Decoding Chinese Politics Intellectual Debates and Why They Matter

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chen Xitong Report on Putting Down Anti

Recent Publications The June Turbulence in Beijing How Chinese View the Riot in Beijing Fourth Plenary Session of the CPC Central Committee Report on Down Anti-Government Riot Retrospective After the Storm VOA Disgraces Itself Report on Checking the Turmoil and Quelling the Counter-Revolutionary Rebellion June 30, 1989 Chen Xitong, State Councillor and Mayor of Beijing New Star Publishers Beijing 1989 Report on Checking the Turmoil and Quelling the Counter-Revolutionary Rebellion From June 29 to July 7 the Standing Committee of the National People's Congress - the standing organization of the highest organ of state power in the People's Republic of China - held the eighth meeting of the Seventh National People's Congress in Beijing. One of the topics for discussing at the meeting was a report on checking the turmoil and quelling the counter-revolutionary rebellion in Beijirig. The report by state councillor and mayor of Beijing Chen Xitong explained in detail the process by which a small group of people made use of the student unrest in Beijing and turned it into a counter-revolutionary rebellion by mid-June. It gave a detailed account of the nature of the riot, its severe conse- quence and the efforts made by troops enforcing _martial law, with the help of Beijing residents to quell the riot. The report exposed the behind-the-scene activities of people who stub- bornly persisted in opposing the Chinese Communist Party and socialism as well as the small handful of organizers and schemers of the riot; their collaboration with antagonistic forces at home and abroad; and the atrocities committed by former criminals in beating, looting, burning and First Edition 1989 killing in the riot. -

Confession, Redemption, and Death: Liu Xiaobo and the Protest Movement of 1989

Confession, Redemption, and Death: Liu Xiaobo and the Protest Movement of 1989 Geremie Barmé1 There should be room for my extremism; I certainly don’t demand of others that they be like me... I’m pessimistic about mankind in general, but my pessimism does not allow for escape. Even though I might be faced with nothing but a series of tragedies, I will still struggle, still show my opposition. This is why I like Nietzsche and dislike Schopenhauer. Liu Xiaobo, November 19882 I FROM 1988 to early 1989, it was a common sentiment in Beijing that China was in crisis. Economic reform was faltering due to the lack of a coherent program of change or a unified approach to reforms among Chinese leaders and ambitious plans to free prices resulted in widespread panic over inflation; the question of political succession to Deng Xiaoping had taken alarming precedence once more as it became clear that Zhao Ziyang was under attack; nepotism was rife within the Party and corporate economy; egregious corruption and inflation added to dissatisfaction with educational policies and the feeling of hopelessness among intellectuals and university students who had profited little from the reforms; and the general state of cultural malaise and social ills combined to create a sense of impending doom. On top of this, the government seemed unwilling or incapable of attempting to find any new solutions to these problems. It enlisted once more the aid of propaganda, empty slogans, and rhetoric to stave off the mounting crisis. University students in Beijing appeared to be particularly heavy casualties of the general malaise. -

Hong Kong SAR

China Data Supplement November 2006 J People’s Republic of China J Hong Kong SAR J Macau SAR J Taiwan ISSN 0943-7533 China aktuell Data Supplement – PRC, Hong Kong SAR, Macau SAR, Taiwan 1 Contents The Main National Leadership of the PRC 2 LIU Jen-Kai The Main Provincial Leadership of the PRC 30 LIU Jen-Kai Data on Changes in PRC Main Leadership 37 LIU Jen-Kai PRC Agreements with Foreign Countries 47 LIU Jen-Kai PRC Laws and Regulations 50 LIU Jen-Kai Hong Kong SAR 54 Political, Social and Economic Data LIU Jen-Kai Macau SAR 61 Political, Social and Economic Data LIU Jen-Kai Taiwan 65 Political, Social and Economic Data LIU Jen-Kai ISSN 0943-7533 All information given here is derived from generally accessible sources. Publisher/Distributor: GIGA Institute of Asian Affairs Rothenbaumchaussee 32 20148 Hamburg Germany Phone: +49 (0 40) 42 88 74-0 Fax: +49 (040) 4107945 2 November 2006 The Main National Leadership of the PRC LIU Jen-Kai Abbreviations and Explanatory Notes CCP CC Chinese Communist Party Central Committee CCa Central Committee, alternate member CCm Central Committee, member CCSm Central Committee Secretariat, member PBa Politburo, alternate member PBm Politburo, member Cdr. Commander Chp. Chairperson CPPCC Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference CYL Communist Youth League Dep. P.C. Deputy Political Commissar Dir. Director exec. executive f female Gen.Man. General Manager Gen.Sec. General Secretary Hon.Chp. Honorary Chairperson H.V.-Chp. Honorary Vice-Chairperson MPC Municipal People’s Congress NPC National People’s Congress PCC Political Consultative Conference PLA People’s Liberation Army Pol.Com. -

