The Reception of the Chansons De Geste

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE HISTORY of ORLANDO FURIOSO

ElizabethanDrama.org presents the Annotated Popular Edition of THE HISTORY of ORLANDO FURIOSO By Robert Greene Written c. 1590 Earliest Extant Edition: 1594 Featuring complete and easy-to-read annotations. Annotations and notes © Copyright Peter Lukacs and ElizabethanDrama.org, 2020. This annotated play may be freely copied and distributed. THE HISTORY OF ORLANDO FURIOSO BY ROBERT GREENE Written c. 1590 Earliest Extant Edition: 1594 DRAMATIS PERSONÆ. INTRODUCTION to the PLAY Marsilius, Emperor of Africa Robert Greene's Orlando Furioso is a brisk play that Angelica, Daughter to Marsilius. is very loosely based on the great Italian epic poem of the Soldan of Egypt. same name. The storyline makes little logical sense, but Rodomont, King of Cuba. lovers of Elizabethan language will find the play to be enter- Mandricard, King of Mexico. taining, if insubstantial, reading. The highlights of Orlando Brandimart, King of the Isles. Furioso are comprised primarily of the comic scenes of Sacripant, a Count. the hero and knight Orlando, who has gone mad after losing Sacripant's Man. his love, the princess Angelica, interacting with local rustics, Orlando, a French Peer. who in the fashion of the age are, though ostensibly inter- Orgalio, Page to Orlando. national, thoroughly English. Though never to be confused Medor, Friend to Angelica. with the greatest works of the age, Greene's Orlando de- serves to be read, and perhaps even occasionally staged. French Peers: Ogier. OUR PLAY'S SOURCE Namus. Oliver. The text of this play was originally adapted from the Turpin. 1876 edition of Greene's plays edited by Alexander Dyce, Several other of the Twelve Peers of France, whose but was then carefully compared to the original 1594 quarto. -

© in This Web Service Cambridge University

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-04278-0 - Romance And History: Imagining Time from the Medieval to the Early Modern Period Edited by Jon Whitman Index More information Index A note is normally indexed only if the topic for which it is cited is not specified in the corresponding discussion in the body of the text. Abelard, Peter, 64 193–4, 196, 200–2, 204–5, 211, 249, Achilles Tatius, 200 281 (n34), 293 (n11), 294 (n21), Adémar de Chabannes, 143 302 (n18) Aeneas, 9–10, 26, 29–30, 44, 80–1, 130, 140, Aristotle, 165, 171, 176, 181, 195, 198, 201–2, 225 154–5, 188, 199, 202–3, 209, 219, Poetics, 17, 151, 183, 190–4, 204 296 (n27) Armida, 18, 198, 204 see also Eneas; Roman d’Eneas; Virgil artfulness, 9, 26–31, 34–8, 55, 67, 226, 252 Alamanni, Luigi, Girone il Cortese, 291 (n12) see also ingenium/engin/ingenuity Albanactus, 154 Arthur, 10, 13, 56–73, 75–9, 83, 105–33, 141, Alexander the Great, 9–10, 23–7, 32–8, 44, 101, 150, 156, 158, 160, 166, 197, 220, 225, 103, 222–3 247–9 Alfonso I d’Este, 152 see also Arthurian romance; “matters” of Alfred the Great, 107 narrative, Britain allegory, 18, 31, 206–8, 217–18, 221, 225, 234, Arthur, son of Henry VII (Arthur Tudor), 109, 295 (n22) 123 Alliterative Morte Arthure, 13, 105, 107, 110–19, Arthurian romance, 3, 5–6, 11, 14–17, 47, 90–104, 248 145, 149–50, 158–62, 169–78, 181, 188, 197, Amadis de Gaula/Garci Rodríguez de Montalvo, 224, 229, 247–9 16, 124, 169, 175–9, 228–30 see also Arthur; “matters” of narrative, Britain Ami et Amile, 279 (n2) Ascham, Roger, 123 Amyot, Jacques, 191–2 Aspremont, -

