Open Access (.Pdf)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sky Italia 1 Sky Italia

Sky Italia 1 Sky Italia Sky Italia S.r.l. Nazione Italia Tipologia Società a responsabilità limitata Fondazione 31 luglio 2003 Fondata da Rupert Murdoch Sede principale Milano, Roma Gruppo News Corporation Persone chiave • James Murdoch: Presidente • Andrea Zappia: Amministratore Delegato • Andrea Scrosati: Vicepresidente Settore Media Prodotti Pay TV [1] Fatturato 2,740 miliardi di € (2010) [1] Risultato operativo 176 milioni di € (2010) [2] Utile netto 439 milioni di € (2009) Dipendenti 5000 (2011) Slogan Liberi di... [3] Sito web www.sky.it Sky Italia S.r.l. è la piattaforma televisiva digitale italiana del gruppo News Corporation, nata il 31 Luglio 2003 dall’operazione di concentrazione che ha coinvolto le due precedenti piattaforme Stream TV e Telepiù. Sky svolge la propria attività nel settore delle Pay TV via satellite, offrendo ai propri abbonati una serie di servizi, anche interattivi, accessibili previa installazione di una parabola satellitare, mediante un ricevitore di decodifica del segnale ed una smart card, abilitata alla visione dei contenuti diffusi da Sky. Sky viene diffusa agli utenti via satellite dalla flotta di satelliti Hot Bird posizionata a 13° est (i satelliti normalmente utilizzati per i servizi televisivi destinati all'Italia) e via cavo con le piattaforme televisive commerciali IPTV: TV di Fastweb, IPTV di Telecom Italia e Infostrada TV. Sky Italia 2 Storia • 2003 • Marzo: la Commissione europea autorizza la fusione tra TELE+ e Stream, da cui nasce Sky Italia. • Luglio: il 31 luglio Sky Italia inizia ufficialmente a trasmettere. • 2004 • Aprile: Sky abbandona il sistema di codifica SECA per passare all'NDS, gestito da News Corporation. -

Important Notice

IMPORTANT NOTICE THIS OFFERING IS AVAILABLE ONLY TO INVESTORS WHO ARE NON-U.S. PERSONS (AS DEFINED IN REGULATION S UNDER THE UNITED STATES SECURITIES ACT OF 1933 (THE “SECURITIES ACT”) (“REGULATION S”)) LOCATED OUTSIDE OF THE UNITED STATES. IMPORTANT: You must read the following before continuing. The following applies to the attached document (the “document”) and you are therefore advised to read this carefully before reading, accessing or making any other use of the document. In accessing the document, you agree to be bound by the following terms and conditions, including any modifications to them any time you receive any information from Sky plc (formerly known as British Sky Broadcasting Group plc) (the “Issuer”), Sky Group Finance plc (formerly known as BSkyB Finance UK plc), Sky UK Limited (formerly known as British Sky Broadcasting Limited), Sky Subscribers Services Limited or Sky Telecommunications Services Limited (formerly known as BSkyB Telecommunications Services Limited) (together, the “Guarantors”) or Barclays Bank PLC or Société Générale (together, the “Joint Lead Managers”) as a result of such access. NOTHING IN THIS ELECTRONIC TRANSMISSION CONSTITUTES AN OFFER OF SECURITIES FOR SALE IN THE UNITED STATES OR ANY OTHER JURISDICTION WHERE IT IS UNLAWFUL TO DO SO. THE SECURITIES AND THE GUARANTEES HAVE NOT BEEN, AND WILL NOT BE, REGISTERED UNDER THE SECURITIES ACT, OR THE SECURITIES LAWS OF ANY STATE OF THE UNITED STATES OR OTHER JURISDICTION AND THE SECURITIES AND THE GUARANTEES MAY NOT BE OFFERED OR SOLD, DIRECTLY OR INDIRECTLY, WITHIN THE UNITED STATES OR TO, OR FOR THE ACCOUNT OR BENEFIT OF, U.S. -

