2007-Journal 14Th Issue

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

YB DEC 06.Pmd

YUVA BHARATI DECEMBER 2006 YUVA BHARATI Vol. 34 No.5 A Vivekananda Kendra Publication VOICE OF YOUTH 02 Prarthana Founder Editor P.Parameswaran MANANEEYA EKNATHJI RANADE 09 This years Kendra Samachar Editor:SHRI P. PARAMESWARAN 11 The Special events of the year Editorial Office: 5, Singarachari Street 12 Vivekananda Kendra Institute of Culture Triplicane, Chennai - 600 005 Ph:(044) 28440042 16 Vivekananda Kendra Natural Resources Email:[email protected] 17 Rural Development Programmes in T.N Web: www.vkendra.org 18 Vivekananda Kendra Vidyalayas SingleCopy Rs. 7/- Annual Rs. 75/- 24 Other events of the Vidyalayas For 3 yrs: Rs. 200/- Life(20Yrs) Rs. 800/- 28 V.K. Rural Welfare Project, Khatkati (Plus Rs. 30/- for outstation 39 An Appeal Cheques) They alone live who live for others, the rest are more dead than alive. -- Swami Vivekananda This Yuva Bharati is being sent to all Patrons of Vivekananda Kendra as Vivekananda Kendra Samachar titled as PRARTHANA. All Patrons are requested to enroll themselves as Subscribers of Yuva Bharati and other magazines of the Kendra. YUVA BHARATI DECEMBER 2006 PRARTHANA (Thoughts on Prayer) he Kendra Prayer is the soul force behind every Kendra worker. It is chanted every day as a part of Sadhana with total surrender and Tdedication. The Divine inspiration and the spiritual energy that emanates from the prayer enable and equip the worker to carry on the allotted work all through his life without the least expectation of any reward in any form whatsoever. It is this cumulative strength of collective prayer that sustains the purity, ability and strength of the organisation. -

New Arrival in Academy Library

New Arrival in Academy Library SL Name of Books Authors Name 1 The Book of Five Rings Miyamoto Musashi 2 The Creator's Code Amy Wilkinson 3 Kanthapura Raja Rao 4 Gods, Kings and Slaves R. Venketesh 5 Untouchable Mulk Raj Anand 6 Heart of Darkness Joseph Conrad 7 Make Your Bed William H. Mcraven 8 Give and Take Adam Grant 9 The Guns of August Barbara Tuchman 10 The Craft of Intelligence Allen W. Dulles 11 Parties and Electoral Politics In Northeast India V. Bijukumar 12 The ISI of Pakistan : Faith, Unity, Discipline Hein G. Kiessling 13 China's India War Bertil Lintner 14 The China Pakistan Axis Andrew Small The Hard Thing About Hard Things : Builing A Business When There Are No 15 Easy Answers Ben Horowitz 16 Great Game East Bertil Lintner 17 Ashtanga Yoga John Scott 18 1962 : The war that wasn't Shiv Kunal Verma 19 Sins of Gods : Warriors of Dharma Dr. Chandraanshu 20 Legal And Professional Writing And Drafting In Plain Language Dr. K. R. Chandratre 21 Line on Fire Happymon Jacob 22 Mocktails : Recipe Book Vivian Miller 23 An End To Suffering: The Buddha In The World Pankaj Mishra 24 The Seventy Great Mysteries of The Ancient World Brian M. Fagan 25 Dragon on Our Doorstep Pravin Sawhney ,Ghazala 26 A Handful of Sesame Shrinivas Vaidya , MKarnoor 27 The Biology of Belief Bruce H. Lipton 28 Hkkjr % usg: ds ckn jkepUnz xqgk 29 Indian Polity : For Civil Services Examinations M Laxmikanth 30 India Super Goods : Change The Way You Eat Rujuta Diwekar 31 A Book For Government Officials To Master: Noting And Drafting M.K. -