Emanuel J. Mickel Ganelon After Oxford the Conflict Between Roland

Emanuel J. Mickel Ganelon After Oxford The conflict between Roland and Ganelon and the subsequent trial form an important part of the Chanson de Roland. How one looks at the trial and Ganelon's role in the text bears significantly on one's interpretation of the epic. While most critics acknowledge that Roland is the hero of the chanson and Ganelon the traitor, many, perhaps a majority, find flaws in Roland's character or conduct and accept the argument that Ganelon had some justification for his actions in the eyes of Charlemagne's barons and, perhaps, in the view of the medieval audience. Roland, of course, is blamed for desmesure and Ganelon is justified by the argument that his open defiance of Roland and the peers in the council scene gave him the right, according to the ancient Germanic ethical and legal code, to take vengeance on his declared adversaries. Proponents of this thesis allege that the Chanson de Roland, a text which they date to the eleventh century, reflects a growing tension and conflict between the powerful feudal barons and the growing power of the monarchy.1 The barons represent the traditions and custom law of a decentralized state where the king is primus inter pares, but essentially a baron like themselves. As the French monarchy grew in strength and was bolstered in a theoretical sense by the centralizing themes of Roman law, conflict between the crown and the nobility became apparent.2 1 For specific analysis of the trial in terms of allegedly older Germanic tradition, see Ruggero Ruggieri, Il Processo di Gano nella Chanson de Roland (Firenze: Sansoni, 1936); also George F. -

14 Pierrepont at a Crossroads of Literatures

14 Pierrepont at a crossroads of literatures An instructive parallel between the first branch of the Karlamagnús Saga, the Dutch Renout and the Dutch Flovent Abstract: In the French original of the first branch of the Karlamagnús Saga [= fKMSI], in the Dutch Renout and in the Dutch Flovent – three early 13th century texts from present-day Bel- gium – a toponym Pierrepont plays a conspicous part (absent, however, from the French models of Renout and Flovent); fKMSI and Renout even have in common a triangle ‘Aimon, vassal of Charlemagne – Aie, his wife – Pierrepont, their residence’. The toponym is shown to mean Pierrepont (Aisne) near Laon in all three texts. In fKMSI, it is due almost certainly to the intervention of one of two Bishops of Liège (1200−1238) from the Pierrepont family, and in the other two texts to a similar cause. Consequently, for fKMSI a date ‘before 1240’ is proposed. According to van den Berg,1 the Middle Dutch Flovent, of which only two frag- ments are preserved,2 was probably written by a Fleming (through copied by a Brabantian) and can very roughly be dated ‘around 1200’ on the basis of its verse technique and syntax. In this text, Pierrepont plays a conspicuous part without appearing in the French original.3 In the first fragment, we learn that King Clovis is being besieged in Laon by a huge pagan army (vv. 190 ss.). To protect their rear, the pagans build a castle at a distance of four [presumably French] miles [~18 km] from Laon. Its name will be Pierlepont (vv. -

Jonesexcerpt.Pdf

2 The Texts—An Overview N’ot que trois gestes en France la garnie; ne cuit que ja nus de ce me desdie. Des rois de France est la plus seignorie, et l’autre aprés, bien est droiz que jeu die, fu de Doon a la barbe florie, cil de Maience qui molt ot baronnie. De ce lingnaje, ou tant ot de boidie, fu Ganelon, qui, par sa tricherie, en grant dolor mist France la garnie. La tierce geste, qui molt fist a prisier, fu de Garin de Monglenne au vis fier. Einz roi de France ne vodrent jor boisier; lor droit seignor se penerent d’aidier, . Crestïenté firent molt essaucier. [There were only threegestes in wealthy France; I don’t think any- one would ever contradict me on this. The most illustrious is the geste of the kings of France; and the next, it is right for me to say, was the geste of white-beardedPROOF Doon de Mayence. To this lineage, which was full of disloyalty, belonged Ganelon, who, by his duplic- ity, plunged France into great distress. The thirdgeste , remarkably worthy, was of the fierce Garin de Monglane. Those of his lineage never once sought to deceive the king of France; they strove to help their rightful lord, . and they advanced Christianity.] Bertrand de Bar-sur-Aube, Girart de Vienne Since the Middle Ages, the corpus of chansons de geste has been di- vided into groups based on various criteria. In the above prologue to the thirteenth-century Girart de Vienne, Bertrand de Bar-sur-Aube classifies An Introduction to the Chansons de Geste by Catherine M. -

