My Sixth Seems to Be Yet Another Hard Nut, One That Our Critics' Feeble Little

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gustav Mahler : Conducting Multiculturalism

GUSTAV MAHLER : CONDUCTING MULTICULTURALISM Victoria Hallinan 1 Musicologists and historians have generally paid much more attention to Gustav Mahler’s famous career as a composer than to his work as a conductor. His choices in concert repertoire and style, however, reveal much about his personal experiences in the Austro-Hungarian Empire and his interactions with cont- emporary cultural and political upheavals. This project examines Mahler’s conducting career in the multicultural climate of late nineteenth-century Vienna and New York. It investigates the degree to which these contexts influenced the conductor’s repertoire and questions whether Mahler can be viewed as an early proponent of multiculturalism. There is a wealth of scholarship on Gustav Mahler’s diverse compositional activity, but his conducting repertoire and the multicultural contexts that influenced it, has not received the same critical attention. 2 In this paper, I examine Mahler’s connection to the crumbling, late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century depiction of the Austro-Hungarian Empire as united and question whether he can be regarded as an exemplar of early multiculturalism. I trace Mahler’s career through Budapest, Vienna and New York, explore the degree to which his repertoire choices reflected the established opera canon of his time, or reflected contemporary cultural and political trends, and address uncertainties about Mahler’s relationship to the various multicultural contexts in which he lived and worked. Ultimately, I argue that Mahler’s varied experiences cannot be separated from his decisions regarding what kinds of music he believed his audiences would want to hear, as well as what kinds of music he felt were relevant or important to share. -

ARSC Journal

A Discography of the Choral Symphony by J. F. Weber In previous issues of this Journal (XV:2-3; XVI:l-2), an effort was made to compile parts of a composer discography in depth rather than breadth. This one started in a similar vein with the realization that SO CDs of the Beethoven Ninth Symphony had been released (the total is now over 701). This should have been no surprise, for writers have stated that the playing time of the CD was designed to accommodate this work. After eighteen months' effort, a reasonably complete discography of the work has emerged. The wonder is that it took so long to collect a body of information (especially the full names of the vocalists) that had already been published in various places at various times. The Japanese discographers had made a good start, and some of their data would have been difficult to find otherwise, but quite a few corrections and additions have been made and some recording dates have been obtained that seem to have remained 1.Dlpublished so far. The first point to notice is that six versions of the Ninth didn't appear on the expected single CD. Bl:lhm (118) and Solti (96) exceeded the 75 minutes generally assumed (until recently) to be the maximum CD playing time, but Walter (37), Kegel (126), Mehta (127), and Thomas (130) were not so burdened and have been reissued on single CDs since the first CD release. On the other hand, the rather short Leibowitz (76), Toscanini (11), and Busch (25) versions have recently been issued with fillers. -

Symposium Programme

Singing a Song in a Foreign Land a celebration of music by émigré composers Symposium 21-23 February 2014 and The Eranda Foundation Supported by the Culture Programme of the European Union Royal College of Music, London | www.rcm.ac.uk/singingasong Follow the project on the RCM website: www.rcm.ac.uk/singingasong Singing a Song in a Foreign Land: Symposium Schedule FRIDAY 21 FEBRUARY 10.00am Welcome by Colin Lawson, RCM Director Introduction by Norbert Meyn, project curator & Volker Ahmels, coordinator of the EU funded ESTHER project 10.30-11.30am Session 1. Chair: Norbert Meyn (RCM) Singing a Song in a Foreign Land: The cultural impact on Britain of the “Hitler Émigrés” Daniel Snowman (Institute of Historical Research, University of London) 11.30am Tea & Coffee 12.00-1.30pm Session 2. Chair: Amanda Glauert (RCM) From somebody to nobody overnight – Berthold Goldschmidt’s battle for recognition Bernard Keeffe The Shock of Exile: Hans Keller – the re-making of a Viennese musician Alison Garnham (King’s College, London) Keeping Memories Alive: The story of Anita Lasker-Wallfisch and Peter Wallfisch Volker Ahmels (Festival Verfemte Musik Schwerin) talks to Anita Lasker-Wallfisch 1.30pm Lunch 2.30-4.00pm Session 3. Chair: Daniel Snowman Xenophobia and protectionism: attitudes to the arrival of Austro-German refugee musicians in the UK during the 1930s Erik Levi (Royal Holloway) Elena Gerhardt (1883-1961) – the extraordinary emigration of the Lieder-singer from Leipzig Jutta Raab Hansen “Productive as I never was before”: Robert Kahn in England Steffen Fahl 4.00pm Tea & Coffee 4.30-5.30pm Session 4. -