Download Our Documentary 2017/2022

Entertain your brain 2021-2022 DOCUMENTARY CATALOGUE Nexo Digital Entertain your Brain A leading player in international sales and distribution of cinematic documentaries and 4k native con- tents to portray Art, narrate History and experience Music pop icons and Sport legends. Since 2017 we are also involved in production. Nexo+ is the newest art & culture OTT platform to entertain your brain. Our catalogue also includes Stories to tell of Disability and Inclusion, Expedition one-offs specials as well as mini factual series. Nexo Digital has also been producing cinematic documentaries with important partners like The Hermitage, The Prado, The Vatican Museums, The Uffizi Gallery - prestigious mu- seums, important exhibitions - stories narrated by Oscar winners such as Jeremy Irons and Helen Mirren. SERIES DELIVERY: SPRING 2022 PILOT AVAILABLE: JULY 2021 The Grand Egyptian Museum Collection A brand new original 13x 26’ series on the collections from the biggest Archaeological Museum in the World to be inaugurated in 2022 NEXO DIGITAL KICKS OFF PRESALES MOOD TEASER >> EGYPT NEW NEW NEW YESTERDAY AND TOMORROW INDEX >> 1 TUTANKHAMUN ONCE UPON A TIME ROOTS OF EGYPT THE THROBBING RED SEA THE EGYPTIAN THE LAST EXHIBITION IN EGYPT SERIES DESERT THE HERITAGE OF THE PHARAOHS SERIES ICONS TO NEW NEW NEW DISABILITY NEW NEW CELEBRATE AND >> INCLUSION >> FRIDA MARIA MONTESSORI FREUD 2.0 PELÉ FERRARI 312B ROBERTO BOLLE BECAUSE OF MY DON’T BE AFRAID IF VIVA LA VIDA THE VISIONARY THE LAST SHOW WHERE THE THE ART OF DANCE BODY I HUG YOU EDUCATOR REVOLUTION -

UPDATED Activate Outlook 2021 FINAL DISTRIBUTION Dec

ACTIVATE TECHNOLOGY & MEDIA OUTLOOK 2021 www.activate.com Activate growth. Own the future. Technology. Internet. Media. Entertainment. These are the industries we’ve shaped, but the future is where we live. Activate Consulting helps technology and media companies drive revenue growth, identify new strategic opportunities, and position their businesses for the future. As the leading management consulting firm for these industries, we know what success looks like because we’ve helped our clients achieve it in the key areas that will impact their top and bottom lines: • Strategy • Go-to-market • Digital strategy • Marketing optimization • Strategic due diligence • Salesforce activation • M&A-led growth • Pricing Together, we can help you grow faster than the market and smarter than the competition. GET IN TOUCH: www.activate.com Michael J. Wolf Seref Turkmenoglu New York [email protected] [email protected] 212 316 4444 12 Takeaways from the Activate Technology & Media Outlook 2021 Time and Attention: The entire growth curve for consumer time spent with technology and media has shifted upwards and will be sustained at a higher level than ever before, opening up new opportunities. Video Games: Gaming is the new technology paradigm as most digital activities (e.g. search, social, shopping, live events) will increasingly take place inside of gaming. All of the major technology platforms will expand their presence in the gaming stack, leading to a new wave of mergers and technology investments. AR/VR: Augmented reality and virtual reality are on the verge of widespread adoption as headset sales take off and use cases expand beyond gaming into other consumer digital activities and enterprise functionality. -

Sky Chooses Vizrt for Stereo 3D Channel

Sky Chooses Vizrt for Stereo 3D Channel Bergen, Norway, March 23, 2010. Vizrt Ltd. (Oslo Main List: VIZ) Sky Sports today announced that it has chosen Vizrt as the core graphics platform for its 3DTV channel, due to launch in April. Darren Long, Sky Sports’ Director of Operations described his reasons for the decision, “We have worked with Vizrt for more than ten years. They have supported us with excellent graphics for our SD sports coverage, then later for HD and now they will do so again for 3D. Vizrt has always been a real-time 3D system and this meant it was easy for our designers to convert Sky Sports’ current HD designs to their stereo 3D equivalents. The results are stunning and the graphics drew special attention from viewers when we recently ran our world’s first stereo 3D football match trial. I am sure that Vizrt’s graphics will enhance our new 3D channel, just as they do for all our other channels.” The stereoscopic Vizrt system uses a Viz Trio CG operator interface, controlling a Viz render engine PC. This powerful graphics engine uses two graphics cards and the separately rendered HD channels for each eye are synchronised by a new application developed for the process. The stereoscopic convergence point and depth are also adjustable on the fly to allow for changing camera views. The system can also be driven by GPI triggers from the vision- mixing desk. Vizrt UK’s Managing Director, Rex Jenkins added, “Sky Sports demands the highest quality from its graphics systems and we are glad to meet their needs. -