(Public Section) Padma Awards Directory (1954-2009) Year-Wise List Sl

MINISTRY OF HOME AFFAIRS (Public Section) Padma Awards Directory (1954-2009) Year-Wise List Sl. Prefix First Name Last Name Award State Field Remarks 1954 1 Dr. Sarvapalli Radhakrishnan BR TN Public Affairs Expired 2 Shri Chakravarti Rajagopalachari BR TN Public Affairs Expired 3 Dr. Chandrasekhara Raman BR TN Science & Eng. Expired Venkata 4 Shri Nand Lal Bose PV WB Art Expired 5 Dr. Satyendra Nath Bose PV WB Litt. & Edu. 6 Dr. Zakir Hussain PV AP Public Affairs Expired 7 Shri B.G. Kher PV MAH Public Affairs Expired 8 Shri V.K. Krishna Menon PV KER Public Affairs Expired 9 Shri Jigme Dorji Wangchuk PV BHU Public Affairs 10 Dr. Homi Jehangir Bhabha PB MAH Science & Eng. Expired 11 Dr. Shanti Swarup Bhatnagar PB UP Science & Eng. Expired 12 Shri Mahadeva Iyer Ganapati PB OR Civil Service 13 Dr. J.C. Ghosh PB WB Science & Eng. Expired 14 Shri Maithilisharan Gupta PB UP Litt. & Edu. Expired 15 Shri Radha Krishan Gupta PB DEL Civil Service Expired 16 Shri R.R. Handa PB PUN Civil Service Expired 17 Shri Amar Nath Jha PB UP Litt. & Edu. Expired 18 Shri Malihabadi Josh PB DEL Litt. & Edu. 19 Dr. Ajudhia Nath Khosla PB DEL Science & Eng. Expired 20 Shri K.S. Krishnan PB TN Science & Eng. Expired 21 Shri Moulana Hussain Madni PB PUN Litt. & Edu. Ahmed 22 Shri V.L. Mehta PB GUJ Public Affairs Expired 23 Shri Vallathol Narayana Menon PB KER Litt. & Edu. Expired Wednesday, July 22, 2009 Page 1 of 133 Sl. Prefix First Name Last Name Award State Field Remarks 24 Dr. -

Dipika's Detailed 2020 Hindu Calendar Prem Namaste, Vanakkum, Jai Mata Di, Jai Shree Krsna, Jai Shree Raam We at Pray That You Are Well

Dipika©s Detailed 2020 Hindu Calendar Prem Namaste, Vanakkum, Jai Mata Di, Jai Shree Krsna, Jai Shree Raam We at www.dipika.org.za pray that you are well... Many thanks for remaining an awesome Hindu¼ Many have asked us to compile an article on the Hindu calendar for example what are the Festivals dates and Rahu kalam . *** Do note that SOME of the information given below for the festival dates is from the S.A.H.M.S. We don't take any responsibility for the information supplied by them. We ONLY have done this for Hindu uniformity within South Africa. Should you have any issues with their dates below please do contact them on 031 3091951 or email [email protected] ***. {Another point of note is when you see a * before a prayer date it means this is not in the general Hindu calendar that Hindus have in their homes. I have added these dates because these are equally important prayer dates that sadly seems to be ignored every year.} DO NOTE:- All times indicated below, associated with the start or end of a religious day are in 24-hour format. Firstly the Festival dates are the dates that a Hindu observes. This is quite self explanatory. For example for Shree Ganesh Chaturthi, we have a full explanation of this very important festival date on our website. Many ask what is this festival all about and how does one go about celebrating it. Hence this website is meant to make people from all cultures more aware of these important Hindu festival dates. -

Sweekar S P E CI a L P O I N T S O F (CSCS NEWSLETTER)

