An Exploration of Tracing and the Choreographic Process

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stillness in Time (1994)

Stillness in Time (1994) Transcription Notes: If you read through many of the old interviews done with Stuart you will know that he was highly inspired by Latin rhythm and time concepts. Although Jay liked this aspect of his playing, none of it really showed up on the !rst album. By the time the ‘The Return of the Space Cowboy’ was released, Stu’s Latin vibe was clearly showing through – possibly due to the arrival of new drummer Derrick McKenzie too. ‘Stillness in Time’ is by far one of the most technical Jamiroquai bass lines in terms of timing. The bass line is predominately based on a root-!fth movement which sometimes includes the 9th also. He then embellishes on top of this to "esh-out the bass part more - but this basic and common outline is always there. This is another of those tracks using the Warwick 4 string. The sound is not so de!ned and since it is an airy Latin/Samba groove, a lot of the notes are tied over to ring. The sound you are aiming to replicate (or get similar to) the record would be to boost the bass a little and add extra middle to your sound. Make sure it is smooth and punchy – muddy isn’t a bad sound for this track, particularly almost Dub like. You will be required to use the full extent of your technique on this track to nail it well. Try to consistently be a bar or two ahead of your playing (sight reading wise) so you are aware of what is approaching. -

Michael Bolton His Brandnewsinglecan 1Touch You...There? "Taken from the Forthcoming Columbia Release: Michael Bolton Greatest Hits 1985-1995

MAKING WAVES: Ad Sales For Specialist Formats... see page 8 LUME 12, ISSUE 35 SEPTEMBER 2, 1995 Blur Is Highest New Entry In Eurochart £2.95 DM8 FFR25 US$5 DFL8.50 At No.7 Page 19 Armatrading Meets Mandela PopKomm Bigger Than Ever, Say Industry Insiders by Jeff Clark -Meads In his keynote speech at assuredness on the German PopKomm, ThomasStein, music scene." COLOGNE -The German music chairmanoftheGerman Stein, who is also president industry and the annual trade label's group BPW, stated, "We of BMG Ariola in the German- fair it hosts are growing in in the recorded music industry speaking territories, went on size and confi- are proud ofto say that Germany has now dence together, PopKomm. joined the ranks of the world's according to the That is most importantrepertoire leadersof the becausePop- sources (for detailed story, see country's record POP Komm has page 5). companies. now estab- PopKomm,heldinthe PopKomm, KOMM. lished itself as gigantic Cologne Congress held in Cologne the world's Centre, this year attracted 600 The high point of BMG artist Joan Armatrading's current world tour was from August 17- Die Hesse fiir biggest music exhibiting companies and her meeting with Nelson Mandela. One of her "dreams came true" when 20, is being trade fair and occupied 180.000 square feet she met him while in Pretoria to promote her latest album What's Inside. toutedasthe Popmusik andit takes place of exhibition space-twice as During a one-to-one meeting at his residence, Mandela signed a copy of world'sbiggest Entertainment in Germany. -

