General Assembly Distr

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Building Viable Community Peace Alliances for Land Restitution in Burundi

BUILDING VIABLE COMMUNITY PEACE ALLIANCES FOR LAND RESTITUTION IN BURUNDI Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Public Administration – Peace Studies Theodore Mbazumutima Professor Geoff Harris BComm DipEd MEc PhD Supervisor ............................................ Date.............................. Dr. Sylvia Kaye BS MS PhD Co-supervisor ...................................... Date............................. May 2018 i DECLARATION I Theodore Mbazumutima declare that a. The research reported in this thesis is my original research. b. This thesis has not been submitted for any degree or examination at any other university. c. All data, pictures, graphs or other information sourced from other sources have been acknowledged accordingly – both in-text and in the References sections. d. In the cases where other written sources have been quoted, then: 1. The quoted words have been re-written but the general information attributed to them has been referenced: 2. Where their exact words have been used, their writing has been placed inside quotation marks and duly referenced. ……………………………. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS It is absolutely not possible to name each and every person who inspired and helped me to carry out this research. However, I would like to single out some of them. I sincerely thank Professor Geoff Harris for supervising me and tirelessly providing comments and guidelines throughout the last three years or so. I also want to thank the DUT University for giving me a place and a generous scholarship to enable me to study with them. All the staff at the university and especially the librarian made me feel valued and at home. I would like to register my sincere gratitude towards Rema Ministries (now Rema Burundi) administration and staff for giving me time off and supporting me to achieve my dream. -

Integrated Regional Information Network (IRIN): Burundi

U.N. Department of Humanitarian Affairs Integrated Regional Information Network (IRIN) Burundi Sommaire / Contents BURUNDI HUMANITARIAN SITUATION REPORT No. 4...............................................................5 Burundi: IRIN Daily Summary of Main Events 26 July 1996 (96.7.26)..................................................9 Burundi-Canada: Canada Supports Arusha Declaration 96.8.8..............................................................11 Burundi: IRIN Daily Summary of Main Events 14 August 1996 96.8.14..............................................13 Burundi: IRIN Daily Summary of Main Events 15 August 1996 96.8.15..............................................15 Burundi: Statement by the US Catholic Conference and CRS 96.8.14...................................................17 Burundi: Regional Foreign Ministers Meeting Press Release 96.8.16....................................................19 Burundi: IRIN Daily Summary of Main Events 16 August 1996 96.8.16..............................................21 Burundi: IRIN Daily Summary of Main Events 20 August 1996 96.8.20..............................................23 Burundi: IRIN Daily Summary of Main Events 21 August 1996 96.08.21.............................................25 Burundi: Notes from Burundi Policy Forum meeting 96.8.23..............................................................27 Burundi: IRIN Summary of Main Events for 23 August 1996 96.08.23................................................30 Burundi: Amnesty International News Service 96.8.23.......................................................................32 -

Refugies Et Deplaces Au Burundi: Desamorcer La Bombe Fonciere

REFUGIES ET DEPLACES AU BURUNDI: DESAMORCER LA BOMBE FONCIERE 7 octobre 2003 ICG Rapport Afrique N°70 Nairobi/Bruxelles TABLE DES MATIERES SYNTHESE ET RECOMMENDATIONS ...................................................................................i I. INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................... 1 II. ORIGINES POLITIQUES ET JURIDIQUE DE LA BOMBE FONCIERE BURUNDAISE................................................................................................................ 3 A. UN REGIME POST-COLONIAL D’ENCADREMENT ET D’EXPLOITATION DE LA PAYSANNERIE ...3 1. Le cas des biens des réfugiés de 1972 .......................................................................3 2. Les cas de sociétés para-étatiques de développement rural et la dilapidation des terres domaniales .......................................................................................................5 B. L’INFLATION DES SPOLIATIONS DEPUIS LE DEBUT DE LA GUERRE.........................................6 C. LE CODE FONCIER DE 1986, OUTIL IDEAL POUR LA LEGALISATION DES SPOLIATIONS .....7 III. LES CONDITIONS D’UNE APPLICATION REUSSIE DE L’ACCORD D’ARUSHA ..................................................................................................................... 9 A. LES PROPOSITIONS DE L’ACCORD D’ARUSHA .....................................................................9 B. LA CREATION D’UN SYSTEME JUDICIAIRE TRANSITIONNEL SPECIFIQUE POUR LES QUESTIONS FONCIERES ..........................................................................................................................10 -