IGUSTAV MAHLER Ik STUDY of HIS PERSONALITY 6 WORK

IGUSTAV MAHLER Ik STUDY OF HIS PERSONALITY 6 WORK PAUL STEFAN ML 41O M23S831 c.2 MUSI UNIVERSITY OF TORONTO Presented to the FACULTY OF Music LIBRARY by Estate of Robert A. Fenn GUSTAV MAHLER A Study of His Personality and tf^ork BY PAUL STEFAN TRANSLATED FROM THE GERMAN EY T. E. CLARK NEW YORK : G. SCHIRMER COPYRIGHT, 1913, BY G. SCHIRMER 24189 To OSKAR FRIED WHOSE GREAT PERFORMANCES OF MAHLER'S WORKS ARE SHINING POINTS IN BERLIN'S MUSICAL LIFE, AND ITS MUSICIANS' MOST SPLENDID REMEMBRANCES, THIS TRANSLATION IS RESPECTFULLY DEDICATED BERLIN, Summer of 1912. TRANSLATOR'S PREFACE The present translation was undertaken by the writer some two years ago, on the appearance of the first German edition. Oskar Fried had made known to us in Berlin the overwhelming beauty of Mahler's music, and it was intended that the book should pave the way for Mahler in England. From his appearance there, we hoped that his genius as man and musi- cian would be recognised, and also that his example would put an end to the intolerable existing chaos in reproductive music- making, wherein every quack may succeed who is unscrupulous enough and wealthy enough to hold out until he becomes "popular." The English musician's prayer was: "God pre- serve Mozart and Beethoven until the right man comes," and this man would have been Mahler. Then came Mahler's death with such appalling suddenness for our youthful enthusiasm. Since that tragedy, "young" musicians suddenly find themselves a generation older, if only for the reason that the responsibility of continuing Mah- ler's ideals now rests upon their shoulders in dead earnest. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 130, 2010-2011

BOSTON SYM PHONY • 4 ORCH ESTRA MTSP III __ 2010-2011 SEASON WEEK 1 James Levine Music Director Bernard Haitink Conductor Emeritus Seiji Ozawa Music Director Laureate RMES TALE I S, LIFE AS A ^S Table of Contents Week i 15 BSO NEWS 21 ON DISPLAY IN SYMPHONY HALL 22 BSO MUSIC DIRECTOR JAMES LEVINE 24 THE BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA 27 A BRIEF HISTORY OF THE BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA 33 THIS WEEK'S PROGRAM 35 FROM THE MUSIC DIRECTOR Notes on the Program 39 Gustav Mahler 57 To Read and Hear More... Guest Artists 61 Layla Claire 62 Karen Cargill 64 Tanglewood Festival Chorus 67 John Oliver 70 SPONSORS AND DONORS 80 FUTURE PROGRAMS 82 SYMPHONY HALL EXIT PLAN 83 SYMPHONY HALL INFORMATION THIS WEEK S PRE-CONCERT TALKS ARE GIVEN BY BSO DIRECTOR OF PROGRAM PUBLICATIONS MARC MANDEL (OCTOBER 8, 12) AND ASSISTANT DIRECTOR OF PROGRAM PUBLICATIONS ROBERT KIRZINGER (OCTOBER 7, 9). program copyright ©2010 Boston Symphony Orchestra, Inc. design by Hecht Design, Arlington, MA cover photograph by Michael J. Lutch BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA Symphony Hall, 301 Massachusetts Avenue Boston, MA 02115-4511 (617) 266-1492 bso.org THE JOURNEY TO THE PRIVATE CLOUD STARTS NOW EMC is proud to support the Boston Symphony Orchestra. Learn more atwww.EMC.com/bso. EMC where information lives endary. HARVARD EXTENSION SCHOOL Greek heroes and award-winning faculty. At Harvard Extension School, we have our share of legends. Whether you are interested in ancient mythology or some other awe-inspiring subject, we invite you to check out our evening and online courses. -

