Definite Guide to Grails, 2006

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Definitive Guide to Grails

apress.com Graeme Rocher, Jeff Scott Brown The Definitive Guide to Grails This will be the first and only definitive book on the agile open source lightweight Grails (“Groovy on Rails” analogous to Ruby on Rails) Framework 1.0 release Written by the open source Grails project founder and lead, Graeme Rocher Emerging growth area with support from key open source lightweight projects like Spring, Hibernate, Wicket and more The rise of Ruby on Rails has signified a huge shift in how we build web applications today; it is a fantastic framework with a growing community. There is, however, space for another such framework that integrates seamlessly with Java. Thousands of companies have invested in Java, and these same companies are losing out on the benefits of a Rails–like framework. Enter Grails. Grails is not just a Rails clone. It aims to provide a Rails–like environment that is more familiar to Java developers and employs idioms that Java developers are comfortable 2nd ed., 648 p. using, making the adjustment in mentality to a dynamic framework less of a jump. The concepts within Grails, like interceptors, tag libs, and Groovy Server Pages (GSP), make those in Printed book the Java community feel right at home. Grails' foundation is on solid open source technologies Softcover such as Spring, Hibernate, and SiteMesh, which gives it even more potential in the Java space: 39,99 € | £36.99 | $46.99 Spring provides powerful inversion of control and MVC, Hibernate brings a stable, mature object [1]42,79 € (D) | 43,99 € (A) | CHF relational mapping technology with the ability to integrate with legacy systems, and SiteMesh 53,55 handles flexible layout control and page decoration. -

Ioc Containers in Spring

301AA - Advanced Programming Lecturer: Andrea Corradini [email protected] http://pages.di.unipi.it/corradini/ AP-2018-11: Frameworks and Inversion of Control Frameworks and Inversion of Control • Recap: JavaBeans as Components • Frameworks, Component Frameworks and their features • Frameworks vs IDEs • Inversion of Control and Containers • Frameworks vs Libraries • Decoupling Components • Dependency Injection • IoC Containers in Spring 2 Components: a recap A software component is a unit of composition with contractually specified interfaces and explicit context dependencies only. A software component can be deployed independently and is subject to composition by third party. Clemens Szyperski, ECOOP 1996 • Examples: Java Beans, CLR Assemblies • Contractually specified interfaces: events, methods and properties • Explicit context dependencies: serializable, constructor with no argument • Subject to composition: connection to other beans – Using connection oriented programming (event source and listeners/delegates) 3 Towards Component Frameworks • Software Framework: A collection of common code providing generic functionality that can be selectively overridden or specialized by user code providing specific functionality • Application Framework: A software framework used to implement the standard structure of an application for a specific development environment. • Examples: – GUI Frameworks – Web Frameworks – Concurrency Frameworks 4 Examples of Frameworks Web Application Frameworks GUI Toolkits 5 Examples: General Software Frameworks – .NET – Windows platform. Provides language interoperability – Android SDK – Supports development of apps in Java (but does not use a JVM!) – Cocoa – Apple’s native OO API for macOS. Includes C standard library and the Objective-C runtime. – Eclipse – Cross-platform, easily extensible IDE with plugins 6 Examples: GUI Frameworks • Frameworks for Application with GUI – MFC - Microsoft Foundation Class Library. -

Design Pattern Interview Questions

DDEESSIIGGNN PPAATTTTEERRNN -- IINNTTEERRVVIIEEWW QQUUEESSTTIIOONNSS http://www.tutorialspoint.com/design_pattern/design_pattern_interview_questions.htm Copyright © tutorialspoint.com Dear readers, these Design Pattern Interview Questions have been designed specially to get you acquainted with the nature of questions you may encounter during your interview for the subject of Design Pattern. As per my experience good interviewers hardly plan to ask any particular question during your interview, normally questions start with some basic concept of the subject and later they continue based on further discussion and what you answer: What are Design Patterns? Design patterns represent the best practices used by experienced object-oriented software developers. Design patterns are solutions to general problems that software developers faced during software development. These solutions were obtained by trial and error by numerous software developers over quite a substantial period of time. What is Gang of Four GOF? In 1994, four authors Erich Gamma, Richard Helm, Ralph Johnson and John Vlissides published a book titled Design Patterns - Elements of Reusable Object-Oriented Software which initiated the concept of Design Pattern in Software development. These authors are collectively known as Gang of Four GOF. Name types of Design Patterns? Design patterns can be classified in three categories: Creational, Structural and Behavioral patterns. Creational Patterns - These design patterns provide a way to create objects while hiding the creation logic, rather than instantiating objects directly using new opreator. This gives program more flexibility in deciding which objects need to be created for a given use case. Structural Patterns - These design patterns concern class and object composition. Concept of inheritance is used to compose interfaces and define ways to compose objects to obtain new functionalities. -