EN Web Final

The Burundi Human Rights Initiative A FAÇADE OF PEACE IN A LAND OF FEAR Behind Burundi’s human rights crisis January 2020 A Façade of Peace in a Land of Fear WHAT IS THE BURUNDI HUMAN RIGHTS INITIATIVE? The Burundi Human Rights Initiative (BHRI) is an independent human rights project that aims to document the evolving human rights situation in Burundi, with a particular focus on events linked to the 2020 elections. It intends to expose the drivers of human rights violations with a view to establishing an accurate record that will help bring justice to Burundians and find a solution to the ongoing human rights crisis. BHRI’s publications will also analyse the political and social context in which these violations occur to provide a deeper and more nuanced understanding of human rights trends in Burundi. BHRI has no political affiliation. Its investigations cover human rights violations by the Burundian government as well as abuses by armed opposition groups. Carina Tertsakian and Lane Hartill lead BHRI and are its principal researchers. They have worked on human rights issues in Burundi and the Great Lakes region of Africa for many years. BHRI’s reports are the products of their collaboration with a wide range of people inside and outside Burundi. BHRI welcomes feedback on its publications as well as further information about the human rights situation in Burundi. Please write to [email protected] or +1 267 896 3399 (WhatsApp). Additional information is available at www.burundihri.org. ©2020 The Burundi Human Rights Initiative Cover photo: President Pierre Nkurunziza, 2017 ©2020 Private 2 The Burundi Human Rights Initiative TABLE OF CONTENTS Methodology 5 Acronyms 6 Summary 7 Recommendations 9 To the Burundian government and the CNDD-FDD 9 To the CNL 9 To foreign governments and other international actors 10 Map of Burundi 12 1. -

BURUNDI on G O O G GITARAMA N Lac Vers KIBUYE O U Vers KAYONZA R R a KANAZI Mugesera a Y B N a a BIRAMBO Y K KIBUNGO N A

29°30' vers RUHENGERI v. KIGALI 30° vers KIGALI vers RWAMAGANA 30°30' Nyabar BURUNDI on go o g GITARAMA n Lac vers KIBUYE o u vers KAYONZA r r a KANAZI Mugesera a y b n a a BIRAMBO y k KIBUNGO N A M RUHANGO w A D o N g A Lac o Lac BURUNDI W Sake KIREHE Cohoha- R Nord vers KIBUYE KADUHA Chutes de A a k r vers BUGENE NYABISINDU a ge Rusumo Gasenyi 1323 g a Nzove er k K a A 1539 Lac Lac ag era ra Kigina Cohoha-Sud Rweru Rukara KARABA Bugabira GIKONGORO Marembo Giteranyi vers CYANGUGU 1354 Runyonza Kabanga 1775 NGARA 2°30' u Busoni Buhoro r a Lac vers NYAKAHURA y n aux Oiseaux bu a Murore Bwambarangwe u BUGUMYA K v Kanyinya Ru Ntega hwa BUTARE Ru A GISAGARA Kirundo Ruhorora k Gitobe a Kobero n e vers BUVAKU Ruziba y Mutumba ny 2659 Mont a iza r C P u BUSORO 1886 Gasura A Twinyoni 1868 Buhoro R Mabayi C MUNINI Vumbi vers NYAKAHURA Murehe Rugari T A N Z A N I E 923 Butihinda Mugina Butahana aru Marangara Gikomero RULENGE y Gashoho n 1994 REMERA a u k r 1818 Rukana a Birambi A y Gisanze 1342 Ru Rusenda n s Rugombo Buvumo a Nyamurenza iz Kiremba Muyange- i N Kabarore K AT Busiga Mwumba Muyinga IO Gashoho vers BUVAKU Cibitoke N Bukinanyana A 2661 Jene a L ag Gasorwe LUVUNGI Gakere w Ngozi us Murwi a Rwegura m ntw Gasezerwa ya ra N bu R Gashikanwa 1855 a Masango u Kayanza o vu Muruta sy MURUSAGAMBA K Buhayira b Gahombo Tangara bu D u ya Muramba Buganda E Mubuga Butanganika N 3° 2022 Ntamba 3° L Gatara Gitaramuka Ndava A Buhinyuza Ruhororo 1614 Muhanga Matongo Buhiga Musigati K U Bubanza Rutsindu I Musema Burasira u B B b MUSENYI I Karuzi u U Kigamba -