The Case of the United Nations, the Collective Security Treaty Organization and the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation1

MULTILateRAL INSTITUTIONS UNDER STRESS? The Interconnection of Global and Regional Security Systems: the Case of the United Nations, the Collective Security Treaty Organization and the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation1 S. Bokeriya Svetlana Bokeriya ‒ PhD, Associate Professor, Department of Theory and History of International Relations, Peoples’ Friendship University of Russia; 10 MiklukhoMaklaya Str., Moscow, 117198, Russian Federation; Email: [email protected] Abstract This article studies the interconnection of global and regional security systems using the example of the interaction of the United Nations (UN) with the Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO) and the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO). According to the author, their activity is underestimated. These organizations appeared in the wake of the emergence of a pool of regional associations of countries that have become involved in security and peacekeeping activities. Both associations have a similar composition of members, were established after the collapse of the USSR, are observers in the UN, are engaged in security as one of their key activities, and have similar functions. The CSTO and the SCO prevented new conflicts from breaking out in the post-Soviet space by acting as stabilizing forces within the borders of their regions and the participating states. This study’s relevance is underscored first, by the special role that regional organizations play in building and operating a global security system; second, by the lack of existing research focused on the interaction of the UN with the CSTO and the SCO; and third, by the need to improve the collective mechanisms for responding to new security threats which become intertwined with existing challenges. -

Of the Liberation Army

HO LU NG DEMOCRATIC TRADITION OF THE CHINESE PEOPLE'S LIBERATION ARMY trtro l,tiNG DHI\'EOCIIATIC TRr}'tlITI CIN OF TE{N CHINIISE FEOPLE'$ f"}.BEIIATION AHMY ,'[rt$tlll I. 1$fiS POREIGN LAI,iGUAGES PRNSS PEI{ING 1O6J PUELISHER'S ]VO?E fundamental criterion for distinguishing a revolu- tior-rary army led by the proleiariat from alt This article LtuTg, Meml:er Politicai. by Ho o.[ the counter-t"evolutior-rary armies 1ed by the reactionary rul- Fluleau of the Centi'a1 Con:mittee of the Chin.ese Corn- ing classes, as far as internal relations ale concerned, is t:-runist Part;', Vice-Premier of the State Council and rvhether theie is democracy in liie arnry. is common Vice-Chairman of the National Delence Council of the It knorvledge that a1l alrnies are irrstluments dictator+ People's Republic of China, r,vas published on Augusfl of 1, 1965" lire S8tli anniversary of the founcling <lf the ship. Counler-revolutionarv aLru.ies ol the r.eactionary Cirinese Feo1.:le's l,iberaticrn AlnTy- ruling classes are instruments of dicLaiorship over the nlasses oI the people, lvhile a proletarian revolutionary army is an instrument of dictatorship r:ver the counter- revolutionaries. Since they represent the interests of a handful oI peopie, all counter-levolulionary armies of the reactionary ruling classes are hostile to the lnasses, \,vho complise over 90 per cent of the population. Therefore, they do not clale to pr-actise democracy wiihin their ranl<s. By contrast, a revolutionary army led by the proletariat is a people's army which safeguards the in- terests of the workers, peasants and othei'sections oJ the working people u4ro comprise ovelr 90 per cent of the pop- ulation. -