Pop / Rock / Commercial Music Wed, 25 Aug 2021 21:09:33 +0000 Page 1

Pop / Rock / Commercial music www.redmoonrecords.com Artist Title ID Format Label Print Catalog N° Condition Price Note 10000 MANIACS The wishing chair 19160 1xLP Elektra Warner GER 960428-1 EX/EX 10,00 € RE 10CC Look hear? 1413 1xLP Warner USA BSK3442 EX+/VG 7,75 € PRO 10CC Live and let live 6546 2xLP Mercury USA SRM28600 EX/EX 18,00 € GF-CC Phonogram 10CC Good morning judge 8602 1x7" Mercury IT 6008025 VG/VG 2,60 € \Don't squeeze me like… Phonogram 10CC Bloody tourists 8975 1xLP Polydor USA PD-1-6161 EX/EX 7,75 € GF 10CC The original soundtrack 30074 1xLP Mercury Back to EU 0600753129586 M-/M- 15,00 € RE GF 180g black 13 ENGINES A blur to me now 1291 1xCD SBK rec. Capitol USA 7777962072 USED 8,00 € Original sticker attached on the cover 13 ENGINES Perpetual motion 6079 1xCD Atlantic EMI CAN 075678256929 USED 8,00 € machine 1910 FRUITGUM Simon says 2486 1xLP Buddah Helidon YU 6.23167AF EX-/VG+ 10,00 € Verty little woc COMPANY 1910 FRUITGUM Simon says-The best of 3541 1xCD Buddha BMG USA 886972424422 12,90 € COMPANY 1910 Fruitgum co. 2 CELLOS Live at Arena Zagreb 23685 1xDVD Masterworks Sony EU 0888837454193 10,90 € 2 UNLIMITED Edge of heaven (5 vers.) 7995 1xCDs Byte rec. EU 5411585558049 USED 3,00 € 2 UNLIMITED Wanna get up (4 vers.) 12897 1xCDs Byte rec. EU 5411585558001 USED 3,00 € 2K ***K the millennium (3 7873 1xCDs Blast first Mute EU 5016027601460 USED 3,10 € Sample copy tracks) 2PLAY So confused (5 tracks) 15229 1xCDs Sony EU NMI 674801 2 4,00 € Incl."Turn me on" 360 GRADI Ba ba bye (4 tracks) 6151 1xCDs Universal IT 156 762-2 -

A Nonverbal Language for Imagining and Learning: Dance Education in K–12 Curriculum Judith Lynne Hanna

A Nonverbal Language for Imagining and Learning: Dance Education in K–12 Curriculum Judith Lynne Hanna Curriculum theorists have provided a knowledge base concerning the common, narrow, in-depth focus for articles and instead aesthetics, agency, creativity, lived experience, transcendence, learn- address a panorama of issues that educators, dancers, and ing through the body, and the power of the arts to engender visions researchers have been raising, at least since my teacher training at of alternative possibilities in culture, politics, and the environment. the University of California–Los Angeles in the late 1950s. Underlying the discussion is the theoretical work of John However, these theoretical threads do not reveal the potential of Dewey (1934) and Eliot Eisner (2002), who have looked at the K–12 dance education. Research on nonverbal communication and arts broadly. They have established the significance of the expres- cognition, coupled with illustrative programs, provides key insights sion of agency, creativity, lived experience, transcendence, learn- into dance as a distinct performing art discipline and as a liberal ing through the body, and the power of the arts to engender applied art that fosters creative problem solving and the acquisition, visions of alternative possibilities in culture, politics, and the envi- reinforcement, and assessment of nondance knowledge. Synthesizing ronment. Dewey’s prolific writing and teaching at Teachers College of Columbia University prepared schools to offer dance and interpreting theory and research from different disciplines that for all children. He believed that children learn by doing—action is relevant to dance education, this article addresses cognition, emo- being the test of comprehension, and imagination the result of the tion, language, learning styles, assessment, and new research direc- mind blending the old and familiar to make it new in experience. -

THE CAMP of the SAINTS by Jean Raspail

THE CAMP OF THE SAINTS By Jean Raspail And when the thousand years are ended, Satan will be released from his prison, and will go forth and deceive the nations which are in the four corners of the earth, Gog and Magog, and will gather them together for the battle; the number of whom is as the sand of the sea. And they went up over the breadth of the earth and encompassed the camp of the saints, and the beloved city. —APOCALYPSE 20 My spirit turns more and more toward the West, toward the old heritage. There are, perhaps, some treasures to retrieve among its ruins … I don’t know. —LAWRENCE DURRELL As seen from the outside, the massive upheaval in Western society is approaching the limit beyond which it will become “meta-stable” and must collapse. —SOLZHENITSYN Translated by Norman Shapiro I HAD WANTED TO WRITE a lengthy preface to explain my position and show that this is no wild-eyed dream; that even if the specific action, symbolic as it is, may seem farfetched, the fact remains that we are inevitably heading for something of the sort. We need only glance at the awesome population figures predicted for the year 2000, i.e., twenty-eight years from now: seven billion people, only nine hundred million of whom will be white. But what good would it do? I should at least point out, though, that many of the texts I have put into my characters’ mouths or pens—editorials, speeches, pastoral letters, laws, news Originally published in French as Le Camp Des Saints, 1973 stories, statements of every description—are, in fact, authentic. -