Conference Faculty Jason Adler

Conference Faculty Jason Adler...................................................................................................................................... 1 Mark A. Cohen................................................................................................................................ 2 Hon. Linda Kuczma ........................................................................................................................ 3 Hon. Pauline Newman .................................................................................................................... 4 Carlos Aboim .................................................................................................................................. 5 Kenneth R. Adamo.......................................................................................................................... 6 Themi Anagnos ............................................................................................................................... 7 Ian Ballon ........................................................................................................................................ 8 Patrick G. Burns .............................................................................................................................. 9 Christopher V. Carani ................................................................................................................... 10 Charisse Castagnoli ...................................................................................................................... -

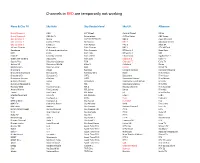

Channels in RED Are Temporarily Not Working

Channels in RED are temporarily not working Nova & Ote TV Sky Italy Sky Deutschland Sky UK Albanian Nova Cinema 1 AXN 13th Street Animal Planet 3 Plus Nova Cinema 2 AXN SciFi Boomerang At The Races ABC News Ote Cinema 1 Boing Cartoon Network BBC 1 Agon Channel Ote Cinema 2 Caccia e Pesca Discovery BBC 2 Albanian screen Ote Cinema 3 Canale 5 Film Action BBC 3 Alsat M Village Cinema Cartoonito Film Cinema BBC 4 ATV HDTurk Sundance CI Crime Investigation Film Comedy BT Sports 1 Bang Bang FOX Cielo Film Hits BT Sports 2 BBF FOXlife Comedy Central Film Select CBS Drama Big Brother 1 Greek VIP Cinema Discovery Film Star Channel 5 Club TV Sports Plus Discovery Science FOX Chelsea FC Cufo TV Action 24 Discovery World Kabel 1 Clubland Doma Motorvision Disney Junior Kika Colors Elrodi TV Discovery Dmax Nat Geo Comedy Central Explorer Shkence Discovery Showcase Eurosport 1 Nat Geo Wild Dave Film Aktion Discovery ID Eurosport 2 ORF1 Discovery Film Autor Discovery Science eXplora ORF2 Discovery History Film Drame History Channel Focus ProSieben Discovery Investigation Film Dy National Geographic Fox RTL Discovery Science Film Hits NatGeo Wild Fox Animation RTL 2 Disney Channel Film Komedi Animal Planet Fox Comedy RTL Crime Dmax Film Nje Travel Fox Crime RTL Nitro E4 Film Thriller E! Entertainment Fox Life RTL Passion Film 4 Folk+ TLC Fox Sport 1 SAT 1 Five Folklorit MTV Greece Fox Sport 2 Sky Action Five USA Fox MAD TV Gambero Rosso Sky Atlantic Gold Fox Crime MAD Hits History Sky Cinema History Channel Fox Life NOVA MAD Greekz Horror Channel Sky -