Promoting Logistics Development in Rural Areas

Promoting Logistics Development in Rural Areas Logistics plays an important role in agricultural production and supply-chain management, ultimately enhancing food safety and quality. Improvements in rural logistics help farmers to harvest and market crops more e ciently; and by facilitating communication, they serve to expand the markets for agricultural products. While recognizing the rapidly changing rural landscape in the People’s Republic of China, the distribution of goods is still impeded, and the quality of services poor. This study is part of the Asian Development Bank’s initiative to support and promote the development of the agriculture sector and establish e cient rural–urban synergies. Read how the private and public sectors can improve and promote logistics development in rural areas. About the Asian Development Bank ADB’s vision is an Asia and Pacifi c region free of poverty. Its mission is to help its developing member countries reduce poverty and improve the quality of life of their people. Despite the region’s many successes, it remains home to a large share of the world’s poor. ADB is committed to reducing poverty through inclusive economic growth, environmentally sustainable growth, and regional integration. Based in Manila, ADB is owned by members, including from the region. Its main instruments for helping its developing member countries are policy dialogue, loans, equity investments, guarantees, grants, and technical assistance. PROMOTING LOGISTICS DEVELOPMENT IN RURAL AREAS ASIAN DEVELOPMENT BANK 6 ADB Avenue, Mandaluyong City 1550 Metro Manila. Philippines 9 789292 579913 ASIAN DEVELOPMENT BANK www.adb.org PROMOTING LOGISTICS DEVELOPMENT IN RURAL AREAS ASIAN DEVELOPMENT BANK Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 IGO license (CC BY 3.0 IGO) © 2017 Asian Development Bank 6 ADB Avenue, Mandaluyong City, 1550 Metro Manila, Philippines Tel +63 2 632 4444; Fax +63 2 636 2444 www.adb.org Some rights reserved. -

China's Domestic Politicsand

China’s Domestic Politics and Foreign Policies and Major Countries’ Strategies toward China edited by Jung-Ho Bae and Jae H. Ku China’s Domestic Politics and Foreign Policies and Major Countries’ Strategies toward China 1SJOUFE %FDFNCFS 1VCMJTIFE %FDFNCFS 1VCMJTIFECZ ,PSFB*OTUJUVUFGPS/BUJPOBM6OJGJDBUJPO ,*/6 1VCMJTIFS 1SFTJEFOUPG,*/6 &EJUFECZ $FOUFSGPS6OJGJDBUJPO1PMJDZ4UVEJFT ,*/6 3FHJTUSBUJPO/VNCFS /P "EESFTT SP 4VZVEPOH (BOHCVLHV 4FPVM 5FMFQIPOF 'BY )PNFQBHF IUUQXXXLJOVPSLS %FTJHOBOE1SJOU )ZVOEBJ"SUDPN$P -UE $PQZSJHIU ,*/6 *4#/ 1SJDF G "MM,*/6QVCMJDBUJPOTBSFBWBJMBCMFGPSQVSDIBTFBUBMMNBKPS CPPLTUPSFTJO,PSFB "MTPBWBJMBCMFBU(PWFSONFOU1SJOUJOH0GGJDF4BMFT$FOUFS4UPSF 0GGJDF China’s Domestic Politics and Foreign Policies and Major Countries’ Strategies toward China �G 1SFGBDF Jung-Ho Bae (Director of the Center for Unification Policy Studies at Korea Institute for National Unification) �G *OUSPEVDUJPO 1 Turning Points for China and the Korean Peninsula Jung-Ho Bae and Dongsoo Kim (Korea Institute for National Unification) �G 1BSUEvaluation of China’s Domestic Politics and Leadership $IBQUFS 19 A Chinese Model for National Development Yong Shik Choo (Chung-Ang University) $IBQUFS 55 Leadership Transition in China - from Strongman Politics to Incremental Institutionalization Yi Edward Yang (James Madison University) $IBQUFS 81 Actors and Factors - China’s Challenges in the Crucial Next Five Years Christopher M. Clarke (U.S. State Department’s Bureau of Intelligence and Research-INR) China’s Domestic Politics and Foreign Policies -