The Catholic University of America

THE CATHOLIC UNIVERSITY OF AMERICA Sabbath / Sunday: Their spiritual Dimensions in the Light of Selected Jewish and Christian Discussions A DISSERTATION Submitted to the faculty of the School of Theology and Religious Studies Of The Catholic University of America In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree Doctor of Philosophy © Copyright All Rights Reserved By Jeanne Brennan Kamat Washington, D.C. 2013 Sabbath / Sunday: Their Spiritual Dimensions in the Light of Selected Jewish and Christian Discussions Jeanne Brennan Kamat, Ph.D. Christopher Begg, S.T.D., Ph.D. The Sabbath as the central commandment of the Law relates all of Judaism to God, to creation, to redemption, and to the final fulfillment of the promises in the eternal Sabbath of the end-time. However, early in the inception of Christianity, Sunday replaced the Sabbath as the day of worship for Christians. This dissertation is a study of the various aspects of the Sabbath in order to gain a deeper insight into Jesus’ relationship to the day and to understand the implications of his appropriation of the Sabbath to himself. Scholars have not looked significantly into Jesus and the Sabbath from the point of view of its meaning in Judaism. Rabbi Abraham Heschel gives insight into the Sabbath in his description of the day as a window into eternity bringing the presence of God to earth; Rabbi André Chouraqui contends that the Sabbath is the essence of life for Jews. According to S. Bacchiocchi when Christianity separated from Judaism by the second century, Sunday worship was established as an ecclesiastical institution. -

Song Name Artist

Sheet1 Song Name Artist Somethin' Hot The Afghan Whigs Crazy The Afghan Whigs Uptown Again The Afghan Whigs Sweet Son Of A Bitch The Afghan Whigs 66 The Afghan Whigs Cito Soleil The Afghan Whigs John The Baptist The Afghan Whigs The Slide Song The Afghan Whigs Neglekted The Afghan Whigs Omerta The Afghan Whigs The Vampire Lanois The Afghan Whigs Saor/Free/News from Nowhere Afro Celt Sound System Whirl-Y-Reel 1 Afro Celt Sound System Inion/Daughter Afro Celt Sound System Sure-As-Not/Sure-As-Knot Afro Celt Sound System Nu Cead Againn Dul Abhaile/We Cannot Go... Afro Celt Sound System Dark Moon, High Tide Afro Celt Sound System Whirl-Y-Reel 2 Afro Celt Sound System House Of The Ancestors Afro Celt Sound System Eistigh Liomsa Sealad/Listen To Me/Saor Reprise Afro Celt Sound System Amor Verdadero Afro-Cuban All Stars Alto Songo Afro-Cuban All Stars Habana del Este Afro-Cuban All Stars A Toda Cuba le Gusta Afro-Cuban All Stars Fiesta de la Rumba Afro-Cuban All Stars Los Sitio' Asere Afro-Cuban All Stars Pío Mentiroso Afro-Cuban All Stars Maria Caracoles Afro-Cuban All Stars Clasiqueando con Rubén Afro-Cuban All Stars Elube Chango Afro-Cuban All Stars Two of Us Aimee Mann & Michael Penn Tired of Being Alone Al Green Call Me (Come Back Home) Al Green I'm Still in Love With You Al Green Here I Am (Come and Take Me) Al Green Love and Happiness Al Green Let's Stay Together Al Green I Can't Get Next to You Al Green You Ought to Be With Me Al Green Look What You Done for Me Al Green Let's Get Married Al Green Livin' for You [*] Al Green Sha-La-La -

