397--0002-0 WAS TMR2397-2 Op.: XX Rev.: 06-06-97 T.: 19:13 S.: 75,06-Cmp.:07,08, Base : LMQPAG 31Fap:99 No:0046 Lcp: 196 CMYK ENTRETIEN Guillaume Durand : Canal Plus d’info Porté au pinacle puis « jeté aux loups », ressourcé par trois années passées à LCI, le futur remplaçant de Philippe Gildas à « Nulle Part Ailleurs » parle de sa conception de l’information, de TF 1, du service public et de la télévision en général quarante-cinq ans, sibles, confronté à des exigences Guillaume Durand d’audience qu’il devait résoudre, comme touche, dit-il, à la ça, du jour au lendemain. C’était dingue. sérénité. Après On critique souvent Mougeotte pour sa Europe 1 de Jean- dureté. Mais quiconque est nommé patron Luc Lagardère et de TF 1 se transforme inévitablement en ce feue La Cinq du duo Mougeotte-là, du jour au lendemain, ou Hersant-Berlusconi, alors il laisse sa place. Moi, je connais les après TF 1 et LCI de deux Mougeotte, celui qui est caricaturé Francis Bouygues, le voilà qui arrive par les Guignols, mais l’autre aussi, celui aujourd’huiA à Canal Plus pour remplacer qui fut mon premier « patron de presse » à Philippe Gildas à la tête de l’équipe de Europe 1, qui a plein de qualités humaines « Nulle part ailleurs », la vitrine (en clair) et que j’aime beaucoup. C’est moins le de la chaîne cryptée. Première apparition à procès de l’homme qu’il faut faire que la rentrée. celui du monde contemporain, tel que Journaliste-vedette des années-pail- Viviane Forrester le dénonce dans son livre lettes, porté aux nues puis « jeté aux SCHWARTZ/CANAL+ P. -

Coventry & Warwickshire Cover

Coventry & Warwickshire Cover April 2018 .qxp_Coventry & Warwickshire Cover 23/03/2018 16:36 Page 1 THE GAME OF LOVE & CHAI Your FREE essential entertainment guide for the Midlands AT THE BELGRADE COVENTRY & WARWICKSHIRE WHAT’S ON APRIL 2018 2018 ON APRIL WHAT’S WARWICKSHIRE & COVENTRY Coventry & Warwickshire ISSUE 388 APRIL 2018 ’ WhatFILM I COMEDY I THEATRE I GIGS I VISUAL ARTS I EVENTSs I FOOD On warwickshirewhatson.co.uk inside: PART OF WHAT’S ON MEDIA GROUP GROUP MEDIA ON WHAT’S OF PART Yourthe 16-pagelist week by week listings guide CABBAGE Neo-post-punk Manchester five-piece visit The Empire TWITTER: @WHATSONWARWICKS TWITTER: @WHATSONWARWICKS PROTEIN DANCE award-winning company at Warwick Arts Centre FACEBOOK: @WHATSONWARWICKSHIRE KIDTROPOLIS a youngster’s paradise at the NEC WARWICKSHIREWHATSON.CO.UK (IFC) Warwickshire.qxp_Layout 1 23/03/2018 15:09 Page 1 Contents April Warwicks_Worcs.qxp_Layout 1 22/03/2018 14:33 Page 2 April 2018 Contents Bollywood farce - Nigel Planer’s The Game Of Love & Chai opens at the Belgrade - feature page 8 Martine McCutcheon Wicked Romeo And Juliet the list the Love Actually star Lost hit musical returns to cast its brand new RSC staging of the your 16-page And Found at The Core spell over Midlands audiences world’s most famous love story week-by-week listings guide page 17 feature page 22 page 24 page 51 inside: 4. First Word 11. Food 17. Music 20. Comedy 24. Theatre 35. Film 40. Visual Arts 43. Events fb.com/whatsonwarwickshire fb.com/whatsonworcestershire @whatsonwarwicks @whatsonworcs Warwickshire -