CANADA SABHA OF CHITRAPUR SARASWATS Sweekar S P E CI A L P O I N T S O F (CSCS NEWSLETTER) INTEREST: VOLUME 5, ISSUE 3 J U N E 2 0 1 1 Upcoming Satsang Important Dates Upcoming Satsang The next Satsang will be held at Vrinda Rao's residence in Dundas on Sunday August 7, 2011 at 11.30 am. The directions to the residence will be sent shortly. Please send your RSVP by July 31st to Vrinda Rao at 905-627-7521 (e-mail: vrin- I N S I D E [email protected]) or to Maya at 905-566-7908 (e-mail [email protected]). THIS ISSUE: Annual Math 2 Vantiga Important Dates in June and July Chitrapur 2 Saraswat Census Jun 3 Punyatithi at Shirali—H.H. Shrimat Pandurangashram Swamiji ANZ Sammelan 3 Jun 7 Vardhanti at Shirali- H.H. Shrimat Anandashram Swamiji Sannidhi Report Jun 8 Vardhanti at Mangalore-H.H. Shrimat Vamanashram Swamiji CHF Sponsor- 4 Sannidhi ship Appeal Jun 10 Vardhanti at Mallapur-H.H.Shrimat Shankarashram Swamiji Sannidhi SVBF Program 5 Jun 15 Khagrassa Chandragrahana Jun 15 Birthday of PP Parijnanashram Swamiji III Photos 6 July 15 Guru Purnima / Chaturmas Vrata Prarambha July 31 Shravana Masa Prarambha VOLUME 5, ISSUE 3 P A G E 2 Annual Math Vantiga Paying the annual Math vantiga is not mandatory. But it is a sacred duty of every bhanap who is gainfully employed. Math depends on the vantigas for sevas performed for daily, viniyogas and maintenance of all sacred samadhis and math facilities. -

E:\ANNUAL REPORT-2019.Pmd

ESTD-1949 (1949-2019) 70th Anniversary Day 17th April, 2019 Tinkonia Bagicha - 753001 1 HOMAGE TO CHIEF PATRON Late Narendra Kumar Mitra FOUNDER MEMBERS Late (Dr.) Haridas Gupta Late Satyanarayan Gupta Late Preety Mallik Smt. Ila Gupta REMEMBRANCE (OUR SENIOR ASSOCIATES) 1. Late Sushil Ch. Gupta 12. Late Subrata Gupta 2. Late Nirupama Mitra 13. Late Robin Kundu 3. Late Sovana Basu 14. Late Nemailal Bose 4. Late Nanibala Roy Choudhury 15. Late Pranab Kumar Mitra 5. Late Ram Chandra Kar 16. Late Jishnu Roy 6. Late Narendra Ch. Mohapatra 17. Late Amal Krishna Roy(Adv.) 7. Late Sarat Kumar Mitra 18. Late Tripty Mitra 8. Late Subodh Ch. Ghose 19. Late Surya Narayan Acharya 9. Late Sunil Kumar Sen 20. Late Tarun Kumar Mitra 10. Late Renendra Ku. Mitra 21. Late Debal Kumar Mitra 11. Late Sanat Ku. Mitra LIST OF THE PAST LIFE TIME DEDICATED AWARDEE YEAR NAME OF THE AWARDEE DESIGNATION 2009 SMT. ILA GUPTA FOUNDER MEMBER 2010 LATE PRITY MALLIK(POSTHUMOUS) FOUNDER MEMBER 2011 LATE SATYA NARAYAN GUPTA FOUNDER MEMBER 2011 LATE (DR.) HARIDAS GUPTA FOUNDER MEMBER 2 EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE OF THE LIBRARY President : Sri Prafulla Ch. Pattanayak Vice-President : Sri Tarak Nath Sur Secretary : Sri Sandip Kumar Mitra Treasurer : Sri Debraj Mitra MEMBERS 1. Sri Pratap Ch. Das 7. Sri Prasun Kumar Das 2. Sri Sunil Kumar Gupta 8. Smt. Anushree Dasgupta 3. Sri Shyamal Kumar Mitra 9. Sri Indranil Mitra 4. Sri Dilip Kumar Mitra 10. Smt. Barnali Ghosh 5. Smt. Tanushree Ghose 11. Sri Santanu Mitra 6. Sri Swapan Kumar Dasgupta 12. Sri Dipanjan Mitra LIST OF THE CHIEF GUEST WHO GRACED THE OCCASION IN THE PAST 1950 : Sri Lalit Kumar Das Gupta, Advocate 1951 : Sri Lingaraj Mishra, M.P. -

