Quick Facts – the Pork Industry at a Glance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pork Q&A Answer

Supplemental Activity: TEACHER GUIDE Pork Q&A Answer Key Pork Q & A - ANSWER KEY Cooking Methods 1. How does the tenderness of the meat determine the method of cooking (direct or indirect heat)? As a general rule, the cuts from the loin and tenderloin tend to be the most tender – cook with direct heat. When working with larger, less-tender cuts, simply remember to cook slowly over indirect heat. 2. What is sautéing? What cuts of meat are ideal for sautéing? • Sauteing is to add a little cooking oil to pan; sauté over medium-high heat and turn once halfway through cooking time. • Meat cuts to sauté include cutlets, loin chops (bone-in or boneless), tenderloin medallions, and ground pork patties. 3. What is grilling? What cuts of meat are ideal for grilling? • Grilling is a high-heat, direct method of cooking meat over live flames. • Meat cuts to grill include loin chops (3/4 inch thickness), thick loin chops (1½ inch thick and boneless), loin kabobs, tenderloin, and ground pork patties. 4. What does it mean to marinate? What are two cuts of pork to marinate? • To marinate means to let food stand in marinade for a certain length of time to tenderize it and develop its flavor. A marinade may be a flavorful liquid such as barbecue sauce or a dry rub. • Two cuts of pork to marinate could be pork shoulder and roasts. 5. What is another name for indirect grilling? Barbecuing 6. What is barbecuing? What cuts of pork are best for barbecuing? Barbecuing is characterized by a long, low-heat, smoke-cooking method using coals, smoldering logs or chunks of wood. -

County of Emmet

County of Emmet Planning, Zoning & Construction Resources 3434 Harbor-Petoskey Rd Ste E Harbor Springs, Michigan 49740 Phone: 231-348-1735 www.emmetcounty.org Fax: 231-439-8933 EMMET COUNTY BUILDING INSPECTION DEPARTMENT PLAN REVIEW COMPLIANCE LIST 2009 MICHIGAN BUILDING CODE [Date] [Job Number] [Owner's Last Name], [Type of Improvement], [Building Use] [Job Site Address], [Jurisdiction] This work is being reviewed under the provisions of the Michigan Building Code. A copy of the plans submitted and approved by the Emmet County Building Inspection Department will be returned to the applicant and are to remain at the job site during construction. The plans have been reviewed for compliance with Michigan's barrier free design requirements as they may be applicable. This department has no authority over the federal standards contained in the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990, 42 U.S.C. 12204. These federal standards may have provisions that apply to your project that should be considered. The building is classified as [identify use group(s)]. The mixed use groups are reviewed as [separated or non-separated] uses. A fire wall with a [identify the hourly rating] rating [indicate the location of the fire wall] is used to create separate buildings. The building height is [identify height(s) in stories and feet]. The building area is [identify the building area(s)]. The permitted open space area increase is [identify the permitted open space area increase(s)]. The sprinkler height increase is [identify the sprinkler height increase]. The permitted sprinkler area increase is [identify the sprinkler area increase]. The minimum type of construction is [identify the type of construction]. -

Title: Survey of Microbiological Status of Offal Products from Pork

Title: Survey of Microbiological Status of Offal Products from Pork Processing Facilities in the United States – NPB #16-162 Institution: South Dakota State University. Investigators: Alan Erickson (Principal Investigator), South Dakota State University; William Benjy Mikel, WPF Technical Services; Laura Ruesch SDSU; Jane Christopher-Hennings, SDSU; Monte Fuhrman, Pipestone Veterinary Services; Jonathan Ertl, Sioux Nation Ag Center. Date submitted: 10/31/17 Industry Summary: In the United States, approximately five million metric tons of pork variety meats and other byproducts are generated each year with a large amount of this material being rendered to generate low value products like pet food, meat/bone meal, fat, and grease. An alternative use of the US variety meats would be to market and sell them to consumers in countries like China that prefer strong tasting pork products like the variety meats. The desirability of these products in foreign markets makes them higher value products, which could help increase the value of live hogs for US producers. To be able to market and sell these variety meats in global markets, it is important to understand the microbiological status of these products. Therefore, the objective of the current study was to: Determine the microbiological profile of commonly consumed offal products (liver, heart, kidney, brain and intestine) as currently handled in pork production facilities in the United States. This microbiological profile will include tests for: mesophilic aerobic plate counts (APC), Salmonella, Yersinia enterocolitica, and Toxoplasma gondii. To address this objective, samples of heart, kidney, liver, brain and intestine were obtained from 15 pork processing plants in 10 states found across the Midwestern and Southeastern pork-producing region of the US. -

