Bank Portfolio Allocation: Evidence from Sierra Leone

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BTI 2020 Country Report — Sierra Leone

BTI 2020 Country Report Sierra Leone This report is part of the Bertelsmann Stiftung’s Transformation Index (BTI) 2020. It covers the period from February 1, 2017 to January 31, 2019. The BTI assesses the transformation toward democracy and a market economy as well as the quality of governance in 137 countries. More on the BTI at https://www.bti-project.org. Please cite as follows: Bertelsmann Stiftung, BTI 2020 Country Report — Sierra Leone. Gütersloh: Bertelsmann Stiftung, 2020. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Contact Bertelsmann Stiftung Carl-Bertelsmann-Strasse 256 33111 Gütersloh Germany Sabine Donner Phone +49 5241 81 81501 [email protected] Hauke Hartmann Phone +49 5241 81 81389 [email protected] Robert Schwarz Phone +49 5241 81 81402 [email protected] Sabine Steinkamp Phone +49 5241 81 81507 [email protected] BTI 2020 | Sierra Leone 3 Key Indicators Population M 7.7 HDI 0.438 GDP p.c., PPP $ 1604 Pop. growth1 % p.a. 2.1 HDI rank of 189 181 Gini Index 34.0 Life expectancy years 53.9 UN Education Index 0.403 Poverty3 % 81.3 Urban population % 42.1 Gender inequality2 0.644 Aid per capita $ 71.8 Sources (as of December 2019): The World Bank, World Development Indicators 2019 | UNDP, Human Development Report 2019. Footnotes: (1) Average annual growth rate. (2) Gender Inequality Index (GII). (3) Percentage of population living on less than $3.20 a day at 2011 international prices. Executive Summary General elections were held in Sierra Leone in March 2018 to elect the president, parliament and local councils. -

Banking Sector Liberalisation in Uganda Process, Results and Policy Options

Banking Sector Liberalisation in Uganda Process, Results and Policy Options Research report Editors: Madhyam & SOMO December 2010 Banking Sector Liberalisation in Uganda Process, Results and Policy Options Research report By: Lawrence Bategeka & Luka Jovita Okumu (Economic Policy Research Centre, Uganda) Editors: Kavaljit Singh (Madhyam), Myriam Vander Stichele (SOMO) December 2010 SOMO is an independent research organisation. In 1973, SOMO was founded to provide civil society organizations with knowledge on the structure and organisation of multinationals by conducting independent research. SOMO has built up considerable expertise in among others the following areas: corporate accountability, financial and trade regulation and the position of developing countries regarding the financial industry and trade agreements. Furthermore, SOMO has built up knowledge of many different business fields by conducting sector studies. 2 Banking Sector Liberalisation in Uganda Process, Results and Policy Options Colophon Banking Sector Liberalisation in Uganda: Process, Results and Policy Options Research report December 2010 Authors: Lawrence Bategeka and Luka Jovita Okumu (EPRC) Editors: Kavaljit Singh (Madhyam) and Myriam Vander Stichele (SOMO) Layout design: Annelies Vlasblom ISBN: 978-90-71284-76-2 Financed by: This publication has been produced with the financial assistance of the Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs. The contents of this publication are the sole responsibility of SOMO and the authors, and can under no circumstances be regarded as reflecting the position of the Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Published by: Stichting Onderzoek Multinationale Ondernemingen Centre for Research on Multinational Corporations Sarphatistraat 30 1018 GL Amsterdam The Netherlands Tel: + 31 (20) 6391291 Fax: + 31 (20) 6391321 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.somo.nl Madhyam 142 Maitri Apartments, Plot No. -

