ARSC Journal, VIII:2-3, P

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Karl Schuricht Concerto En Ré Majeur - Op

Karl Schuricht Concerto En Ré Majeur - Op. 77 Pour Violon Et Orchestre mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Classical Album: Concerto En Ré Majeur - Op. 77 Pour Violon Et Orchestre Country: France Style: Romantic MP3 version RAR size: 1276 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1586 mb WMA version RAR size: 1954 mb Rating: 4.2 Votes: 930 Other Formats: XM AA APE FLAC AIFF ASF WAV Tracklist Concerto En Ré Majeur - Op. 77 Pour Violon Et Orchestre A1 Allegro Non Troppo (Cadence De Kreisler) B1 Adagio Allegro Giocoso, Ma Non Troppo Vivace (Cadence De B2 Kreisler) Companies, etc. Printed By – Dehon & Cie Imp. Paris Credits Liner Notes – Claude Rostand Barcode and Other Identifiers Rights Society: DP Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year Johannes Brahms, Johannes Brahms, Christian Ferras, Christian Ferras, Wiener Philharmoniker, LXT 2949 Wiener Carl Schuricht - Decca LXT 2949 UK Unknown Philharmoniker, Carl Concerto In D Major For Schuricht Violin And Orchestra Opus 77 (LP, Album) Carl Schuricht - Carl Schuricht - Christian Ferras - Christian Ferras - 6.42142 Johannes Brahms - 6.42142 Johannes Brahms - Decca Germany Unknown AF Wiener Philharmoniker - AF Wiener Violinkonzert D-Dur (LP, Philharmoniker Album) Carl Schuricht - Christian Ferras - Carl Schuricht - Johannes Brahms - Christian Ferras - Wiener Philharmoniker - LXT 2949 Johannes Brahms - Decca LXT 2949 Spain 1958 Concierto En "Re" Wiener Mayor Para Violín y Philharmoniker Orquesta Opus 71 (LP, Album, Mono) Johannes Brahms, Christian Ferras, Vienna Johannes Brahms, Philharmonic Christian Ferras, Orchestra*, Carl B 19018 Vienna Philharmonic Richmond B 19018 Mexico Unknown Schuricht - Concerto In Orchestra*, Carl D Major For Violin And Schuricht Orchestra Opus 77 (LP, Album) Carl Schuricht - Carl Schuricht - Christian Ferras - Christian Ferras - LW 50095 Johannes Brahms - Johannes Brahms - Decca LW 50095 Germany Unknown Wiener Wiener Philharmoniker - Philharmoniker Violinkonzert D-Dur (LP) Related Music albums to Concerto En Ré Majeur - Op. -

Multivalent Form in Gustav Mahlerʼs Lied Von Der Erde from the Perspective of Its Performance History

Multivalent Form in Gustav Mahlerʼs Lied von der Erde from the Perspective of Its Performance History Christian Utz All content is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Received: 09/10/2017 Accepted: 19/11/2017 Published: 27/02/2018 Last updated: 27/02/2018 How to cite: Christian Utz, “Multivalent Form in Gustav Mahlerʼs Lied von der Erde from the Perspective of Its Performance History,” Musicologica Austriaca: Journal for Austrian Music Studies (February 27, 2018) Tags: 20th century; Analysis; Bernstein, Leonard; Das Lied von der Erde; Klemperer, Otto; Mahler, Gustav; Performance; Performance history; Rotational form; Sonata form; Strophic form; Walter, Bruno This essay is an expanded version of a paper presented at the symposiumGustav Mahler im Dialog, held at the Gustav Mahler Musikwochen in Toblach/Dobbiaco on July 18, 2017. The research was developed as part of the research project Performing, Experiencing and Theorizing Augmented Listening [PETAL]. Interpretation and Analysis of Macroform in Cyclic Musical Works (Austrian Science Fund (FWF): P 30058-G26; 2017–2020). I am grateful for advice received from Federico Celestini, Peter Revers, Thomas Glaser, and Laurence Willis. Files for download: Tables and Diagrams, Video examples 1-2, Video examples 3-4, Video examples 5-8, Video examples 9-10 Best Paper Award 2017 Abstract The challenge of reconstructing Gustav Mahlerʼs aesthetics and style of performance, which incorporated expressive and structuralist principles, as well as problematic implications of a post- Mahlerian structuralist performance style (most prominently developed by the Schoenberg School) are taken in this article as the background for a discussion of the performance history of Mahlerʼs Lied von der Erde with the aim of probing the model of “performance as analysis in real time” (Robert Hill). -

