Wall Paintings in the Synagogue of Rehov: an Account of Their Discovery

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(I) Interim Report on the Fort Near Tel Shalem

Capricorno Alae VII Phrygum ... (i) Interim report on the fort near Tel Shalem Benjamin Arubas, Michael Heinzelmann, David Mevorah and Andrew Overman A multi-disciplinary research proj- ect has been begun in the fields next to the site of Tel Shalem (fig. 1), the locus of important discoveries since the 1970s (primarily the bronze statue of Hadrian). Recent geophysical prospections have detected the clear layout of a Roman fort and possibly even two successive forts. Two short excavation seasons carried out in 2017 and 2019, with a focus on the prin- cipia, resulted in finds that shed new light on the nature, history and identity of the site. Tel Shalem lies in the plain of the Jor- dan Rift Valley c.2 km west of the river and close to the territories of two Decapo- lis cities (it is c.10 km southwest of Pella and c.12 km south-southeast of Nysa- Scythopolis). It controls a major junction of the road network. The highway which connects to the Via Maris running along the coast passes through the Jezreel, Fig. 1. Map of the Roman province of Judaea / Syria Bet She’an and Jordan valleys and, after Palaestina (M. Heinzelmann; archive AI UoC). crossing the Jordan river, continues either northwards to Syria or eastwards to the Trans- Jordan highlands. This road intersects other routes, one of which runs southwards along the Rift Valley past the Sea of Galilee through Scythopolis to Jerusalem by way of Jericho, the other of which runs from Neapolis (Nablus) in Samaria to Pella through Nahal Bezek (Wadi Shubash). -

Migration of Eretz Yisrael Arabs Between December 1, 1947 and June 1, 1948

[Intelligence Service (Arab Section)] June 30, 1948 Migration of Eretz Yisrael Arabs between December 1, 1947 and June 1, 1948 Contents 1. General introduction. 2. Basic figures on Arab migration 3. National phases of evacuation and migration 4. Causes of Arab migration 5. Arab migration trajectories and absorption issues Annexes 1. Regional reviews analyzing migration issues in each area [Missing from document] 2. Charts of villages evacuated by area, noting the causes for migration and migration trajectories for every village General introduction The purpose of this overview is to attempt to evaluate the intensity of the migration and its various development phases, elucidate the different factors that impacted population movement directly and assess the main migration trajectories. Of course, given the nature of statistical figures in Eretz Yisrael in general, which are, in themselves, deficient, it would be difficult to determine with certainty absolute numbers regarding the migration movement, but it appears that the figures provided herein, even if not certain, are close to the truth. Hence, a margin of error of ten to fifteen percent needs to be taken into account. The figures on the population in the area that lies outside the State of Israel are less accurate, and the margin of error is greater. This review summarizes the situation up until June 1st, 1948 (only in one case – the evacuation of Jenin, does it include a later occurrence). Basic figures on Arab population movement in Eretz Yisrael a. At the time of the UN declaration [resolution] regarding the division of Eretz Yisrael, the following figures applied within the borders of the Hebrew state: 1. -

Eusebius and His Ecclesiastical History

1 Eusebius and His Ecclesiastical History Eusebius’s Ecclesiastical History (HE) is the most important of his many books. It created a new literary genre that would have a long and influential history. In an often-quoted statement, F. C. Baur called Eusebius the father of ecclesiastical his- tory, just as Herodotus was the father of historical writing in general.1 The Ecclesi- astical History is our single most important source for recovering the history of the first three centuries of Christianity. And it is the centerpiece of a corpus of writings in which Eusebius created a distinctive vision of the place of the Christian church in world history and God’s providential plan. A book of such significance has attracted an enormous body of commentary and analysis driven by two rather different motives. One was the value of the HE as a documentary treasure trove of partially or completely lost works. For a long time, that was the primary driver of scholarly interest. The past two generations have seen the emergence of a second trend that focuses on Eusebius as a figure in his own right, a writer of exceptional range, creativity, and productivity, and an actor on the ecclesiastical and political stage.2 How, for example, did current events shape the way Eusebius thought and wrote about the church’s past? And what can his con- struction of the past tell us in turn about Christian consciousness and ambition during a time of enormous transition? Seen from that angle, the HE becomes not a source for history but itself an artifact of history, a hermeneutical redirection that will be applied to other works of Christian historiography in this book.3 1. -