Karl Schuricht Concerto En Ré Majeur - Op

Karl Schuricht Concerto En Ré Majeur - Op. 77 Pour Violon Et Orchestre mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Classical Album: Concerto En Ré Majeur - Op. 77 Pour Violon Et Orchestre Country: France Style: Romantic MP3 version RAR size: 1276 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1586 mb WMA version RAR size: 1954 mb Rating: 4.2 Votes: 930 Other Formats: XM AA APE FLAC AIFF ASF WAV Tracklist Concerto En Ré Majeur - Op. 77 Pour Violon Et Orchestre A1 Allegro Non Troppo (Cadence De Kreisler) B1 Adagio Allegro Giocoso, Ma Non Troppo Vivace (Cadence De B2 Kreisler) Companies, etc. Printed By – Dehon & Cie Imp. Paris Credits Liner Notes – Claude Rostand Barcode and Other Identifiers Rights Society: DP Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year Johannes Brahms, Johannes Brahms, Christian Ferras, Christian Ferras, Wiener Philharmoniker, LXT 2949 Wiener Carl Schuricht - Decca LXT 2949 UK Unknown Philharmoniker, Carl Concerto In D Major For Schuricht Violin And Orchestra Opus 77 (LP, Album) Carl Schuricht - Carl Schuricht - Christian Ferras - Christian Ferras - 6.42142 Johannes Brahms - 6.42142 Johannes Brahms - Decca Germany Unknown AF Wiener Philharmoniker - AF Wiener Violinkonzert D-Dur (LP, Philharmoniker Album) Carl Schuricht - Christian Ferras - Carl Schuricht - Johannes Brahms - Christian Ferras - Wiener Philharmoniker - LXT 2949 Johannes Brahms - Decca LXT 2949 Spain 1958 Concierto En "Re" Wiener Mayor Para Violín y Philharmoniker Orquesta Opus 71 (LP, Album, Mono) Johannes Brahms, Christian Ferras, Vienna Johannes Brahms, Philharmonic Christian Ferras, Orchestra*, Carl B 19018 Vienna Philharmonic Richmond B 19018 Mexico Unknown Schuricht - Concerto In Orchestra*, Carl D Major For Violin And Schuricht Orchestra Opus 77 (LP, Album) Carl Schuricht - Carl Schuricht - Christian Ferras - Christian Ferras - LW 50095 Johannes Brahms - Johannes Brahms - Decca LW 50095 Germany Unknown Wiener Wiener Philharmoniker - Philharmoniker Violinkonzert D-Dur (LP) Related Music albums to Concerto En Ré Majeur - Op. -

Multivalent Form in Gustav Mahlerʼs Lied Von Der Erde from the Perspective of Its Performance History