Universi^ Aaicronlms Intemationêd

INFORMATION TO USERS This reproduction was made from a copy of a document sent to us for microfilming. While the most advanced technology has been used to photograph and reproduce this document, the quality of the reproduction is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help clarify markings or notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or “target” for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is “Missing Page(s)”. If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting through an image and duplicating adjacent pages to assure complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a round black mark, it is an indication of either blurred copy because of movement during exposure, duplicate copy, or copyrighted materials that should not have been filmed. For blurred pages, a good image of the page can be found in the adjacent frame. If copyrighted materials were deleted, a target note will appear listing the pages in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., is part of the material being photographed, a definite method of “sectioning” the material has been followed. It is customary to begin filming at the upper left hand comer of a large sheet and to continue from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. If necessary, sectioning is continued again—beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. -

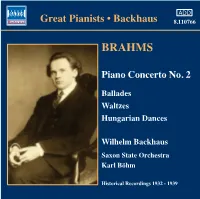

110766 Bk Backhaus EU 17/06/2004 11:23Am Page 4

110766 bk Backhaus EU 17/06/2004 11:23am Page 4 Johannes Brahms (1833-1897) Waltzes, Op. 39 ADD Piano Concerto No. 2 in B flat major, Op. 83 7 No. 1 in B major 0:50 Great Pianists • Backhaus 8.110766 8 No. 2 in E major 1:12 1 Allegro non troppo 16:04 9 No. 3 in G sharp minor 0:43 2 Allegro appassionato 8:05 0 No. 4 in E minor 0:30 3 Andante 11:53 ! No. 5 in E major 1:01 4 Allegretto grazioso 9:06 @ No. 6 in C sharp major 0:53 # No. 7 in C sharp minor 1:10 Saxon State Orchestra • Karl Böhm $ No. 8 in B flat major 0:35 BRAHMS % No. 9 in D minor 0:50 Recorded June, 1939 in Dresden ^ No. 10 in G major 0:29 Matrices: 2RA 3956-2, 3957-1, 3958-1, 3959-3A, & No. 11 in B minor 0:39 3960-1, 3961-1A, 3962-1, 3963-3, 3964-3A, * No. 12 in E major 0:49 3965-2, 3966-2 and 3967-1 ( No. 13 in B major 0:26 First issued on HMV DB 3930 through 3935 ) No. 14 in G sharp minor 0:36 Piano Concerto No. 2 ¡ No. 15 in A flat major 1:18 Ballades, Op. 10 ™ No. 16 in C sharp minor 1:10 5 No. 1 in D minor (“Edward”) 4:07 Recorded 27th January, 1936 6 No. 2 in D major 4:59 in EMI Abbey Road Studio No. 3 Ballades Matrices: 2EA 3010-5, 3011-5 and 3012-4 Recorded 5th December, 1932 First issued on HMV DB 2803 and 2804 in EMI Abbey Road Studio No. -

Pdf 139.3 Kb

Dresdner Philharmonie The Dresden Philharmonic can look back on 150 years of history as the orchestra of Saxony’s capital Dresden. When the so-called “Gewerbehaussaal” opened on 29 November 1870, the citizens of the city were given the opportunity to organise major orchestra concerts. Philharmonic concerts were held regularly starting in 1885; the orchestra adopted its present name in 1923. In its first decades, composers such as Brahms, Tchaikovsky, Dvořák and Strauss conducted the Dresdner Philharmonie with their own works. The first desks were presided over by outstanding concertmasters such as Stefan Frenkel, Simon Goldberg and the cellists Stefan Auber and Enrico Mainardi. From 1934, Carl Schuricht and Paul van Kempen led the orchestra; van Kempen in particular guided the Dresden Philharmonic to top achievements. All of Bruckner’s symphonies were first performed in their original versions, which earned the orchestra the reputation of a “Bruckner orchestra” and brought renowned guest conductors such as Hermann Abendroth, Eduard van Beinum, Fritz Busch, Eugen Jochum, Joseph Keilbert, Erich Kleiber, Hans Knappertsbusch and Franz Konwitschny to the rostrum. After 1945 and into the 1990s, Heinz Bongartz, Horst Förster, Kurt Masur (from 1994 also honorary conductor), Günther Herbig, Herbert Kegel, Jörg-Peter Weigle and Michel Plasson were the principal conductors. In recent years, conductors such as Marek Janowski, Rafael Frühbeck de Burgos and Michael Sanderling have shaped the orchestra. As of season 2019/2020, Marek Janowski has returned to the Dresden Philharmonic as principal conductor and artistic director. Its home is the highly modern concert hall inaugurated in April 2017 in the Kulturpalast building in the heart of the historic old town. -