Three Conquests of Canaan

ÅA Wars in the Middle East are almost an every day part of Eero Junkkaala:of Three Canaan Conquests our lives, and undeniably the history of war in this area is very long indeed. This study examines three such wars, all of which were directed against the Land of Canaan. Two campaigns were conducted by Egyptian Pharaohs and one by the Israelites. The question considered being Eero Junkkaala whether or not these wars really took place. This study gives one methodological viewpoint to answer this ques- tion. The author studies the archaeology of all the geo- Three Conquests of Canaan graphical sites mentioned in the lists of Thutmosis III and A Comparative Study of Two Egyptian Military Campaigns and Shishak and compares them with the cities mentioned in Joshua 10-12 in the Light of Recent Archaeological Evidence the Conquest stories in the Book of Joshua. Altogether 116 sites were studied, and the com- parison between the texts and the archaeological results offered a possibility of establishing whether the cities mentioned, in the sources in question, were inhabited, and, furthermore, might have been destroyed during the time of the Pharaohs and the biblical settlement pe- riod. Despite the nature of the two written sources being so very different it was possible to make a comparative study. This study gives a fresh view on the fierce discus- sion concerning the emergence of the Israelites. It also challenges both Egyptological and biblical studies to use the written texts and the archaeological material togeth- er so that they are not so separated from each other, as is often the case. -

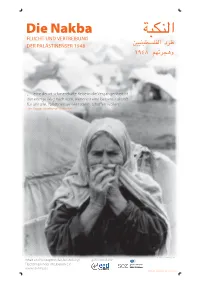

Die Nakba – Flucht Und Vertreibung Der Palästinenser 1948

Die Nakba FLUCHT UND VERTREIBUNG DER PALÄSTINENSER 1948 „… eine derart schmerzhafte Reise in die Vergangenheit ist der einzige Weg nach vorn, wenn wir eine bessere Zukunft für uns alle, Palästinenser wie Israelis, schaffen wollen.“ Ilan Pappe, israelischer Historiker Gestaltung: Philipp Rumpf & Sarah Veith Inhalt und Konzeption der Ausstellung: gefördert durch Flüchtlingskinder im Libanon e.V. www.lib-hilfe.de © Flüchtlingskinder im Libanon e.V. 1 VON DEN ERSTEN JÜDISCHEN EINWANDERERN BIS ZUR BALFOUR-ERKLÄRUNG 1917 Karte 1: DER ZIONISMUS ENTSTEHT Topographische Karte von Palästina LIBANON 01020304050 km Die Wurzeln des Palästina-Problems liegen im ausgehenden 19. Jahrhundert, als Palästina unter 0m Akko Safed SYRIEN Teil des Osmanischen Reiches war. Damals entwickelte sich in Europa der jüdische Natio- 0m - 200m 200m - 400m Haifa 400m - 800m nalismus, der so genannte Zionismus. Der Vater des politischen Zionismus war der öster- Nazareth reichisch-ungarische Jude Theodor Herzl. Auf dem ersten Zionistenkongress 1897 in Basel über 800m Stadt wurde die Idee des Zionismus nicht nur auf eine breite Grundlage gestellt, sondern es Jenin Beisan wurden bereits Institutionen ins Leben gerufen, die für die Einwanderung von Juden nach Palästina werben und sie organisieren sollten. Tulkarm Qalqilyah Nablus MITTELMEER Der Zionismus war u.a. eine Antwort auf den europäischen Antisemitismus (Dreyfuß-Affäre) und auf die Pogrome vor allem im zaristischen Russ- Jaffa land. Die Einwanderung von Juden nach Palästina erhielt schon frühzeitig einen systematischen, organisatorischen Rahmen. Wichtigste Institution Lydda JORDANIEN Ramleh Ramallah wurde der 1901 gegründete Jüdische Nationalfond, der für die Anwerbung von Juden in aller Welt, für den Ankauf von Land in Palästina, meist von Jericho arabischen Großgrundbesitzern, und für die Zuteilung des Bodens an die Einwanderer zuständig war. -