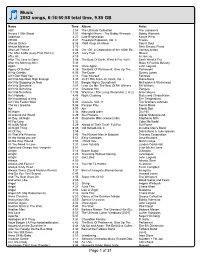

Tony's Itunes Library

Music 2053 songs, 6:16:50:58 total time, 9.85 GB Name Time Album Artist ABC 2:54 The Ultimate Collection The Jackson 5 Across 110th Street 3:51 Midnight Mover - The Bobby Womack ... Bobby Womack Addiction 4:27 Late Registration Kanye West AEIOU 8:41 Freestyle Explosion, Vol. 3 Freeze African Dance 6:08 1989 Keep On Movin' Soul II Soul African Mailman 3:10 Nina Simone Piano Afro Loft Theme 6:06 Om 100: A Celebration of the 100th Re... Various Artists The After 6 Mix (Juicy Fruit Part Ll) 3:25 Juicy Fruit Mtume After All 4:19 Al Jarreau After The Love Is Gone 3:58 The Best Of Earth, Wind & Fire Vol.II Earth Wind & Fire After the Morning After 5:33 Maze ft Frankie Beverly Again 5:02 Once Again John Legend Agony Of Defeet 4:28 The Best Of Parliament: Give Up The ... Parliament Ai No Corrida 6:26 The Dude Quincy Jones Ain't Gon' Beg You 4:14 Free Yourself Fantasia Ain't No Mountain High Enough 3:30 25 #1 Hits From 25 Years, Vol. I Diana Ross Ain't No Stopping Us Now 7:03 Boogie Nights Soundtrack McFadden & Whitehead Ain't No Sunshine 2:07 Lean On Me: The Best Of Bill Withers Bill Withers Ain't No Sunshine 3:44 Greatest Hits Dangelo Ain't No Sunshine 11:04 Wattstax - The Living Word (disc 2 of 2) Isaac Hayes Ain't Nobody 4:48 Night Clubbing Rufus and Chaka Kahn Ain't too proud to beg 2:32 The Temptations Ain't We Funkin' Now 5:36 Classics, Vol. -

Jamiroquai High Times Album Download Jamiroquai High Times Album Download

jamiroquai high times album download Jamiroquai high times album download. Completing the CAPTCHA proves you are a human and gives you temporary access to the web property. What can I do to prevent this in the future? If you are on a personal connection, like at home, you can run an anti-virus scan on your device to make sure it is not infected with malware. If you are at an office or shared network, you can ask the network administrator to run a scan across the network looking for misconfigured or infected devices. Another way to prevent getting this page in the future is to use Privacy Pass. You may need to download version 2.0 now from the Chrome Web Store. Cloudflare Ray ID: 67abc95c09bff162 • Your IP : 188.246.226.140 • Performance & security by Cloudflare. Jamiroquai - Discography (1993-2017) Artist : Jamiroquai Title : Discography Year Of Release : 1993-2017 Label : Sony, EMI, Mercury Genre : Funk/Acid Jazz/Electronic Quality : FLAC (*image + .cue,log) Total Time : 09:29:52 Total Size : 5,79 GB (+3%rec.) WebSite : Album Preview. 1993 - Emergency On Planet Earth - 55:26 ★●• 1993 1st Press •●★ Sony Soho Square|Sony Music Ent't (UK) Ltd. 01. When You Gonna Learn (Digeridoo) [0:03:50.40] 02. Too Young To Die [0:06:05.55] 03. Hooked Up [0:04:35.60] 04. If I Like It, I Do It [0:04:53.00] 05. Music Of The Mind [0:06:22.70] 06. Emergency On Planet Earth [0:04:05.12] 07. Whatever It Is, I Just Can't Stop [0:04:07.10] 08. -

Sselgnlq SMOH) Oniijnifli HOM A3>Pvsl )Tsnw Awau Uianiea} Gt ,Cinf Saaois Ve.Upunos Uouow O 09281 025 52 8 Tq Pampoid Aunqw >He.Upunos