World Bank Document

THE GAMBIA: Policies to Foster Growth Public Disclosure Authorized Volume II. Macroeconomy, Finance, Trade and Energy May 19, 2015 Trade and Competitiveness Practice Cape Verde, Gambia, Guinea-Bissau, Mauritania and Senegal Country Department Africa Region Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Document of the World Bank REPUBLIC OF GAMBIA –FISCAL YEAR January 1 st - December 31 st MONETARY EQUIVALENT (Exchange rate as of May 15, 2015) Currency Unit = Gambian Dalasi (GMD) 1,00 US$ = 42.6000 GMD WEIGHTS AND MEASUREMENTS Metric System ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS ABTA Association of British Travel Agents IPC Investment Promotion Center TEU Twenty-foot equivalent Unit ADR Average Daily Rate JIC Joint Industrial Council Agreement TFP Total Factor Productivity Agribusiness Services and Producers’ Trade Intensity Index ASPA LDCs Least Developed countries TII Association Association of Small Enterprises in Tourism Master Plan ASSET LFO Liquid Pilot Fuel TMP Tourism C.Pct Column Percentage LIC Low Income Countries ULC Unit Labor Cost CAR Capital Adequacy ratio LMIC Low Middle Income Countries UNDP United Nations Development Program CBG Central Bank of The Gambia MFI Microfinance institution UREP Upland Rice Expansion Program Ministry of Finance and Economic United Nations World Tourism CET Common external tariff MOFEA UNWTO Affairs Organization DB 2015 Doing business 2015 Report MTC Ministry of Tourism and Culture VFR Visiting Friends and Relatives Economic Community of West Ministry of Trade, Industry -

Liberia's 9 Commercial Banks

Public Disclosure Authorized IFC Mobile Money Scoping Country Report: Liberia Public Disclosure Authorized June, 2012 Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized About The MasterCard Foundation Program IFC and the MasterCard Foundation (MCF) entered into a partnership focused on accelerating the growth and outreach of microfinance and mobile financial services in Sub-Saharan Africa. The partnership aims to leverage IFC’s expanding microfinance client network in the region and its emerging expertise in mobile financial services to catalyze innovative and low-cost approaches for expanding financial services to low- income populations. The Partnership has three Primary Components Mobile Financial Service IFC and The MasterCard Foundation see tremendous opportunity with Microfinance mobile banking, particularly for those living in rural areas. Mobile phones Through this partnership, IFC will result in lower transactions costs and implement a scaling program for reduce the cost of information. This Knowledge & Learning microfinance in Africa. The primary partnership will (i) identify nascent This partnership will include a major purpose of the Program is to markets to accelerate the uptake of knowledge sharing component to accelerate delivery of financial branchless banking services, (ii) work ensure broader dissemination of services in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) with private sector players to build results, impacts and lessons learned through the significant scaling up of expertise and infrastructure to from both the microfinance and between eight and ten of IFC‘s sustainably offer financial services to mobile financial services. These strongest microfinance partners in the unbanked using mobile knowledge products will include Africa. Interventions will include technology and agent networks and product and channel diversification (iii) build robust business models that into underserved areas. -

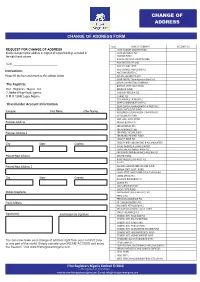

Backup of Change of Address

CHANGE OF ADDRESS CHANGE OF ADDRESS FORM TICK NAME OF COMPANY ACCOUNT NO. REQUEST FOR CHANGE OF ADDRESS ACAP CANARY GROWTH FUND Kindly change my/our address in respect of my/ourholdings as ticked in AFRICAN PAINTS PLC the right hand column ANCHOR FUND ARM AGGRESSIVE GROWTH FUND Date: _____________________________ ARM DISCOVERY FUND ARM ETHICAL FUND ASO-SAVINGS AND LOANS PLC Instructions ABC TRANSPORT PLC Please fill the form and return to the address below AUSTIN LAZ AND CO. PLC BANK PHB PLC (Now Keystone Bank Ltd) The Registrar, BCN PLC-MARKETING COMPANY BAYELSA STATE GOVT BOND First Registrars Nigeria Ltd. BEDROCK FUND 2, Abebe Village Road, Iganmu CADBURY NIGERIA PLC P. M. B. 12692 Lagos. Nigeria. CHAMS PLC COSTAIN WEST AFRICA PLC Shareholder Account Information DAAR COMMUNICATIONS PLC DEAP CAPITAL MANAGEMENT & TRUST PLC DELTA STATE GOVT BOND Surname First Name Other Names REDEEMED GLOBAL MEDIA COMPANY LTD DV BALANCED FUND EDO STATE GOVT. BOND Previous Address FAMAD NIGERIA PLC FBN HOLDINGS PLC FBN HERITAGE FUND Previous Address 2 FBN FIXED INCOME FUND FBN MONEY MARKET FUND FIDELITY BANK PLC City State Country FIDELITY NIGFUND (INCOME & ACCUMULATED) FOKAS SAVINGS & LOANS LIMITED FORTIS MICROFINANCE BANK PLC FRIESLANDCAMPINA WAMCO NIGERIA PLC Present\New Address GTBANK BOND HONEYWELL FLOUR MILLS PLC JULI PLC Present\New Address 2 KAKAWA GUARANTEED INCOME FUND KWARA STATE GOVT. BOND LAGOS STATE GOVT. BOND (1st & 2nd tranche) LEARN AFRICA PLC City State Country NIGERIAN BREWERIES PLC OANDO PLC OASIS INSURANCE PLC ONDO STATE BOND Mobile -