The Case of Zhang Yiwu

ASIA 2016; 70(3): 921–941 Giorgio Strafella* Postmodernism as a Nationalist Conservatism? The Case of Zhang Yiwu DOI 10.1515/asia-2015-1014 Abstract: The adoption of postmodernist and postcolonial theories by China’s intellectuals dates back to the early 1990s and its history is intertwined with that of two contemporaneous trends in the intellectual sphere, i. e. the rise of con- servatism and an effort to re-define the function of the Humanities in the country. This article examines how these trends merge in the political stance of a key figure in that process, Peking University literary scholar Zhang Yiwu, through a critical discourse analysis of his writings from the early and mid- 1990s. Pointing at his strategic use of postmodernist discourse, it argues that Zhang Yiwu employed a legitimate critique of the concept of modernity and West-centrism to advocate a historical narrative and a definition of cultural criticism that combine Sino-centrism and depoliticisation. The article examines programmatic articles in which the scholar articulated a theory of the end of China’s “modernity”. It also takes into consideration other parallel interventions that shed light on Zhang Yiwu’s political stance towards modern China, globalisation and post-1992 economic reforms, including a discussion between Zhang Yiwu and some of his most prominent detractors. The article finally reflects on the implications of Zhang Yiwu’s writings for the field of Chinese Studies, in particular on the need to look critically and contextually at the adoption of “foreign” theoretical discourse for national political agendas. Keywords: China, intellectuals, postmodernism, Zhang Yiwu, conservatism, nationalism 1 Introduction This article looks at the early history and politics of the appropriation of post- modernist discourse in the Chinese intellectual sphere, thus addressing the plurality of postmodernity via the plurality of postmodernism. -

The Danger of Deconsolidation Roberto Stefan Foa and Yascha Mounk Ronald F

July 2016, Volume 27, Number 3 $14.00 The Danger of Deconsolidation Roberto Stefan Foa and Yascha Mounk Ronald F. Inglehart The Struggle Over Term Limits in Africa Brett L. Carter Janette Yarwood Filip Reyntjens 25 Years After the USSR: What’s Gone Wrong? Henry E. Hale Suisheng Zhao on Xi Jinping’s Maoist Revival Bojan Bugari¡c & Tom Ginsburg on Postcommunist Courts Clive H. Church & Adrian Vatter on Switzerland Daniel O’Maley on the Internet of Things Delegative Democracy Revisited Santiago Anria Catherine Conaghan Frances Hagopian Lindsay Mayka Juan Pablo Luna Alberto Vergara and Aaron Watanabe Zhao.NEW saved by BK on 1/5/16; 6,145 words, including notes; TXT created from NEW by PJC, 3/18/16; MP edits to TXT by PJC, 4/5/16 (6,615 words). AAS saved by BK on 4/7/16; FIN created from AAS by PJC, 4/25/16 (6,608 words). PGS created by BK on 5/10/16. XI JINPING’S MAOIST REVIVAL Suisheng Zhao Suisheng Zhao is professor at the Josef Korbel School of International Studies, University of Denver. He is executive director of the univer- sity’s Center for China-U.S. Cooperation and editor of the Journal of Contemporary China. When Xi Jinping became paramount leader of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) in 2012, some Chinese intellectuals with liberal lean- ings allowed themselves to hope that he would promote the cause of political reform. The most optimistic among them even thought that he might seek to limit the monopoly on power long claimed by the ruling Chinese Communist Party (CCP). -

News China March. 13.Cdr

VOL. XXV No. 3 March 2013 Rs. 10.00 The first session of the 12th National People’s Congress (NPC) opens at the Great Hall of the People in Beijing, capital of China on March 5, 2013. (Xinhua/Pang Xinglei) Chinese Ambassador to India Mr. Wei Wei meets Indian Chinese Vice Foreign Minister Cheng Guoping , on behalf Foreign Minister Salman Khurshid in New Delhi on of State Councilor Dai Bingguo, attends the dialogue on February 25, 2013. During the meeting the two sides Afghanistan issue held in Moscow,together with Russian exchange views on high-level interactions between the two Security Council Secretary Nikolai Patrushev and Indian countries, economic and trade cooperation and issues of National Security Advisor Shivshankar Menon on February common concern. 20, 2013. Chinese Ambassador to India Mr.Wei Wei and other VIP Chinese Ambassador to India Mr. Wei Wei and Indian guests are having a group picture with actors at the 2013 Minister of Culture Smt. Chandresh Kumari Katoch enjoy Happy Spring Festival organized by the Chinese Embassy “China in the Spring Festival” exhibition at the 2013 Happy and FICCI in New Delhi on February 25,2013. Artists from Spring Festival. The exhibition introduces cultures, Jilin Province, China and Punjab Pradesh, India are warmly customs and traditions of Chinese Spring Festival. welcomed by the audience. Chinese Ambassador to India Mr. Wei Wei(third from left) Chinese Ambassador to India Mr. Wei Wei visits the participates in the “Happy New Year “ party organized by Chinese Visa Application Service Centre based in the Chinese Language Department of Jawaharlal Nehru Southern Delhi on March 6, 2013. -