$5.50 (U.S.), $6.50 (CAN.), £4.50 (U.K.) Seal Album IB?WCCVR ******** 3 -DIGIT 908 000 GGEE4EM740M099074# 002 0659 BI MAR 2396 1 03 Takes Off MONTY GREENLY 3740 ELM AVE APT A LONG BEACH, CA 90807 -3402 On Wings Of `Batman' Soundtrack SEE PAGE 8 THE INTERNATIONAL NEWSWEEKLY OF MUSäC, VIDEO AND HOME ENTERTAINMENT JULY 15, 1995 ADVERTISEMENTS h 'TO DESERVE YOU" BROADWAY L 5 R(.DUI.ID 3Y ARIF MARDIN HONKY-TONK BEAT: NASHVILLE'S LOWER wild. Tootsie's Back Room On Front Burner Dial BR5 -49 For Alternative Country BY CHET FLIPPO Tootsie's, and in turn, Lower Broad- BY JIM BESSMAN City. way. People still talk about the night Every week, Wednesdays through NASHVILLE -The joint is jumping, that Marianne Faithfull showed up to NASHVILLE -They're doing what Saturdays, from 10 p.m. to 2 p.m. and the room is packed. The Back Room duet with Garing on Hank Williams' countless guitar- toting dreamers with no breaks, the quintet -garbed at Tootsie's Orchid Lounge is vibrat- "I'm So Lonesome I Could Cry." Gar- have been doing in thrift store ing to a strange new sound that was ing started playing Tootsie's Back since the glory Western outfits actually last heard in this room some Room around the same time last sum- days of the old and named after Ryman Auditori- the consistently um: playing pure, flubbed phone hardcore country number in the music for tips at late "Hee Haw" one of the de- great Junior crepit bars bor- Samples' comic dering the for- car -salesman CARROLL GARING mer home of the routine -packs a Grand Ole Opry capacity crowd 40 years ago. -

Seite 1 Von 315 Musik

Musik East Of The Sun, West Of The Moon - A-HA 1 A-HA 1. Crying In The Rain (4:25) 8. Cold River (4:41) 2. Early Morning (2:59) 9. The Way We Talk (1:31) 3. I Call Your Name (4:54) 10. Rolling Thunder (5:43) 4. Slender Frame (3:42) 11. (Seemingly) Nonstop July (2:55) 5. East Of The Sun (4:48) 6. Sycamore Leaves (5:22) 7. Waiting For Her (4:49) Foot of the Mountain - A-HA 2 A-HA 1. Foot of the Mountain (Radio Edit) (3:44) 7. Nothing Is Keeping You Here (3:18) 1. The Bandstand (4:02) 8. Mother Nature Goes To Heaven (4:09) 2. Riding The Crest (4:17) 9. Sunny Mystery (3:31) 3. What There Is (3:43) 10. Start The Simulator (5:18) 4. Foot Of The Mountain (3:58) 5. Real Meaning (3:41) 6. Shadowside (4:55) The Singles 1984-2004 - A-HA 3 A-HA Train Of Thought (4:16) Take On Me (3:48) Stay On These Roads (4:47) Velvet (4:06) Cry Wolf (4:04) Dark Is The Night (3:47) Summer Moved On (4:05) Shapes That Go Together (4:14) The Living Daylights (4:14) Touchy (4:33) Ive Been Losing You (4:26) Lifelines (3:58) The Sun Always Shines On TV (4:43) Minor Earth Major Sky (4:02) Forever NOt Yours (4:04) Manhattan Skyline (4:18) Crying In The Rain (4:23) Move To Memphis (4:13) Worlds 4 Aaron Goldberg 7. -

Performance Art and the Prosthetic

Performance Art and the Prosthetic Suzie Gorodi 2014 Auckland University of Technology School of Art and Design A thesis submitted to Auckland University of Technology in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) For Martin 2 Table of Contents Attestation of Authorship ........................................................................................................................................ 5 Acknowledgements .................................................................................................................................................... 6 List of Figures ............................................................................................................................................................... 7 Appendicies 1 ............................................................................................................................................................. 10 Appendicies 2 ............................................................................................................................................................. 11 Abbreviation of Heidegger Texts ........................................................................................................................ 11 Abstract ........................................................................................................................................................................ 12 Preface .........................................................................................................................................................................