The Glories of the Month of Kartika

3ب&≥∂π∞¨∫∂≠ªØ¨¥∂µªØ∂≠*®πª∞≤® TThhee GGlloorriieess ooff tthhee mmoonntthh ooff KKaarrttiikkaa Kartika M aas, also know n as Damodara M aas is described in the scriptures as the best among months. ª®∫¥®´Ω𮪮ªπ®¿®¥Ø¿¨ª®µ¥®¥®ª∞Ω®∑π∞¿®µ≤®π®¥ ¥®ÆØ®≤®πª∞≤®¿∂∫ª®´Ω®ªª®ªØ®∞Ω®∞≤®´®∫∞Ω𮪮¥ Ω®µ®∫∑®ª∞µ®¥ªº≥®∫∞¥®∫®µ®¥≤®πª∞≤®Ø∑π∞¿®Ø ¨≤®´®∫∞ª∞ªØ∞µ®¥™®≤∫¨ªπ®µ®¥´Ω®π®≤®¥®¥® ¨ª¨∫®¥∫¨Ω®µ®¥¿®∫ªº≤®π∂ª∞™®±∞ª¨µ´π∞¿®Ø ∫®¥¨Ω®≥≥®©Ø®ª®¥¿®ª∞µ®ª®ªØ®¿®±®µ®´∞©Ø∞Ø .≠®≥≥∑≥®µª∫ ªØ¨∫®™π¨´3º≥®∫∞∞∫¥∂∫ª´¨®πª∂,¨ ∂≠®≥≥ ¥∂µªØ∫ *®πª∞≤®∞∫¥∂∫ª´¨®π ∂≠®≥≥∑≥®™¨∫∂≠∑∞≥Æπ∞¥®Æ¨ ,¿ ©¨≥∂Ω¨´ #Ω®π®≤® ∞∫ ¥∂∫ª ´¨®π ®µ´ ∂≠ ®≥≥ ´®¿∫ $≤®´®∫∞ ∞∫ ¥∂∫ª ´¨®π /®´¥® /ºπ®µ® 4ªª®π® *Ø®µ´® ! * ®πªª∞≤® ∂π ªØ¨ ≠¨∫ª∞Ω®≥ ∂≠ ∂≠≠¨π∞µÆ ≥®¥∑∫ ª∂ +∂π´ * π∫µ® ≥®∫ª∫ªØ¨¨µª∞π¨¥∂µªØ∂≠#®¥∂´®π® * ®πªª∞≤®∫ª®πª∞µÆ≠π∂¥ ªØ. ™ªªØ- ∂Ω æØ∞™ØÆ≥∂π∞≠∞¨∫* π∫µ®!∫∑®∫ª∞¥¨∂≠©¨∞µÆ ©∂ºµ´æ∞ªØπ∂∑¨∫©¿, ∂ªØ¨π8®∫Ø∂´®'. ©∫¨πΩ∞µÆΩ𮪮∞µ ªØ¨¥∂µªØ∂≠* ®πªª∞≤®∞∫Æ≥∂π∞≠∞¨´∞µªØ¨/ºπ®µ®∫' ) ∫2®ª¿®¿ºÆ®∞∫ªØ¨©¨∫ª∂≠¿ºÆ®∫®Æ¨∫®∫ªØ¨5¨´®∫®π¨ ªØ¨ ©¨∫ª ∂≠ ∫™π∞∑ªºπ¨∫ ®∫ &®µÆ® ∞∫ ªØ¨ ©¨∫ª ∂≠ π∞Ω¨π∫ ∫∂ *®πªª∞≤® ∞∫ ªØ¨ ©¨∫ª ∂≠ ¥∂µªØ∫ ªØ¨ ¥∂∫ª ´¨®π ª∂ +∂π´ *π∫µ® !2≤®µ´®#/ºπ®µ® 3ب Ω𮪮 ©¨Æ∞µ∫ ∂µ +ªØ . ™ª∂©¨π ®µ´ ∂µ¨ ¥®¿ ∂©∫¨πΩ¨ ªØ¨ ≠∂≥≥∂æ∞µÆ ≠∂π¨¥∂∫ª ®™ª∞Ω∞ª∞¨∫ ªØπ∂ºÆØ∂ºªªØ¨¨µª∞π¨¥∂µªØ∂≠* ®πªª∞≤®, )®∑®™Ø®µª∞µÆªØ¨Ø∂≥¿µ®¥¨∫∂≠ªØ¨+∂π´ 6 ∂π∫Ø∞∑* π∫µ®©¿∂≠≠¨π∞µÆÆب¨≥®¥∑∫ ≠≥∂æ¨π∫ ∞µ™¨µ∫¨ ≠∂∂´®µ´¨ª™ /𮙪∞™¨©π®Ø¥®™®π¿®™¨≥∞©®™¿ 6 ∂π∫Ø∞∑∂≠3º≥∫∞´¨Ω∞ & ∞Ω¨∞µ™Ø®π∞ª¿ /¨π≠∂π¥®º∫ª¨π∞ª∞¨∫ ´®¥∂´®π®®∫ª®≤®¥µ®¥®∫ª∂ªπ®¥´®¥∂´®π®®π™®µ®¥ µ∞ª¿®¥´®¥∂´®π®®≤®π∫∞∑®ªØ¨ª∫®ª¿®Ω𮪮º´∞ª®¥ ' 1(40 1 * 3(5 (+ 2 +78+9 (µ ªØ¨ ¥∂µªØ ∂≠ *®πªª∞≤® ∂µ¨ ∫Ø∂º≥´ ´®∞≥¿ æ∂π∫Ø∞∑ +∂π´ #®¥∂´®π® ®µ´ -