1 the Middle Ages

THE MIDDLE AGES 1 1 The Middle Ages Introduction The Middle Ages lasted a thousand years, from the break-up of the Roman Empire in the fifth century to the end of the fifteenth, when there was an awareness that a ‘dark time’ (Rabelais dismissively called it ‘gothic’) separated the present from the classical world. During this medium aevum or ‘Middle Age’, situated between classical antiquity and modern times, the centre of the world moved north as the civil- ization of the Mediterranean joined forces with the vigorous culture of temperate Europe. Rather than an Age, however, it is more appropriate to speak of Ages, for surges of decay and renewal over ten centuries redrew the political, social and cultural map of Europe, by war, marriage and treaty. By the sixth century, Christianity was replacing older gods and the organized fabric of the Roman Empire had been eroded and trading patterns disrupted. Although the Church kept administrative structures and learning alive, barbarian encroachments from the north and Saracen invasions from the south posed a continuing threat. The work of undoing the fragmentation of Rome’s imperial domain was undertaken by Charlemagne (742–814), who created a Holy Roman Empire, and subsequently by his successors over many centuries who, in bursts of military and administrative activity, bought, earned or coerced the loyalty of the rulers of the many duchies and comtés which formed the patchwork of feudal territories that was France. This process of centralization proceeded at variable speeds. After the break-up of Charlemagne’s empire at the end of the tenth century, ‘France’ was a kingdom which occupied the region now known as 2 THE MIDDLE AGES the Île de France. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Marvelous Generations: Lancastrian Genealogies and Translation in Late Medieval and Early M

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Marvelous Generations: Lancastrian Genealogies and Translation in Late Medieval and Early Modern England and Iberia A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in English by Sara Victoria Torres 2014 © Copyright by Sara Victoria Torres 2014 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Marvelous Generations: Lancastrian Genealogies and Translation in Late Medieval and Early Modern England and Iberia by Sara Victoria Torres Doctor of Philosophy in English University of California, Los Angeles, 2014 Professor Christine Chism, Co-chair Professor Lowell Gallagher, Co-chair My dissertation, “Marvelous Generations: Lancastrian Genealogies and Translation in Late Medieval and Early Modern England and Iberia,” traces the legacy of dynastic internationalism in the fifteenth, sixteenth, and early-seventeenth centuries. I argue that the situated tactics of courtly literature use genealogical and geographical paradigms to redefine national sovereignty. Before the defeat of the Spanish Armada in 1588, before the divorce trials of Henry VIII and Catherine of Aragon in the 1530s, a rich and complex network of dynastic, economic, and political alliances existed between medieval England and the Iberian kingdoms. The marriages of John of Gaunt’s two daughters to the Castilian and Portuguese kings created a legacy of Anglo-Iberian cultural exchange ii that is evident in the literature and manuscript culture of both England and Iberia. Because England, Castile, and Portugal all saw the rise of new dynastic lines at the end of the fourteenth century, the subsequent literature produced at their courts is preoccupied with issues of genealogy, just rule, and political consent. Dynastic foundation narratives compensate for the uncertainties of succession by evoking the longue durée of national histories—of Trojan diaspora narratives, of Roman rule, of apostolic foundation—and situating them within universalizing historical modes. -