TT-2019-Versie 11

PROGRAM PROGRAM SUBJECT TO CHANGE FRIDAY JULY 12 FOR LATEST CHANGES, CHECK: WWW.NORTHSEAJAZZ.COM 15:00 15:30 16:00 16:30 17:00 17:30 18:00 18:30 19:00 19:30 20:00 20:30 21:00 21:30 22:00 22:30 23:00 23:30 00:00 00:30 AHOY OPEN: 14:30 BURT AMAZON DIANA KRALL BACHARACH GILBERTO GIL GARY BARTZ CHUCHO VALDES STEVE GADD BAND ANOTHER EARTH ORQUESTA AKOKÁN HUDSON featuring RAVI COLTRANE JAZZ BATÁ & CHARLES TOLLIVER CURTIS NILE HARDING RAG’N’BONEMAN JOE JACKSON TOWER OF POWER JOSÉ JAMES LEAN ON ME BLOOD ORANGE ANITA BAKER JACOB BANKS MAAS with NOORDPOOL ORKEST MAKAYA McCRAVEN ARTIST IN RESIDENCE BRAXTON COOK UNIVERSAL BEINGS ROBERT GLASPER THE INTERNET CONGO with BRANDEE YOUNGER with CHRIS DAVE, DERRICK HODGE and JOEL ROSS and special guest YASIIN BEY CONGO SON SWAGGA SON SWAGGA THEON CROSS THEON CROSS SQUARE VERSIE 11 - 26 JUNI 2019 15:00 15:30 16:00 16:30 17:00 17:30 18:00 18:30 19:00 19:30 20:00 20:30 21:00 21:30 22:00 22:30 23:00 23:30 00:00 00:30 JOHN ZORN PRESENTS BAGATELLES MARATHON featuring MASADA, SYLVIE COURVOISIER and MARK FELDMAN, MARY HALVORSON QUARTET, CRAIG TABORN, NIK BÄRTSCH’S DARLING TRIGGER, ERIK FRIEDLANDER and MIKE NICOLAS, JOHN MEDESKI TRIO, NOVA QUARTET, GYAN RILEY and JULIAN LAGE, RONIN BRIAN MARSELLA TRIO, IKUE MORI, KRIS DAVIS, PETER EVANS, ASMODEUS DAFNIS PRIETO RYMDEN CHRISTIAN SANDS BUGGE WESSELTOFT BEN WENDEL BOB REYNOLDS MADEIRA BIG BAND TRIO DAN BERGLUND, SEASONS BAND GROUP feat. -

71-Page White Paper

RESTRICTIVE PAPERLESS TICKETS A White Paper by the American Antitrust Institute ! By James D. Hurwitz Table of Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1 INTRODUCTION 4 PART I – INDUSTRY STRUCTURE AND OPERATION 8 A. Overview of the Ticketing Industry 8 1. The Primary Market 8 2. The Secondary Market 10 3. Financial Relationships 11 4. The Relationship Between Pricing in the Primary and Secondary Markets 12 B. Major Ticket Sellers 14 1. Primary Market Ticket Sellers 14 2. Secondary Market Ticket Sellers 17 C. Ticket Formats 19 1. Paper Tickets 19 2. E-Tickets 19 3. Paperless Tickets 19 4. Mobile Tickets 20 D. Categories of Paperless Tickets 21 1. Non-Transferable Paperless Tickets 21 2. Restrictive Paperless Tickets 22 3. Easily Transferable Paperless Tickets 23 2919 ELLICOTT ST, NW • WASHINGTON, DC 20008 PHONE: 202-276-6002 • FAX: 202-966-8711 • [email protected] www.antitrustinstitute.org E. New Developments 24 1. Dynamic Pricing 25 2. White Label Competition 26 3. Social Media 27 4. Discount Sellers 28 5. Other Technological and Marketing Changes 30 PART II – INJURY TO CONSUMERS 32 A. Limitations on Resale of Restrictive Paperless Tickets 33 1. Prohibition of Ticket Transfers 33 2. Requirement to Sell Only Through TicketExchange 33 3. Price Floors 34 4. Price Ceilings 35 5. Restraints on Season or Series Tickets 35 B. Limitations on Gifts or Donations of Restrictive Paperless Tickets 36 C. Limitations on Purchase and Use of Restrictive Paperless Tickets 37 D. Increased Risk for Purchasers of Restrictive Paperless Tickets 38 E. Violation of Reasonable Purchaser Expectations 39 PART III – HARM TO COMPETITION 40 A. -

Press Kit 2017

BIOGRAPHY BIOGRAPHY One of his generation’s extraordinary talents, Scott Tixier has made a name for himself as a violinist-composer of wide- ranging ambition, individuality and drive — “the future of jazz violin” in the words of Downbeat Magazine and “A remarkable improviser and a cunning jazz composer” in those of NPR. The New York City-based Tixier, born in 1986 in Montreuil, France has performed with some of the leading lights in jazz and music legends from Stevie Wonder to NEA jazz master Kenny Barron; as a leader as well. Tixier’s acclaimed Sunnyside album “Cosmic Adventure” saw the violinist performing with a all star band “taking the jazz world by storm” as the All About Jazz Journal put it. The Village Voice called the album “Poignant and Reflective” while The New York Times declared “Mr. Tixier is a violinist whose sonic palette, like his range of interests, runs open and wide; on his new album, “Cosmic Adventure,” he traces a line through chamber music, Afro-Cuban groove and modern jazz.” When JazzTimes said"Tixier has a remarkably vocal tone, and he employs it with considerable suspense. Cosmic Adventure is a fresh, thoroughly enjoyable recording!" Tixier studied classical violin at the conservatory in Paris. Following that, he studied improvisation as a self-educated jazz musician. He has been living in New York for over a decade where he performed and recorded with a wide range of artists, including, Stevie Wonder, Kenny Barron, John Legend, Ed Sheeran, Charnett Moffett, Cassandra Wilson, Chris Potter, Christina Aguilera, Common, Anthony Braxton, Joss Stone, Gladys Knight, Natalie Cole, Ariana Grande, Wayne Brady, Gerald Cleaver,Tigran Hamasyan and many more He played in all the major venues across the United States at Carnegie Hall, the Radio City Music Hall, Madison Square Garden, Barclays Center, Jazz at Lincoln Center, the Blue Note Jazz Club, the Apollo Theater, the Smalls Jazz Club, The Stone, Roulette, Joe's Pub, Prudential Center and the United States Capitol. -