Sweekar S P E CI a L P O I N T S O F (CSCS NEWSLETTER)

CANADA SABHA OF CHITRAPUR SARASWATS Sweekar S P E CI A L P O I N T S O F (CSCS NEWSLETTER) INTEREST: VOLUME 5, ISSUE 9 DECEMBER 2011 Upcoming Satsang Upcoming Satsang Important Dates The next Satsang , First of 2012 will be held on Sunday January 15th at Chetan and Aparna Kumta's residence 1309 Cartmer Way, Milton, ON, L9T 6J9. Please contact Maya Kulkarni at 905-566-7908 (email:[email protected]) or Aparna Kumta at 905-876-2641 to partici- pate in the Satsang please RSVP by January 10, 2011. I N S I D E THIS ISSUE: Important Dates in November and December Annual Math 2 Vantiga Dec 10 Shri Datta Jayanti Punyatithi at Shirali H.H.Krishnashram Swamiji Shashti 3 Dec 18 Invitation Dec 19 Punyatithi at Shirali H.H.Keshavashram Swamiji CSERS– Appeal 4 Jan 14 Makara Sankramana/Tilgula Jan 25 Punyatithi at Mallapur-H.H. Shrimat Shankarashram Swamiji II Indian Saint 5 Photo 7 Stamp and First Day Covers The commemorative stamp and first day cover has been issued by Philatelic Bureau of India. We have requested a small number stamps and first day cover. To View the recently release stamp please visit the following website http://www.indiapost.gov.in/Netscape/Stamps2011.html#2 VOLUME 5, ISSUE 9 P A G E 2 Annual Math Vantiga Our regular Vantiga payers, please consider to mail your contributions for 2011-2012 by the end of January 2012 to Sabha Treasurer Shri Vinayak Shanbhag at 5372 Floral Hill Crescent, Mississauga, ON L5V 1V3.(Tel.905-286-1896 e-mail:[email protected]). -