Sexism in the City “We're Simply Buying Too Much”

SEPTEMBER 2016 Japan’s number one English language magazine Five style-defining brands that are reinventing tradition SEXISM IN THE CITY Will men and women ever be equal in Japan’s workforce? “WE’RE SIMPLY BUYING TOO MUCH” Change the way you shop PLUS: The Plight of the Phantom Pig, Healthy Ice Cream, The Beauties of Akita, Q&A with Paralympics Athlete Saki Takakuwa 36 20 24 30 SEPTEMBER 2016 radar in-depth guide THIS MONTH’S HEAD TURNERS COFFEE-BREAK READS CULTURE ROUNDUP 8 AREA GUIDE: SENDAGAYA 19 SEXISM IN THE CITY 41 THE ART WORLD Where to eat, drink, shop, relax, and climb Will men and women ever be equal This month’s must-see exhibitions, including a miniature Mt. Fuji in Japan’s workforce? a “Dialogue with Trees,” and “a riotous party” at the Hara Museum. 10 STYLE 24 “WE’RE SIMPLY BUYING TOO MUCH” Bridge the gap between summer and fall Rika Sueyoshi explains why it’s essential 43 BOOKS with transitional pieces including one very that we start to change the way we shop See Tokyo through the eyes – and beautiful on-trend wrap skirt illustrations – of a teenager 26 THE PLIGHT OF THE PHANTOM PIG 12 BEAUTY Meet the couple fighting to save Okinawa’s 44 AGENDA We round up the season’s latest nail colors, rare and precious Agu breed Take in some theatrical Japanese dance, eat all featuring a little shimmer for a touch of the hottest food, and enter an “Edo-quarium” glittery glamor 28 GREAT LEAPS We chat with long jumper Saki Takakuwa 46 PEOPLE, PARTIES, PLACES 14 TRENDS as she prepares for the 2016 Paralympics Hanging out with Cyndi Lauper, Usain Bolt, If you can’t live without ice cream but you’re and other luminaries trying to eat healthier, then you’ll love these 30 COVER FEATURE: YUKATA & KIMONO vegan and fruity options. -

Vegetarianism and World Peace and Justice

Visit the Triangle-Wide calendar of peace events, www.trianglevegsociety.org/peacecalendar VVeeggeettaarriiaanniissmm,, WWoorrlldd PPeeaaccee,, aanndd JJuussttiiccee By moving toward vegetarianism, can we help avoid some of the reasons for fighting? We find ourselves in a world of conflict and war. Why do people fight? Some conflict is driven by a desire to impose a value system, some by intolerance, and some by pure greed and quest for power. The struggle to obtain resources to support life is another important source of conflict; all creatures have a drive to live and sustain themselves. In 1980, Richard J. Barnet, director of the Institute for Policy Studies, warned that by the end of the 20th century, anger and despair of hungry people could lead to terrorist acts and economic class war [Staten Island Advance, Susan Fogy, July 14, 1980, p.1]. Developed nations are the largest polluters in the world; according to Mother Jones (March/April 1997, http://www. motherjones.com/mother_jones/MA97/hawken2.html), for example, Americans, “have the largest material requirements in the world ... each directly or indirectly [using] an average of 125 pounds of material every day ... Americans waste more than 1 million pounds per person per year ... less than 5 percent of the total waste ... gets recycled”. In the US, we make up 6% of the world's population, but consume 30% of its resources [http://www.enough.org.uk/enough02.htm]. Relatively affluent countries are 15% of the world’s population, but consume 73% of the world’s output, while 78% of the world, in developing nations, consume 16% of the output [The New Field Guide to the U. -