229 the Onomasticon

229 THE ONOMASTICON. By Lieut.-Colonel CONDER, R.E., D.C.L. AMONG the more important authorities on Palestine geography is the Onomasticon of Eusebius, translated into Latin by Jerome. It has been used by me in the Memoirs of the Survey, but no continuous account of its contents, as illustrated by the Survey discoveries, has been publisheo by the Palestine Exploration Fund. The following notes may be useful as indicating its peculiar value. Jerome speaks of the nomenclature of the country in words which still apply sixteen centuries later: "Vocabnla qure vel eadem manent, vel immutata sunt postea, vel aliqua ex parte corrupta." His own acquaintance with Palestine was wide aud minute, and he often adds new details of interest to the Greek text of Eusebius which he renders. It is only necessary here to notice tile places which are fixed by the authors, and not those which were (and usually still are) unknown. The order of the names which follow is that of the Onomas ticon text, following the spelling of the Greek of Eusebius and the Gree],_ alphabet. Abarim, the Moab Mountains. Jerome says : "The name is still pointed out to those ascending from Livias (Tell er Rumeh) to Heshbon, near Mount Peor-retaining the original uame ; the region round being still called Phasga (Pisgah)." The road iu question appears to be that from Tell er Rameh to 'Aytln Mttsa (Ashdoth Pisgah), and thence to Heshbon, passing under N ebo on the north. Jerome calls Abarim "the mountain where Moses died," evidently N ebo itself ; but Peor (Phogor) seems to have been further south. -

Tel Dan ‒ Biblical Dan

Tel Dan ‒ Biblical Dan An Archaeological and Biblical Study of the City of Dan from the Iron Age II to the Hellenistic Period Merja Alanne Academic dissertation to be publicly discussed, by due permission of the Faculty of Theology, at the University of Helsinki in the Main Building, Auditorium XII on the 18th of March 2017, at 10 a.m. ISBN 978-951-51-3033-4 (paperback) ISBN 978-951-51-3034-1 (PDF) Unigrafia Helsinki 2017 “Tell el-Kadi” (Tel Dan) “Vettä, varjoja ja rehevää laidunta yllin kyllin ‒ mikä ihana levähdyspaikka! Täysin siemauksin olemme kaikki nauttineet kristallinkirkasta vettä lähteestä, joka on ’maailman suurimpia’, ja istumme teekannumme ympärillä mahtavan tammen juurella, jonne ei mikään auringon säde pääse kuumuutta tuomaan, sillä aikaa kuin hevosemme käyvät joen rannalla lihavaa ruohoa ahmimassa. Vaivumme niihin muistoihin, jotka kiertyvät levähdyspaikkamme ympäri.” ”Kävimme kumpua tarkastamassa ja huomasimme sen olevan mitä otollisimman kaivauksille. Se on soikeanmuotoinen, noin kilometrin pituinen ja 20 m korkuinen; peltona oleva pinta on hiukkasen kovera. … Tulimme ajatelleeksi sitä mahdollisuutta, että reunoja on kohottamassa maahan peittyneet kiinteät muinaisjäännökset, ehkä muinaiskaupungin muurit. Ei voi olla mitään epäilystä siitä, että kumpu kätkee poveensa muistomerkkejä vuosituhansia kestäneen historiansa varrelta.” ”Olimme kaikki yksimieliset siitä, että kiitollisempaa kaivauspaikkaa ei voine Palestiinassakaan toivoa. Rohkenin esittää sen ajatuksen, että tämä Pyhän maan pohjoisimmassa kolkassa oleva rauniokumpu -