Carl Schuricht Collection II Radio-Sinfonieorchester Stuttgart Historical Recordings 1951 – 1966 02 CD 1 CD 3 CD 5 CD 7 03

Carl SChuriCht ColleCtion II Radio-Sinfonieorchester Stuttgart Historical Recordings 1951 – 1966 02 CD 1 CD 3 CD 5 CD 7 03 LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN JOHANNES BRAHms CARL MARIA V. WEBER (1786 – 1826) 1 (1770–1827) Sinfonie Nr. 6 F-Dur op. 68 Sinfonie Nr. 4 e-Moll op. 98 [43:46] Ouvertüre zur Oper Euryanthe [08:46] 1 2 Sinfonie Nr. 1 C-Dur op. 21 [23:29] (Pastorale) [37:29] I Allegro non troppo [13:32] Ouvertüre zur Oper Oberon [09:32] 1 I Adagio molto – Allegro con brio [08:24] 1 I Erwachen heiterer Gefühle 2 II Andante moderato [12:20] Deutsch 2 II Satz: Andante cantabile con moto [05:40] bei der Ankunft auf dem Lande. 3 III Allegro giocoso [06:47] HUGO WOLF (1860 – 1903) 3 III Satz: Menuetto. Allegro ma non troppo [09:27] 4 IV Allegro energico e passionato [11:07] 3 Italienische Serenade G-Dur Allegro molto e vivace [03:28] 2 II Szene am Bach. für kleines Orchester [07:17] 4 IV Finale. Andante molto mosso [12:50] JOHANNES BRAHms Adagio – Allegro molto e vivace [05:57] 3 III Lustiges Zusammensein der 5 Rhapsodie für Alt, Männerchor PETER TsCHAIKOWSKY (1840 – 1893) Landleute. Allegro. attacca [03:07] und Orchester op. 53 [12:16] 4 Hamlet. Fantasie-Ouvertüre LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN 4 IV Gewitter, Sturm. Allegro. attacca [03:36] für Orchester op. 67 [19:05] Sinfonie Nr. 3 Es-Dur op. 55 (Eroica) [45:56] 5 V Hirtengesang. JOHANNES BRAHms 5 I Allegro con brio [13:57] Frohe und dankbare Gefühle nach 6 Tragische Ouvertüre d-Moll op. -

Persecution, Collaboration, Resistance

Münsteraner Schriften zur zeitgenössischen Musik 5 Ina Rupprecht (ed.) Persecution, Collaboration, Resistance Music in the ›Reichskommissariat Norwegen‹ (1940–45) Münsteraner Schrift en zur zeitgenössischen Musik Edited by Michael Custodis Volume 5 Ina Rupprecht (ed.) Persecution, Collaboration, Resistance Music in the ‘Reichskommissariat Norwegen’ (1940–45) Waxmann 2020 Münster x New York The publication was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft , the Grieg Research Centre and the Westfälische Wilhelms-Universität Münster as well as the Open Access Publication Fund of the University of Münster. Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek Th e Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografi e; detailed bibliographic data are available in the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de Münsteraner Schrift en zur zeitgenössischen Musik, Volume 5 Print-ISBN 978-3-8309-4130-9 E-Book-ISBN 978-3-8309-9130-4 DOI: https://doi.org/10.31244/9783830991304 CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 Waxmann Verlag GmbH, 2020 Steinfurter Straße 555, 48159 Münster www.waxmann.com [email protected] Cover design: Pleßmann Design, Ascheberg Cover pictures: © Hjemmefrontarkivet, HA HHI DK DECA_0001_44, saddle of sources regarding the Norwegian resistance; Riksarkivet, Oslo, RA/RAFA-3309/U 39A/ 4/4-7, img 197, Atlantic Presse- bilderdienst 12. February 1942: Th e newly appointed Norwegian NS prime minister Vidkun Quisling (on the right) and Reichskomissar Josef Terboven (on the left ) walking along the front of an honorary -