Breeds of Swine

Breeds of Swine *Eight major breeds of swine produced in the US. *Dark breeds or terminal breeds are used for their production abilities such as meatiness, leanness, durability, growth rate, and feed efficiency. *White breeds or maternal breeds are used for their reproductive abilities such as mothering ability, litter size, and milking ability. Breeds of Swine Dark/Terminal Breeds White/Maternal Breeds Berkshire Chester White Duroc Landrace Hampshire Yorkshire Poland China Spot Berkshire Duroc Hampshire Poland China Spot Chester White Landrace Yorkshire Sex Classes of Swine *Gilt – Any female pig that has not yet given birth. *Sow – A female pig that has given birth. *Boar – An intact male hog kept only for breeding purposes. *Barrow – A castrated male hog used for meat. Scientific Classification of Swine Phylum: Chordata Subphylum: Vertebrata Class: Mammalia Order: Artiodactyla Suborder: Suina Family: Suidae Genus: Sus Species: domesticus Top Ten Swine Producing States 1. Iowa 6. Nebraska 2. North Carolina 7. Missouri 3. Minnesota 8. Oklahoma 4. Illinois 9. Kansas 5. Indiana 10. Ohio Top Five Swine Producing Countries 1. China 2. European Union 3. United States 4. Brazil 5. Canada Pig Vital Signs Normal Body Temperature 101-103°F Normal Heart Rate 60-80 beats/minute Normal Respiration Rate 30-40 breaths/minute Important Breeding Numbers Litter Size: 7-15 pigs Birth Weight: 2-3.5 lbs Weaned at: 21 days Sexual Maturity: 6-8 months # Ideal Number of Teats: 7 per side Estrous Cycle: 21 days (range of 19-21) # Duration of Estrus (heat): 2-3 days Gestation: 114 days (3 months, 3 weeks, 3 days) (range of 112-115) Important Weights of Hogs Birth Weight: 2-3.5 lbs Wean Weight: 15 lbs at 21 days Slaughter Weight: 250 lbs Mature Weight: Male 500-800 lbs Female 400-700 lbs Ear Notching System Right Ear Left Ear Litter Number Individual Pig Number *No more than 2 notches per area except for 81, only one notch. -

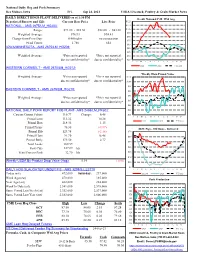

National Daily Hog and Pork Summary

National Daily Hog and Pork Summary Des Moines, Iowa Fri, Sep 24, 2021 USDA Livestock, Poultry & Grain Market News DAILY DIRECT HOGS PLANT DELIVERED as of 1:30 PM Weekly National P.M. Wtd Avg Negotiated Barrow and Gilt: Carcass Base Price Live Price $125 NATIONAL - AMS 2675/LM_HG203: $115 Range: $73.00 - $85.50 $52.00 - $61.00 $105 Weighted Average: $76.93 $58.43 $95 $85 Change from Prior Day: 0.40 higher no comparison $75 Head Count: 2,780 654 $65 IOWA/MINNESOTA - AMS 2675/LM_HG206: $55 $45 Weighted Average: *Price not reported *Price not reported $35 due to confidentiality* due to confidentiality* $25 J F M A M J J A S O N D 2021 2020 5 Yr Avg WESTERN CORNBELT - AMS 2675/LM_HG212: Weekly Ham Primal Value Weighted Average: *Price not reported *Price not reported $110 due to confidentiality* due to confidentiality* $100 $90 EASTERN CORNBELT - AMS 2675/LM_HG210: $80 $70 Weighted Average: *Price not reported *Price not reported due to confidentiality* due to confidentiality* $60 $50 NATIONAL DAILY PORK REPORT FOB PLANT- AMS 2498/LM_PK602: $40 Carcass Cutout Values 110.77 Change: 6.48 $30 J F M A M J J A S O N D Primal Loin 113.32 10.28 2021 2020 5 Yr Avg Primal Butt 114.36 1.15 Primal Picnic 76.36 (-4.87) SEW Pigs - 10# Basis - Delivered Primal Rib 129.78 (-2.16) $70 Primal Ham 91.70 16.48 $60 Primal Belly 179.50 2.77 $50 Total Loads 360.59 Pork Cuts 327.89 lds. -

Uniform Retail Meat Identity Standards a PROGRAM for the RETAIL MEAT INDUSTRY APPROVED NAMES PORK