Dependency Injection with Unity

D EPEN DEPENDENCY INJECTION WITH UNITY Over the years software systems have evolutionarily become more and more patterns & practices D ENCY complex. One of the techniques for dealing with this inherent complexity Proven practices for predictable results of software systems is dependency injection – a design pattern that I allows the removal of hard-coded dependencies and makes it possible to Save time and reduce risk on your NJECT assemble a service by changing dependencies easily, whether at run-time software development projects by or compile-time. It promotes code reuse and loosely-coupled design which incorporating patterns & practices, I leads to more easily maintainable and flexible code. Microsoft’s applied engineering ON guidance that includes both production The guide you are holding in your hands is a primer on using dependency quality source code and documentation. W I injection with Unity – a lightweight extensible dependency injection TH DEPENDENCY INJECTION container built by the Microsoft patterns & practices team. It covers The guidance is designed to help U software development teams: various styles of dependency injection and also additional capabilities N I of Unity container, such as object lifetime management, interception, Make critical design and technology TY and registration by convention. It also discusses the advanced topics of selection decisions by highlighting WITH UNITY enhancing Unity with your custom extensions. the appropriate solution architectures, technologies, and Microsoft products The guide contains plenty of trade-off discussions and tips and tricks for for common scenarios managing your application cross-cutting concerns and making the most out of both dependency injection and Unity. These are accompanied by a Understand the most important Dominic Betts real world example that will help you master the techniques. -

Designpatternsphp Documentation Release 1.0

DesignPatternsPHP Documentation Release 1.0 Dominik Liebler and contributors Jul 18, 2021 Contents 1 Patterns 3 1.1 Creational................................................3 1.1.1 Abstract Factory........................................3 1.1.2 Builder.............................................8 1.1.3 Factory Method......................................... 13 1.1.4 Pool............................................... 18 1.1.5 Prototype............................................ 21 1.1.6 Simple Factory......................................... 24 1.1.7 Singleton............................................ 26 1.1.8 Static Factory.......................................... 28 1.2 Structural................................................. 30 1.2.1 Adapter / Wrapper....................................... 31 1.2.2 Bridge.............................................. 35 1.2.3 Composite............................................ 39 1.2.4 Data Mapper.......................................... 42 1.2.5 Decorator............................................ 46 1.2.6 Dependency Injection...................................... 50 1.2.7 Facade.............................................. 53 1.2.8 Fluent Interface......................................... 56 1.2.9 Flyweight............................................ 59 1.2.10 Proxy.............................................. 62 1.2.11 Registry............................................. 66 1.3 Behavioral................................................ 69 1.3.1 Chain Of Responsibilities................................... -