Qedem 59, 60, 61 (2020) Amihai Mazar and Nava Panitz-Cohen

QEDEM 59, 60, 61 (2020) AMIHAI MAZAR AND NAVA PANITZ-COHEN Tel Reḥov, A Bronze and Iron Age City in the Beth-Shean Valley Volume I. Introductions, Synthesis and Excavations on the Upper Mound (Qedem 59) (XXIX+415 pp.). ISBN 978-965-92825-0-0 Tel Reḥov, A Bronze and Iron Age City in the Beth-Shean Valley Volume II, The Lower Mound: Area C and the Apiary (Qedem 60) (XVIII+658 pp.). ISBN 978-965-92825-1-7 Tel Reḥov, A Bronze and Iron Age City in the Beth-Shean Valley Volume III, The Lower Mound: Areas D, E, F and G (Qedem 61) (XVIII+465 pp.). ISBN 978-965-92825-2-4 Excavations at Tel Reḥov, carried out from 1997 to 2012 under the direction of Amihai Mazar on behalf of the Institute of Archaeology of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, revealed significant remains from the Early Bronze, Late Bronze and Iron Ages. The most prominent period is Iron Age IIA (10th–9th centuries BCE). The rich and varied architectural remains and finds from this period, including the unique apiary, an open-air sanctuary and an exceptional insula of buildings, make Tel Rehov a key site for understanding this significant period in northern Israel. These three volumes are the first to be published of the five that comprise the final report of the excavations at Tel Rehov. Volume I (Qedem 59) includes chapters on the environment, geology and historical geography of the site, as well as an introduction to the excavation project, a comprehensive overview and synthesis, as well as the stratigraphy and architecture of the excavation areas on the upper mound: Areas A, B and J, accompanied by pottery figures arranged by strata and contexts. -

Ancient DNA and Population Turnover in Southern Levantine Pigs

OPEN Ancient DNA and Population Turnover in SUBJECT AREAS: Southern Levantine Pigs- Signature of the EVOLUTIONARY BIOLOGY Sea Peoples Migration? PHYLOGENETICS Meirav Meiri1,2, Dorothee Huchon2, Guy Bar-Oz3, Elisabetta Boaretto4, Liora Kolska Horwitz5, Aren Maeir6, ZOOLOGY Lidar Sapir-Hen1, Greger Larson7, Steve Weiner8 & Israel Finkelstein1 ARCHAEOLOGY 1Institute of Archaeology, Tel Aviv University, Tel Aviv 69978, Israel, 2Department of Zoology, Tel Aviv University, Tel Aviv 69978, Received 3 4 30 May 2013 Israel, Department of Archaeology, University of Haifa, Haifa 31905, Israel, Weizmann Institute-Max Planck Center for Integrative Archaeology, D-REAMS Radiocarbon Dating Laboratory, Weizmann Institute of Science, Rehovot 76100, Israel, 5National Natural Accepted History Collections, Faculty of Life Science, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Jerusalem 91905, Israel, 6The Institute of 23 July 2013 Archaeology, The Martin (Szusz) Department of Land of Israel Studies and Archaeology, Bar-Ilan University, Ramat Gan 52900, Israel, 7Durham Evolution and Ancient DNA, Department of Archaeology, University of Durham, Durham DH1 3LE, United Kingdom, Published 8Kimmel Center for Archaeological Science, Department of Structural Biology, Weizmann Institute of Science, Rehovot 76100, 24 October 2013 Israel. Correspondence and Near Eastern wild boars possess a characteristic DNA signature. Unexpectedly, wild boars from Israel have requests for materials the DNA sequences of European wild boars and domestic pigs. To understand how this anomaly evolved, we sequenced DNA from ancient and modern Israeli pigs. Pigs from Late Bronze Age (until ca. 1150 BCE) Israel should be addressed to shared haplotypes of modern and ancient Near Eastern pigs. European haplotypes became dominant M.M. (meirav.meiri@ only during the Iron Age (ca. -

Zerohack Zer0pwn Youranonnews Yevgeniy Anikin Yes Men

Zerohack Zer0Pwn YourAnonNews Yevgeniy Anikin Yes Men YamaTough Xtreme x-Leader xenu xen0nymous www.oem.com.mx www.nytimes.com/pages/world/asia/index.html www.informador.com.mx www.futuregov.asia www.cronica.com.mx www.asiapacificsecuritymagazine.com Worm Wolfy Withdrawal* WillyFoReal Wikileaks IRC 88.80.16.13/9999 IRC Channel WikiLeaks WiiSpellWhy whitekidney Wells Fargo weed WallRoad w0rmware Vulnerability Vladislav Khorokhorin Visa Inc. Virus Virgin Islands "Viewpointe Archive Services, LLC" Versability Verizon Venezuela Vegas Vatican City USB US Trust US Bankcorp Uruguay Uran0n unusedcrayon United Kingdom UnicormCr3w unfittoprint unelected.org UndisclosedAnon Ukraine UGNazi ua_musti_1905 U.S. Bankcorp TYLER Turkey trosec113 Trojan Horse Trojan Trivette TriCk Tribalzer0 Transnistria transaction Traitor traffic court Tradecraft Trade Secrets "Total System Services, Inc." Topiary Top Secret Tom Stracener TibitXimer Thumb Drive Thomson Reuters TheWikiBoat thepeoplescause the_infecti0n The Unknowns The UnderTaker The Syrian electronic army The Jokerhack Thailand ThaCosmo th3j35t3r testeux1 TEST Telecomix TehWongZ Teddy Bigglesworth TeaMp0isoN TeamHav0k Team Ghost Shell Team Digi7al tdl4 taxes TARP tango down Tampa Tammy Shapiro Taiwan Tabu T0x1c t0wN T.A.R.P. Syrian Electronic Army syndiv Symantec Corporation Switzerland Swingers Club SWIFT Sweden Swan SwaggSec Swagg Security "SunGard Data Systems, Inc." Stuxnet Stringer Streamroller Stole* Sterlok SteelAnne st0rm SQLi Spyware Spying Spydevilz Spy Camera Sposed Spook Spoofing Splendide -