Film Visti Nel 2014 (In Ordine Alfabetico)

film visti nel 2014 (in ordine alfabetico) quelli con sfondo giallo mi sono piaciuti in particolar modo 21 Days Basil Dean 1940 Vivien Leigh, Leslie Banks, Laurence Olivier 3 Idiots Rajkumar Hirani 2009 Aamir Khan, Madhavan, Mona Singh, Kareena Kapoor 55 days in peking Nicholas Ray 1963 Charlton Heston, Ava Gardner, David Niven 9 songs Michael Winterbottom 2004 Kieran O'Brien, Margo Stilley, Huw Bunford | A Bronx Tale Robert De Niro 1993 Robert De Niro, Chazz Palminteri A Life at Stake Paul Guilfoyle 1954 Angela Lansbury, Keith Andes, Douglass Dumbrille A Serious Man Joel Coen 2009 Michael Stuhlbarg, Richard Kind, Sari Lennick A Tale Of Two Cities Ralph Thomas 1958 Dirk Bogarde, Dorothy Tutin, Cecil Parker A.T.M.: ¡¡A toda máquina!! Ismael Rodríguez 1951 Pedro Infante, Luis Aguilar, Aurora Segura After hours Martin Scorsese 1985 Griffin Dunne, Rosanna Arquette Alma gitana Chus Gutiérrez 1996 Amara Carmona, Pedro Alonso, Peret Amores Perros Aleja. Gonzalez Inarritu 1999 E. Echevarría, G. García Bernal, G. Toledo Ana y Los Lobos Carlos Saura 1973 G. Chaplin, F. Fernán Gómez, J. M. Prada And Then There Were None René Claire 1945 Barry Fitzgerald, Walter Huston, Louis Hayward Andalucía chica José Ulloa 1988 Antonio Molina, Mara Vador, Raquel Evans Another Man's Poison Irving Rapper 1951 Bette Davis, Gary Merrill, Emlyn Williams Asphalt Joe May 1929 Albert Steinrück, Else Heller, Gustav Fröhlich Aventurera Alberto Gout 1950 Ninón Sevilla, Tito Junco, Andrea Palma Awaara Raj Kapoor 1951 Prithviraj Kapoor, Nargis, Raj Kapoor, K.N. Singh Bajo -

Above Suspicion: the Red Dahlia

1 ABOVE SUSPICION: THE RED DAHLIA Above Suspicion: The Red Dahlia DC Anna Travis (Kelly Reilly) is back, reunited with the inimitable DCI James Langton (Ciarán Hinds), to face her most challenging and terrifying case yet. When the body of a young woman is discovered by the Thames, sadistically mutilated and drained of blood, it would seem an ominous re-enactment of the infamously unsolved murder, from 1940s Los Angeles, dubbed The Black Dahlia. The three part drama, Above Suspicion: The Red Dahlia, is adapted by Lynda La Plante from her successful second novel about rookie detective, Anna Travis. It is produced by La Plante Productions for ITV1. Kelly Reilly (He Kills Coppers, Joe’s Palace, Eden Lake, Mrs Henderson Presents) returns to the role of Anna Travis. Acclaimed actor Ciarán Hinds (There Will Be Blood, Margot at the Wedding, The Mayor of Casterbridge, Prime Suspect) stars as her boss, the volatile Detective Chief Inspector James Langton. They are joined by Shaun Dingwall as Detective Inspector Mike Lewis, Celyn Jones (First, Joe’s Palace, Grange Hill) as Detective Sergeant Paul Barolli, Michelle Holmes (Red Riding: 1980, The Chase, Merseybeat) as Detective Constable Barbara Maddox and Amanda Lawrence (Little Dorrit, Clone) as Detective Constable Joan Faukland. Guest stars in the new series include Simon Williams (Spooks, Sense and Sensibility), Sylvia Syms (Collision, The Queen), Holliday Grainger (Merlin, Demons), Edward Bennett (After You’re Gone, Silent Witness) and Hannah Murray (In Bruges, Skins) Director of Drama Laura Mackie says: “Above Suspicion was one of the highlights of the Winter Season on ITV1 and I’m delighted that Lynda is bringing Anna Travis back for another gripping investigation”. -