The West Indian Mission to West Africa: the Rio Pongas Mission, 1850-1963

The West Indian Mission to West Africa: The Rio Pongas Mission, 1850-1963 by Bakary Gibba A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Department of History University of Toronto © Copyright by Bakary Gibba (2011) The West Indian Mission to West Africa: The Rio Pongas Mission, 1850-1963 Doctor of Philosophy, 2011 Bakary Gibba Department of History, University of Toronto Abstract This thesis investigates the efforts of the West Indian Church to establish and run a fascinating Mission in an area of West Africa already influenced by Islam or traditional religion. It focuses mainly on the Pongas Mission’s efforts to spread the Gospel but also discusses its missionary hierarchy during the formative years in the Pongas Country between 1855 and 1863, and the period between 1863 and 1873, when efforts were made to consolidate the Mission under black control and supervision. Between 1873 and 1900 when additional Sierra Leonean assistants were hired, relations between them and African-descended West Indian missionaries, as well as between these missionaries and their Eurafrican host chiefs, deteriorated. More efforts were made to consolidate the Pongas Mission amidst greater financial difficulties and increased French influence and restrictive measures against it between 1860 and 1935. These followed an earlier prejudiced policy in the Mission that was strongly influenced by the hierarchical nature of nineteenth-century Barbadian society, which was abandoned only after successive deaths -

Sierra Leone - Mobile Money Transfer Market Study

Sierra Leone - Mobile Money Transfer Market Study FINAL REPORT, March 2013 March 2013 Report prepared by PHB Development, with the support of Disclaimer The contents of this report are the responsibility of PHB Development and do not necessarily reflect the views of Cordaid. The information contained in this report and any errors or mistakes that occurred are the sole responsibility of PHB Development. 2 Contents Introduction………………………………………………………………………………3 Executive Summary and Recommendations………………………………............... 9 I. Module 1 Regulation and Partnerships (Supply side)……………………………….23 II. Module 2 Markets and products (Demand side )……………………………………..56 III. Module 3 Distribution Networks………………………………………………………..74 IV. Module 4 MFI Internal Capacity………………………………………………………..95 V. Module 5 Scenario's for Mobile Money Transfers and the MFIs in Sierra Leone...99 3 Introduction Cordaid has invited PHB Development to execute a market study on Mobile Money Transfers (MMT) in Sierra Leone and on the opportunities this market offers for Microfinance Institutions (MFIs). This study follows on the MITAF1 programme that Cordaid co-financed in the period 2004-2011. The results of the market study were shared in an interactive workshop in Sierra Leone on 26 February 2013. 27 persons attended, representing MFIs, MMT providers, the Bank of Sierra Leone and the donor. This final report represents an overview of the information collected, on which the workshop has been based. Moreover, information obtained during the workshop is reflected in this document. In addition, the MFIs have received individual assessment reports on their readiness for MMT. This report starts with an executive summary followed by recommendations for the MFIs and Cordaid. Chapters 1-5 provide detailed information on the regulation and the supply side of market players and MMT partnerships (module 1), on the demand for financial products (module 2) and the agent networks in Sierra Leone (module 3). -