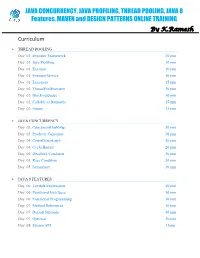

JAVA CONCURRENCY ONLINE TRAINING – Java2aspire

JAVA CONCURRENCY, JAVA PROFILING, THREAD POOLING, JAVA 8 Features, MAVEN and DESIGN PATTERNS ONLINE TRAINING By K.Ramesh Curriculum THREAD POOLING Day 01: Executor Framework 20 min Day 01: Java Profiling 10 min Day 01: Executor 10 min Day 01: ExecutorService 10 min Day 01: Executors 15 min Day 02: ThreadPoolExecutor 20 min Day 02: BlockingQueue 10 min Day 02: Callable vs Runnable 15 min Day 02: Future 15 min JAVA CONCURRENCY Day 03: ConcurrentHashMap 30 min Day 03: Producer Consumer 30 min Day 04: CountDownLatch 20 min Day 04: CyclicBarrier 20 min Day 04: Deadlock Condition 20 min Day 05: Race Condition 30 min Day 05: Semaphore 30 min JAVA 8 FEATURES Day 06: Lambda Expressions 40 min Day 06: Functional Interfaces 10 min Day 06: Functional Programming 10 min Day 07: Method References 10 min Day 07: Default Methods 40 min Day 07: Optional 10 min Day 08: Stream API 1 hour MAVEN Day 09: Project Object Model (POM) 20 min Day 09: Project Description 10 min Day 09: Public Repository 10 min Day 09: Dependency Management 10 min Day 09: Build Configuration 10 min Day 10: Installation 15 min Day 10: Dependency Scope 15 min Day 10: Proprietary Dependencies 15 min Day 10: Project Inheritance 15 min Day 11: Maven life cycle 20 min Day 11: Maven Directory Structure 20 min Day 11: Archetypes 20 min Day 12: Applications 1 hour DESIGN PATTERNS Day 13: Factory Pattern 20 min Day 13: Abstract Factory Pattern 10 min Day 13: Single Pattern 20 min Day 13: Prototype Pattern 10 min Day 14: Composite Pattern 10 min Day 14: Facade Pattern 15 min Day 14: DAO -

Pragmatic Bookshelf Groovy Recipes.Pdf

What readers are saying about Groovy Recipes This is the go-to guide for turning Groovy into every Java developer’s perfect utility knife. Whether you need to quickly parse an Atom feed, serve up an Excel spreadsheet from your Grails app, or create a tar- ball on the fly, this book will show you how. In true Groovy style, Scott does away with all unnecessary ceremony and gets right down to business. In almost every section, the very first thing you see is code— the recipe for solving the problem at hand—and if you want to stick around for the clear and informative explanation, well, that’s strictly optional. Jason Rudolph Author, Getting Started with Grails Groovy Recipes is the book that I want to have in reach whenever I work in my Groovy bakery. Nothing gets you faster up to speed than having well-thought-out recipes for your everyday tasks. Dierk König Canoo Engineering AG The format of this book is ideal for rapidly obtaining crucial informa- tion just when you need it. An agile text for agile development! Joe McTee Software Engineer, JEKLsoft Groovy is on my radar as one of the next big things in Java, and this book gets you up to speed quickly with lots of great code examples. David Geary Author, Clarity Training, Inc. Scott does a fantastic job of presenting many little nuggets of “groovi- ness” here in a way that is easy to read and follow. There is plenty here for Groovy newcomers and veterans alike. Thanks, Scott! Jeff Brown Member of the Groovy and Grails Core Development Teams Adding Groovy to Java is like adding rocket fuel to your SUV. -

Semantic Description of Services and Service Factories for Ambient Intelligence Rémi Emonet