Multivalent Form in Gustav Mahlerʼs Lied von der Erde from the Perspective of Its Performance History Christian Utz All content is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Received: 09/10/2017 Accepted: 19/11/2017 Published: 27/02/2018 Last updated: 27/02/2018 How to cite: Christian Utz, “Multivalent Form in Gustav Mahlerʼs Lied von der Erde from the Perspective of Its Performance History,” Musicologica Austriaca: Journal for Austrian Music Studies (February 27, 2018) Tags: 20th century; Analysis; Bernstein, Leonard; Das Lied von der Erde; Klemperer, Otto; Mahler, Gustav; Performance; Performance history; Rotational form; Sonata form; Strophic form; Walter, Bruno This essay is an expanded version of a paper presented at the symposiumGustav Mahler im Dialog, held at the Gustav Mahler Musikwochen in Toblach/Dobbiaco on July 18, 2017. The research was developed as part of the research project Performing, Experiencing and Theorizing Augmented Listening [PETAL]. Interpretation and Analysis of Macroform in Cyclic Musical Works (Austrian Science Fund (FWF): P 30058-G26; 2017–2020). I am grateful for advice received from Federico Celestini, Peter Revers, Thomas Glaser, and Laurence Willis. Files for download: Tables and Diagrams, Video examples 1-2, Video examples 3-4, Video examples 5-8, Video examples 9-10 Best Paper Award 2017 Abstract The challenge of reconstructing Gustav Mahlerʼs aesthetics and style of performance, which incorporated expressive and structuralist principles, as well as problematic implications of a post- Mahlerian structuralist performance style (most prominently developed by the Schoenberg School) are taken in this article as the background for a discussion of the performance history of Mahlerʼs Lied von der Erde with the aim of probing the model of “performance as analysis in real time” (Robert Hill). -

German Jews in the United States: a Guide to Archival Collections

GERMAN HISTORICAL INSTITUTE,WASHINGTON,DC REFERENCE GUIDE 24 GERMAN JEWS IN THE UNITED STATES: AGUIDE TO ARCHIVAL COLLECTIONS Contents INTRODUCTION &ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 1 ABOUT THE EDITOR 6 ARCHIVAL COLLECTIONS (arranged alphabetically by state and then city) ALABAMA Montgomery 1. Alabama Department of Archives and History ................................ 7 ARIZONA Phoenix 2. Arizona Jewish Historical Society ........................................................ 8 ARKANSAS Little Rock 3. Arkansas History Commission and State Archives .......................... 9 CALIFORNIA Berkeley 4. University of California, Berkeley: Bancroft Library, Archives .................................................................................................. 10 5. Judah L. Mages Museum: Western Jewish History Center ........... 14 Beverly Hills 6. Acad. of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences: Margaret Herrick Library, Special Coll. ............................................................................ 16 Davis 7. University of California at Davis: Shields Library, Special Collections and Archives ..................................................................... 16 Long Beach 8. California State Library, Long Beach: Special Collections ............. 17 Los Angeles 9. John F. Kennedy Memorial Library: Special Collections ...............18 10. UCLA Film and Television Archive .................................................. 18 11. USC: Doheny Memorial Library, Lion Feuchtwanger Archive ................................................................................................... -

Verklärte Nacht Works for Piano Trio Osiris Trio

ARNOLD SCHÖNBERG / KARL WEIGL Verklärte Nacht Works for Piano Trio Osiris Trio 1 ARNOLD SCHÖNBERG / KARL WEIGL Verklärte Nacht Works for Piano Trio Osiris Trio Ellen Corver piano Peter Brunt violin Larissa Groeneveld cello ARNOLD SCHÖNBERG (1874-1951) In September 1899, Arnold history. Schönberg’s starting point [1] Verklärte Nacht op. 4 (1899) 31:46 Schönberg was on vacation in the was one of the poems from Dehmel’s Arranged for piano trio by Eduard Steuermann Austrian village of Payerbach am Weib und Welt cycle, which raised Semmering with his friend, Alexander a furore following its publication in KARL WEIGL (1881-1949) von Zemlinsky, and Alexander’s sister 1896: conservative critics found the Piano Trio (1938-39) Mathilde. Schönberg was head over poems to be erotic, immoral and even [2] Allegro moderato 9:47 heels in love with Mathilde (they blasphemous. [3] Andante 8:27 were married 2 years later) and had [4] Allegro molto 5:09 also fallen completely under the Schönberg had already composed spell of the work of the German poet some songs to poems by Dehmel in Richard Dehmel – famous but at 1897, but it was not until 1899 – his total time 55:10 the same time highly controversial, ‘Dehmel year’ – that he felt fully up fêted by some and vilified by others. to the task of setting the violent Schönberg’s own development as emotions of this poetry to music in a a composer was rapid indeed, as convincing way: as well as Verklärte he successfully transformed the Nacht, he set about working on eight influences of Brahms and Wagner songs based on Dehmel’s poems. -