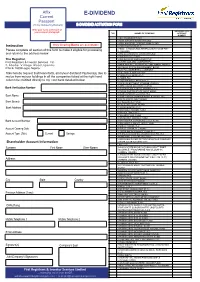

E-Dividend Mandate Activation Form of First Registrars

Affix E-DIVIDEND Current Passport (To be stamped by Bankers) E-DIVIDEND ACTIVATION FORM Write your name at the back of your passport photograph SHAREHOLER’S TICK NAMES OF COMPANY ACCOUNT NUMBER ABC TRANSPORT PLC ACAP CANARY GROWTH FUND AFRICAN DEVELOPMENT BANK BOND Instruction Only Clearing Banks are acceptable AFRICAN PAINTS PLC ASSET & RESOURCE MANAGEMENT COMPANY Please complete all section of this form to make it eligible for processing LTD(FUND) and return to the address below ARM AGGRESSIVE GROWTH FUND ARM ETHICAL FUND The Registrar, ASO-SAVINGS AND LOANS PLC First Registrars & Investor Services Ltd. AUSTIN LAZ AND COMPANY PLC 2 , A b e b e V i l l a g e R o a d , I g a n m u BANK PHB PLC (NOW KEYSTONE BANK LIMITED) P. M. B. 12692 Lagos. Nigeria. BAYELSA STATE GOVERNMENT BOND BCN PLC-MARKETING COMPANY I\We hereby request that henceforth, all my\our dividend Payment(s) due to BOC GASES NIGERIA PLC CADBURY NIGERIA PLC me\us from my\our holdings in all the companies ticked at the right hand CHAMS PLC column be credited directly to my \ our bank detailed below: COSTAIN WEST AFRICA PLC CORE INVESTMENT SCHEME (COINS) CORE VALUE ACCOUNT (COVA) Bank Verification Number CR SERVICES (CREDIT BUREAU) PLC CROSS RIVERS STATE GOVT BOND DAAR COMMUNICATIONS PLC Bank Name DEAP CAPITAL MANAGEMENT & TRUST PLC DELTA STATE GOVT BOND Bank Branch DV BALANCED FUND EDO STATE GOVT BOND Bank Address FAMAD NIGERIA PLC FBN FIXED INCOME FUND FBN HOLDINGS PLC FBN HERITAGE FUND FBN MONEY MARKET FUND Bank Account Number FBN NIGERIA EUROBOND (USD) FUND FBN NIGERIA -

World Bank Group's Travel Per Diem Rates for Official Bank Use Only

MTV World Bank Group's Travel Per Diem Rates (Per Diem USD) For Official Bank Use Only - Not for circulation Country Code City Code Country City Name 2012 AF BIN AFGHANISTAN BAMIYAN 53.00 AF HEA AFGHANISTAN HERAT 47.00 AF JAA AFGHANISTAN JALALABAD 45.00 AF KBL AFGHANISTAN KABUL 85.00 AF KDH AFGHANISTAN KANDAHAR 48.00 AF MZR AFGHANISTAN MAZAR-I-SHARI 47.00 AF XXX AFGHANISTAN OTHER OR UNKNOWN CITY 50.00 AL DU9 ALBANIA DURRES -ALBANIA 56.00 AL EB9 ALBANIA ELBASAN - ALBANIA 43.00 AL FI9 ALBANIA FIER 43.00 AL KC9 ALBANIA KORCA 43.00 AL KU9 ALBANIA KUKES 43.00 AL XXX ALBANIA OTHER OR UNKNOWN CITY 47.00 AL SA9 ALBANIA SARANDA 84.00 AL TIA ALBANIA TIRANA 104.00 AL VL9 ALBANIA VLORE 57.00 DZ ALG ALGERIA ALGIERS 145.00 DZ AAE ALGERIA ANNABA 98.00 DZ GHA ALGERIA GHARDAIA 72.00 DZ ORN ALGERIA ORAN 83.00 DZ XXX ALGERIA OTHER OR UNKNOWN CITY 71.00 DZ TID ALGERIA TIARET 73.00 DZ TLM ALGERIA TLEMCEN 73.00 VI XXX AMER.VIRGIN IS. OTHER OR UNKNOWN CITY 68.00 AD XXX ANDORRA OTHER OR UNKNOWN CITY 120.00 AO BUG ANGOLA BENGUELA 101.00 AO CAB ANGOLA CABINDA 107.00 AO LAD ANGOLA LUANDA 118.00 AO SDD ANGOLA LUBANGO 108.00 AO XXX ANGOLA OTHER OR UNKNOWN CITY 91.00 AI XXX ANGUILLA OTHER OR UNKNOWN CITY 100.00 AG ANU ANTIGUA/BARBUDA ANTIGUA 109.00 AG XXX ANTIGUA/BARBUDA OTHER OR UNKNOWN CITY 105.00 AR BHI ARGENTINA BAHIA BLANCA 69.00 AR BUE ARGENTINA BUENOS AIRES 100.00 AR CTC ARGENTINA CATAMARCA 69.00 AR CRD ARGENTINA COMODORO RIVA 69.00 AR COR ARGENTINA CORDOBA 90.00 AR CNQ ARGENTINA CORRIENTES 66.00 AR EQS ARGENTINA ESQUEL 69.00 AR FMA ARGENTINA FORMOSA 69.00 -