Israel in Figures”, Which Covers a Broad Range of Topics Related Affiliated with the Prime Minister’S to Israeli Demography, Society, and Economy

הלשכה המרכזית לסטטיסטיקה מדינת ישראל STATE OF ISRAEL Central Bureau of Statistics ΔϳΰϛήϤϟ ˯ΎμΣϹ ΓήΩ 2011 IIsrael INsr FIGURESael Introduction 3 The State of Israel 4 Key Figures 6 Climate 8 Environment 9 Population 10 Vital Statistics (live births, deaths, marriages, divorces) 11 Households and Families 12 Society and Welfare 13 Education 14 Health 15 Labour 16 Wages 17 National Economy 18 Government 19 Balance of Payments and Foreign Trade 20 Construction, Electricity and Water 21 Manufacturing, Commerce and Services 22 Science and Technology 23 Transport and Communications 24 Tourism 25 Agriculture 26 INTRODUCTION ABOUT THE CBS The Central Bureau of Statistics [CBS] is pleased to present the public with The CBS is an independent unit the booklet “Israel in Figures”, which covers a broad range of topics related affiliated with the Prime Minister’s to Israeli demography, society, and economy. Office. It operates in accordance with Statistical Order (new version) 1972, The booklet provides a brief summary of data on Israel. In this limited format, and is responsible for the official many topics could not be covered. statistics of Israel. The data presented here are updated to 2010, unless otherwise stated. The mission of the CBS is to Some of the figures are rounded. provide updated, high quality, and independent statistical information for For more comprehensive information about the country, including detailed a wide variety of users in Israel and definitions and explanations related to a broad range of topics, please refer abroad. to the Statistical Abstract of Israel No. 62, 2011 and the CBS website (www.cbs.gov.il) and other CBS publications that deal specifically with the The clientele of the CBS include topic in question. -

Distr. GENERAL S/8818 1

Distr. GENERAL S/8818 1)' September 1968 ORIGINAL: ENGLISH r LETTER DATED 17 SEPTEMBER1968 FROM THE PERMANENT REPRESENTATIVE OF ISRAEL ADDRESSEDTO THE PRESIDENT OF THE SECURITY COUNCIL On instructions from my Government, I have the honour to refer to my letter of 26 August 1968 (S/8774.) concerning repeated violations of the cease-fire by Jordan and to draw your attention to the continuation and intensification of military attacks from Jordanian territory against Israel since that date, Yesterday, 16 September, at approximately 1000 hours local time, Jordanian forces on the East Bank of the Jordan opened mortar and small arms fire on Israeli forces near Maoz Haim in the Beit Shean Valley. One Israeli soldier was killed and three were wounded. Fire was returned in self-defence. During the night the town of Beit Shean itself was shelled by 130 mm rockets fired from the East Bank of the Jordan. These rockets, of Czechoslovakian manufacture, are standard equipment in Arab armies. As a result of this attack, eight civilians were wounded, The Israel forces fired back on targets across the border from Beit Shean, in the Irbid area. Again, last night, at 2345 hours, artillery and mortar fire was opened on Israeli forces on the West Bank near the Allenby Bridge, from Jordanian territory on the East Bank of the Jordan. Fire was returned in self-defence and the exchange continued until 0300 this morning. These recent incidents follow a series of grave Jordanian violations of the cease-fire during the last three weeks , particulars of the more serious of which are contained in the attached list.