The Vakatakas

CORPUS INSCRIPTIONUM INDICARUM VOL. V INSCRIPTIONS or THE VAKATAKAS ARCHAEOLOGICAL SURVEY OF INDIA CORPUS INSCRIPTIONUM INDICARUM VOL. V INSCRIPTIONS OF THE VAKATAKAS EDITED BY Vasudev Vishnu Mirashi, M.A., D.Litt* Hony Piofessor of Ancient Indian History & Culture University of Nagpur GOVERNMENT EPIGRAPHIST FOR INDIA OOTACAMUND 1963 Price: Rs. 40-00 ARCHAEOLOGICAL SURVEY OF INDIA PLATES PWNTED By THE MRECTOR; LETTERPRESS P WNTED AT THE JQB PREFACE after the of the publication Inscriptions of the Kalachun-Chedi Era (Corpus Inscrip- tionum Vol in I SOON Indicarum, IV) 1955, thought of preparing a corpus of the inscriptions of the Vakatakas for the Vakataka was the most in , dynasty glorious one the ancient history of where I the best Vidarbha, have spent part of my life, and I had already edited or re-edited more than half the its number of records I soon completed the work and was thinking of it getting published, when Shri A Ghosh, Director General of Archaeology, who then happened to be in Nagpur, came to know of it He offered to publish it as Volume V of the Corpus Inscriptionum Indicarum Series I was veiy glad to avail myself of the offer and submitted to the work the Archaeological Department in 1957 It was soon approved. The order for it was to the Press Ltd on the printing given Job (Private) , Kanpur, 7th 1958 to various July, Owing difficulties, the work of printing went on very slowly I am glad to find that it is now nearing completion the course of this I During work have received help from several persons, for which I have to record here my grateful thanks For the chapter on Architecture, Sculpture and I found Painting G Yazdam's Ajanta very useful I am grateful to the Department of of Archaeology, Government Andhra Pradesh, for permission to reproduce some plates from that work Dr B Ch Chhabra, Joint Director General of Archaeology, went through and my typescript made some important suggestions The Government Epigraphist for India rendered the necessary help in the preparation of the Skeleton Plates Shri V P. -

The Journal of the Music Academy Madras Devoted to the Advancement of the Science and Art of Music

The Journal of Music Academy Madras ISSN. 0970-3101 Publication by THE MUSIC ACADEMY MADRAS Sangita Sampradaya Pradarsini of Subbarama Dikshitar (Tamil) Part I, II & III each 150.00 Part – IV 50.00 Part – V 180.00 The Journal Sangita Sampradaya Pradarsini of Subbarama Dikshitar of (English) Volume – I 750.00 Volume – II 900.00 The Music Academy Madras Volume – III 900.00 Devoted to the Advancement of the Science and Art of Music Volume – IV 650.00 Volume – V 750.00 Vol. 89 2018 Appendix (A & B) Veena Seshannavin Uruppadigal (in Tamil) 250.00 ŸÊ„¢U fl‚ÊÁ◊ flÒ∑ȧá∆U Ÿ ÿÊÁªNÔUŒÿ ⁄UflÊÒ– Ragas of Sangita Saramrta – T.V. Subba Rao & ◊jQÊ— ÿòÊ ªÊÿÁãà ÃòÊ ÁÃDÊÁ◊ ŸÊ⁄UŒH Dr. S.R. Janakiraman (in English) 50.00 “I dwell not in Vaikunta, nor in the hearts of Yogins, not in the Sun; Lakshana Gitas – Dr. S.R. Janakiraman 50.00 (but) where my Bhaktas sing, there be I, Narada !” Narada Bhakti Sutra The Chaturdandi Prakasika of Venkatamakhin 50.00 (Sanskrit Text with supplement) E Krishna Iyer Centenary Issue 25.00 Professor Sambamoorthy, the Visionary Musicologist 150.00 By Brahma EDITOR Sriram V. Raga Lakshanangal – Dr. S.R. Janakiraman (in Tamil) Volume – I, II & III each 150.00 VOL. 89 – 2018 VOL. COMPUPRINT • 2811 6768 Published by N. Murali on behalf The Music Academy Madras at New No. 168, TTK Road, Royapettah, Chennai 600 014 and Printed by N. Subramanian at Sudarsan Graphics Offset Press, 14, Neelakanta Metha Street, T. Nagar, Chennai 600 014. Editor : V. Sriram. THE MUSIC ACADEMY MADRAS ISSN. -