New 2020 Drama CV

1 DARCIA MARTIN DIRECTOR Curriculum Vitae My film-making career began in factual and documentaries before directing drama. I collaborated with the writer and producer of my last short film to create a female film-making collective. Recently secured representation in the U.S and also have a U.K agent. Film & Television • Father Brown - BBC 1 Drama series based on novels of GK Chesterton. Starring Mark Williams. 2 episodes • Shakespeare and Hathaway – BBC1 Comedy/Drama detective show produced by Ella Kelly. I directed two episodes including series 2 finale • First – short film – Director. Short film written by Emma Ko, produced by Jane Steventon. Premiered at British Horror Film Festival, Leicester Square • All the Wild Horses – Producer. International Cinematic release 2018/19. Won Best International Feature Documentary at Galway film festival. Won awards at various international festivals • Call The Midwife – Series 5 Finale -Episodes 7 & 8 (written by Heidi Thomas. Produced by Pippa Harris. Winner of National TV Award). 10 million viewers watched my series finale on BBC1 • Call The Midwife – Series 4 Finale – Episodes 7 & 8 (written by Harriet Warner and Heidi Thomas. Produced by Pippa Harris. Winner of TV Choice Award) • Hollyoaks -LATE NIGHT SPECIAL- Ep3. 60’ Youth Drama. Shot on location. Produced by Jane Steventon. Starring Emmet J Scanlon • Hollyoaks – award winning Channel 4 youth drama produced by Bryan Kirkwood • Underage + Pregnant – Drama Pilot for BBC Campaigns • A grand don’t come for free - BBC Drama Pilot • Judge John Deed : 2 hour special, series finale – Evidence of Harm BBC1 • Judge John Deed – Silent Killer BBC1 Drama 90’ Episode 4. -

TPTV Schedule May 4Th to May 10Th 2020

TPTV Schedule May 4th to May 10th 2020 Date Time Programme Synopsis Mon 04 01:50 Psyche 59 1964. Drama. Directed by Alexandre Singer. Stars Patricia Neal, Curt Jurgens & May 20 Samantha Eggar. The blind wife of an industrialist begins to learn that her malady may not be the result of an injury. Mon 04 03:50 I Lived With 1933. Drama. A penniless Russian Prince (Ivor Novello) is befriended by Ada (Ida May 20 You Lupino) who takes him home to live with her folks. Co-written by Ivor Novello. (SUBTITLES AVAILABLE) Mon 04 05:45 Hello Pirro 'Hello Pirro', the first episode made in 1949 of what became a hugely popular May 20 puppet. Pat Patterson introduces Pirro to mirrors! Mon 04 06:00 Windom's 1957. Drama. Directed by Ronald Neame. Stars Peter Finch, Mary Ure, Natasha May 20 Way Parry, Robert Flemyng & Michael Hordern. A doctor's wife joins him at his remote practice to try and patch up their marriage Mon 04 08:10 Crossroads 1960. Crime. Director: Gerry Anderson. Stars Anthony Oliver, Arthur Rigby. A PC May 20 to Crime suspects that a gang of lorry hijackers, operating from a transport cafe, is behind a series of vehicle thefts. (SUBTITLES AVAILABLE) Mon 04 09:20 Man of Aran 1934. Doc. Director: Robert Flatherty. A portrayal of life off the western coast of May 20 Ireland where families eked out a living from potatoes and hunting basking shark. Mon 04 11:00 The Bad Eye Rose Rosetti. Captain Matt Holbrook (Robert Taylor) leads a squad of May 20 Detectives brave and tough detectives tackling crime. -