Mahler's Klagende Lied

Mahler’s Klagende Lied SIMONE YOUNG’S VISIONS OF VIENNA 4 – 7 DECEMBER SYDNEY OPERA HOUSE CONCERT DIARY FEBRUARY 2020 The 1950s Latin Lounge Wed 5 Feb, 7pm Thu 6 Feb, 7pm Program includes: Sat 8 Feb, 7pm GERSHWIN Cuban Overture Sydney Town Hall MARQUEZ Danzón No.2 BERNSTEIN West Side Story – Mambo Guy Noble conductor Imogen Kelly dancer Ali McGregor soprano The Rite of Spring Symphony Hour Wed 19 Feb, 7pm RIOT AT THE BALLET Thu 20 Feb, 7pm WAGNER Die Meistersinger – Prelude Sydney Town Hall STRAVINSKY The Rite of Spring Pietari Inkinen conductor Abercrombie & Kent Debussy and Ravel Masters Series THE GREAT IMPRESSIONISTS Wed 26 Feb, 8pm RAVEL Piano Concerto in G Fri 28 Feb, 8pm MENDELSSOHN The Hebrides Sat 29 Feb, 8pm DEBUSSY La mer Thursday Afternoon Symphony Jun Märkl conductor Thu 27 Feb, 1.30pm Alexandra Dariescu piano Great Classics Sat 29 Feb, 2pm Sydney Town Hall MARCH 2020 Ben Folds Sydney Symphony Presents Fri 6 Mar, 8pm THE SYMPHONIC TOUR Sat 7 Mar, 8pm Pop icon and music innovator Ben Folds Sydney Town Hall returns to Sydney following his last sold- out shows with the Sydney Symphony. Ben Folds Nicholas Buc conductor Scheherazade Symphony Hour Wed 11 Mar, 7pm HYPNOTIC AND SUBLIME Thu 12 Mar, 7pm DEBUSSY Prelude to the Afternoon of a Faun Tea & Symphony RIMSKY-KORSAKOV Scheherazade Fri 13 Mar, 11am Alexander Shelley conductor Sydney Town Hall Debussy, Mozart and Rimsky-Korsakov Emirates Metro Series Fri 13 Mar, 8pm SENSE AND SENSUALITY Sydney Town Hall DEBUSSY Prelude to the Afternoon of a Faun MOZART Sinfonia Concertante, K.364 RIMSKY-KORSAKOV Scheherazade Alexander Shelley conductor Harry Bennetts violin Tobias Breider viola Abercrombie & Kent Beethoven Missa Solemnis Masters Series MUSIC OF INSPIRATION Wed 18 Mar, 8pm BEETHOVEN Missa Solemnis Fri 20 Mar, 8pm Sat 21 Mar, 8pm Donald Runnicles conductor Siobhan Stagg soprano Sydney Town Hall Vasilisa Berzhanskaya mezzo-soprano Samuel Sakker tenor Derek Welton bass Sydney Philharmonia Choirs Cats 240x150.indd 1 2/9/19 16:40 WELCOME Welcome to the Abercrombie & Kent Masters Series. -