ROSALIND-The-Facts-T

THE PLAY “AS YOU LIKE IT” THE WOMAN ROSALIND THE FACTS WRITTEN: The year of 1599 was an especially busy year for Williams Shakespeare who wrote four plays for the Globe stage – “Much Ado About Nothing”, “Henry V”, “Julius Caesar” and “As You Like It”. PUBLISHED: The play was first published in the famous First Folio of 1923 AGE: The Bard was 35 years old when he wrote the play. (Born 1564-Died 1616) CHRONO: “As You Like It” holds the 21st position in the canon of 39 plays immediately after “Julius Caesar” and before “Hamlet” in 1601 GENRE: The play is most often joined with “The Two Gentlemen of Verona” and “The Comedy of Errors” to comprise the trio of “Early Comedies”. SOURCE: Shakespeare’s principal source was a prose pastoral romance, “Rosalynd”, published in 1590 by the English poet Thomas Lodge and “improved upon beyond measure” (Bloom); the two key characters of Touchstone and Jaques were Shakespeare’s memorable creations. TIMELINE: The action of the play covers a brief number of weeks allowing for the “to-ing & fro-ing” of getting from the Palace to the Forest. FIRST PERFORMANCE: The play’s first performance is uncertain although a performance at Wilton House – an English country house outside of London and the seat of the Earl of Pembroke – has been suggested as a possibility. The play’s popularity must surely have found its place in frequent Globe seasons but no records seem to attest to that fact. Page 2 “PASTORALS”: “There is a unique bucolic bliss that is conventional in pastorals, for it is common for people trapped in the hurly-burly of the crowded haunts of men to imagine wrongly that there is some delight in a simple life that existed in the ‘good old days’. -

Hero As Author in the Song of Roland

Hero as Author in The Song of Roland Brady Earnhart University of Virginia A modern reader with no experience in medieval literature who received the unlikely gift of a copy of The Song of Roland might be given pause by the title. Is it going to be a song about Roland? Written by Roland? Sung by him? A simple confusion, quickly cleared up, and yet perhaps providential in the more serious questions it leads us to: Are there ways in which the hero Roland resembles a poet? How might the oliphant function as the text's counterpart within the text itself, and who is the audience? What light could this approach shed on interpretive controversies? A comparison of Roland's situation and that of the writer of the epic is somewhat outside the critical fray, and need not attempt to trump more strictly ideological or linguistic examinations. At the same time, its own answers to commonly disputed critical questions may complement the answers other approaches have provided. It will be necessary first to clarify a few points that can no longer be taken for granted. I will be assuming, as most scholars do, that this work is based on an event that actually took place. I will be examining what I see as its departures from a less self-consciously artistic recording of the event, which seem to lean away from mimesis toward invention. Clearly, historical truth is chimerical, invention a matter of degree and subject to the intricacies of patronage and contemporary aesthetic decorum. One does not have to establish "exactly what happened," though, to examine the differences between earlier and later accounts of a battle, especially when the later account in question diverges so extravagantly and uniquely from the earlier ones. -

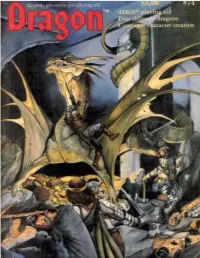

DRAGON Magazine (ISSN 0279-6848) Is Pub- the Occasion, and It Is Now So Noted

DRAGON 1 Publisher: Mike Cook Editor-in-Chid: Kim Mohan Quiet celebration Editorial staff: Marilyn Favaro Roger Raupp Birthdays dont hold as much meaning Patrick L. Price Vol. VII, No. 12 June 1983 for us any more as they did when we were Mary Kirchoff younger. That statement is true for just Office staff: Sharon Walton SPECIAL ATTRACTION about all of us, of just about any age, and Pam Maloney its true of this old magazine, too. Layout designer: Kristine L. Bartyzel June 1983 is the seventh anniversary of The DRAGON Magazine Contributing editors: Roger Moore Combat Computer . .40 Ed Greenwood the first issue of DRAGON Magazine. A playing aid that cant miss National advertising representative: In one way or another, we made a pretty Robert Dewey big thing of birthdays one through five c/o Robert LaBudde & Associates, Inc. if you have those issues, you know what I 2640 Golf Road mean. Birthday number six came and OTHER FEATURES Glenview IL 60025 Phone (312) 724-5860 went without quite as much fanfare, and Landragons . 12 now, for number seven, weve decided on Wingless wonders This issues contributing artists: a quiet celebration. (Maybe well have a Jim Holloway Phil Foglio few friends over to the cave, but thats The electrum dragon . .17 Timothy Truman Dave Trampier about it.) Roger Raupp Last of the metallic monsters? This is as good a place as any to note Seven swords . 18 DRAGON Magazine (ISSN 0279-6848) is pub- the occasion, and it is now so noted. Have Blades youll find bearable lished monthly for a subscription price of $24 per a quiet celebration of your own on our year by Dragon Publishing, a division of TSR behalf, if youve a mind to, and I hope Hobbies, Inc. -