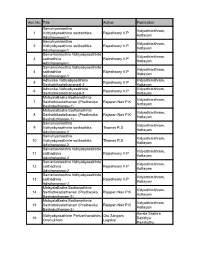

Library Stock.Pdf

Acc.No. Title Author Publication Samuhyashasthra Vidyarthimithram, 1 Vidhyabyasathinte saithadhika Rajeshwary V.P Kottayam Adisthanangal-1 Samuhyashasthra Vidyarthimithram, 2 Vidhyabyasathinte saithadhika Rajeshwary V.P Kottayam Adisthanangal-1 Samaniashasthra Vidhyabyasathinte Vidyarthimithram, 3 saithadhika Rajeshwary V.P Kottayam Adisthanangal-1 Samaniashasthra Vidhyabyasathinte Vidyarthimithram, 4 saithadhika Rajeshwary V.P Kottayam Adisthanangal-1 Adhunika Vidhyabyasathinte Vidyarthimithram, 5 Rajeshwary V.P Saithathikadisthanangal-2 Kottayam Adhunika Vidhyabyasathinte Vidyarthimithram, 6 Rajeshwary V.P Saithathikadisthanangal-2 Kottayam MalayalaBasha Bodhanathinte Vidyarthimithram, 7 Saithathikadisthanam (Pradhesika Rajapan Nair P.K Kottayam Bashabothanam-1) MalayalaBasha Bodhanathinte Vidyarthimithram, 8 Saithathikadisthanam (Pradhesika Rajapan Nair P.K Kottayam Bashabothanam-1) Samuhyashasthra Vidyarthimithram, 9 Vidhyabyasathinte saithadhika Thomas R.S Kottayam Adisthanangal-2 Samuhyashasthra Vidyarthimithram, 10 Vidhyabyasathinte saithadhika Thomas R.S Kottayam Adisthanangal-2 Samaniashasthra Vidhyabyasathinte Vidyarthimithram, 11 saithadhika Rajeshwary V.P Kottayam Adisthanangal-2 Samaniashasthra Vidhyabyasathinte Vidyarthimithram, 12 saithadhika Rajeshwary V.P Kottayam Adisthanangal-2 Samaniashasthra Vidhyabyasathinte Vidyarthimithram, 13 saithadhika Rajeshwary V.P Kottayam Adisthanangal-2 MalayalaBasha Bodhanathinte Vidyarthimithram, 14 Saithathikadisthanam (Pradhesika Rajapan Nair P.K Kottayam Bashabothanam-2) MalayalaBasha -

Vakataka Dynasty

Vakataka Dynasty The Satavahanas in peninsular India were succeeded by the Vakatakas (local power) who ruled the Deccan for more than two and a half centuries. The Vakatakas were the contemporaries of the Guptas in northern India. In the Puranas, the Vakatakas are referred to as the Vindhyakas. The Vakatakas belonged to the Vishnuvriddha gotra of the Brahmanas and performed numerous Vedic sacrifices. A large number of copperplate land grant charters issued by the Vakatakas to the Brahmans have helped in reconstructing their history. They were Brahmins and promoted Brahmanism, however, they also patronised Buddhism. Culturally, the Vakataka kingdom became a channel for transmitting Brahmanical ideas and social institutions to the south. The Vakatakas entered into matrimonial alliances with the Guptas, the Nagas of Padmavati, the Kadambas of Karnataka and the Vishnukundins of Andhra. The Vakatakas patronised art, culture and literature. Their legacy in terms of public works and monuments have made significant contributions to Indian culture. Under the patronage of the Vakataka king, Harisena, the rock-cut Buddhist Viharas and Chaityas of the Ajanta caves (World Heritage Site) were built. Ajanta cave numbers ⅩⅥ, ⅩⅦ, ⅩⅨ are the best examples of Vakataka excellence in the field of painting, in particular the painting titled Mahabhinishkramana. Vakataka kings, Pravarasena Ⅱ (author of the Setubandhakavya) and Sarvasena (author of Harivijaya) were exemplary poets in Prakrit. During their rule, Vaidharbhariti was a style developed in Sanskrit which was praised by poets of the likes of Kalidasa, Dandin and Banabhatta. Vakataka Origins • The Vakatakas were Brahmins. • Their origins are not clear with some claiming they are a northern family while others claim they originated in southern India.