ASIAN SYMPHONIES a Discography of Cds and Lps Prepared By

ASIAN SYMPHONIES A Discography Of CDs And LPs Prepared by Michael Herman Edited by Stephen Ellis KOMEI ABE (1911-2006, JAPAN) Born in Hiroshima. He studied the cello with Heinrich Werkmeister at the Tokyo Music School and then studied German-style harmony and counterpoint with Klaus Pringsheim, a pupil of Gustav Mahler, as well as conducting with Joseph Rosenstock. Later, he was appointed music director of the Imperial Orchestra in Tokyo, and the musicians who played under him broadened his knowledge of traditional Japanese Music. He then taught at Kyoto's Elizabeth Music School and Municipal College of the Arts. He composed a significant body of orchestral, chamber and vocal music, including a Symphony No. 2 (1960) and Piccolo Sinfonia for String Orchestra (1984). Symphony No. 1 (1957) Dmitry Yablonsky/Russian National Philharmonic ( + Sinfonietta and Divertimento) NAXOS 8.557987 (2007) Sinfonietta for Orchestra (1964) Dmitry Yablonsky/Russian National Philharmonic ( + Sinfonietta and Divertimento) NAXOS 8.557987 (2007) NICANOR ABELARDO (1896-1934, PHILIPPINES) Born in San Miguel, Bulacan. He studied at the University of the Philippines Diliman Conservatory of Music, taking courses under Guy Fraser Harrison and Robert Schofield. He became head of the composition department of the conservatory in 1923. He later studied at the Chicago Musical College in 1931 under Wesley LaViolette. He composed orchestral and chamber works but is best-known for his songs. Sinfonietta for Strings (1932) Ramon Santos/Philippine Philharmonic Orchestra UNIVERSITY OF THE PHILIPPINES PRESS (2004) YASUSHI AKUTAGAWA (1925-1989, JAPAN) He was born in the Tabata section of Tokyo. He was taught composition by Kunihiko Hashimoto and Akira Ifukube at the Tokyo Conservatory of Music. -

Bruckner Symphony Cycles (Not Commercially Available As Recordings) Compiled by John F

Bruckner Symphony Cycles (not commercially available as recordings) Compiled by John F. Berky – June 3, 2020 (Updated May 20, 2021) 1910 /11 – Ferdinand Löwe – Wiener Konzertverein Orchester 1] 25.10.10 - Ferdinand Loewe 1] 24.01.11 - Ferdinand Loewe (Graz) 2] 02.11.10 - Martin Spoerr 2] 20.11.10 - Martin Spoerr 2] 29.04.11 - Martin Spoerr (Bamberg) 3] 25.11.10 - Ferdinand Loewe 3] 26.11.10 - Ferdinand Loewe 3] 08.01.11 - Gustav Gutheil 3] 26.01.11- Ferdinand Loewe (Zagreb) 3] 17.04.11 - Ferdinand Loewe (Budapest) 4] 07.01.11 - Hans Maria Wallner 4] 12.02.11 - Martin Spoerr 4] 18.02.11 - Hans Maria Wellner 4] 26.02.11 - Hans Maria Wallner 4] 02.03.11 - Hans Maria Wallner 4] 23.04.11 - Franz Schalk 5] 05.02.11 - Ferdinand Loewe 6] 21.02.11 - Ferdinand Loewe 7] 03.03.11 - Ferdinand Loewe 7] 17.03.11 - Ferdinand Loewe 7] 02.04.11 - Ferdinand Loewe 8] 23.02.11 - Oskar Nedbal 8] 12.03.11 - Ferdinand Loewe 9] 24.03.11 - Ferdinand Loewe 1910/11 – Ferdinand Löwe – Munich Philharmonic 1] 17.10.10 - Ferdinand Loewe 2] 14.11.10 - Ferdinand Loewe 3] 21.11.10 - Ferdinand Loewe (Fassung 1890) 4] 09.01.11 - Ferdinand Loewe (Fassung 1889) 5] 30.01.11 - Ferdinand Loewe 6] 13.02.11 - Ferdinand Loewe 7] 27.02.11 - Ferdinand Loewe 8] 06.03.11 - Ferdinand Loewe (with Psalm 150 -Charles Cahier) 9] 10.04.11 - Ferdinand Loewe (with Te Deum) 1919/20 – Arthur Nikisch – Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra 1] 09.10.19 - Artur Nikisch (1. -

Concerts Conducted by Carl Schuricht Including Music of Anton Bruckner (1912-1965) Original Source