BURUNDI: Carte De Référence

BURUNDI: Carte de référence 29°0'0"E 29°30'0"E 30°0'0"E 30°30'0"E 2°0'0"S 2°0'0"S L a c K i v u RWANDA Lac Rweru Ngomo Kijumbura Lac Cohoha Masaka Cagakori Kiri Kiyonza Ruzo Nzove Murama Gaturanda Gatete Kayove Rubuga Kigina Tura Sigu Vumasi Rusenyi Kinanira Rwibikara Nyabisindu Gatare Gakoni Bugabira Kabira Nyakarama Nyamabuye Bugoma Kivo Kumana Buhangara Nyabikenke Marembo Murambi Ceru Nyagisozi Karambo Giteranyi Rugasa Higiro Rusara Mihigo Gitete Kinyami Munazi Ruheha Muyange Kagugo Bisiga Rumandari Gitwe Kibonde Gisenyi Buhoro Rukungere NByakuizu soni Muvyuko Gasenyi Kididiri Nonwe Giteryani 2°30'0"S 2°30'0"S Kigoma Runyonza Yaranda Burara Nyabugeni Bunywera Rugese Mugendo Karambo Kinyovu Nyabibugu Rugarama Kabanga Cewe Renga Karugunda Rurira Minyago Kabizi Kirundo Rutabo Buringa Ndava Kavomo Shoza Bugera Murore Mika Makombe Kanyagu Rurende Buringanire Murama Kinyangurube Mwenya Bwambarangwe Carubambo Murungurira Kagege Mugobe Shore Ruyenzi Susa Kanyinya Munyinya Ruyaga Budahunga Gasave Kabogo Rubenga Mariza Sasa Buhimba Kirundo Mugongo Centre-Urbain Mutara Mukerwa Gatemere Kimeza Nyemera Gihosha Mukenke Mangoma Bigombo Rambo Kirundo Gakana Rungazi Ntega Gitwenzi Kiravumba Butegana Rugese Monge Rugero Mataka Runyinya Gahosha Santunda Kigaga Gasave Mugano Rwimbogo Mihigo Ntega Gikuyo Buhevyi Buhorana Mukoni Nyempundu Gihome KanabugireGatwe Karamagi Nyakibingo KIRUCNanika DGaOsuga Butahana Bucana Mutarishwa Cumva Rabiro Ngoma Gisitwe Nkorwe Kabirizi Gihinga Miremera Kiziba Muyinza Bugorora Kinyuku Mwendo Rushubije Busenyi Butihinda -

Economic and Social Council in Decision 1995/219, Adopted at Its Resumed Organizational Session for 1995 on 4 May 1995, in New York

UNITED NATIONS E Economic and Social Distr. GENERAL Council E/CN.4/1996/16 14 November 1995 ENGLISH Original: FRENCH COMMISSION ON HUMAN RIGHTS Fifty-second session Item 3 of the provisional agenda ORGANIZATION OF THE WORK OF THE SESSION Initial report on the human rights situation in Burundi submitted by the Special Rapporteur, Mr. Paulo Sérgio Pinheiro, in accordance with Commission resolution 1995/90 CONTENTS Paragraphs Page INTRODUCTION ....................... 1- 9 3 I. THE OVERALL SITUATION............... 10- 43 5 A. The political and institutional crisis .... 10- 18 5 B. Some keys to understanding the concept of "ethnic" racism and the policies deriving from it ............... 19- 21 6 C. Economic hardship and the aggravation of poverty.................... 22- 24 7 D. The fragility of democratic institutions . 25 - 38 8 E. The first steps towards a civilian society . 39 - 43 11 GE.95-14419 (E) E/CN.4/1996/16 page 2 CONTENTS (continued) Paragraphs Page II. OBSERVATIONS ON THE HUMAN RIGHTS SITUATION .... 44-117 12 A. The resurgence of violence and insecurity . 44 - 55 12 B. Violations of the right to life and physical integrity................... 56- 98 14 C. The right to liberty of movement and freedom to choose one’s residence within a State . 99 - 101 21 D. Arbitrary detentions ............. 102-109 21 E. Freedom of expression and freedom of the press .................. 110-117 23 III. FINAL OBSERVATIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS ...... 118-170 25 A. Final observations .............. 118-143 25 B. Recommendations................ 144-170 30 E/CN.4/1996/16 page 3 Introduction 1. In this report, the Special Rapporteur summarizes the initial impressions he formed during his first mission to Burundi, which he will develop and refine in his subsequent reports to the Commission on Human Rights. -