US and Plaintiff States V. Ticketmaster and Live Nation

Case 1:10-cv-00139-RMC Document 13 Filed 06/21/10 Page 1 of 37 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, et al., Plaintiffs, v. Case: 1:10-cv-00139 Assigned to: Collyer, Rosemary M. Assign. Date: 1/25/2010 TICKETMASTER ENTERTAINMENT, Description: Antitrust INC., et al., Defendants. PLAINTIFF UNITED STATES’ RESPONSE TO PUBLIC COMMENTS Pursuant to the requirements of the Antitrust Procedures and Penalties Act, 15 U.S.C. § 16(b)-(h) (“APPA” or “Tunney Act”), the United States hereby files the public comments concerning the proposed Final Judgment in this case and the United States’ response to those comments. After careful consideration of the comments, the United States continues to believe that the proposed Final Judgment will provide an effective and appropriate remedy for the antitrust violations alleged in the Amended Complaint. The United States will move the Court, pursuant to 15 U.S.C. § 16(b)-(h), for entry of the proposed Final Judgment after the public comments and this Response have been published.1 1 As approved by the Court in a Minute Order dated June 15, 2010, the United States will publish the Response and the comments without attachments or exhibits in the Federal Register. The United States will post complete versions of the comments with attachments and exhibits on the Antitrust Division’s website at http://www.justice.gov/atr/cases/ticket.htm. -1- Case 1:10-cv-00139-RMC Document 13 Filed 06/21/10 Page 2 of 37 I. PROCEDURAL HISTORY On January 25, 2010, the United States and the States of Arizona, Arkansas, California, Florida, Illinois, Iowa, Louisiana, Nebraska, Nevada, Ohio, Oregon, Rhode Island, Tennessee, Texas, and Wisconsin, and the Commonwealths of Massachusetts and Pennsylvania (the “States”) filed the Complaint in this matter, alleging that the merger of Ticketmaster Entertainment, Inc. -

Gerry Hemingway Quartet Press Kit (W/Herb Robertson and Mark

Gerry Hemingway Quartet Herb Robertson - trumpet Ellery Eskelin - tenor saxophone Mark Dresser- bass Gerry Hemingway – drums "Like the tightest of early jazz bands, this crew is tight enough to hang way loose. *****" John Corbett, Downbeat Magazine Gerry Hemingway, who developed and maintained a highly acclaimed quintet for over ten years, has for the past six years been concentrating his experienced bandleading talent on a quartet formation. The quartet, formed in 1997 has now toured regularly in Europe and America including a tour in the spring of 1998 with over forty performances across the entire country. “What I experienced night after night while touring the US was that there was a very diverse audience interested in uncompromising jazz, from young teenagers with hard core leanings who were drawn to the musics energy and edge, to an older generation who could relate to the rhythmic power, clearly shaped melodies and the spirit of musical creation central to jazz’s tradition that informs the majority of what we perform.” “The percussionist’s expressionism keeps an astute perspective on dimension. He can make you think that hyperactivity is accomplished with a hush. His foursome recently did what only a handful of indie jazzers do: barnstormed the U.S., drumming up business for emotional abstraction and elaborate interplay . That’s something ElIery Eskelin, Mark Dresser and Ray Anderson know all about.“ Jim Macnie Village Voice 10/98 "The Quartet played the compositions, stuffed with polyrhythms and counterpoints, with a swinging