Concerts conducted by Carl Schuricht including music of Anton Bruckner (1912-1965) Original source : http://carlschuricht.com/concert.htm Important Dates 3 July 1880 : Carl Adolph Schuricht was born at Danzig (Gdansk) into a family of organ-builders. His father, Carl Conrad Schuricht was born on 27 January 1856. He was an organ-builder and worked at his father's factory. He died on 9 June 1880 (3 weeks before his son was born !) when he tried to help an employee fallen into the sea, in the bay of Danzig. His mother, Amanda Ludowika Alwine Wusinowska was a well-known Polish Oratorio singer (1847-1935) . She didn't re-marry after her husband's death. 1886 : Began piano and violin lessons at the age of 6. Studied at the « Friedrichs Realgymnasium » in Berlin. 1891 : Began to compose at the age of 11. 1892 : Studied at the « Königliches Realgymnasium » in Wiesbaden. Written the music and the librettos for 2 Operas. 1895 : Started conducting at the age of 15. 1901-1902 : 1st professional job as « Korrepetitor » at the « Stadttheater » of Mainz. 1902 : Won a composition prize from the Kuszynski Foundation, and awarded a scholarship by Franz von Mendelssohn. Allowed him to continue his studies at the « Berliner Musikhochschule » (« der Königlichten Hochschule für Musik ») under Ernst Rudorff, piano ; Heinrich van Eyken (and not Engelbert Humperdink) , composition ; and, later, Max Reger in Leipzig. His musical compositions were published mostly by Drei-Lilien-Verlag, Berlin. Opus 1 : Piano Sonata in F minor. Opus 2 : « Herbst-Stücke » (Opuscules for autumn) for piano and orchestra. Opus 3 : « Fünf Lieder » (5 Songs) . -

USHMM Finding

http://collections.ushmm.org Contact [email protected] for further information about this collection MARIAN FILAR [1-1-1] THIS IS AN INTERVIEW WITH: MF - Marian Filar [interviewee] EM - Edith Millman [interviewer] Interview Dates: September 5, and November 16, 1994, June 16, 1995 Tape one, side one: EM: This is Edith Millman interviewing Professor Marian Filar. Today is Septem- ber 5, 1994. We are interviewing in Philadelphia. Professor Filar, would you tell me where you were born and when, and a little bit about your family? MF: Well, I was born in Warsaw, Poland, before the Second World War. My father was a businessman. He actually wanted to be a lawyer, and he made the exam on the university, but he wasn’t accepted, but he did get an A, but he wasn’t accepted. EM: Could you tell me how large your family was? MF: You mean my general, just my immediate family? EM: Yeah, your immediate family. How many siblings? MF: We were seven children. I was the youngest. I had four brothers and two sis- ters. Most of them played an instrument. My oldest brother played a violin, the next to him played the piano. My sister Helen was my first piano teacher. My sister Lucy also played the piano. My brother Yaacov played a violin. So there was a lot of music there. EM: I just want to interject that Professor Filar is a known pianist. Mr.... MF: Concert pianist. EM: Concert pianist. Professor Filar, could you tell me what your life was like in Warsaw before the war? MF: Well, it was fine. -

Decca Discography

DECCA DISCOGRAPHY >>V VIENNA, Austria, Germany, Hungary, etc. The Vienna Philharmonic was the jewel in Decca’s crown, particularly from 1956 when the engineers adopted the Sofiensaal as their favoured studio. The contract with the orchestra was secured partly by cultivating various chamber ensembles drawn from its membership. Vienna was favoured for symphonic cycles, particularly in the mid-1960s, and for German opera and operetta, including Strausses of all varieties and Solti’s “Ring” (1958-65), as well as Mackerras’s Janá ček (1976-82). Karajan recorded intermittently for Decca with the VPO from 1959-78. But apart from the New Year concerts, resumed in 2008, recording with the VPO ceased in 1998. Outside the capital there were various sessions in Salzburg from 1984-99. Germany was largely left to Decca’s partner Telefunken, though it was so overshadowed by Deutsche Grammophon and EMI Electrola that few of its products were marketed in the UK, with even those soon relegated to a cheap label. It later signed Harnoncourt and eventually became part of the competition, joining Warner Classics in 1990. Decca did venture to Bayreuth in 1951, ’53 and ’55 but wrecking tactics by Walter Legge blocked the release of several recordings for half a century. The Stuttgart Chamber Orchestra’s sessions moved from Geneva to its home town in 1963 and continued there until 1985. The exiled Philharmonia Hungarica recorded in West Germany from 1969-75. There were a few engagements with the Bavarian Radio in Munich from 1977- 82, but the first substantial contract with a German symphony orchestra did not come until 1982.