Semantic Description of Services and Service Factories for Ambient Intelligence Rémi Emonet To cite this version: Rémi Emonet. Semantic Description of Services and Service Factories for Ambient Intelligence. Soft- ware Engineering [cs.SE]. Institut National Polytechnique de Grenoble - INPG, 2009. English. tel- 00450479 HAL Id: tel-00450479 https://tel.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-00450479 Submitted on 26 Jan 2010 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. GRENOBLE INP n◦ attribu´epar la biblioth`eque THESE` pour obtenir le grade de ❉♦❝❡✉ ❉✉ ●♦✉♣❡ ●❡♥♦❜❧❡ ■◆ Sp´ecialit´e: Informatique pr´epar´eeau Laboratoire d’Informatique de Grenoble dans le cadre de l’Ecole´ Doctorale Math´ematiques, Sciences et Technologies de l’Information, Informatique pr´esent´eeet soutenue publiquement par R´emi ❊♠♦♥❡ le 23 septembre 2009 ❉❡❝✐♣✐♦♥ ❙♠❛♥✐✉❡ ❞❡ ❙❡✈✐❝❡ ❡ ❞✬❯✐♥❡ à ❙❡✈✐❝❡ ♣♦✉ ❧✬■♥❡❧❧✐❣❡♥❝❡ ❆♠❜✐❛♥❡ ❙❡♠❛♥✐❝ ❉❡❝✐♣✐♦♥ ♦❢ ❙❡✈✐❝❡ ❛♥❞ ❙❡✈✐❝❡ ❋❛❝♦✐❡ ❢♦ ❆♠❜✐❡♥ ■♥❡❧❧✐❣❡♥❝❡ Directeur de th`ese : James L. ❈♦✇❧❡② Co-directeur de th`ese : Dominique ❱❛✉❢❡②❞❛③ JURY Pr. Marie-Christine Rousset Pr´esident Pr. James L. Crowley Directeur de th`ese Dr. Dominique Vaufreydaz Co-directeur de th`ese Pr. Gregory D. Abowd Rapporteur Pr. David Simplot-Ryl Rapporteur Pr. Michel Riveill Examinateur 2 R´esum´e Ce manuscrit ´etudie l’ad´equation des approches `aservices, ainsi que leur am´elioration, pour l’int´egration dynamique et la r´eutilisation logicielle dans le cadre de l’informatique ambiante. -

Sun Certified Enterprise Architect for Java EE Study Guide / Mark Cade, Humphrey Sheil

Many of the designations used by manufacturers and sellers to distinguish their products are claimed as trademarks. Where those designations appear in this book, and the publisher was aware of a trademark claim, the designations have been printed with initial capital letters or in all capitals. Sun Microsystems, Inc. has intellectual property rights relating to implementations of the technology described in this publication. In particular, and without limitation, these intellectual property rights may include one or more U.S. patents, foreign patents, or pending applications. Sun, Sun Microsystems, the Sun logo, J2ME, J2EE, Java Card, and all Sun and Java based trademarks and logos are trademarks or registered trademarks of Sun Microsystems, Inc., in the United States and other countries. UNIX is a registered trademark in the United States and other countries, exclusively licensed through X/Open Company, Ltd. This publication is provided “as is” without warranty of any kind, either express or implied, including, but not limited to, the implied warranties of merchantability, fitness for a particular purpose, or non-infringement. This publication could include technical inaccuracies or typographical errors. Changes are periodically added to the information herein; these changes will be incorporated in new editions of the publication. Sun Microsystems, Inc. may make improvements and/or changes in the product(s) and/or the program(s) described in this publication at any time. The authors and publisher have taken care in the preparation of this book, but make no expressed or implied warranty of any kind and assume no responsibility for errors or omissions. No liability is assumed for incidental or consequential damages in connection with or arising out of the use of the information or programs contained herein. -

Preparing for Banner Powered by Ellucian XE

Preparing for Banner powered by Ellucian XE Mark Hoye, Services Portfolio Consultant Ellucian September 25, 2015 Introduction • This session is about moving forward with Banner powered by Ellucian XE. • It explains Ellucian XE, how it adds value to your investment in Banner, and how you can take advantage of its power today. © 2015 ELLUCIAN. ALL RIGHTS RSERVED Agenda 1 Ellucian XE 2 Banner powered by Ellucian XE 3 Preparing for Banner powered by Ellucian XE 4 Summary and Questions © 2015 ELLUCIAN. ALL RIGHTS RSERVED Ellucian XE Ellucian: Future-proof Technology Evolutionary approach Extensible ecosystem strategy Global and mobile-first technology strategy Published roadmaps and product plans Investment in our products and our processes protects our customers’ investments © 2015 ELLUCIAN. ALL RIGHTS RSERVED The XE Strategy and Design Principles Mobile Self-Service Admin UI Cloud XE Design Principles Usability Features/Func7on Cloud Readiness/Scalability Configuraon over Customizaon Extensibility APIs/Integraon Single Global Product © 2015 ELLUCIAN. ALL RIGHTS RSERVED Banner powered by Ellucian XE Applications Leveraging XE Strategy Banner Applications Integrated Applications • Catalog & Schedule • Ellucian eTranscripts • Faculty Grade Entry • Ellucian Mobile • Attendance Tracking • Ellucian Elevate • Event Management • Ellucian Pilot (Student Success) • Advising Student Profile • Ellucian Portal for Banner • Student Registration • Intelligent Learning Platform (ILP) • Employee Profile • APIs (Services) • Academic history • Student • Communication Management © 2015 ELLUCIAN. ALL RIGHTS RSERVED ReSTful services and the Higher Education Data Model • Expose “Resources” - important concepts and objects • Each resource is uniquely Resources (Nouns) “addressable” • Provide “representations” of those resources Verbs • Provide a consistent interface (Get, Post, Put, Delete) based upon standard HTTP methods • Interaction with the API is stateless Output (XML, JSON) © 2015 ELLUCIAN. -