Sierra Leone, the Constraints Analysis Would Be Concerned with What Is Preventing the Country from Achieving Broad-Based Economic Growth

The production of the constraints analyses posted on this website was led by the partner governments, and was used in the development of a Millennium Challenge Compact or threshold program. Although the preparation of the constraints analysis is a collaborative process, posting of the constraints analyses on this website does not constitute an endorsement by MCC of the content presented therein. 2014-001-1569-02 Republic of Sierra Leone SIERRA LEONE CONSTRAINTS ANALYSIS REPORT: A Diagnostic Study of the Sierra Leone Economy; Identifying Binding Constraints to Private Investments and Broad-based Growth FINAL REPORT An Analysis Prepared by the Government of Sierra Leone with Technical Assistance from the Millennium Challenge Corporation of the United States of America, for the Development of a Millennium Challenge Compact DECEMBER 2013 i Table of Contents LIST OF TABLES 8 LIST OF FIGURES 10 1 INTRODUCTION 22 2 ECONOMIC GROWTH: HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE AND OVERVIEW 24 2.1 Summary Poverty Profile 26 2.2 GDP Growth Performance 27 2.3 Agricultural Sector Analysis 29 2.3.1 Contribution to GDP 29 2.3.2 Rice Production 30 2.3.3 Comparative Country Analysis 31 2.4 Export and Trade Performance 32 2.4.1 Trade Balance 32 2.4.2 Export Performance (2001‐2011) 33 2.4.3 Composition of Exports 34 2.4.4 Comparative Analysis 35 2.5 Industrial Sector 35 2.5.1 Comparative Country Analysis 37 2.6 Service Sector 37 2.6.1 Tourism 38 2.6.2 Finance, Insurance and Real Estate 39 2.6.3 Comparative Analysis 39 2.7 Trends in Real GDP per Capita 39 2.7.1 Conclusion 40 -

UNDP & UNCDF DFS Ecosystem Assessment in Sierra Leone

Final Country Report UNDP & UNCDF DFS Ecosystem Assessment in Sierra Leone Date: May 2016 Prepared by DFS Ecosystem Assessment in Sierra Leone TABLE OF CONTENTS Abbreviations ............................................................................................................................ 3 Executive Summary ................................................................................................................... 4 1. Overview of Digital Financial Services ............................................................................. 7 1.1 Snapshot of digital financial services and delivery channels ..................................... 7 1.2 Key definitions............................................................................................................ 7 2. Introduction .................................................................................................................... 8 3. Sierra Leone Background ................................................................................................ 9 3.1 Sierra Leone as a fragile state .................................................................................... 9 3.2 Fragility and financial inclusion ................................................................................ 10 3.3 Macroeconomic situation ........................................................................................ 11 4. Overview of SL Financial sector..................................................................................... 14 4.1 Financial institutions -

World Bank Document

ReportNo. 4457-SL SierraLeone i FinancialSector Study Public Disclosure Authorized February8, 1984 West Africa Region ProgramsI, Division B FOR OFFICIALUSE ONLY Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Documentof the WorldBank Public Disclosure Authorized This document has a restricted distribution and may be used by recipients only in the performance of their official duties. Its contents may not otherwise be disclosedwithout World Bank authorization. Currency equivalents Year US$ per Leone 1977 .95310 1978 .9531 1979 .9637 1980 .944:1 1981 .8516 1982 .8113 1983 (October) .3984 Fiscal year July 1 - June 30 FOR OFFICIALUSE ONLY Table of Contents Page No. SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS ...... .... ......... ........... .. i I. THE ECONOMY ...........................................................1 A. Aggregate savings and investment .............. .......... 2 B. Domestic and international value of the Leone .......... 2 C. Balance of payments .................................... 5 D. Government finances ........ oo..... ............... .... 8 E. Industry ................... ........... ... .. 9 F. Agricultural production problems .o ................. 9 II. MAJOR ISSUES OF THE FINANCIAL SYSTEM ..... o............... 12 A. The Government's demand for credit ..................... 13 B. Excess liquidity in the financial system ............. o 14 C. The foreign exchange pipeline .. o........................ 18 D Interest rate policy ......... .. o.. ......... .. 0 .... 20 III. THE RURAL FINANCIAL SYSTEM ...................