Communal Shelters Built

Contents 1 Executive Summary Objective 1 Food Security 1.1 1 Overview 1.1 11 Performance 1.IV Resources Objective 2 Emergency Shelter 2.1 1 Overview 2.111 Performance 2.IV Resources Appendices 1. Financial Report 2. Objective 1 workplan 3. Group contract 4. Impact evaluation 5. Inputs (a) Seeds (b) Cemicals (c) Animals (d) Tools 6. (a) Buranbi (b) Buyengero 7. Emergency Shelter Map sweetpotato Crop, Butare I EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Organization: Concern Worldwide Inc, New York Mailing Address: 104 East 40th Street, Room 903 New York, NY 10016 Contact Person: Rob Williams International Development Manager Telephone: 2125578000 Fax: 2125578004 Email Address: rob.williams@concern-ny .org Program Title: Community Food Security Program for Vulnerable Families Grant No. AOT-G-00-99-00183-00 Country: Burundi Obiective 1 Food Security in Bururi Province Emergency relief in Bujumbura Rurale Within the past six years Bururi Province 20,000 blankets have been distributed to a in southern Burundi has been seriously target population of 10,000 families. The affected by insecurity. The results of erection of 51 communal hangars has hostilities have been mass population provided shelter to a target population of displacement, damage to infrastructure 4,794 people amongst the most vulnerable and essential services, restricted access to in the regrouped sites of Bujumbura Rural agricultural land and seeds and tool, all of Province. which has lead to a steady decline in the population's access to food, health and Both activities have contributed towards an nutritional status. Improved security in improved quality of life for this target some areas has enabled some families to population in Bujumbura Rural. -

Etude Environnementale De La Reserve Naturelle Forestiere De Bururi

Association Protection des Ressources Naturelles pour le Bien-Etre de la Population au Burundi ______APRN/BEPB______ ETUDE ENVIRONNEMENTALE DE LA RESERVE NATURELLE FORESTIERE DE BURURI KAKUNZE Alain Charles Consultant ________CEPF________ Bujumbura, Janvier 2015 1 Etude environnementale de la Réserve Naturelle de Bururi Document élaboré dans le cadre du projet: Gestion Intégré de la Réserve Naturelle Forestière de Bururi Exécuté par : Association Protection des Ressources Naturelles pour le Bien-Etre de la Population au Burundi (APRN/BEPB) Sous le financement du 2 Etude environnementale de la Réserve Naturelle de Bururi TABLE DES MATIERES SIGLES ET ABBREVIATIONS ..................................................................................................................... 6 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................................... 7 I. PRESENTATION DE LA RESERVE NATURELLE FORESTIERE DE BURURI ........... 10 I.1. ASPECTS PHYSIQUES ....................................................................................................................................10 I.1.1. Géographie .............................................................................................................................................................. 10 I.1.2. Relief ....................................................................................................................................................................... 11 I.1.3. Pédologie -

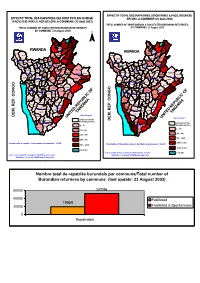

Nombre Total De Rapatriés Burundais Par Commune/Total Number of Burundian Returnees by Commune (Last Update: 23 August 2003)

EFFECTIF TOTAL DES RAPATRIES (SPONTANES & FACILITES/HCR) EFFECTIF TOTAL DES RAPATRIES QUI SONT PRIS EN CHARGE SELON LA COMMUNE (23 Août 2003) (FACILITES) PAR LE HCR SELON LA COMMUNE (23 Août 2003) TOTAL NUMBER OF SPONTANEOUS & FACILITATED BURUNDIAN RETURNEES TOTAL NUMBER OF FACILITATED BURUNDIAN RETURNEES BY COMMUNE ( 23 August 2003) BY COMMUNE ( 23 August 2003) N Bugabira Gi t er anyi Gi t er anyi Busoni Bugabira Bwambarangwe Busoni Ntega Kirundo Kirundo Bwambar angwe RWANDA Kirundo Gi tobe RWANDA Ntega Mugi na Kirundo Butihinda Mabayi Vu mb i Mugina Gi t obe Marangara Gashoho Muyinga Vu mb i Butihinda Rugombo Nyamurenza Mabayi Muyinga Marangar a Gasho ho Mwumba Kiremba Cibitoke Kabarore Muyinga Bukinanyana Busiga Gasor we Rugombo Cibitoke Nyamurenza Mur wi Gashikanwa Mwumba Kayanza Kiremba Gasor we Kabarore Busiga Mur uta Gaho mb o Ngozi Tangara Bukinanyana Gashi kan wa Muyinga Ngozi Gi t ar amu ka Buhinyuza Mur wi Buganda Kayanza Kayanza Ngozi Ruhororo Mur uta Tangara Gatara Muhanga Gaho mb o Gi t ar amu ka Buhi nyuza Bubanza Buhi ga Kigamba Buganda Gatara Ngozi Matongo Bugenyuzi Musigati Kayanza Ruhororo Butaganzwa 1 Mwaki ro Bubanza Buhiga Kigamba Gi hogazi Mishi ha Musigati Matongo Muhanga Bugenyuzi Bubanza Mutaho Cankuzo Mwaki ro Rango Karuzi Butaganzwa 1 Mishi ha Mpanda Bukeye Mutumba Gi sag ar a Bubanza Mutaho Gi hog az i Gi hanga Rango Cankuzo Rugazi Mbuye Shombo Cankuzo Mpanda Karuzi Mutumba Muramvya Bugendana Bukeye Cankuzo Gi sag ar a Nyabikere Cendajuru Gihanga Mbuye Mutimbuzi Muramvya Rutegama Rugazi Bugendana Mubi mbi -