Program Book

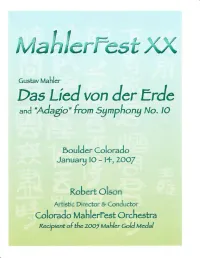

I e lson rti ic ire r & ndu r Schedule of Events CHAMBER CONCERTS Wednesday, January 1.O, 2007, 7100 PM Boulder Public Library Canyon Theater,9th & Canyon Friday, January L3, 7 3O PM Rocky Mountain Center for Musical Arts, 200 E. Baseline Rd., Lafayette Program: Songs on Chinese andJapanese Poems SYMPOSIUM Saturday, January L7, 2OO7 ATLAS Room 100, University of Colorado-Boulder 9:00 AM - 4:30 PM 9:00 AM: Robert Olson, MahlerFest Conductor & Artistic Director 10:00 AM: Evelyn Nikkels, Dutch Mahler Society 11:00 AMrJason Starr, Filmmaker, New York City Lunch 1:00 PM: Stephen E Heffiing, Case Western Reserve University, Keynote Speaker 2100 PM: Marilyn McCoy, Newburyport, MS 3:00 PMr Steven Bruns, University of Colorado-Boulder 4:00 PM: Chris Mohr, Denver, Colorado SYMPHONY CONCERTS Saturday, January L3' 2007 Sunday,Janaary L4,2O07 Macky Auditorium, CU Campus, Boulder Thomas Hampson, baritone Jon Garrison, tenor The Colorado MahlerFest Orchestra, Robert Olson, conductor See page 2 for details. Fundingfor MablerFest XXbas been Ttrouid'ed in ltartby grantsftom: The Boulder Arts Commission, an agency of the Boulder City Council The Scienrific and Culrural Facilities Discrict, Tier III, administered by the Boulder County Commissioners The Dietrich Foundation of Philadelphia The Boulder Library Foundation rh e va n u n dati o n "# I:I,:r# and many music lovers from the Boulder area and also from many states and countries [)AII-..]' CAMEI{\ il M ULIEN The ACADEMY Twent! Years and Still Going Strong It is almost impossible to fully comprehend -

Pdf 139.3 Kb

Dresdner Philharmonie The Dresden Philharmonic can look back on 150 years of history as the orchestra of Saxony’s capital Dresden. When the so-called “Gewerbehaussaal” opened on 29 November 1870, the citizens of the city were given the opportunity to organise major orchestra concerts. Philharmonic concerts were held regularly starting in 1885; the orchestra adopted its present name in 1923. In its first decades, composers such as Brahms, Tchaikovsky, Dvořák and Strauss conducted the Dresdner Philharmonie with their own works. The first desks were presided over by outstanding concertmasters such as Stefan Frenkel, Simon Goldberg and the cellists Stefan Auber and Enrico Mainardi. From 1934, Carl Schuricht and Paul van Kempen led the orchestra; van Kempen in particular guided the Dresden Philharmonic to top achievements. All of Bruckner’s symphonies were first performed in their original versions, which earned the orchestra the reputation of a “Bruckner orchestra” and brought renowned guest conductors such as Hermann Abendroth, Eduard van Beinum, Fritz Busch, Eugen Jochum, Joseph Keilbert, Erich Kleiber, Hans Knappertsbusch and Franz Konwitschny to the rostrum. After 1945 and into the 1990s, Heinz Bongartz, Horst Förster, Kurt Masur (from 1994 also honorary conductor), Günther Herbig, Herbert Kegel, Jörg-Peter Weigle and Michel Plasson were the principal conductors. In recent years, conductors such as Marek Janowski, Rafael Frühbeck de Burgos and Michael Sanderling have shaped the orchestra. As of season 2019/2020, Marek Janowski has returned to the Dresden Philharmonic as principal conductor and artistic director. Its home is the highly modern concert hall inaugurated in April 2017 in the Kulturpalast building in the heart of the historic old town.