Uniform Retail Meat Identity Standards A PROGRAM FOR THE RETAIL MEAT INDUSTRY APPROVED NAMES PORK This section is organized in the following order: SELECT AN AREA TO VIEW IT Species Cuts Chart LARGER SEE THE Species-Specific FOLLOWING Primal Information AREAS Index of Cuts Cut Nomenclature PORK -- Increasing in and U.P.C.Numbers Popularity Figure 1-- Primal (Wholesale) Cuts and Bone Structure of Pork Figure 2 -- Loin Roasts -- Center Chops INTRODUCTION Figure 3 -- Portion Pieces APPROVED NAMES -- Center Chops BEEF Figure 4-- Whole or Half Loins VEAL PORK Figure 5 -- Center Loin or Strip Loin LAMB GROUND MEATS Pork Belly EFFECTIVE MEATCASE MANAGEMENT & Pork Leg FOOD SAFETY MEAT COOKERY Pork Cuts GLOSSARY & REFERENCES Approved by the National Pork Board INDUSTRY-WIDE COOPERATIVE MEAT IDENTIFICATION STANDARDS COMMITTEE Uniform Retail Meat Identity Standards A PROGRAM FOR THE RETAIL MEAT INDUSTRY APPROVED NAMES PORK INTRODUCTION APPROVED NAMES BEEF VEAL PORK LAMB GROUND MEATS EFFECTIVE MEATCASE MANAGEMENT FOOD SAFETY MEAT COOKERY GLOSSARY & REFERENCES INDUSTRY-WIDE COOPERATIVE MEAT IDENTIFICATION STANDARDS COMMITTEE Uniform Retail Meat Identity Standards A PROGRAM FOR THE RETAIL MEAT INDUSTRY APPROVED NAMES PORK INTRODUCTION APPROVED NAMES BEEF VEAL PORK LAMB GROUND MEATS EFFECTIVE MEATCASE MANAGEMENT FOOD SAFETY MEAT COOKERY GLOSSARY & REFERENCES INDUSTRY-WIDE COOPERATIVE MEAT IDENTIFICATION STANDARDS COMMITTEE Uniform Retail Meat Identity Standards A PROGRAM FOR THE RETAIL MEAT INDUSTRY APPROVED NAMES PORK INTRODUCTION APPROVED NAMES BEEF -

The History of Florida's State Flag the History of Florida's State Flag Robert M

Nova Law Review Volume 18, Issue 2 1994 Article 11 The History of Florida’s State Flag Robert M. Jarvis∗ ∗ Copyright c 1994 by the authors. Nova Law Review is produced by The Berkeley Electronic Press (bepress). https://nsuworks.nova.edu/nlr Jarvis: The History of Florida's State Flag The History of Florida's State Flag Robert M. Jarvis* TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION ........ .................. 1037 II. EUROPEAN DISCOVERY AND CONQUEST ........... 1038 III. AMERICAN ACQUISITION AND STATEHOOD ......... 1045 IV. THE CIVIL WAR .......................... 1051 V. RECONSTRUCTION AND THE END OF THE NINETEENTH CENTURY ..................... 1056 VI. THE TWENTIETH CENTURY ................... 1059 VII. CONCLUSION ............................ 1063 I. INTRODUCTION The Florida Constitution requires the state to have an official flag, and places responsibility for its design on the State Legislature.' Prior to 1900, a number of different flags served as the state's banner. Since 1900, however, the flag has consisted of a white field,2 a red saltire,3 and the * Professor of Law, Nova University. B.A., Northwestern University; J.D., University of Pennsylvania; LL.M., New York University. 1. "The design of the great seal and flag of the state shall be prescribed by law." FLA. CONST. art. If, § 4. Although the constitution mentions only a seal and a flag, the Florida Legislature has designated many other state symbols, including: a state flower (the orange blossom - adopted in 1909); bird (mockingbird - 1927); song ("Old Folks Home" - 1935); tree (sabal palm - 1.953); beverage (orange juice - 1967); shell (horse conch - 1969); gem (moonstone - 1970); marine mammal (manatee - 1975); saltwater mammal (dolphin - 1975); freshwater fish (largemouth bass - 1975); saltwater fish (Atlantic sailfish - 1975); stone (agatized coral - 1979); reptile (alligator - 1987); animal (panther - 1982); soil (Mayakka Fine Sand - 1989); and wildflower (coreopsis - 1991). -