World Bank Document

|LI t!]LILIE []LJiFJLflLiLLiLL!1 H 1i I LI LiLIiIIJ[l]lJ]L]I I I 1-1HII II 171 I' (C- \ "\ 11L- l1-ofl 1lllsU.jU11 J0L LI LI. fU IS1Jr 11 . 11'- >/t?)11 9< | Public Disclosure Authorized MICROFICHE COPY Report No. 9215-BU Type: (SEC) MR. MICHAE/ X34009 / J10205/ AF3 Public Disclosure Authorized Burundi Rommas md optogo$ A th Energ Sector Report No. 9215-BU Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized JOINT UNDP / WORLDBANK ENERGY SECTOR MANAGEMENT ASSISTANCE PROGRAMME (ESMAP) PURPOSE The Joint UNDP/World Bank Energy Sector ManagementAssistance Programme (ESMAP) was launched in 1983 to complementthe Energy AssessmentProgramme, tstablished three years earlier. ESMAP's original purpose was to implementkey recommendationsof the Energy Assessmentreports and ensure that proposed investmentsin the energy sector representedthe most efficientuse of scarce domesticand external resources. In 1990, an internationalCommission addressed ESMAP's role for the 1990sand, noting the vital role of adequateand affordableenergy in economicgrowth, concluded that the Programme should intensify its efforts to assist developingcountries to manage their energy sectors more effectively. The Commissionalso recommendedthat ESMAP concentrate on making long-term efforts in a smaller number of countries. the Commission's report was endorsed at ESMAP's November1990 AnnualMeeting and promptedan extensivereorganization and reorientation of the Programme. Today, ESMAP is conductingEnergy Assessments,performing preinvestment and prefeasibilitywork, and providing institutionaland policy advice in selected developing countries. Through these efforts, ESMAP aims to assist governments, donors, and potential investors in identifying,funding, and implcmentingeconomically and environmentallysound energy strategies. GOVERNANCE AND OPERATIONS ESMAPis governedby a ConsultativeGroup (ESMAPCG), composedof representativesof the UNDP and World Bank, the govemmentsand institutionsproviding financialsupport, and representativesof the recipientsof ESMAP's assistance. -

Evaluation Des Recoltes De La Saison 2017B Et De La Mise En Place De La Saison 2017C

EVALUATION DES RECOLTES DE LA SAISON 2017B ET DE LA MISE EN PLACE DE LA SAISON 2017C Stock de maïs et haricot de la Coopérative NAWENUZE, Province Kirundo, Commune Busoni, juin 2017. Septembre 2017 Table des matières Liste des abréviations et acronymes .............................................................................................. 3 INTRODUCTION GENERALE ................................................................................................... 4 PARTIE I: EVALUATION DES RECOLTES DE LA SAISON 2017B ......................................... 5 I.1. PRINCIPAUX FACTEURS AYANT INFLUENCÉ LA SAISON 2017B ........................... 6 I.1.1. La pluviométrie et aléas .............................................................................................. 6 I.1.2. La disponibilité des intrants agricoles ......................................................................... 7 I.1.3. Les maladies et ravageurs des plantes ......................................................................... 8 I.2. NIVEAUX DES PRODUCTIONS POUR LA SAISON 2017B ......................................... 17 I.2.1. Productions vivrières par groupe de cultures ............................................................ 17 I.2.2. Production vivrière estimée par habitant ................................................................... 22 I.2.3. Comparaison de la production de la saison 2017B avec les saisons B antérieures (2012- 2016) ...........................................................................................................................