Yining Li Influence of Ethical Factors on Economy

China Academic Library Yining Li Beyond Market and Government In uence of Ethical Factors on Economy China Academic Library Academic Advisory Board: Researcher Geng, Yunzhi, Institute of Modern History, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, China Professor Han, Zhen, Beijing Foreign Studies University, China Researcher Hao, Shiyuan, Institute of Ethnology and Anthropology, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, China Professor Li, Xueqin, Department of History, Tsinghua University, China Professor Li, Yining, Guanghua School of Management, Peking University, China Researcher Lu, Xueyi, Institute of Sociology, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, China Professor Tang, Yijie, Department of Philosophy, Peking University, China Professor Wong, Young-tsu, Department of History, Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, USA Professor Yu, Keping, Central Compilation and Translation Bureau, China Professor Yue, Daiyun, Department of Chinese Language and Literature, Peking University, China Zhu, Yinghuang, China Daily Press, China Series Coordinators: Zitong Wu, Foreign Language Teaching and Research Press, China Yan Li, Springer More information about this series at http://www.springer.com/series/11562 Yining Li Beyond Market and Government Infl uence of Ethical Factors on Economy Yining Li Guanghua School of Management Peking University Beijing , China Sponsored by Chinese Fund for the Humanities and Social Sciences (ᵜҖ㧧ѝॾ⽮Պ、ᆖส䠁䍴ࣙ) ISSN 2195-1853 ISSN 2195-1861 (electronic) ISBN 978-3-662-44253-1 ISBN 978-3-662-44254-8 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-3-662-44254-8 Springer Heidelberg New York Dordrecht London Library of Congress Control Number: 2014944134 © Foreign Language Teaching and Research Publishing Co., Ltd and Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg 2015 This work is subject to copyright. -

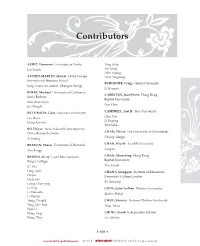

Contributors.Indd Page 569 10/20/15 8:21 AM F-479 /203/BER00069/Work/Indd/%20Backmatter

02_Contributors.indd Page 569 10/20/15 8:21 AM f-479 /203/BER00069/work/indd/%20Backmatter Contributors AUBIÉ, Hermann University of Turku Yang Jiang Liu Xiaobo Yao Ming Zhao Ziyang AUSTIN-MARTIN, Marcel China Europe Zhou Youguang International Business School BURGDOFF, Craig Capital University Jiang Zemin (co-author: Zhengxu Wang) Li Hongzhi BERRY, Michael University of California, CABESTAN, Jean-Pierre Hong Kong Santa Barbara Baptist University Hou Hsiao-hsien Lien Chan Jia Zhangke CAMPBELL, Joel R. Troy University BETTINSON, Gary Lancaster University Chen Yun Lee, Bruce Li Keqiang Wong Kar-wai Wen Jiabao BO Zhiyue New Zealand Contemporary CHAN, Felicia The University of Manchester China Research Centre Cheung, Maggie Xi Jinping BRESLIN, Shaun University of Warwick CHAN, Hiu M. Cardiff University Zhu Rongji Gong Li BROWN, Kerry Lau China Institute, CHAN, Shun-hing Hong Kong King’s College Baptist University Bo Yibo Zen, Joseph Fang Lizhi CHANG Xiangqun Institute of Education, Hu Jia University College London Hu Jintao Fei Xiaotong Leung Chun-ying Li Peng CHEN, Julie Yu-Wen Palacky University Li Xiannian Kadeer, Rebiya Li Xiaolin Tsang, Donald CHEN, Szu-wei National Taiwan University Tung Chee-hwa Teng, Teresa Wan Li Wang Yang CHING, Frank Independent Scholar Wang Zhen Lee, Martin • 569 • www.berkshirepublishing.com © 2015 Berkshire Publishing grouP, all rights reserved. 02_Contributors.indd Page 570 9/22/15 12:09 PM f-500 /203/BER00069/work/indd/%20Backmatter • Berkshire Dictionary of Chinese Biography • Volume 4 • COHEN, Jerome A. New