La Chronique Du Pseudo-Turpin Et La Chanson De Roland In: Revue De L'occident Musulman Et De La Méditerranée, N°25, 1978

Paulette Duval La chronique du pseudo-Turpin et la Chanson de Roland In: Revue de l'Occident musulman et de la Méditerranée, N°25, 1978. pp. 25-47. Citer ce document / Cite this document : Duval Paulette. La chronique du pseudo-Turpin et la Chanson de Roland. In: Revue de l'Occident musulman et de la Méditerranée, N°25, 1978. pp. 25-47. doi : 10.3406/remmm.1978.1802 http://www.persee.fr/web/revues/home/prescript/article/remmm_0035-1474_1978_num_25_1_1802 Abstract It seems to the author that the Chronique du Pseudo-Turpin and the Chanson de Roland refer to different Spains, both of them Christian, foes nevertheless : Navarre and Castille. Although the Pseudo- Turpin is impregnated with the Clunisian spirit of Croisade, the adoptionnist heresy appears in the controverse between Roland and Ferragus about the Trinity. So, one of the authors might have been a Spanish writer. The Santiago codex was registered by three people (instead of two, as it is too often said) and one may think the answer lays in this third author, — a woman. In the Chanson de Roland, the Norman poet seems devoted to the Islamic culture and to a mysticism derived from shi'ism. The name Baligant would refer to the Arabic name of the emir of Babylone (Babylone in Kgypt, not in Mesopotamia) ; the sword Joseuse would refer to the sword of the Imam, and Charles, too, would represent the Imam, himself. Last, the mentions of Apolin and Terrangan mean knowledge of the Table d'Emeraude translated by Hugh de Santalla for Miguel, the bishop of Tarrazone (1125-1151). -

The Song of Roland Has Some Connection to the History of Charlemagne's Failed Conquest of Spain in 778, but This Connection Is Rather Loose

Song of Roland Context: On the afternoon of August 15, 778, the rear guard of Charlemagne's army was massacred at Roncesvals, in the mountains between France and Spain. Einhard, Charlemagne's contemporary biographer, sets forth the incident as follows in his Life of Charlemagne: While the war with the Saxons was being fought incessantly and almost continuously, [Charlemagne] stationed garrisons at suitable places along the frontier and attacked Spain with the largest military force he could muster; he crossed the Pyrenees, accepted the surrender of all the towns and fortresses he attacked, and returned with his army safe and sound, except that he experienced a minor setback caused by Gascon treachery on returning through the passes of the Pyrenees. For while his army was stretched out in a long column, as the terrain and the narrow defiles dictated, the Gascons set an ambush above them on the mountaintops—an ideal spot for an ambush, due to the dense woods throughout the area—and rushing down into the valley, fell upon the end of the baggage train and the rear guard who served as protection for those in advance, and in the ensuing battle killed them to the last man, then seized the baggage, and under the cover of night, which was already falling, dispersed as quickly as possible. The Gascons were aided in this feat by the lightness of their armor and by the lay of the land where the action took place, whereas the Franks were hindered greatly by their heavy armor and the terrain. In this battle Eggihard, the surveyor of the royal table; Anselm, the count of the palace; and Roland, prefect of the Breton Marches, were killed, together with many others.