Read Our Fact Sheet on the PIGS

Factsheet The PIGS Act Ending the use of extreme confinement of mother pigs What Does the Pigs in Gestation Stalls (PIGS) Act Do? This bill would ban the use of gestation stalls (also known as “crates”) for housing pregnant pigs and require that they have at least 36 square feet of space and the ability to lie down, stand up, and turn around freely. The two-foot by seven-foot crates currently used in the industry are so restrictive that pregnant pigs are essentially immobilized – sadly, they spend most of their lives kept in these horrific conditions. By forbidding this extreme form of confinement, Congress will level the playing field for all producers (nearly a dozen states restrict the practice and dozens of retailers have pledged to buy pork only from crate-free operations) and give consumers more confidence about the pig industry’s animal welfare standards. Why Support the PIGS Act? Keeping Pregnant Pigs in Extreme Confinement is Inhumane A breeding pig may spend up to three years intensively confined in a crate, and that’s the bulk of her entire lifespan. A pig can weigh 400 pounds, and the two-foot wide crate immobilizes her for months on end. The Humane Methods of Slaughter Act stipulates that pigs must be rendered insensible to pain prior to slaughter, and it only makes sense to have humane treatment standards for these animals for the duration of their lives. Pigs raised for meat are not kept in these needlessly restrictive crates, and neither should pregnant pigs. Major Retailers are Moving Away from Extreme Confinement Almost every major food retailer in the United States – from McDonald’s to Costco to Aramark – has agreed to phase out all purchasing of pork from farms that confine sows in gestation crates, with most policies taking effect in 2022. -

4-H Pork Production Manual

4-H PORK PRODUCTION MANUAL This publication, the record sheet and other sheets all are intended to help the 4-H member succeed in the 4-H Swine Project. The best way to learn is by doing -- especially by working with your family, your 4-H swine project leader, other 4-H swine project members, and your local swine producers and Cooperative Extension Agents. In the process of managing your project, you will also be completing an educational goal. It is important to learn to take the responsibility that goes with managing your project. The New York State Swine programs consist of the Empire Market Hog program, the breeding program and a variety of educational and competitive activities. All 4-H swine projects can be completed at county level and at the New York State Fair. Members wishing to enroll in any of these activities should notify their County Cooperative Extension 4-H agent of their interest. A variety of educational materials will then be supplied. The Empire Market Hog Contest will be conducted during the New York State Fair as a part of the 4-H Swine Show. Members may enter either the “A” Division or the “B” Division. Each division is further divided into junior and senior sections. “A” Division contestants must have at least one market hog that can be entered in the State 4-H Market Swine Show at the correct market weight. “B“ Division contestants are not required to show, but are required to bring accurate records to be evaluated. Each contestant will be expected to: 1. -

Ham and Food Safety

United States Department of Agriculture Food Safety and Inspection Service Food Safety Information PhotoDisc Ham and Food Safety ams: They can be fresh, cook-before-eating, cooked, picnic, and country types. There are so many kinds, Hand their storage times and cooking times vary. This background information serves to carve up the facts and make them easier to understand. Definition Hams may be fresh, cured, or cured-and-smoked. Ham is the cured leg of pork. Fresh ham is an uncured leg of pork. Fresh ham will bear the term “fresh” as part of the product name and is an indication that the product is not cured. “Turkey” ham is a ready-to-eat product made from cured thigh meat of turkey. The term “turkey ham” is always followed by the statement “cured turkey thigh meat.” The usual color for cured ham is deep rose or pink; fresh ham (which is not cured) has the pale pink or beige color of a fresh pork roast; country hams and prosciutto (which are dry cured) range from pink to a mahogany color. Hams are either ready to eat or not. Ready-to-eat hams include prosciutto and cooked hams; they can be eaten right out of the package. Fresh hams and hams that are only treated to destroy trichinae (which may include heating, freezing, or curing in the plant) must be cooked by the consumer before eating. Hams that must be cooked will bear cooking instructions and safe handling instructions. Hams that are not ready-to-eat, but have the appearance of ready-to-eat products, will bear a prominent statement on the principal display panel (label) indicating the product needs cooking, e.g., “cook thoroughly.” In addition, the label must bear cooking directions.