Film Noir Database

www.kingofthepeds.com © P.S. Marshall (2021) Film Noir Database This database has been created by author, P.S. Marshall, who has watched every single one of the movies below. The latest update of the database will be available on my website: www.kingofthepeds.com The following abbreviations are added after the titles and year of some movies: AFN – Alternative/Associated to/Noirish Film Noir BFN – British Film Noir COL – Film Noir in colour FFN – French Film Noir NN – Neo Noir PFN – Polish Film Noir www.kingofthepeds.com © P.S. Marshall (2021) TITLE DIRECTOR Actor 1 Actor 2 Actor 3 Actor 4 13 East Street (1952) AFN ROBERT S. BAKER Patrick Holt, Sandra Dorne Sonia Holm Robert Ayres 13 Rue Madeleine (1947) HENRY HATHAWAY James Cagney Annabella Richard Conte Frank Latimore 36 Hours (1953) BFN MONTGOMERY TULLY Dan Duryea Elsie Albiin Gudrun Ure Eric Pohlmann 5 Against the House (1955) PHIL KARLSON Guy Madison Kim Novak Brian Keith Alvy Moore 5 Steps to Danger (1957) HENRY S. KESLER Ruth Ronan Sterling Hayden Werner Kemperer Richard Gaines 711 Ocean Drive (1950) JOSEPH M. NEWMAN Edmond O'Brien Joanne Dru Otto Kruger Barry Kelley 99 River Street (1953) PHIL KARLSON John Payne Evelyn Keyes Brad Dexter Frank Faylen A Blueprint for Murder (1953) ANDREW L. STONE Joseph Cotten Jean Peters Gary Merrill Catherine McLeod A Bullet for Joey (1955) LEWIS ALLEN Edward G. Robinson George Raft Audrey Totter George Dolenz A Bullet is Waiting (1954) COL JOHN FARROW Rory Calhoun Jean Simmons Stephen McNally Brian Aherne A Cry in the Night (1956) FRANK TUTTLE Edmond O'Brien Brian Donlevy Natalie Wood Raymond Burr A Dangerous Profession (1949) TED TETZLAFF George Raft Ella Raines Pat O'Brien Bill Williams A Double Life (1947) GEORGE CUKOR Ronald Colman Edmond O'Brien Signe Hasso Shelley Winters A Kiss Before Dying (1956) COL GERD OSWALD Robert Wagner Jeffrey Hunter Virginia Leith Joanne Woodward A Lady Without Passport (1950) JOSEPH H. -

Jun & Jul Guide

VISIT home box office HOME mcr. 0161 200 1500 2 Tony Wilson Place DON’T MISS... Manchester org THEATRE ART YOUNG M15 4FN home EXHIBITION/ LA MOVIDA INFORMATION & HOME presents Until Mon 17 Jul PEOPLE ROSE Free, drop in BOOKING Until Sat 10 Jun YOUNG IDENTITY homemcr.org/la-movida HOMEmcr.org Tickets £26.50 - £10 Every Monday, 19:00 0161 200 1500 homemcr.org/rose (excluding Bank Holidays) EXHIBITION TOUR: LA MOVIDA Free, drop in [email protected] Accessible Performances Thu 1 Jun, 18:30 homemcr.org/young-identity BSL Interpreted Free, booking required Tue 6 Jun, 19:30 homemcr.org/la-movida ACCESSIBILITY HOMEmcr.org/accessibility Caption Subtitled HOME PROJECTS: EDEN KÖTTING REGULAR Wed 7 Jun, 19:30 & ANONYMOUS BOSCH TOUCH Audio Described Touch Wed 21 Jun – Sun 30 Jul EVENTS KEEP IN TOUCH TOUR Tour Granada Foundation Galleries 1 & 2 PLAYREADING Twitter @HOME_mcr Thu 8 Jun, 18:30 Free, drop in Fri 2 Jun, 11:00 Facebook HOMEmcr homemcr.org/home-projects Audio Described Fri 7 Jul, 11:00 Instagram HOMEmcr Thu 8 Jun, 19:30 Tickets £5 (scripts and CEREMONY Audioboom HOMEmcr refreshments included) Event/ Playreading: The Shroud PART OF MIF17 homemcr.org/playreading Youtube HOMEmcrorg Maker + Q&A with Palestinian Sun 16 Jul, 18:00 writer Ahmed Masoud Free, booking required JMK RESIDENCY Fri 9 Jun, 19:00 homemcr.org/ceremony OPENING TIMES Wed 7 – Fri 9 Jun, 10:00 – 17:00 Tickets £3 Box Office homemcr.org/shroud-maker Free, application required homemcr.org/jmk-jun Mon – Sun: 12:00 – 20:00 creatives Main Gallery Blast Theory and Hydrocracker MOTHERS