The Definitive Guide to Grails

G. Rocher, J.S. Brown The Definitive Guide to Grails ▶ This will be the first and only definitive book on the agile open source lightweight Grails (“Groovy on Rails” analogous to Ruby on Rails) Framework 1.0 release ▶ Written by the open source Grails project founder and lead, Graeme Rocher ▶ Emerging growth area with support from key open source lightweight projects like Spring, Hibernate, Wicket and more The rise of Ruby on Rails has signified a huge shift in how we build web applications today; it is a fantastic framework with a growing community. There is, however, space for another such framework that integrates seamlessly with Java. Thousands of companies have invested in Java, and these same companies are losing out on the benefits of a Rails– 2nd ed., 648 p. like framework. Enter Grails. A product of Apress Grails is not just a Rails clone. It aims to provide a Rails–like environment that is more familiar to Java developers and employs idioms that Java developers are comfortable Printed book using, making the adjustment in mentality to a dynamic framework less of a jump. The concepts within Grails, like interceptors, tag libs, and Groovy Server Pages (GSP), make Softcover those in the Java community feel right at home. ▶ 39,99 € | £36.99 | $46.99 ▶ *42,79 € (D) | 43,99 € (A) | CHF 53.55 Grails' foundation is on solid open source technologies such as Spring, Hibernate, and SiteMesh, which gives it even more potential in the Java space: Spring provides powerful eBook inversion of control and MVC, Hibernate brings a stable, mature object relational mapping technology with the ability to integrate with legacy systems, and SiteMesh handles Available from your bookstore or flexible layout control and page decoration. -

J2EE Architecture and Patterns in Enterprise Systems

J2EE Architecture and Patterns in Enterprise Systems Zhiguo Guo University of Tampere Department of Computer and Information Science Master’s Thesis May 2004 i University of Tampere Department of Computer and Information Science Zhiguo Guo: J2EE Architecture and Patterns in Enterprise Systems Master’s Thesis, 60 pages May 2004 The purpose of this thesis is to illustrate an enterprise project named HUVA, in which Java Platform 2, Enterprise Edition (J2EE) architecture and patterns are applied. This study took a constructive research approach: It starts from the application domain including the initial plan and business model, then moves to the system architecture covering the architecturally significant requirements and the system structure compliant with J2EE architecture, finally ends at the application design elaborated by applying the J2EE patterns at a high level. As a result the architectural and application design satisfied the project needs and requirements; and the HUVA software has been implemented in practice according to the design. Keywords: J2EE, architecture, pattern, enterprise system. ii Acknowledgements I would like to thank Professor Roope Raisamo and Professor Isto Aho from the University of Tampere for being my encouraging, patient and responsible supervisors during the master’s thesis project. I would like to thank Mr. Mika Miettinen from Solteq Oyj and Mr. Timo Westkämper for supporting the technical aspects of this thesis. Finally, I would like to use this opportunity to express huge thanks to my dear wife, Chongliang Tang for always being the invaluable person behind my success. Tampere - Finland, June 1st, 2004 Zhiguo Guo iii Contents 1. Introduction.............................................................................................................1 2. Application domain ...............................................................................................3 2.1.